Author Archive

Political women in the 1970s

In early 1972 I had a note from the women’s editor of my New Zealand newspaper requesting pieces on how the women’s liberation movement had changed the role of women in politics. “Surely,” she said, “women over there do more than make tea for the candidates.” My response was a two-part series. First, the attitudes and roles of party workers in my county, now more widely known at Silicon Valley. In my next post, I’ll share a profile of a woman political candidate.

Women in Politics Part I:

Party workers reflect range of attitudes

Santa Clara County, CA, 1972

The grey-haired woman in the Republican campaign trailer sniffed contemptuously. “Women’s lib! I don’t hold with all that stuff.” She is the wife of a retired army officer, and a veteran of political campaigns. Meanwhile, the Republican incumbent for her Assembly district is being challenged by a feminist woman Democrat, and in Southern California the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party is seeking to abolish itself, on the grounds that a separate women’s organization is sexist in conception.

These are the extremes in the spectrum of views on women’s place in the world that the political party workers of Santa Clara County, CA reflect in their organization, their activities, and their attitudes.

Organization at the state level is set for both parties by the state code. Each legislator or party candidate has up to five nominees to the State Central Committee of his party, of whom at least two must be women. From this 1,000-strong body, a man and a woman for each Congressional District are chosen to form the decision-making executive committee.

“The women have a great deal of influence,” says Loretta Riddle, field representative and campaign coordinator for State Senator A. Alquist, who has served on the executive committee for ten years. “It has been a very fair thing. If you have the ability, and work hard, you can make your voice heard.”

The presence of a few women is customary, though not mandatory, on the elected County Central Committees. But at this level the loose structure imposed by the state gives way to local idiosyncrasies. The Democratic Party, though overwhelmingly the majority part of the county, admits to being fragmented and disorganized. The Republicans, on the other hand, pride themselves on their efficiently centralized hierarchy. Robert Walker, executive director of the Republican county headquarters, has the county committee divided into specialized sub-committees, and keeps close liaison with his party’s many volunteer clubs.

In contrast to the 600 members that the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party can muster, the thirteen chapters of Republican Women’s Club in the county have a total of 3,000 members. Ten of the clubs run their own local campaign headquarters, registering voters and handing out literature for all the Republican candidates. They are also the labor force of the campaign. “Those women are fantastic,” says Mr. Walker. “I can send them a 30,000-piece mailing and get it back the next day all ready to go.”

The Democratic women have a project too: they run the county headquarters for the party. Madge Overhouse, its director, feels that she has a strong voice in the running of the party organization. “But it is simply by going ahead and doing something like this. Within the Democratic Party you can come up with an idea and follow it through.”

“Individual effort” is an idea often expressed by Democratic women; “femininity” comes more often to the lips of Republicans. The northern chapter of the Democratic Women’s Division, though less militantly feminist than its counterpart in Southern California, puts most of its fund-raising effort into the campaigns of women candidates. Ladies’ club activities like luncheons or fashion shows, favorites of the Republican women, are not popular with Democrats. “We are more issue-oriented,” says Madge Overhouse.

The advantage of clubs, thinks Robert Walker, is that they attract people who would not ordinarily be involved with the party. He described the Republican Party as “the party of the middle class. They tend to be socially oriented, and this carries over to their approach to doing political work. They want to gain some prestige out of it.”

Joan Menagh was a founder of the Republican Women’s Club in her neighborhood. While enjoying the social aspects, she stresses that education is its primary purpose. “Volunteerism” has been a popular topic for speakers. Traditional social values prevail. Though she has worked up to a seat on the County Central Committee, and a full-time job in the office of U.S. Congressman Ch. Gubser, Mrs Menagh claims to have no political ambitions. “In my life my husband and family come before any of my other activities.”

Democrat Madge Overhouse is also critical of the more militant factions of her party. “We have to recognize that there are a good many women who are perfectly happy to be wives and mothers. The militants are cutting these women off, and I think it’s too bad.”

Nor for that matter will Loretta Riddle run for office, partly because she wants to stay close to her two teenagers, but mainly because her personality is satisfied with the considerable power she already wields behind the scenes. She does however admire women who have aspirations to high office, and is longing to see a woman in the California Senate. “I don’t think men realize how much they need women in politics. Women have a certain sensitivity and perspective that men do not.”

