Archive for the ‘family’ Category

Sitting down with lions

In many cultures, humans see themselves as siblings to other living beings. In Aotearoa New Zealand, where I grew up, the Māori people recognize landforms such as mountains and rivers as their relatives. Even in Western Judeo-Christian societies, where humans are believed to have been make in God’s likeness and to have dominion over all creatures (Genesis 1:26), people with beloved domestic pets may discover that their relationship is closer to that of peers than of master and subject.

My own views, which come closer to those of scientific pantheism, had a formative moment one summer day in the early 1970s, when my friend Judi and I took our children to the Oakland Zoo. I tell about it in a letter to my parents:

A lion cub recently born at the Denver Zoo. Image from the Denver Post.

The biggest thrill of the day, I got to cuddle a lion cub. Little 7 week-old roly-polies, they had been separated from their mother – I gather the father was threatening to harm them in the cramped quarters of the adult lions. We happened to be there at bottle time, and the keepers brought them out to a low platform in the children’s zoo. They obviously need lots of affection. I was sitting on the platform, and one of them just crawled into my lap, like a kitten or a puppy.

I will remember always the roughness of the cub’s fur under my hand, the warmth of his tiny body, the loudness of his purr, the overwhelming sense of awe that this wild creature trusted me. Here’s a poem about the incident:

The Lion Cub

In the dusty heat of the zoo

a lion roars.

I conjure a dream of Africa

an endless veldt

an alien majesty

concealed in yellow grass.

At the petting zoo

three lion cubs

explore a patch of dirt.

I sit.

One crawls into my lap

nuzzles my hand.

Under thick baby fur

muscles ripple, relax

curl up for a nap.

Wide-eyed, the children watch

and touch.

Distance evaporates.

We are earth family

connected deep in time

in mother love.

How we came to live in Mendocino

We’d never been camping before as a family when, in the summer of 1971, Tony and I decided to take our children, then eight and five, on a short trip to explore some of the northern part of California. On our return, I wrote an ecstatic letter to my parents:

The beach at Russian Gulch State Park, looking under the bridge to the sea. Image by David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons.

25 August 1971

I guess I haven’t told you about our camping trip. We had a marvellous time, and are really sold on camping. We hired a 9×9 tent, and bought a pup tent for the boys, a propane stove and lantern, and a very nice ice box, so we were pretty well set up, and the state park campgrounds are really very civilised, with your own picnic table and food cupboard, and running water, bathrooms and showers not too far way. We spent five nights at Russian Gulch, which is on the Mendocino coast, about 200 miles north of here. This really is a delightful spot. The sea coast here is very rugged, with steep cliffs and caves and tumbled rocks, and grassy meadows on the headlands, with pine and redwood forests behind. The gulch is made by a lush little creek that flows into a tiny cove, making a perfect beach for the children, and the campsites are straggled along the edge of the creek, sheltered from the sea wind, and with a view of redwoods high above you. The weather was beautiful – only a trace of fog a few mornings, and it can be thick all the time. The children got very used to going for long walks, and we also spent a lot of time just sitting and unwinding and watching the wildlife – lots of jays, rabbits, chipmunks and garter snakes. The anchovies were running in the cove, so thick they were being hauled in by waders with nets, and of course they attracted the bigger fish. We were sitting on the beach one afternoon when a group of scuba divers came along with a huge catch, and offered us some, so we had fresh cod for supper.

After describing our impressions of Mendocino village – “splendid weather-beaten old buildings, many of them fine examples of carpenter Gothic, very similar to New Zealand colonial period architecture” – the letter continues:

From Russian Gulch we went on up the coast highway then inland to the Humboldt Redwoods. These are very lovely and impressive, but I think our hearts were still at Russian Gulch.

Here’s where the story takes a mythic turn. Here’s how I tell it now:

Once upon a summer afternoon a man and a woman sat on a beach. As the couple sat and gazed, a young man emerged from the sea. He was beautiful, with golden hair that hung to his shoulders and a body that had known good exercise. From each of his hands hung a fish, whose scales shone wet and silvery.

