Archive for the ‘family’ Category

In Praise of Parks

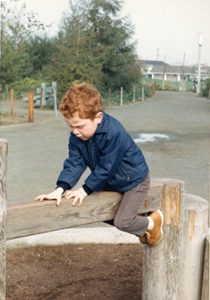

Having spent all their little lives in a place where parks had prim Keep Off The Grass signs and irate men in bowler hats with sticks enforced The Rules, my children were enchanted to discover the parks and playgrounds of their new home.

In the 1967, when we arrived in California from England, California State Parks was going through a huge expansion. Appropriations from the General Fund and a 1964 recreation bond provided well over a hundred million dollars for land acquisition and development. The government budget analysis for 1967 comments:

In the immediate future, the most pressing need of the state park system will be to provide funds for access and minimum development to enable the public to use lands now owned or currently being acquired. The existing state park system has a potential for development of about four times that of existing facilities.

With an expanding population, local governments in the Santa Clara Valley were also opening new parks and playgrounds as rapidly as they could. It was a fine time to be kids. They had their choice of playgrounds within easy driving distance: the one with the great swings, or the one with the good bars to climb on?

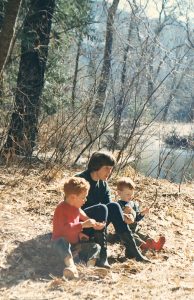

Cooking out at a forest park was one of our favorite activities. We bought a cheap little hibachi, loaded up a picnic and were off to explore.

At weekends, if the weather was hot in the valley, we might go over the Santa Cruz Mountains to the beach, remembering to take warm jackets since the fog was likely to roll in. Again choices, choices: Pescadero State Beach, or San Gregorio, or Half Moon Bay, Natural Bridges, Seacliff, Manresa…? Well before the California Coastal Act of 1976 declared that the permanent protection of the state’s natural and scenic resources is a paramount concern to present and future residents of the state and nation and that it is necessary to protect the ecological balance of the coastal zone and prevent its deterioration and destruction, the beach parks in our part of the state were already a beloved treasure.

Looking back, I recognize how innocent we were about land use politics, environmental pollution issues, climate change. Now more than ever, those parks and beaches, and the creatures living in them, need our support.

A sisterhood of neighbors

Would she be able to watch my toddler for an afternoon while I went to a doctor’s appointment, I asked Margaret, my next-door neighbor in the block of new row houses we’d both recently moved into in 1965. An odd look came over her face, and a blush reddened her cheeks. A pause. “Actually, I have a doctor’s appointment that afternoon too.” Another pause. I don’t remember which of us said it first: “I think I’m pregnant again.”

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

Not having family in England to call on for help, I am forever grateful to this sisterhood of neighbors. Most of the women in our little close of twenty houses were stay-at-home mums with small children. We drank coffee together in the mornings and shared how our brains were turning to mush. Our children ran in and out of each other’s houses. We took care of each other.

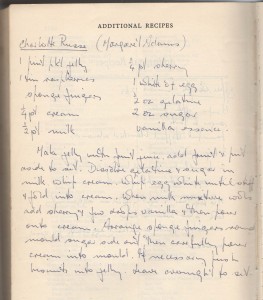

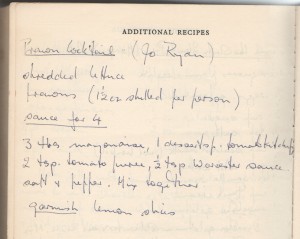

On the back pages of my English cookbook are two recipes, one for a Charlotte Russe from Margaret and a prawn cocktail from Jo, both classic 1960s recipes. I remember the occasion vividly. My husband Tony had accepted a position in California. We were waiting for our US green cards to come through –a nerve-wracking saga that I’ll write about sometime. Meanwhile, his prospective new boss was passing through on his way home to Denmark for Easter, and wanted to meet Tony. A dinner invitation was obviously required. But what to serve? In a panic, I turned to my sister-neighbors. They held my hand and helped me through planning a menu. Prawn cocktail to start, and Charlotte Russe for dessert. For the main course I probably served roast lamb, a traditional New Zealand staple.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

Oh, to be shoe-less in the summer sun

My sister Alison’s family, gathered in New Zealand for Christmas. It’s summer there, that time of year. Note the absence of shoes.

My old black filing cabinet has yielded a treasure: the carbon copy of a 1960s letter to a newspaper editor. Reading it again, I’m struck by how much it reveals about my homesickness for the more casual lifestyle of New Zealand and my resentment of the strictures of English custom. I was reminded of these differences when my sister Alison, who lives on a beach north of Auckland, posted on Facebook a photo of her gathered family, and American friends of the family joked about the lack of shoes. Here’s the 1964 letter:

The Women’s Editor

The Guardian

Manchester

Dear Madam,

As a fellow colonial I share [Guardian feature writer] Geoffrey Moorhouse’s feelings about English clothing habits. The conformity begins at an early age. This summer my one-year-old toddler and I have been subjected to cold stares and even sarcastic comments from total strangers. The cause is his shoe-less feet. I am obviously considered a poor mother, for not providing leather for his feet, and looking round, I noticed that even during the hottest days, while my infant sat comfortable in only napkin and sunhat, most of his contemporaries were firmly laced into heavy shoes, and many were even inflicted with neatly buttoned shirt and tie.