Both Republicans and Democrats see a trend toward more women in public office. “I think it goes back to this whole women’s lib thing,” says Republican Joan Menagh. “Women for many years didn’t feel that running for public office was a particularly feminine thing to do, and voters in the past didn’t feel that a woman could hold her own within the political arena as a candidate. Both ideas are passing.”

Democrat Loretta Riddle agrees. “People have not yet learned to accept women who are forceful. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t go ahead, because then we may go along and start learning little by little.”

The way is open for a woman to rise as high in politics as her ability, tenacity and sheer personal drive will allow. It is a difficult path though, and few are willing to take it. The vast majority of women in political campaigns will no doubt continue to stuff envelopes, sit at voter registration booths, check precinct lists, and make tea for the parched throats of campaign speakers.

Education for perspective transformation

I’ve rummaged through my old black filing cabinet to no avail; I can’t find the draft of my early 1970s interview with Georgia Meredith, director of the re-entry program for women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, CA. I liked Georgia, a warm, caring person who made every woman she met feel welcome in her college program.

Jack Mezirow with his wife Edee, whose return to college in middle age helped spark his theory of transformative learning.

I scoured the Internet, and found one reference to her, in the acknowledgments for a 1978 academic paper on the phenomenon of mid-life women returning to school. The author is Jack Mezirow, who was a professor of adult education and director, Center for Adult Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. Georgia Meredith’s Foothill College program was part of his nation-wide study of re-entry programs for women in community colleges.

Older women on college campuses were a new phenomenon in the early 1970s. Mezirow’s data show that the number of women aged 25–34 attending college rose more than 100 percent from 1970 to 1975. According to his obituary (he died in 2014) Mezirow’s interest was party inspired by watching his wife return to graduate school in middle age.

His research project’s primary thrust was “to identify factors that characteristically impede or facilitate the progress of these re-entry programs.” His findings led to the theory of perspective transformation, which Mezirow describes as “a critical dimension of learning in adulthood that enables us to recognize and reassess the structure of assumptions and expectations which frame our thinking, feeling and acting.” He writes:

“For a perspective transformation to occur, a painful reappraisal of our current perspective must be thrust upon us. Among the re-entry women whom we interviewed, the disturbing event was often external in origin —the death of a husband, a divorce, the loss of a job, a change of city of residence, retirement, an empty nest, a remarriage, the near fatal accident of an only child, or jealousy of a friend who had launched a new career successfully. These disorienting dilemmas of adulthood can dissociate one from long-established modes of living and bring into sharp focus questions of identity, of the meaning and direction of one’s life.”

He lays out ten steps in the transformation cycle:

- A disorienting dilemma;

- Self-examination with feelings of guilt or shame;

- A critical assessment of sex-role assumptions and a sense of alienation from taken-for-granted social roles and expectations;

- Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change;

- Exploring options for new ways of living;

- Building competence and self-confidence in new roles;

- Planning a course of action and acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans;

- Provisional efforts to try new roles;

- Building of competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships; and

- A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by the new perspective.

Mezirow notes that the scope of re-entry programs expanded as the need to focus on self-exploration, career development and personal growth grew increasingly apparent. Some community colleges needed to make changes in entrance requirements. In many classes, writing based on personal experience was accepted in lieu of academic knowledge of a subject. Cohorts of adult students were kept together to encourage mutual support and encouragement. Classes were often scheduled into blocks of time that fitted with children’s school time. Colleges set up child care facilities, drop-in women’s centers, resource referrals.

“All of the programs,” says Mezirow, “are clearly aware that they exist to provide specialized support for women who are effecting a transition in their lives. Since the women are at different phases in this transitional process, their needs vary. … The central goal …is perspective transformation —helping women to see themselves and their relationships in new ways, which require taking responsibility for their lives, examining their options, and formulating new life plans. It is a unique mission in higher education.”

A Language to Hear Myself

I started writing poetry in the fall of 1968. I know the date because that was the year my elder son started kindergarten and his two-year-old brother still took afternoon naps, so I had one hour to myself for the first time in five years. I chose poetry partly because it was a short form. An hour would be time, I figured, to write a line or two, or polish an image.

To write well, one needs also to read. I looked around for models. Educated in New Zealand, I had little acquaintance with American poets, and even less with work by women. (The table of contents for my college English I poetry anthology, The English Parnassus (Dixon and Grierson: Oxford 1909), contains no female names.) However, by 1968 I was already becoming acquainted with feminist ideas and literature, such as Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Over the next few years, I sought out female poets.