The woman called out, “Nice catch!” to the fisherman as he passed.

He paused. “Would you like one?”

The woman’s fingers flew to her blushing face. “Oh no, no, I didn’t mean …”

The fisherman lingered. “Please. I have more than I need.” He held out one of the fish.

The man sitting with the woman rose slowly to his feet. The fisherman placed the fish in his out-stretched hands. The man bowed his head and murmured his thanks. That evening, the man and the woman cooked the fish over their campfire and ate its sweet flesh.

After the man and woman returned to the city, every now and then they would feel a tug, as if they were being played on an invisible line. They would say to each other, “We need to go back to that place.” So they would rent a house on the coast for a week or two. The sea sang to them, and each evening a golden light would seep like an enchantment across the drowsy headlands. When their time was up, they would return sadly to the city.

In this way thirty years passed. Each year the tugs grew stronger, the city more and more unbearable. At last they could resist no longer. They left the city. In a house close to where they had eaten the fish, where the scent of the sea came to them, they quietly lived out their days.

A legacy of crocheted lace

A comment in an old letter to my mother catches my eye:

March 1, 1971

I can’t remember anything about that bit of crochet, Mum, but I guess it probably is mine. Now it will sit in my workbox for years!

Do I still have it? I open the Cadbury’s Chocolate box that holds my collection of crochet hooks and sundry balls of crochet thread. On top sits a small piece of lace, obviously the beginnings of an ambitious project. Was it the piece that cluttered Mum’s workbox? Probably.

The art of crochet was honored in my mother’s family, passed on, like all domestic arts, from generation to generation. The most noted expert was my great-grandmother, Sarah Jane Caundle, whom I met a few times when I was a child. She was born in 1864 to Irish immigrants on a New Zealand goldfield. In a reminiscence my mother wrote:

Outside the back door [of Grandma’s house] in the sun was a stool to sit on. Across the yard in a shed that housed the wash house with its copper and wooden tubs with the toilet next to it. Grandma washed the clothes in the old way with a well-stoked fire under the copper to boil the sheets, etc. The tubs for the rinsing and blueing with a hand-turned wringer between them. While visiting as a small girl I was being taught how to crochet. Trying to make my doll a pink woolen petticoat like the ones Grandma made for us. Something would not go right so I called for assistance. There was Grandma coming across the yard at her usual jog-trot wiping the soapsuds off her arms on her apron (Must always wear an apron) to sort out my muddle. The picture is still so clear in my mind.

… As we grew older we were given doilies and crochet-edged linen for our “box.” At each 21st birthday each granddaughter was presented with an afternoon tea cloth with a wide edge of crochet lace.

Before she died in 1951, Great-Grandma Caundle had started making doilies for her great-granddaughters. I missed out, but inherited a piece of her work from my mother. Fascinated by Mum’s stories about her grandmother’s life, I put together a poem:

Great-Grandma’s Doily

Early afternoon, when chores were done,

Great-Grandma put her feet up on the kitchen couch

and gave herself an hour with crochet hook and thread

to figure out the sequence from a photograph—

chain and double loop and treble—

the mathematical progression of the rounds

revealing patterns satisfying in their laciness.

She learned the art at her mother’s knee

in the dirt-floored hut at the Puriri claim.

Her mother learned it from her Mam

back in Ireland before famine memories

and rumors of gold in the far-off colonies

took Bernie Donnelly and his new young wife

adventuring across the world.

There was a dame school at the diggings.

Great-Grandma might have gone some days

but not enough for fluency in letters.

She had sisters and brothers to mind,

manuka-twig brooms to fashion for the floor,

clay to fetch for the hearth’s weekly whitewash of mud.

She entered service as a housemaid at eleven.

Later came marriage and children of her own,

nine of them, then grandchildren to care for.

All this time persisting in her art,

gifting to daughters and grand-daughters

lacy linens for their marriage chests.

