Death of a Christmas Tree

We’d bought the young spruce in a fit of environmental consciousness when we still lived in Cupertino, CA. and it served as our Christmas tree for several years. In 1973 it survived our move to Santa Barbara, carefully bolstered in the U-Haul truck so it wouldn’t get smushed. It put up with a year or so of Santa Barbara sunshine, had even come into the house one holiday season. But that year, 1975, the temperature spiked into the 80s just after Christmas and hot sun streamed into the house. I was too busy with holiday guests and activities to think about moving the tree outside into the shade, so it stayed inside far too long. By the time we disburdened it of its decorations and lugged it back outside, the damage was already done. Months later, when I could no longer bear to look at pathetic brown needles, I removed it from its pot. The roots were tightly bound around each other.

One received wisdom is that you buy a potted tree for the holidays, then plant it in your garden. But this is not realistic if the tree’s grown size will overpower existing plantings, or if its natural habitat is elsewhere. I found a curious example of this when a few decades later we moved to Mendocino. In the patch of native forest on our property I found two trees with silvery needles. A naturalist friend identified them as some kind of spruce, definitely not native. She told me the story of how they most likely got there. The original developer had been hauled into court for illegally logging the property to create a “view development” and was ordered to replant. She speculated that he picked up a job lot of leftover Christmas trees to fulfill this requirement. Our two spruces, crowded out by redwood and Douglas fir, did not survive much longer.

So what to do about a Christmas tree? Over the years we’ve tried various approaches. We’ve gone to cut-your-own tree farms. But sawing into a young tree felt like committing murder. We’ve bought a cut tree from a lot and kept it outside in a tub of water for as long as possible. Even so, it would be shedding needles even before it came into the house. It would have been been cut weeks before, and shipped hundreds of miles from where it was grown. We’ve thinned out young firs from our own property. But they’ve been spindly little things, too likely to topple.

For the past couple of years, we’ve not bothered with a tree at all. I’ll maybe clip some low-hanging conifer branches to make a big arrangement in a bowl on the dresser or a wreath for the door. But that’s about it. I like my trees living. Like this baby Grand Fir that workers clearing a drainage channel a few weeks ago rescued from an overgrown coyote bush and saved for me.

Looking back at a life

The cover image is a detail from the watercolor painting “Under the Fog” by Mendocino Coast artist Karen Bowers.

So far this blog has been a form of memoir: small stories and reflections about some aspect of my history. Today I break that pattern to tell you about another aspect of my writing life, poetry. I’m excited to announce that my latest collection of poems, Horizon Line, will be published next April by Main Street Rag Publishing Co. The publisher has set up a handsome webpage where you can place pre-publication orders at a substantial discount from the $14 list price.

Horizon Line is also a kind of memoir. The title poem sets the theme of the book: “To limn a life in perspective …” From my house on the Mendocino Coast in Northern California, I watch the sea fog move in and out, changing as it does the viewer’s perception of where the horizon is. I use this variability as a metaphor for what it’s like to look back on my life. Here’s the poem in full:

Horizon Line

To limn a life in perspective

the artist first defines

a horizon line eye level to the viewer.

From my hill of years the horizon

is fluid as in watery, but also

as in unpredictable.

On the sea’s face a wall of fog

moves in and out like histories

remembered and forgotten.

Sometimes silver striates the sea

with such a glitter of insight

I am bedazzled and cannot look.

Sometimes fogbank and ocean

merge with such blue-gray unity

it seems the horizon rises

so that I stand on the shore

dwarfed by a surf of knowledge

that pounds at my ignorance.

Sometimes the sea becomes invisible

the white air a questioning emptiness

a finger-touch of damp against the cheek.

Indigo Moor, Poet Laureate of Sacramento Emeritus, said this about the collection:

In her new poetry collection, Horizon Line, Maureen Eppstein takes an imagistic look at the systole and diastole of the immigrant experience. Divided into four chambers, Horizon Line presents a New Zealand eye’s view of the American experience, from the landing on these shores, through the struggle for spirituality, and, finally, to the unerring clarity of the clearing at the end of the path.