Anne Sexton’s work immediately caught my attention. Never before had I read poems so uninhibited in their exploration of female sexuality, mental illness, and the constraints of a conventional domestic life. I was particularly excited by Transformations, Sexton’s retelling of well-known tales by the brothers Grimm. Here’s the last stanza of “Cinderella:”

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

Sexton’s retellings bring out the essential unfairness of the old stories’ patriarchal viewpoint. Remember “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” in which an old soldier, having found out the secret of the princesses’ worn dancing shoes, gets to marry his choice of the young women? Here’s Sexton’s wedding scene:

…the princesses averted their eyes

and sagged like old sweatshirts.

Now the runaways would run no more and never

again would their hair be tangled into diamonds,

never again their shoes worn down to a laugh …

Another poet whose books are well represented on my shelves is Denise Levertov. As well as being a beautiful nature poet, she was a passionate protester of the Viet Nam war. This from “The Distance:”

While we are carried to the bus and off to jail to be ‘processed,’

over there the torn-off legs and arms of the living

hang in burnt trees and on broken walls

She also wrote of domestic tasks, such as in this opening stanza of a poem about a visit to her aging mother:

Milk to be boiled

egg to be poached

pot to be scoured.

Many other books by women poets of that era still grace my shelves: Audre Lorde, Sylvia Plath, Marge Piercy, Adrienne Rich, Diane Wakoski, to name a few. A recent exhibition of early feminist poets in the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library collection takes its title from a stanza of the poem “Tear Gas” (1969) by Rich:

I need a language to hear myself with

to see myself in

a language like pigment released on the board

blood-black, sexual green, reds

veined with contradictions

The exhibition’s introductory text by Audre Lorde sums up how I felt as I discovered the feminist poets of the 1960s and ‘70s:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is the vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we give name to the nameless so it can be thought.

Liberation by Strobe Light

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

At the opening forum, my friend Judi and I recognize a few women we know. There is a feeling of bonhomie among the attendees, I have written in my notes. After the introduction we are shown a women’s lib segment from the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family”. Women roar with approval at Gloria’s feminist attitudes, chatter noisily during commercials.

The surroundings for my first breakout session are inauspicious. Out of the rain and into a Foothill College classroom plod two dozen women like myself, suburban housewives, thirtyish to middle-aged, dripping umbrellas. The desks have been pushed back against the cream-colored walls, and the chalkboards are still scribbled with students’ assignments. Self-consciously we obey the call to take off our shoes and sit on the floor. The instructor, in powder blue leotards, is already making pumping movements with her arms.

In formal dancing, she explains, the woman is led by her male partner. But today’s kids dance apart, doing their own thing. We are going to pretend like we are kids. We heave up our sagging muscles. The lights go out. The music comes on, a strong rock beat. A strobe light flickers. I have never seen a strobe before. I am fascinated by the jumping shadows. Impossible to see any other person clearly. The classroom is disappearing, and we are no-place. Though we are crowded together, we are each alone, in our own darkness. At first we copy the movements of the instructor, but imperceptibly private fantasy takes over.

From my mother I learned to fear my sexuality. Now I am doing a sexy dance, gyrating my body in a collage of distant memories. I see again the smoky crush of teenage bodies glimpsed through a basement doorway at a country club near Syracuse, NY. It was 1962; the Twist was just coming in. Terrifying, beautiful, and my fear was mixed with envy of these kids little younger than myself, who could accept their bodies’ needs and express them freely.

My fingers flicker in the strobe light, twenty fingers instead of ten, flying over the keyboard of an imaginary concert grand. I am strong. I am ambitious. I am free. The beat of the music rises to a climax. My body is soaring to a rhythm of its own. I have flown back fourteen years, back to Syracuse, NY, back to the doorway of the smoky basement. I enter the door and mingle with the grease and sweat of the dancers. I am no longer afraid. The tape ends, the lights come on, and we flop exhausted onto the schoolroom floor.