I have one doily, handed down, an oval of white linen

edged with a crocheted frill of tulips in a row,

each stitch pulled neat and tight, a testament

to discipline and practice, and the will

to make time for her art.

A spat in slow motion

A spat between parent and adult child is different when conducted on flimsy blue international air letter forms. For one thing, it happens in slow motion: weeks pass between riposte and retort. For another, it’s solitary: neither side can see the angry tears of the other. And it’s documented; that is, if letters are kept. My mother kept all mine, and gave the bundle back to me. I constantly regret that I didn’t keep hers, so have to guess at the comment to which a letter of hers or mine would have responded.

A typical example happened in late 1971. Decades later, as I read through my old words, I recognize patterns of individuation familiar to every psychoanalyst.

It started with a postscript to a birthday thank-you note my six-year-old son had written on Nov. 13, 1971.

At the bottom of the page I’d scrawled:

Do I assume that you have given up writing to me?

Mum’s response, as I remember it, was to the effect that if she wrote to one member of my family, it was to be assumed that she was thinking of us all. Here’s my response:

Nov. 23, 1971

I’m sorry that you got so uptight about my comment, Mum. However, I think we should clear up some basic misunderstandings about the children. I am delighted that you have written to them, and they are too. They think it is pretty special when an adult relative takes an interest in them. But it is very important to me that the kids be seen as individual people, with interests and responsibilities of their own, and this includes developing communications with other adults outside the immediate family. This, I think, is a reaction to my own childhood, when you tended to take over any attempts we made to establish relationships with other people. Now don’t get upset – I’m just trying to show you how I see myself, and how I see my kids. If you only have time to write to the kids, that’s O.K. I’ll encourage them to answer your letters, but there may be some long gaps. They are not big enough yet to handle a regular correspondence. But I have no intention of taking over the responsibility for them, nor of regarding your letters to them as some sort of gimmick substitute. I am an individual person too, and I haven’t had a letter from you since August.

We made up our differences in the next round of letters. In response to her plaint about the difficulty of being a parent, I wrote:

Dec. 14, 1971

I know what you mean, Mum, about bringing up kids. I sometimes wonder what these two will hold against me when they grow up, and it’s sure to be something I’ve never thought of.

Rumblings in the socialist paradise

I sold this early 1970s article about feminism in New Zealand to a US magazine. Unfortunately, the journal folded just after I’d received the galley proofs. Disappointing, but hey, these things happen. Reading the galleys again, I recognize many of my own frustrations, and understand a little better why I had to leave. I realize, of course, that New Zealand society today is very different from what it was then.

Letter From New Zealand

In New Zealand we say it is the land that shapes the people.

The land is lovely, but aloof; it has not welcomed intruders. For a few square miles the forest and scrub have given way, but the houses sit impermanent as boxes on the clearings, and in the towns the raw suburbs perch in self-conscious rows.

Europeans have been here for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain they brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. Together these two strands wove a welfare state that, in providing an economic floor beneath which no family can fall, has codified the disparities between the sexes, and underlined the definition of woman as housewife.

In the 1930s and ‘40s the pattern of social experiment these pioneers began reached its flowering in a social security system that offered a minimum wage, compulsory arbitration of wage disputes, pensions for invalids and deserted wives, family allowances that can be capitalized into housing down payments, low interest housing loans, low rent state houses, and a national health service that provides free medicines and medical treatment. A school dental service provides free dental care for all children. Most recently, in April 1974, an accident compensation scheme went into effect that covers everyone on New Zealand soil, whether earning money or not.

It is a complacently comfortable floor. But at its foundation is the assumption that the only proper place for a woman is in the home taking care of the children.

The welfare of the child is the prevailing argument. Says Norman King, New Zealand Minister of Social Welfare: “The majority feel that a close relationship with its own mother is the birthright of the New Zealand child. We do not want to encourage the adoption of a lifestyle in New Zealand where it becomes normal for the care of very young children to be a specialist task carried out by trained staff in group situations away from the family.”