I am not against shoes on principle. Now that the weather is turning cold, my son wears shoes and socks with his long trousers. But I do object to this pressure to dress young children according to society’s idea of respectability, disregarding the dictates of the weather.

I don’t go barefoot in Mendocino. It’s cold here, and there’s burr clover and native blackberry underfoot. But sometimes I miss those carefree New Zealand summers of my youth.

The red stain of near disaster

Whenever I see old blackberry canes, dark red as the stain of their summer juice, I remember blackberrying in England when my son was small, and a dark red guilt sweeps over me. I described our expedition in a letter to parents:

8 Oct 1965

We went blackberrying on St. Ann’s Hill, not far from here. Got a lovely lot—have been busy making jelly, pies, etc. David had a wonderful time—it was so sweet to see the solemn single-mindedness with which he set about collecting his berries—and he didn’t eat a single one until Tony offered him a handful—to comfort him when he tumbled down a slope into a patch of brambles.

Modern American parents would probably be horrified at how lackadaisical we young mothers in England were about supervising our children’s play. Once the daddies were gone to work, our little close of twenty-eight row houses was almost completely free of traffic. The kids, twenty of them under school age, ran in and out of each others’ houses and romped together across the grassy front yards.

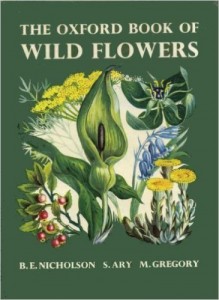

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

While Tony, who had come home from work for lunch, went to tell the mother of the other child what had happened, I tried everything I knew of to make our baby throw up. Nothing worked. We called an ambulance. Since I was within a week or two of giving birth to our second child, a neighbor, seeing the ambulance, came over to wish us well. I am still grateful that when she learned the story, she called the police, and still guilty it hadn’t occurred to me that other children might be involved. Some days later I wrote to parents:

Watercolor illustration by Barbara Nicholson in The Oxford Book of Wildflowers, Oxford University Press, 1960. Shown are: Comfrey, Common Mallow, Musk Mallow, Deadly Nightshade, Duke Of Argyll’s Tea Plant, and Woody Nightshade.

13 Oct. 1965

The police organised all the rest of the kids in the close whose parents couldn’t prove they were somewhere else that morning into another convoy of ambulances for a mass stomach pumping session. About a dozen altogether involved, of which four (including David) were confirmed cases, though they decided to keep the whole lot overnight for observation, just in case.

Meanwhile the newspapers had got hold of the story. We refused to see them at the hospital, but when we got home about 7:00—completely exhausted, & having had nothing to eat since breakfast—we were invaded by a posse of reporters. A highly garbled & exaggerated account appeared the next day. I suppose it’s not every day one makes the front page of the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, & the BBC News, but I shouldn’t care for the honour to happen again.

Anyway, the story ended well—all the kids were discharged the next morning, with none but the hospital staff any the worse for wear—in fact the sister-in-charge of the children’s ward where the confirmed cases were confessed that she hadn’t known that four such tiny boys could get so involved in riots and punch-ups all up and down the ward, and they were very pleased to see the back of them.

Fingernails on glass

The visiting baby, almost two years old, sat alone and silent by the ribbed glass door of our row house in Egham, on the outskirts of London. He paid no attention to our chatty, energetic infant of the same age, nor even to his parents. Instead, he ran his tiny fingers obsessively over the ribs of the glass. Watching him as I fixed tea for our guests, I was uneasy.

A letter to my parents dated 20 April 1965 says nothing of this unease. Instead:

We had visitors on Sunday – Steve & Derek Shirley & their little Giles, who is the same age as David. We hadn’t seen them for quite a while, & had a very pleasant day.

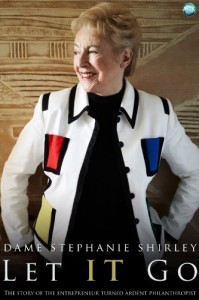

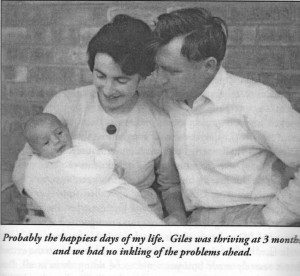

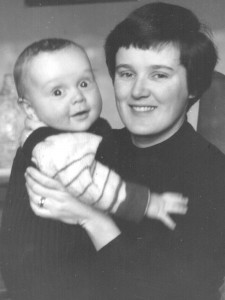

That was the last time we saw the Shirleys. Recently I have been reading Dame Stephanie (Steve) Shirley’s memoir Let IT Go, to try to understand what happened to our year-long friendship. The answer is devastating.