My next workshop is titled “Changing Images.” A large wood-floored room in a gymnasium complex, walled with mirrors at both ends. Again we take our shoes off, and lie on the floor to do a relaxation exercise. “Breathe … out. Now let’s see what happens when we loosen our clothes. Those of us that have belts on, let’s undo them. Let’s unbutton our slacks. There now, isn’t that more comfortable?” We are given a little pep talk on the influence of other people on our fashion choices, then break up into small groups to discuss how we feel about our clothes. I tell about my conservative wool suit, and how mod and worldly and competent I felt when I dressed it up with cream opaque pantyhose and body-shirt to go out and do an interview. A striking single girl confesses that she usually winds up wearing a sexy dress to go to a party where there may be new men. A matron in trim blue slacks and floral shirt tells how she automatically thought of wearing a knit suit to this workshop, until she read in the paper the invitation to wear “comfortable” clothes. She wishes she could find her own style – everything she buys turns out to be too conservative for what she thinks may be the real her, yet very suitable for her role as wife and mother, church-goer, active member of the PTA at her kids’ school. We try on a few wigs and clothes. It’s fun, but inconclusive – there are not enough things to do much with.

I meet Judi at the cafeteria for lunch, and we trade notes. At her clothing workshop, the first of her day, two women had stood conspicuously at the side, refusing to soil their clothes by lying on the floor. Everyone now is very chummy. The cafeteria is crowded. I hadn’t realized there were so many women here. The luncheon speaker gives a brief potted history of the women’s movement. Her voice is rather flat, and I have read it all before anyway. I look at the mural from the morning’s painting session. It is very militant. I look for the positive, affirmative images. Not many. In a flash I know what I want to paint.

My last workshop of the long, full day is a painting session. In theory, we are to paint our reaction to the clip we were shown of the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family,” in which Archie’s wife Gloria expresses feminist attitudes and Archie berates her. But that was early this morning, at the introductory forum. A lot has happened since then.

Most women paint their reactions to the day. One painting is of a huge orange cloud, turbulent, stormy, but beautiful, and raining golden rain onto a green hillside. This was how she saw what was happening today, says the painter. The stirring of new ideas was exciting, but also scary, and in the long run it would benefit humankind.

Many women paint themselves. “This is me when I can’t cope,” writes a mother from a wealthy suburb, whose dark green and black picture shows a figure in bed under the covers, surrounded by black smoke and scary faces. Another draws a bright fire arched over by a brown form. “The brown shape is her man,” says the painter. He is both protecting her from the outside world, and smothering her fire so it can’t get out.

My image comes out fast, so fast I keep running out of paint on my brush. I draw the arms first, in dark, strong red, reaching up, hands wide open. A smiling face, a body, a quick angle of a dress to show that she is female. “Reach out!” I shout in red paint underneath. Then quickly back to the table to find some yellow paint. Bright yellow light scribbles itself behind the figure. She looks too sketchy. Pour the yellow paint into a remnant of blue to give her a green dress. Green hair? Why not? “This is where I am at,” I tell my fellow painters. “I have broken out of my chains.”

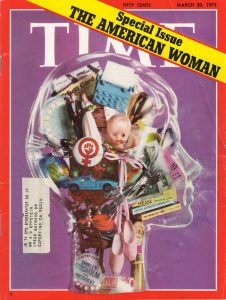

Time Magazine on women, 1972

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

The issue starts, as usual, with letters to the editor. These are from female readers responding to the magazine’s invitation to “write to us about their experiences and attitudes as women, and to tell us how their views on this subject have changed in recent years.” I tabulate the responses. Twenty enthusiastic about the new feminism, three ambivalent, and six tending negative, arguing that, since very few higher level jobs are available to women, by going out to work they “trade the drudgery of housewifery for the drudgery of an office job.” Or, as another writer put it: “Rush out each day to that exhilarating, high-paid position; rush home to that hot-cooked supper (cooked by whom?); relax in that nice clean living room (cleaned by whom?). Most likely, dearie, you’ll hold down two jobs—‘cause when you get home from that executive job in the sky, there ain’t gonna be no unliberated woman left (and certainly no man) to do your grub work.” Sidebars titled “Situation Report” in the various sections of the issue reflect these caveats: prejudice is rampant against allowing women into higher paid or managerial professions.

Time’s editorial attempts to define “the New Feminism” as “… a state of mind that has raised serious questions about the way people live—about their families, homes, child rearing, jobs, governments and the nature of the sexes themselves. Or so it seems now. Some of those who have weathered the torrential fads of the last decade wonder if the New Woman’s movement may not be merely another sociological entertainment that will subside presently.”