New Zealand women achieved the right to vote in 1893, second only to Wyoming. Otago University in N.Z. admitted women to degree courses in 1871, the first in the British Empire. There are today very few women Members of Parliament, and no women at all in the administrative levels of higher education. Those who have reached positions of authority in any field are regarded as exceptions to the norm. And in a country as small as New Zealand, to be different is to be disapproved. A friend who returned home after ten years in London says: “Everything in New Zealand presses on me to settle down, to conform, to live safely, not to take risks.” My elder sister, Evelyn Stokes, has a doctorate in geography from an American university. Hostile vibrations still echo in our family over her decision to place her two children in a day care nursery so she could continue her university teaching.

Official thinking assumes that a mother who goes out to work does so either from economic necessity or from disproportionate greed. The idea that women might have talents other than domestic comes hard to New Zealanders. It is certainly not fostered by our education system, which from the start locks children into rigid sex role definitions.

From six-year-old Donald, Evelyn Stokes’s son, comes a crumpled school paper.

Check what toys girls like, he is instructed.

Big and little dolls? Yes, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A train? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A football? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

At the high school level the curriculum encourages vocational discrimination by sex: academic girls are steered towards the arts rather than the sciences, and average girls towards secretarial or home-craft courses.

But the winds of rebellion, fanned by global news services and travelers’ tales, are stirring the curtains at the kitchen windows. Women are staying at school longer and leaving with higher educational qualifications than ten years ago. The percentages of women and of married women in the work force are still lower than most western countries. But their numbers are increasing steadily, despite recent changes in the family benefit structure aimed at dissuading mothers from going out to work. Equal pay recently became law, and will be at least nominally applicable to all areas of the workforce by 1978.

Social custom compounds the problems of those married women who do go out to work.

Pat Brown has her own advertising agency. She told me that a company party with her husband, chief chemist at a freezing works, she attempted to discuss with his colleagues the implications of advertising and the sale of meat. Her husband’s boss took her firmly by the hand and led her to the far side of the room, where the other wives were discussing babies and knitting patterns. “This is your place,” he said.

Domestic duties are another stumbling block. Marriage counselor Marianne Thorpe says: “The difficulty is that women feel that they are responsible for the care of the home and children (and they get almost no help in this task), and this makes working outside the home a complicated business.” Evelyn Stokes and her husband Brian, head of math at a teachers’ college, share responsibility for housework and child care. It is an unusual set-up for a New Zealand family. More typical is Ray Lealand, now retired after a double career of clerical work and home-making, who says: “The most difficult problem I faced whilst working was non-cooperation from my husband.”

Role demarcation in some families is incredibly rigid. One friend recalls the raised eyebrows in her family when as a young bride she took on the vegetable garden. “That’s the husband’s job,” she was told. “The wife does the flowers.”

Since most women expect to stay home once they have a child, the idea of maternity leave is not widely accepted. When Evelyn Stokes applied for leave for the birth of her second child, the committee set up to look into the matter came back with a regulation that a mother who applies for maternity leave “is required to satisfy the university that her additional family duties are compatible with the continuation of her employment.”

Child care facilities for working mothers are inadequate, and though support for day care centers was a major plank in the ruling Labour Party’s 1972 election platform, its implementation has been whittled down to a subsidy to needy children in existing voluntary centers. Part-time employment coinciding with school hours is widely accepted, but employers will take on mothers of preschoolers only as a last resort, and use the argument of family responsibilities to pin women to the lower scale, “temporary” job classifications.

Sex role definitions still apply in employment. Six occupation groups employ 65% of New Zealand’s working women: clerical, sales, clothing manufacture, teaching, nursing, and domestic service. But there has been some movement into the traditionally male areas of drafting, electronics, and electrical work, and into the newer technological jobs like computer programming or systems analysis, where sex-exclusive traditions have not yet calcified. With a shortage of male labor in many fields, a few pioneers are braving the public ridicule and breaking down job opportunity barriers. One such incident, in 1972, even rated media coverage. Two girls applied for jobs in an Auckland factory as aluminum glaziers, only to be told this was not a woman’s job. When they asked “Why not?’ no answer could be found, and they were taken on.