Like a retrospective exhibition of an artist’s work, I see this book as a summing up of my spiritual and artistic journey. I would be honored to have you as one of my readers. Again, here’s the link for ordering Horizon Line:

The persistence of hope

Reading through letters I wrote to my parents in early 1973, I am struck by how much writing I was doing, in spite of all the other stuff going on in my life.

January 10, 1973

(Having been laid off in an economic downturn, my husband was job-hunting.) Nothing new regarding our plans – I wish the thing was settled soon. …

I have been hectically busy for the past month or so. … This week I have been working on an outline of my novel, and polishing up several chapters for a grant-in-aid that is being offered by the San Francisco Foundation. Don’t have much chance of winning it, but less if I don’t enter! … I have a huge pile of papers to grade (my freelance job as a reader for a local high school), for which I shall have to read the textbook first; another reference book on the Indian rock drawings we visited at Tulelake (for an article); and a story to finish on the disposal of Christmas trees for which I have a go-ahead from a local magazine.

February 12, 1973

February 12, 1973

Finished today a short story based on our experience of buying a baby Christmas tree this year. We were going to give it to a park, but the kids wanted to keep it. The kids like the story, so I hope the women’s magazines will.

March 3, 1973

Our own plans are getting more finalized. Tony will be commuting between here and Santa Barbara for a few months … and then we expect to move south when the kids finish school in June. … but at least now I know what sort of time scale I have for finishing up projects here. I am currently working on a big story about the influx of older, traditionally brought up housewives into the women’s movement, and have several other ideas on file that I will need to get material for before we leave, As usual, every new idea spins off into several new stories, and I can’t possibly find time to do them all.

March 22, 1973

Tony leaves for Santa Barbara Monday, and I am going to drive the kids down later in the week for a long weekend of looking around and getting our bearings. … In the meantime I have a huge pile of students’ field trip reports sitting on my desk … and then back to the draft of a story that could be the most important thing that has happened to me career-wise. I have an invitation to submit to Harpers Magazine (and that is the top) a story on the women’s movement. My thesis is that the rapidly increasing numbers of middle-aged, middle-class housewives being attracted to the movement is having a significant effect on the direction of feminist politics. I have been very involved with the setting up of a chapter of National Women’s Political Caucus here, and have also got many insights from the Department of Continuing Education for Women at Foothill College, which is very active in encouraging frustrated housewives to get back into the mainstream of life.

Of course a go-ahead doesn’t mean the story is sold. I think I have learned a lot about this since last year, when I was so crushed that the famous publishing house which wanted to see my novel sent it back again. But still it’s exciting to have it even considered.

Where are they now, all these articles and stories I worked so hard on? Gone. Never published. Not even copies crammed into my old black filing cabinet. I must have thrown them out in a fit of tidiness, or more likely despair. I can’t even find the kind, hand-written rejection letter from the editor of the famous publishing house, which I know I kept for years. All that’s left is the memory of how hopefully we writers begin new projects again and again and again.

Sitting down with lions

In many cultures, humans see themselves as siblings to other living beings. In Aotearoa New Zealand, where I grew up, the Māori people recognize landforms such as mountains and rivers as their relatives. Even in Western Judeo-Christian societies, where humans are believed to have been make in God’s likeness and to have dominion over all creatures (Genesis 1:26), people with beloved domestic pets may discover that their relationship is closer to that of peers than of master and subject.

My own views, which come closer to those of scientific pantheism, had a formative moment one summer day in the early 1970s, when my friend Judi and I took our children to the Oakland Zoo. I tell about it in a letter to my parents:

A lion cub recently born at the Denver Zoo. Image from the Denver Post.

The biggest thrill of the day, I got to cuddle a lion cub. Little 7 week-old roly-polies, they had been separated from their mother – I gather the father was threatening to harm them in the cramped quarters of the adult lions. We happened to be there at bottle time, and the keepers brought them out to a low platform in the children’s zoo. They obviously need lots of affection. I was sitting on the platform, and one of them just crawled into my lap, like a kitten or a puppy.