Subsequent pages offer a history of the currents of social change that “have converged the make the New Feminism an idea whose time has come.” There are portraits of a range of American women, a piece on “the organizations, aims, difficulties and range of opinions that help make up Women’s Liberation in all its diverse forms,” a one-page snapshot of attitudes in Red Oak, a small Iowa town. Here’s a quote: “Many Red Oak women agree with Doctor’s Wife Jane Smith: ‘A woman’s place is in the home taking care of her children. If a woman gets bored with the housework, there are plenty of organizations she can join.’” A photograph shows Mrs. Smith entertaining friends at bridge. I have a flash of memory: one of my sisters saying the same words to me.

The “Politics” section of the magazine showcases some familiar names: Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, Martha Mitchell, and describes the bipartisan effort of the National Women’s Political Caucus to get more women elected, or selected, as delegates to the Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

The “Science” section describes the difficulties a woman astronomer faced. As a woman Margaret Burbidge, who helped develop a new explanation of how elements are formed in the stars, “found that she could get precious observing time at Mount Wilson Observatory only if her husband [a physicist] applied for it and she pretended to act as his assistant.” The Burbidges also ran into nepotism rules at the University of Chicago. “’The irony of such rules,’ says Mrs. Burbidge, who had to settled for an unsalaried appointment while her husband was named a fully paid associate professor, ‘is that they are always used against the wife.’” I think of women scientists I have known who suffered the same exclusion, such as Beatrice Tinsley, a British-born New Zealand astronomer and cosmologist whose research made fundamental contributions to the astronomical understanding of how galaxies evolve, grow and die. Beatrice had to divorce her husband, a Texas University professor, and move to Yale to gain the position she needed to do her work.

In many science fields, recognition for outstanding women is still abysmally low. I think of efforts by my son David, a mathematician, to redress the paucity of profiles of eminent women mathematicians in Wikipedia.

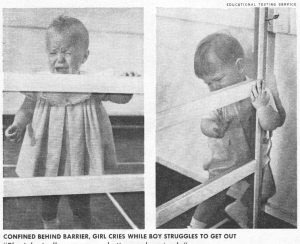

Section after section, the stories continue. “The Press” section is subtitled “Fight from Fluff,” how women’s pages are shifting to more general interest features. ”Modern Living” talks about efforts to find new pronouns, the opening of day care centers, and changes in marriage dynamics. The Situation Report for the “Law” section puts the number of women lawyers in the U.S. at 9000, 2.8% of the total number of lawyers. Of this small number, “less than 12% of them were making more than $20,000, as compared to 50% of the men.” Similarly depressing are statistics for recognition of women in the arts, in business, and in medicine. The “Behavior” section, which looks at research into sex-related differences in early childhood, seems to reinforce stereotypes: “Many researchers have found greater dependence and docility in very young girls, greater autonomy and activity in boys.” The accompanying pictures show two babies behind a barrier set up to separate them from their mothers. The little girl cries helplessly; the boy struggles to get out.

A keynote essay by Sue Kaufman, author of the novel Diary of a Mad Housewife, attempts to capture the feelings of a composite American woman, interested in the new ideas, admiring of feminist leaders, but cautious about jumping on the bandwagon. Kaufman describes an imagined scene: an admired leader is coming to town to speak. The woman arranges for a babysitter. “She will go, usually with friends. They will arrive … take their seats—and slowly it will begin to happen … she begins to feel the flickers and currents of a mass communion, a rising sense of excitement that she imagines parallels what one feels at a revival meeting … this powerful thing happening, this sweeping, surging, gathering-up-momentum feeling of intense camaraderie, solidarity movement.” After the meeting is over, Kaufman describes the woman driving home, paying the sitter, returning to the children and the kitchen “to take up the reins of her existence. Only—something is wrong. She is overwhelmed by a terrible sense of wrongness, of jarring inconsistency. There was that surging, powerful feeling in the hall, and now, stranded on the linoleum under the battery of fluorescent kitchen lights, there is this terrible sense of isolation, of walls closing in, of being trapped. …but she doesn’t burst into tears. …In spite of the desolation she feels, she knows that she is not alone…there is enormous comfort in knowing that. And knowing that is one of the big changes in her life.”