This thread of social change is closely woven with another that is a constant in New Zealand life. Few in numbers, and isolated by thousands of miles from the sources of our culture, we have been almost pathologically dependent on the word from the outside world. I remember my first beat as a cub reporter; I scurried round the tourist hotels of Christchurch, winkling out startled visitors and begging them to express an opinion. Any opinion. Still the pattern continues. Articulate voices from abroad, no matter what their status, receive far more attention than local expects on the same subject.

The feminist movement is a case in point. Local groups springing up in the past few years have found a climate of hostility and ridicule. The ideas of American feminists, distorted by distance and by different cultural norms, have seemed to many to be irrelevant to the New Zealand experience. Then early in 1973 two visitors coincided: Evelyn Reed, an American Marxist feminist who advocated abortion law reform and improved child care facilities, and Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist know for his work on the deleterious effects of maternal deprivation on a child’s mental health. Both, basking in the aura of the magic words “from overseas,” were taken seriously by the local press. Margot Roth, editor of the Journal of the N.Z. Society for Research on Women, comments that the resulting controversy opened up a much wider range than usual of questions concerning women, and helped lay the foundation for the success of a United Women’s Convention held September 1973 in Auckland to mark the 80th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

The purpose of the convention, according to the organizers, was to correct the distorted view New Zealand women had of modern feminism, to raise the status and self-confidence of women, and to increase the numbers of women willing to work on behalf of women’s issues.

Statistics indicate that the fifteen hundred women who attended, while better educated and more likely to be employed than the average, nevertheless made up a remarkably accurate cross-section of New Zealand society. The issues discussed were those that concern women everywhere: job opportunities, control of their bodies, marriage and child care, sex stereotyping.

Press reportage of the Convention again sought to trivialize and ridicule. Afternoon TV revealed to local mums some of the hogwash poured down the verbal ducts at the United Women’s Convention, reported one city daily.

However, rage over press flippancy reinforced a feeling of unity at the conference, and the consensus of those who attended is that, for the first time, women from the whole range of backgrounds and interests in New Zealand life experienced a feeling of sisterhood.

The floodgates are open. Women with common interests are pooling resources. The prestigious National Council of Women, umbrella for all women’s organizations in New Zealand, and for long a stronghold of the traditional view, is now espousing the cause of equality and encouraging its affiliated groups to contribute.

It is hard to say what the future will hold. Though New Zealanders travel the world as casually as migrating godwits, jet planes cannot eliminate the sense of lonely isolation that makes us belittle our homegrown prophets. The land still broods, raw, stubborn, and the people it has bred still revere the sheep shearer above the artist. On embroidered tablecloths, housewives still set teas of cream cakes and scones, and rows of preserves still gleam on pantry shelves.

But the women of New Zealand have a stubborn streak too. Diffident, shy, self-conscious in proclaiming the ideas that come from an almost alien American culture, we are nevertheless gathering strength. The spirit that made New Zealand one of the most comfortable societies in the world may yet take a mattock to the scrublands of tradition, and graze the new fields of equality.

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

Night train in winter

New Zealand’s Volcanic Plateau in daytime. Image from https://www.flyingandtravel.com/skiing-north-island-whakapapa-ruapehu/

An image haunts my mind like an old song in a minor key. From a train window late at night, a desert plateau spreads into the distance. In the foreground, scattered clumps of tussock, stiff with frost, emerge from a dusting of snow. On the horizon, three volcanic cones gleam white against the blackness. The scene is both bleak and beautiful. Tranquil even. A calmness fills me as I remember.

The year was 1968, the place the center of North Island, New Zealand, somewhere north of Ohakune on the Main Trunk Line. I was traveling by train, alone, to a funeral.