I will remember always the roughness of the cub’s fur under my hand, the warmth of his tiny body, the loudness of his purr, the overwhelming sense of awe that this wild creature trusted me. Here’s a poem about the incident:

The Lion Cub

In the dusty heat of the zoo

a lion roars.

I conjure a dream of Africa

an endless veldt

an alien majesty

concealed in yellow grass.

At the petting zoo

three lion cubs

explore a patch of dirt.

I sit.

One crawls into my lap

nuzzles my hand.

Under thick baby fur

muscles ripple, relax

curl up for a nap.

Wide-eyed, the children watch

and touch.

Distance evaporates.

We are earth family

connected deep in time

in mother love.

Making acquaintance with snakes

Growing up in Aotearoa New Zealand, a country with no native snakes, I never learned the phobia many people have about these creatures. Since moving to California I’ve learned to keep rattlesnakes at a respectful distance, but can only listen, fascinated, as friends tell stories of the poisonous slithery ones of their childhoods.

Our family had a fine introduction to the harmless garter snake in 1972, when we went camping at Big Sur during spring break. I tell about it in a letter to parents:

27 April 1972

We had a lovely trip to Big sur. The coastline there is really spectacular – a romantic tumble of cliffs and waves, with the highway carved out of the side of the cliff. …The campground is back in the valley of the Big Sur River, a lush, green, woodsy place, with the river bronze-gold over its boulders. We camped right on the edge of the river, and as you can imagine the kids [our two plus their friend Mark, ages nine, eight and seven] had a ball messing about in the water. … Lots of wildlife for us to observe. One day, coming back from the beach at the mouth of the river, we met a man who had caught a huge garter snake, and was taking it home to his daughter, who collected reptiles. Both he and the snake were very obliging about letting the kids play with it and handle it, and it was a very contemplative, envious trio that walked back across the river meadow where he had found it. It’s interesting to observe the effect of the nature programs they have attended on these kids. A lot of emphasis is put on the phobias and misconceptions that many people have about snakes. The children learn how to watch out for rattlesnakes, but they also learn to value the many other useful and beautiful snakes we have here. Following their example, I even held a snake for the first time, a baby Santa Cruz garter snake that Tony had found by the campsite. A pretty little thing, striped lengthwise yellow and black, and warm and wriggly in the hand.

We have had other snakes in our lives. In Santa Barbara, where we lived in the late 1970s, a huge king snake took up residence in our garden. Since king snakes eat rattlers, we were happy to make it welcome. Less welcome were the pair of caged garters one of our sons and a visiting friend brought back in guilty triumph from a local pet shop. My son assured me that he would be responsible for feeding and taking care of them. Yeah, right! Fortunately, both snakes managed to escape within a few days.

Here on the Mendocino Coast I often see garter snakes, either on a walking trail or in the garden. I have learned to live with the cycles of nature that make them both predator and prey. Here’s a poem about that:

Learning Detachment

Mirror black, raven on the wall

lifts limp coils of garter snake

its skin striped red and brown

in intricate pattern like a carpet

loomed in some ancient sunlit place

maybe the same snake I saw

near where a tree frog

shiny as sun on a wet spring leaf

leaped into shadow

sadness for lost beauty

rises and dissipates

the snake has eaten

the raven eats

How we came to live in Mendocino

We’d never been camping before as a family when, in the summer of 1971, Tony and I decided to take our children, then eight and five, on a short trip to explore some of the northern part of California. On our return, I wrote an ecstatic letter to my parents:

The beach at Russian Gulch State Park, looking under the bridge to the sea. Image by David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons.