Recycling centers: the old days

Rummaging through my old black filing cabinet, I came across an article I wrote in 1972 about recycling centers that was published in my Christchurch, New Zealand paper. These days, when everything recyclable gets dumped into the Blue Bin and carted away, I though it might be fun to read about the beginnings of the movement.

Rummaging through my old black filing cabinet, I came across an article I wrote in 1972 about recycling centers that was published in my Christchurch, New Zealand paper. These days, when everything recyclable gets dumped into the Blue Bin and carted away, I though it might be fun to read about the beginnings of the movement.

COME ON DOWN TO THE RECYCLING CENTER

Cupertino, CA

Spurred on by their ecology-minded kids, Californian families these days are loading up the station wagon at weekends with squashed cans, bottles, aluminum foil, and old newspapers, and heading for the local recycling depot.

The movement started a few years ago, when beer manufacturers discovered that they could earn bonus points in public relations by buying back and recycling the aluminum beer cans that had become an inevitable part of the landscape of the nation’s beaches and parks. As concern for the environment became a national obsession, clean-up campaigns became a fashionable, and profitable, project for youth groups.

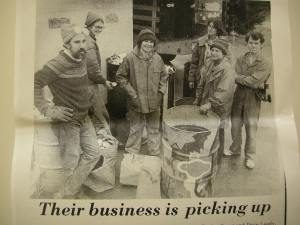

A 1970s recycling center. Image from Bainbridge Island, WA Community Cafe

Then the kids started taking over the collection depots. Each summer, high school social studies departments set up their own recycling centers. Sometimes the logistics of getting students organized can be overwhelming. One summer the boxes and bottles piled up embarrassingly high in the parking lot of a local supermarket before the kids from the high school across the road got themselves coordinated. And last year student apathy on the prestigious Stanford University campus allowed the recyclable trash to spread like a slum over the elegant grounds.

But a well-run recycling center can be a pleasure to visit. A Los Altos youth group set up shop in the grounds of an abandoned school. Every weekend enthusiastic volunteers were there, sorting, packing, stacking. Cheerful hand-lettered signs directed customers to the right cardboard carton for each item, and warned about the broken glass on the ground. One member invented an ingenious wooden lever for pressing the cans as flat as can be, and this is always in use, though most families now bring the stuff in already sorted and squashed. “Doing your bit for ecology’ has become an acceptable chore for children, and there is a therapeutic value in bashing cans nearly comparable to chopping firewood, back in the good old days before central heating and all-electric kitchens.

Some local government projects have fared less well. Neighboring Sunnyvale’s municipal recycling center is a lonely outpost in the corner of the city dump, way down in the swamp beyond the aerospace plants and the defense installations. Not surprisingly, the center made a loss last year.

Cupertino has tried to get the best of both worlds. The local chapter of Jaycees, supported by the city, the college administration, and the students’ Ecology Corps, has set up a recycling depot in a corner of the beautiful, and central, De Anza College grounds. It is less chaotic than the Los Altos center: a neat redwood fence surrounds the area, and the materials are contained in big steel skips. But there is still the sense of community involvement, the cheerful bustle on a Saturday morning, the satisfying clunk of bottles smashing into the skips. First quarter earnings showed a modest profit. The glass and aluminum are bought back by their respective manufacturers, and the tin and bi-metal go to a local producer of nursery pots.

Some recycling centers take newspaper, which is now reused for a variety of items, from dinner napkins to stationery. But the youth club paper drive, long a part of American life, takes care of most of this, and the big brown newspaper skip on the local school grounds is a familiar part of the landscape.

What about the future? Development suggestions have included a return to the regular garbage collection, with automatic sorters at the dumps to pick up reusable materials. The idea sounds more efficient, more appropriate to industrial America. But somehow it doesn’t quite fit the new environmental consciousness, with its emphasis on individual effort. And it won’t be nearly so much fun.

A discovery in the sky

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken

—John Keats

A letter to my parents:

31 March 1970

…This morning we had another memorable experience: Tony got us up at 4:30 am to see Bennett’s comet, which is visible in the east at this time. This is believed to be a new comet, and is an extraordinarily beautiful sight, with its huge tail trailing. Can you see it from New Zealand?