It had been a tense few months since my husband and I, with two young children, had decided to make the trip back to New Zealand, our home country, to visit our families. First there was boundary-setting to do with my mother on how much relation-visiting I would allow her to inflict on my shy infants. A few weeks prior to our departure date the children developed chickenpox, one after the other, pushing our schedule further into New Zealand’s winter and upending an itinerary that carefully divided our limited time between my husband’s family and mine. On arrival, I discovered my mother had sabotaged this division by taking a motel room in my mother-in-law’s town. Each day she ensconced herself in mother-in-law’s tiny living-room, dragging my embarrassed father and school-age sister with her. Other sisters later told me they’d remonstrated with her, but she’d insisted she had a right to see her long-gone daughter as soon as I arrived. My mother-in-law was gracious, but I was furious on her behalf.

Then fate intervened. On a night of heavy rain, my maternal grandmother’s husband stepped from between parked cars into the path of an oncoming truck. I did not know my step-grandfather, since he and grandma married about the time I left for college. But grandma had been an important part of my childhood, and she loved this man, so it mattered that I go to the funeral. Leaving the children with their father and his mother, I set out on the overnight journey. First a railcar from New Plymouth, on the west coast, which connected at Marton with the Night Limited express that ran each night between Auckland and Wellington.

I knew this train, having ridden it back and forth many times when I was in college. There was comfort in the familiar sway and smell of the overheated, stuffy carriage, the faded red plush covering high-backed seats, the clackety-clack of the wheels. There was peace too. For the first time since the children were born I was alone, with no responsibilities.

Beyond the desert and mountain vista on the Volcanic Plateau, the chuff and grind of the diesel engine became more labored as the narrow-gauge track rose into a more broken landscape, with forest a dark overhang outside the window. Then Taumarunui Station at 2:00 am, the refreshment stop, where bleary passengers streamed into the tea-room for meat pies or slabs of yellow pound cake and milky tea in thick white china cups. Sometime around dawn, a stop at Te Kuiti where relatives met me for the two-hour drive to Tauranga, where the funeral was to be held. Calmed by the journey, I willingly renewed acquaintance with uncles and cousins and aunts I’d argued with my mother about seeing.

Looking back, I understand what that spare, snow-covered landscape was telling me: that the land is vastly more important than human quarrels, that I needed to let go of my day-to-day tensions and anxieties and become merged with the wholeness of the earth.

The best laid schemes

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley

–Robert Burns

I’ll never forget how furious my mother was with me that day. I was about seven years old, and spending the day at my grandparents’ house while Mum ran last-minute errands. The next morning my parents, sisters and I were to leave on a camping trip, the first real vacation my family had ever had; Dad was an auto mechanic, and summer was his busiest time, with all the beach-goers flocking into our seaside town and needing help with their vehicles.

That afternoon I started to feel poorly. Grandma felt my forehead and promptly tucked me into bed. By the time Mum bustled in to pick me up the cause of my misery was obvious: my body covered with the red blisters of chickenpox.

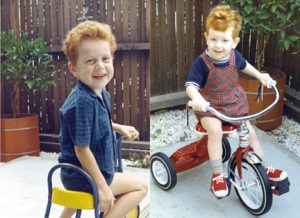

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

11 May 1968

I did write to you earlier in the week, but it was obsolete before it was even posted, so I tore it up instead. Isn’t this business just typical of kids? Anyway, here is the present state of play: we have bookings … [revised details]… But this flight depends on Simon [our two-year-old] coming out in spots this weekend, or Tuesday at the latest. The chances are higher that we shall postpone again until the following week …

Here is my calculation of the odds: Incubation period 11-21 days. Say David came out in spots on the 11th day, and Simon, from the same contact, on the 21st day (i.e., next Friday) he has two weeks to have it over with.

Say Simon missed David’s contact, and gets it from David, he can come out in spots on the 11th, 12th, or 13th day, and has 11 days, or a reasonable chance, to be free of scabs. (The airline will take him if a doctor will certify that he is not contagious.)

Say Simon decides not to get it at all, he will have passed the 21st day by two days.