25 August 1971

I guess I haven’t told you about our camping trip. We had a marvellous time, and are really sold on camping. We hired a 9×9 tent, and bought a pup tent for the boys, a propane stove and lantern, and a very nice ice box, so we were pretty well set up, and the state park campgrounds are really very civilised, with your own picnic table and food cupboard, and running water, bathrooms and showers not too far way. We spent five nights at Russian Gulch, which is on the Mendocino coast, about 200 miles north of here. This really is a delightful spot. The sea coast here is very rugged, with steep cliffs and caves and tumbled rocks, and grassy meadows on the headlands, with pine and redwood forests behind. The gulch is made by a lush little creek that flows into a tiny cove, making a perfect beach for the children, and the campsites are straggled along the edge of the creek, sheltered from the sea wind, and with a view of redwoods high above you. The weather was beautiful – only a trace of fog a few mornings, and it can be thick all the time. The children got very used to going for long walks, and we also spent a lot of time just sitting and unwinding and watching the wildlife – lots of jays, rabbits, chipmunks and garter snakes. The anchovies were running in the cove, so thick they were being hauled in by waders with nets, and of course they attracted the bigger fish. We were sitting on the beach one afternoon when a group of scuba divers came along with a huge catch, and offered us some, so we had fresh cod for supper.

After describing our impressions of Mendocino village – “splendid weather-beaten old buildings, many of them fine examples of carpenter Gothic, very similar to New Zealand colonial period architecture” – the letter continues:

From Russian Gulch we went on up the coast highway then inland to the Humboldt Redwoods. These are very lovely and impressive, but I think our hearts were still at Russian Gulch.

Here’s where the story takes a mythic turn. Here’s how I tell it now:

Once upon a summer afternoon a man and a woman sat on a beach. As the couple sat and gazed, a young man emerged from the sea. He was beautiful, with golden hair that hung to his shoulders and a body that had known good exercise. From each of his hands hung a fish, whose scales shone wet and silvery.

The woman called out, “Nice catch!” to the fisherman as he passed.

He paused. “Would you like one?”

The woman’s fingers flew to her blushing face. “Oh no, no, I didn’t mean …”

The fisherman lingered. “Please. I have more than I need.” He held out one of the fish.

The man sitting with the woman rose slowly to his feet. The fisherman placed the fish in his out-stretched hands. The man bowed his head and murmured his thanks. That evening, the man and the woman cooked the fish over their campfire and ate its sweet flesh.

After the man and woman returned to the city, every now and then they would feel a tug, as if they were being played on an invisible line. They would say to each other, “We need to go back to that place.” So they would rent a house on the coast for a week or two. The sea sang to them, and each evening a golden light would seep like an enchantment across the drowsy headlands. When their time was up, they would return sadly to the city.

In this way thirty years passed. Each year the tugs grew stronger, the city more and more unbearable. At last they could resist no longer. They left the city. In a house close to where they had eaten the fish, where the scent of the sea came to them, they quietly lived out their days.

Gifts of an old tree

Ripe apricots on a tree. Image from Nature & Garden.

The Cupertino CA neighborhood where I lived in the early 1970s was developed about 1962 on the site of an old apricot orchard, the trees probably planted before the post-WWII boom of the 1950s transformed the orchard-covered Santa Clara Valley into Silicon Valley. The developers had left an apricot tree on each lot. Gnarled and picturesque, they provided welcome shade on hot summer days, and a harvest of apricots for those who loved them. Letters to my parents from two different years offer a glimpse of harvest time:

26 June, 1970

… Meanwhile, the apricots are getting ripe. We have started picking, and they are delicious. Several neighbours with trees (this used to be an orchard) don’t like them too much, so those of us that do are planning to get together and pick for drying. You have to have 65 lbs. of fresh fruit to fill a tray, and a local orchard will sulphur and dry them for us for $30 a tray – pretty cheap dried apricots!

Apricots drying in the sun at the Curry family orchard in San Jose, date unknown. Standing are Douglas and Howard Curry. Image from Lisa Prince Newman’s blog, For the Love of Apricots.