The Southern Cross and its Pointers. Image from Te Ara–Encyclyopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz

Since I was a child, learning from my father how to find due south from the Southern Cross and its Pointers, I have been fascinated by the night sky. In my homeland of New Zealand I could point out some of the interesting phenomena: the Coalsack nebula, the Magellanic Clouds. An immigrant to the Northern Hemisphere I was still learning the northern sky.

In 1970 I was too busy with children and their needs to study more about the new comet. I’ve now learned that it is considered one of the greatest comets of the past century. It was discovered on Dec 28 ,1969 by an amateur astronomer, Jack Bennett, in Pretoria, South Africa. It seems we have a southern constellation in common. From his obituary I learned that Bennett, who died in 1990, “became interested in Astronomy when as a teenager, his mother used to point out to him the Southern Cross and the brightest stars and planets, in the evenings after church service, on their way back home.”

Daniel Verschatse took this 1970 photograph of Comet Bennett near the town of Waasmunster in Flanders (Belgium).

The astrophotographer Daniel Verschatse notes on his website:

“For two decades, starting in the late 1960’s, the southern sky was patrolled by a dedicated South African comet-hunter named Jack Bennett. Using a 5-inch low-power refractor from his backyard he discovered two comets. Jack also picked up a 9th magnitude supernova in NGC 5236 (M83), becoming the first person ever to visually discover a supernova since the invention of the telescope.”

I also learned that Comet Bennett is estimated to have a period of 1700 years. So if it previously appeared in Earth’s sky, it would have been in the third century, about the time that the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great was a baby. Britain was still under Roman rule. In my ancestral Ireland, Cormac mac Airt reigned as High King from his seat at Tara.

The Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny) atop the Hill of Tara, County Meath, where the High Kings of Ireland were traditionally installed.

Comet Bennett’s next perihelion, or point at which it is closest to our sun, is predicted to be the year 3600. Might it still exist by then, and might there be humans left to see it? Who knows?

The nesting instinct

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

Feb. 2, 1970

… I cleaned the apartment, then of course rushed back here to try to get a bit more cleaning up and unpacking done. The previous owner was a pretty sloppy housekeeper – still, I guess everyone complains about the other woman’s methods. Anyway, most of the house is now more or less presentable …

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Or, as webmd.com puts it: “Just as birds are hardwired to build nests for protecting their young, we humans are primed to create a safe environment for our new offspring.”

I wasn’t pregnant in 1970, so I looked up sites with information on spring cleaning. I found checklists, some tentative discussion of the custom’s origin in ancient traditions and religious practices, as well as practical reasons for the task, especially in places of cold winters and times of sooty wood- and coal-burning heating facilities. And on sites about moving into a house, there were checklist after checklist, all of them assuming that the previous owner/tenant is by definition a germ-carrying slob, and that the new occupant is motivated to clean every inch of the place. A few examples:

From Angie’s List:

- “Previous residents surely cleaned the bathroom, but there is no harm in scrubbing away your own way as this room can be one of the more germ-filled places in the house.”

- “The insides of all cabinets and drawers were most likely ignored by the previous tenants or homeowners.”

- “Dust the top of the doors and disinfect all doorknobs.”

From Bed Bath & Beyond:

- “Your dream home sure looked spotless during the open house. But gird yourself: No matter how clean the place seemed, it’s likely there are some dirty surprises in store for move-in day.”

[This site pays particular attention to chandelier light fixtures, crown moldings, ceiling fans, doors & knobs, refrigerator vent, dishwasher, furnace, ductwork, washer & dryer]

From The Spruce:

- “You should always do a thorough clean before your stuff arrives.”

- “The kitchen is probably the first place to start. Not only because it tends to be where icky sticky things collect, but also because you’ll want to get rid of the former tenant’s cooking smells.”

[Detailed instructions for fridge, stove, cabinets, counters, sink, walls, floors]

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

In celebration of friendship

Browsing through letters from my early years in California, I am struck by how often new names crop up: work colleagues of Tony’s who invited us to their homes, families we met at a playground or children’s event, neighbors. I realize now that my parents often had no idea who I was talking about. It didn’t matter. Having no family nearby, our new friends loomed large in our lives. We did our best to reciprocate, but it never felt like enough. Here are some examples from early 1970, when we were moving from the apartment complex into our new house:

Browsing through letters from my early years in California, I am struck by how often new names crop up: work colleagues of Tony’s who invited us to their homes, families we met at a playground or children’s event, neighbors. I realize now that my parents often had no idea who I was talking about. It didn’t matter. Having no family nearby, our new friends loomed large in our lives. We did our best to reciprocate, but it never felt like enough. Here are some examples from early 1970, when we were moving from the apartment complex into our new house:

Feb. 2, 1970

The chaos is gradually dying down here. We moved in a week ago on Sunday, but don’t think we could have done it without our incredibly good friends. Al & Jim provided manpower & car to help with the furniture, while Judi & Margie not only took care of the kids, but provided meals for everybody all day. And this with Judi pregnant and nauseous, & David running a temp. of 103°. … I have not been too well this week either… Again, Margie came to the rescue, & had David & Simon over there while I cleaned the apartment …

I am having Margie’s kids tomorrow while she takes visiting family to Monterey for the day…

Feb. 15, 1970

Several of my new neighbours gave a coffee morning for me on Friday – very pleasant, though naturally a little stiff & formal – but it is nice to be formally introduced to people. Then this afternoon the husband of one of the women I met came over & made himself known to Tony, which was rather nice. And of course, my old friends from the apartments have been dropping in.

Feb. 28, 1970

Between downpours I have been digging a hole to plant a young live oak that the Gaubatz’s have given us – some bird or squirrel planted it in their yard, but now it has to go to make way for an extension to their house. It is a lovely specimen, so I hope it survives the move. We were up there last weekend also, & Don G. showered us with all sorts of bits for the garden – calendula seedlings, shasta daisies, calla lilies, violets, artichokes, and thornless blackberry. In return we are giving them a pair of podocarpus trees that look very stiff by our front door, and a half-starved rhododendron that someone planted too close to its fellows.

Practically all the people we met in Silicon Valley were immigrants, either from other countries or other states of the US, all of us heady with the intellectual ferment of the new technologies, all of us just another foreigner among the many. What mattered was that we took care of each other, respected our differences, and learned from each other. Some of these friendships have lasted for decades, even through moves to other towns and changes in life situations.

In these troubled times, it feels important to celebrate the values of friendship and caring. Thank you, all my dear friends.

The appeal of the picturesque

I’ve been wondering: what is it about an old house or barn that appeals so much that we describe the scene as “picturesque.” The question came up as I reread a January 1970 letter to my parents describing the purchase of a house in Cupertino, CA. Our new home was a typical early 1960s tract house with scalloped trim and prominent garage. The place was certainly not picturesque, but it was within our price range. I wrote:

It’s a very nice little house – 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, big sitting room with dining area at one end, small family room opening to a neat little kitchen, 2-car garage with laundry facilities in it. Very attractive inside, though not very prepossessing from the outside. However, this is just a matter of landscaping – other houses in the street are just lovely, but the garden of this one is just bare grass.

Looking back on that time, what comes most vividly to mind is another house I saw while house-hunting, a charming old farmhouse dating from the time when the Santa Clara Valley was so full of orchards it was called “The Valley of Heart’s Delight.” As I walked through with the realtor, I paused in what must have been a utility porch and mud room. The unfinished walls of the room were black with mold. The realtor shrugged when I pointed it out. The price was right, but I chose not to make an offer.

There’s a significant difference, of course, between the picturesque, which has been defined as that kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture and a habitable structure for humans. But what is it in the human psyche that is drawn to the antique? Rummaging around on the web, I found quotes such as:

(esp. of a place) attractive in appearance, especially in an old-fashioned way

A picturesque place is attractive and interesting, and has no ugly modern buildings.

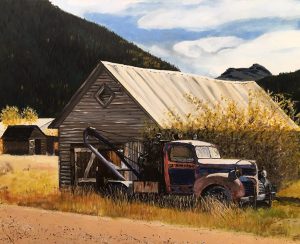

My friend Sandy Peters says it well. Commenting on a Portola Art Gallery exhibition of her husband Jerry Peters’ paintings of old battered trucks in rural settings, she wrote: They demonstrate how the beauty of nature blends seamlessly with the wisdom of age.

However, with age comes death. When we first moved to Mendocino seventeen years ago, a cabin stood among the trees along Highway 128, not far north of Yorkville. Its bare board were gray with age, the sway-backed roof shingles covered with moss. Over the years, the roof has slowly caved in, until now the cabin is a jumbled pile of boards. At first it was picturesque. Now when I drive by, I am sad.