The only problem will be if he gets it from David after the 13th day. The 14th day is borderline; after that we would have to cancel. We are in a bit of a quandary as to what to do then … Meanwhile we are all twiddling our thumbs, and willing Simon to produce ‘chickenpops’, as he calls them. It seems such an awful thing to do to such an innocent little poppet, but so far he has remained obstinately clear-skinned and perky…

The ironic thing is that we had a mumps crisis last week. One of the children’s closest friends came down with mumps about two weeks ago. We flapped around for a while, seriously considered gamma globulin, in spite of the cost (about $60 just for shots for myself and the children). We had braced ourselves to go through with it, when at the last minute the doctor just couldn’t get hold of any, so decided to try a new mumps vaccine instead. This is a lifelong immunity, but doesn’t take full effect for a month. By this time, he hoped that the vaccine would have built up enough antibodies to resist the disease. So far it is working. It is quite interesting being guinea-pigs, and considerably less expensive, at only $5 each. So instead we get the chickenpox!

…I have just come in from a walk – after four days in the house with kids, I needed it, but have come back feeling more depressed than ever about the whole business.

Monday – Have postponed until 31 May…

20 May 1968

Believe it or not, Simon actually produced some ‘chickenpops’ today, so we have started believing again that we are really coming. … I’m still not really convinced that we will arrive, but as we are going in this Wednesday to pick up the tickets, I had better stir myself out of this legarthy.

The irony of this story is that when we finally arrived at Nandi, Fiji on our way to New Zealand, the immigration officer noticed that David’s smallpox vaccination was outdated. (You needed this at that time to get into New Zealand). In our panic over chickenpox, we has totally spaced on this detail. Fortunately the officer was kind “Just get it done as soon as you get there,” he said as he stamped our papers.

Uncles & cousins & aunts, oh my!

Recently, while reading Michael Krasny’s new book, Let There Be Laughter, I came across the Yiddish word naches, which Krasny defines as “the joy and pride a parent derives from a child’s accomplishments.” High on a mother’s list of accomplishments for her daughter would be the production of beautiful grandchildren. It was an ‘Aha!’ moment. I’d been re-reading some of my 1967-68 letters to parents (my mother saved them all and gave them back to me) and thinking about the strained mother/daughter relationship the letters revealed.

The occasion was our first visit back to New Zealand. It had been seven years since we left our birth country, and twelve years since I had spent more than a week or two with my parents. In the meantime I had earned an advanced degree, begun a career as a writer, married, moved to England, had a couple of children, moved to California. I had kept in touch faithfully through fortnightly letters but had had none of that face-to-face interaction that helps define a relationship.

I was wildly excited about the trip:

18 Sept. 1967

I have a bit of news that I have been saving up, partly because I still scarcely believe it myself – we are hoping to come for a visit to NZ about the middle of next year, probably in May. It will only be for a month – you get a cheaper excursion rate for 28 days – but hope that will be long enough to see everybody again, & for the children to sort out who all the vague names of grandmas, uncles, etc. are – David [our 4-year-old] has them hopelessly confused at the moment.

1 Oct. 1967

[On news that sisters & cousins were having babies] It will be fun to meet all these new members of the family – they certainly seem to be mounting up.

31 Oct. 1967

[re Christmas presents] Like you, finance is a bit low this year – as you can imagine, we are needing to save very hard for this trip.

My next letter has a firmer tone. With the help of a marriage & family therapist friend (thank you, Linda G.), I’ve been researching the psychology of mother/daughter relationships and discovered the Jungian concept of individuation, the process of becoming aware of oneself as a being separate from one’s parents. I also learned that tensions are normal in the parent and adult child relationship during this process of separating and setting boundaries.