I still remember the fun we had at that orchard in Los Altos Hills. It had a long, open-sided shed with a work table running down the center. My friend Judi and I and other women of the neighborhood stood at the table, cutting or breaking open pound after pound of golden, honey-scented fruit and laying them on the drying trays. Beyond the shed we could see a stretch of bare earth where the big wooden trays of fruit lay open to the sun. About ten days later we returned and were presented with our now-dried fruit, shriveled, somewhat brown, but delicious. A year later:

26 July, 1971

I have also been busy coping with the apricot crop. Our poor old tree has really taken a beating this year. We lost a third of it in the spring with fire blight, and then came home one afternoon when they were just about ripe to find a huge branch crashed to the ground. The poor thing is just dying of old age, and we shouldn’t have let it carry so much fruit. I managed to salvage about 70 lbs. from the broken branch, which we took to a commercial orchard to be dried. They turned out very well this year. They shrink, of course, to a fifth of their weight, but 13 lbs. of dried apricots is a fair quantity. I have also bottled quite a lot, and made jam, and then we had a bright notion of drying another 30 lbs. at home and making wine with them. This is Tony’s project, and he has been having a great time with it. We came home the other night (after eating out with friends) to find that the yeast was working so well in one jar that it had blown the top off, and there was gicky apricot pulp all over the counter!

Decades later, when we finally opened a forgotten bottle of that wine, it was vinegar. Oh well … By then we were no longer living in Cupertino, so I don’t know how much longer that kind old tree lived. I hope its new humans gave it a dignified end.

The way we see ourselves (and others)

Some years ago, when I was still in the workforce, I was rebuked at a performance evaluation for “not putting [myself] forward enough.” Startled, I explained to my boss that in the New Zealand culture in which I grew up, to boast about one’s accomplishments was considered very bad form. Modesty, on the other hand, was praiseworthy. I still think this is true. But I’ve come to realize that New Zealanders had, and probably still have, a contradictory notion: a self-perception of being more self-reliant, more able to come up with creative solutions to problems than people of other nations, such as Americans. This trait, we told ourselves, arose from necessity. Lacking an industrial base, and being so far away from industrial centers, New Zealanders had to import manufactured goods at high cost or make do and mend what we had. Everyone I knew grew their own vegetables. Women sewed and knitted. Car owners kept their vehicles for as long as possible. Frugality was a virtue.

I saw evidence of this sense of superiority to Americans in an exchange of letters with my mother in the early 1970s. I told my parents about a landscaping project Tony and I were working on at the house we’d recently purchased:

April 12, 1971

We turned bricklayers this weekend, and have now laid half of the front courtyard in red brick, basket weave pattern. It is looking beautiful—we are really very proud of ourselves, and it wasn’t as difficult as we expected. We used a dry mortar method, laying a base of sand mixed with cement, and tamping in a richer cement/sand mixture between the bricks. The most tedious part was washing off each brick and smoothing the mortar with a fine spray of water. Then twelve hours later you just slosh the lot down really thoroughly and leave it to set. Needless to say, we are both very fit these days. Apart from a patch of sunburn on my shoulders, I am feeling no ill effects at all today.

In her next letter, Mum must have made some comment on how impressive we must appear to our neighbors, doing all this work ourselves. And how typical of New Zealanders. I responded:

May 2, 1971

New Zealanders don’t have the monopoly on do-it-yourself, you know! You should see the crowds at the handyman-type shops every weekend here.

I continued with an anecdote that shed a less than favorable light on the prejudices of some other Kiwi immigrants:

We were a little amused at another N.Z. couple we know, who have this thing about N.Z. characteristics. We had invited them to dinner, & I tried to give [our friend] directions—after all, Cupertino’s house numbering system is completely random, & I thought they might at least want to know what freeway exit to take. But she pooh-poohed the whole thing—it was “terribly American” to give directions—if they couldn’t find their way by map they weren’t self-respecting N.Zers! As it turned out, they had (inefficiently) double-booked on engagements, & couldn’t come …

Reading this exchange again after so many years, I recognize the beginnings of a shift in allegiance. I was no longer blindly loyal to the sometimes insular attitudes of my birth country. I was learning to question assumptions and beliefs about any group of people. I was learning that being an immigrant is complicated.

The Easter Bunny mystery

How could my husband and I be so mean as to deny our kids the Easter Bunny? I frowned as I reread the letter to my parents stashed in my old black filing cabinet.

12 April 1971

The kids are back at school today after their week of Easter vacation. The weather has been so beautiful and spring-like. This is something I couldn’t really understand until I came to the northern hemisphere—the significance of Easter as a spring festival—the death and rebirth of the god that is an important part of almost every religion there has ever been. Here a big thing at Easter is the Easter Bunny, who is alleged to bring baskets of candy eggs and goodies to kids on Sunday morning. This Tony and I just can’t go along with—somewhat to the kids’ disappointment, I think, though we do buy them a fancy Easter egg, and of course we have the fun and mess of dyeing hard-boiled eggs and hiding them in the garden for an egg hunt. I did allow Simon to share our pet rabbit at school one morning. Bun-Bun was less than enthusiastic about the whole project, but the children were ecstatic.

Part of the reason for our rejection of the Easter Bunny was that Tony and I grew up in New Zealand, where rabbits were despised as pests. Brought by early settlers to a place with no natural predators, their population quickly reached plague proportions, causing major erosion problems. We did have Easter eggs, but given that we celebrated the festival in the Southern Hemisphere autumn, they had no significance other than as a source of sugar and chocolate. Even living in California, we couldn’t see any connection between rabbits and the Christian celebration of the Resurrection. I decided this week to look into the question. I quickly found myself down a fascinating rabbit hole of customs, beliefs, and theories, many of them contradictory.

How the Easter Bunny came to the U.S. seems pretty clear. According to several sources, the creature first arrived in America in the 1700s with German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania and transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws” who brought colored eggs to good children at Easter. As the custom spread across the U.S. the hare somehow transformed itself into the more familiar rabbit and its Easter morning deliveries expanded to include chocolate and other types of candy and gifts.

The hare’s (or rabbit’s) connection with Christianity are more complicated. For the first few centuries, the Christian festival coincided with the Jewish Passover, which is when the historical events surrounding Jesus’s death occurred. Though the Christian calendar has since been modified, both festivals are still close to each other in spring. Both are based on a lunar calendar; the date of Easter was defined in 325 CE by the Council of Nicaea as the first Sunday after the first Full Moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox. In Anglo-Saxon regions of Northern Europe, the Christian festival seems to have merged with a pre-existing equinox festival honoring Eostre, the goddess of spring, and Christians continued to use the name of the goddess to designate the season. Since hares and rabbits give birth to large litters in early spring, they have long been recognized as symbols of the rising fertility of the earth at the vernal equinox.

No, no, no, say some Catholic writers. The Easter Bunny has Christian origins. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that the hare could conceive again while pregnant, thus shortening the time between litters and delivering more offspring during a breeding season. Later Greek writers such as Pliny and Plutarch expounded the notion that hares (and rabbits, by association) were hermaphrodite, and thus could self-impregnate and reproduce as virgins. During the medieval period, hares and rabbits began appearing in illuminated manuscripts and paintings depicting the Virgin Mary, serving as an allegorical illustration of her virginity.

Two pregnancies at once? Intrigued, I veer into another passageway of my research rabbit warren. It turns out that, as the Smithsonian Magazine put it, “Aristotle got it right: the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) can get pregnant while it’s pregnant.” In 2010, scientists of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, Germany, led by Dr. Kathleen Roellig, published the results of their study. Using selective breeding and high-resolution ultrasonography, they showed that a male hare can fertilize a female during late pregnancy. The resulting embryos will develop around four days before delivery of the first pregnancy. To quote from the Smithsonian article: “The embryos don’t have any place to go at that time, however, since the uterus is occupied by the embryos’ older brothers and sisters. So the embryos hang out in the oviduct, rather like when you wait in your car for a parking space to open up. Once the uterus is free, the embryos move in.”

My head is spinning. I think I need chocolate.