17 Nov. 1967

I gather that preparations are already being made for our homecoming in May. I hope you realise that our time is going to be extremely limited. We hope to divide most of it between you & [my husband’s mother], but also must go to Christchurch for a few days, and also have friends around the country that we hope to visit. So you would do well to reckon on about a week (don’t forget flying time is included in the 28 days). This week will have to include relations too. The plan for an open day or weekend sounds a good one. I had better make it plain from the start that, apart from our immediate brothers & sisters, and possibly grandparents if they are too infirm to travel, we are not going to do any relation-visiting. For one thing, it wouldn’t be fair to the kids, dragging them round from one set of strange faces to another. If you are going to get to know them at all, which from our point of view is the purpose of the visit, we will need a quiet domestic atmosphere with as few strange faces as possible. It took David four months to adjust to living in this country. Also, two days of being an exhibition piece is about as much as T. or I could stand – we are pretty unsociable types!

Here’s where the Yiddish concept of naches comes in. Looking back, I realize now that it mattered deeply to my mother to be able to show us off. She had never seen our children, her first grandchildren, other than in photographs, and she had idealized them. But as a young mother, I was having none of it:

5 Dec. 1967

Glad you see my point about visiting relations, though reading your letter again I have a suspicion that you intend to have them turning up all the time anyway. If this is so, please think again. I know, Mum, you love to have your family about you, and find it hard to understand my attitude. But to me my family is my husband and children, and next, my parents and brothers and sisters. Now I shall be delighted to meet all my uncles and my cousins and my aunts, but since practically all of them are almost total strangers, it would be much easier on us to restrict their visits to a definite two days, and leave us free for the rest of the time to do what we came for, which is to visit you.

In my psychology reading I came across another concept, filial maturity, explained as:

1) By early adulthood, particularly in the 30s, taking on the responsibilities and status of an adult (employment, parenthood, involvement in the community), the child begins to identify with the parent.

2) Eventually, the parent and child relate to each other more like equals.

When I wrote these letters about our forthcoming trip to New Zealand I was 29. After fifty years of being a mother and a grandmother, I now understand why my mother and I were at odds. I’m sorry she had to deal with such a difficult and demanding daughter. I also know this was the way it had to be.

The shapes of family

I still remember the tongue-lashing my teenage cousin and I received when we defended our widowed grandmother’s decision to file for divorce from her second husband. If the two of them couldn’t get along, we saw no reason why they should have to stay together. Mothers and aunts rounded on us. We didn’t know what we were talking about, they scolded. Grandma was a disgrace to the family. The Mother’s Union of our Anglican Church was going to throw her out, and her daughters were ashamed to show their faces in town.

Tauranga, New Zealand, was a tightly traditional little town in the 1940s and 50s, when I was growing up. Fathers worked, mothers stayed home with children. I didn’t know any single parent families. If there were divorcees, they were invisible. So were lesbians and gays.

My social environment in England was almost as sheltered. My friends were other young marrieds with small children. Our close of new row houses was filled with intact families like ours.

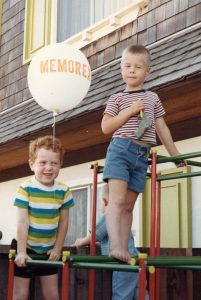

When we moved to Cupertino, CA in 1967, we lived in a complex of townhouse apartments. Each apartment had a 20 ft. by 10 ft. fenced yard. Our yard was filled with a climbing tower, a sand box, sundry tricycles, pushcarts, and other paraphernalia to keep our two small boys entertained. The neighbors helped open my eyes to other family structures: single parents, grandparents raising kids, abusive relationships.

The memory of my grandmother’s divorce comes back to me as I read a letter to my parents. After thanking them for our two-year-old’s birthday gift, I wrote:

17 Nov. 1967

Simon had a lovely little birthday party – a lunch for three little friends – after school the apartment is invaded with older kids, which would have caused problems. We seem to run a regular play centre here, what with the climbing tower and sandbox, and the new easel, with apparently unlimited supply of crayons & paper. However, the opportunities for recreation are so limited in these apartments, and so many of these kids from broken or otherwise mixed-up homes, that I guess its our contribution to the community.

There’s a self-righteousness tone to this comment, an indication of my awakening to the variety of household shapes in this new environment. A hint of defiance too. I wonder, was I getting back at my mother and aunts for their dismissal of my grandmother’s decision so many years ago?