The way we learn to belong

Once more we are at that seasonal turn familiar in California history: after a winter of great rains, floods and mudslides, the promise of an extraordinary blaze of color as wildflowers burst into bloom. My first experience of this magical transition was in 1969, my second spring in this new country. I describe it in letters to parents:

Feb. 28, 1969

It has actually stopped raining for the past hour. Another shower on the way, of course, but such a respite to see the sun. We have been averaging one sunny day a week for the past two months, and the general situation is already critical. We are not doing too badly in the Santa Clara Valley. All the creeks are contained by reservoirs up in the hills, and although the largest one, Anderson, is spilling over the top and flooding parts of east-side San José, the others are still holding their own. Fortunately the weather-man had predicted a respite for the next four or five days, i.e., drizzle instead of a deluge, and the authorities are hoping to get enough water away through the sluices of the other six dams during this time to make room for next week’s storms. Where we live is on relatively high ground anyway, so it is unlikely that we would be affected. The really big headache though is Central Valley, which drains the whole of the Sierra Nevada range. The Sacramento-San Joachim delta has flooded twice already in the past two months, and the river levels are still dangerously high. But in the high Sierra the snow fall is already twice the annual average, and we are only one third through the rainy season. Sooner or later that stuff is going to thaw, and if there is a warm rain up there, the effect will be sudden and disastrous. Meanwhile, it is still raining, with violent storms rolling in from the Pacific with tedious regularity. For some vast meteorological reason, the storm belt has swung further south than normal this year—so we are getting what Alaska usually gets. (They say it’s a mild winter in Alaska this year!)

A field of mixed wildflowers: Arroyo Lupine, Baby Blue-eyes, Purple Owls Clover and Tidy-tips. Image from Mother Nature’s Backyard.

And a few weeks later:

April 14, 1969

[After a visit to the Lick Observatory on Mt. Hamilton] We decided to see what it was like on the other side of the mountain. We found ourselves in a charming little valley, the San Antonio, which we followed back to Livermore and the freeway home. The land in this part is lightly wooded, and very sparsely populated—we saw a few ranch houses, occasional small herds of cattle, the odd horseman and dog, and that’s all. And at this time of year, the earth between the trees is covered with fresh grass, so scattered and strewn with wildflowers that it looks like some magic carpet.

I think it is one of the most wonderful sights I have ever seen. Great swathes of colour, of every shade. One they call Sunshine, or Goldfields, a tiny daisy-like flower, brilliant yellow. It grows only a few inches high, but in such profusion that, as its name implies, it makes a great field of colour. And on the slopes of Mt. Hamilton we thought for a while the snow was still lying, there were such patches of a snowy white flower. But other colours too, pinks and blues right through to the purples and reds. And down in the lower valleys, the California poppy, a brilliant orange. …I love these flowers so much.

An interviewer recently asked me what moved me toward writing about nature. I replied that as an immigrant, learning about the land was a big part of learning to belong to my adopted country. I’ve found this be particularly true when I moved from the Bay Area to the Mendocino coast. I’ll always be grateful to Dr. Teresa Sholars, whose College of the Redwoods wildflower identification class gave me the names of beloved beauties. Here’s a poem about them:

California Wildflowers

It seems a simple joy

to greet the flowers by name

Tidy Tips, Goldfields, Blue-Eyed Grass,

Crane’s Bill and Cream Cup,

Sticky Monkey Flower,

Mule’s Ears, Owl’s Clover,

Sun Cups glossy by the path,

Milkmaids in shade,

Lupine and Poppy on the slope,

but to the immigrant who after 40 years

still speaks with foreign intonation,

these are pet-names for familiars

precious as friends,

who speak in a language without words

of soils: clay and serpentine,

of rains and drought,

the way the lineaments of the land

impress themselves,

the way we learn to belong.

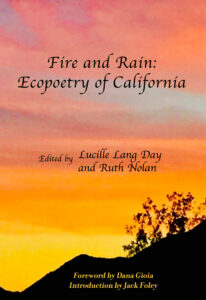

In a couple of days I’m off to Portland, OR for the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) conference. I was invited to be part of a group representing Scarlet Tanager Books, publisher of the anthology Fire & Rain: Ecopoetry of California, in which I have several poems. We’re hosting a reception at the conference, and doing a reading at a neighboring bookstore. Being recognized as an “ecopoet of California” makes me feel that, after what is now 52 years, this beautiful state is home. Enjoy this season’s flowers.