In early 1964 I had interviewed Steve by phone for an article that ran in the Guardian about women programmers and her new business Freelance Programmers. A few months later I gushed to parents:

30 April 1964

A couple of weeks ago we went to visit a very pleasant couple – the woman I interviewed (over the telephone) for my article on computer programmers. She has a baby the same age as David, and also works at home making up programmes – that is, the detailed instructions to be fed into a computer to do a required job. Anyway, we liked each other very much even over the phone, and she invited us to a meal to meet properly. They have a marvellous little stone cottage up in the Chilterns, right out in the country, with apple trees and daffodils, low oak beams, a huge log fire, and a grand piano squeezed into the front parlour. It sounds like a setting from a romantic novel, and that was the feeling even when we were there, that everything matched so well that it couldn’t be quite real. And a remarkable affinity too, between us as people. A bond to start with of course — it was the interest of her story that got me a place in the Guardian, and she credits me with the terrific boost to her business – she now has 20 other home-bound women working for her, and is forming herself into a limited company, and with giving her the confidence to get started. Then Derek is also a physicist [like Tony], reserved, very musical, and Steve and I found that our feelings and ideas agreed on all sorts of points.

At that time Giles and our David were eleven months old. Steve writes in her memoir:

The catastrophe had crept up on us. It must have been in early 1964—when he was about eight months old—that we first began to worry, on and off, that perhaps Giles was a bit slow in his development: not physically, but in his behaviour. He was slow to crawl, slow to walk, slow to talk; he seemed almost reluctant to engage with the world around him. These concerns took time to crystallise—as such concerns generally do—and the first time I went to a doctor about them I couldn’t even admit to myself what was worrying me. …

My letters for the rest of 1964 are full of references to our new friends: visits back and forth, parties, conversations. In June I wrote: We liked them even more, if possible … isn’t it strange how people sometimes just click.

Meanwhile, Steve writes:

By the end of that year, however, there was no avoiding the observation that Giles was losing skills he had already learnt. … [He] had never become chatty. And now he fell silent. …

Months of desperate anxiety followed, in which there seemed to be little that we could do except fret. …

My lovely placid baby became a wild and unmanageable toddler who screamed all the time and appeared not to understand (or even to wish to understand) anything that was said to him…

By mid-1965 Giles had taken up weekly residence at The Park [the children’s diagnostic psychiatric hospital in Oxford] while the doctors there tried to work out what was wrong. Nothing I can write can capture the enormity of the sorrow that that short sentence now brings flooding back to me. …

Finally, in mid-1966, the specialists overseeing Giles’s case [at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children] delivered the devastating but unarguable verdict: our son was profoundly autistic, and would never be able to lead a normal life.

I understand now that our friendship with the Shirleys could not survive. Being with us would have been painful for them. There was too much unspoken, too much contrast between their child and ours. For a short time, we loved them. Even now, a sadness returns.

Postscript

Derek and Steve spent the rest of Giles’s short life seeking appropriate and supportive care for him. (He died at age 35.) Steve’s business flourished. She has poured her considerable wealth into philanthropy, primarily to support “projects with strategic impact in the field of autism spectrum disorders.”

Dame Stephanie Shirley: Let IT Go, Andrews UK Ltd., 2012

Pregnancy under a national health system

My old black filing cabinet has yielded up a statistical treasure: an article I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper about the National Health Service’s maternity benefit program in England in 1963. I was pregnant at the time, and financially stressed, so the detailed information was particularly relevant to me. I was also young and impatient with bureaucracy, hence my railing about what seemed excessive form-filling. Keep in mind that the British pound numbers need to be multiplied by 30 to get an approximate equivalent in current US dollars.

A CHILD OF THE WELFARE STATE

Having a baby in England is a (welfare) state occasion. From the moment that a pregnancy is confirmed, an expectant mother can expect to be cared for by the state in practically every detail, down to a monetary allowance for buying clothes.

The services provided are similar in many respects to those in New Zealand [which also has a national health system]. The main difference seems to lie in the number of forms requiring to be filled out for every aspect of care. When she goes to her doctor, the woman will have already filled out a form applying to be placed on the doctor’s list, and she will have received a national health card, which she presents at each visit.

It will have to be decided where the baby is to be born. Unlike New Zealand, where admission to a maternity hospital is practically automatic, most babies in Britain are born at home. Recent reports have suggested that the infant mortality rate could be greatly reduced if more babies were born in hospital, but this raises the problem of inadequate bed space. Some effort is being made by the government to increase the number of hospitals, but it is clear that for many years yet admission to a maternity unit will be restricted to those who have good medical reasons for being there. Next in order of preference are those whose homes are inadequately provided with such facilities as running water. It is usually considered advantageous to have a first baby in hospital, although this is not always possible, and space is provided where possible for mothers having their fourth or later children.

If the baby is to be born at home, ante-natal care is provided by the family doctor and the midwife who will be attending. If the mother is granted a place in a hospital, she goes to the clinic which is run by a team of doctors and nurses from the hospital. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Expert specialised attention is given at the clinics, compared with a family doctor who may, or may not, be deeply interested in obstetrics. Against this are the advantages of seeing the same person at each visit. It is quite possible to see a different doctor at each visit to a large clinic, with the resultant irritating repetition of questions. This lack of rapport, as well as the great pressure of time on the clinics, hinders many women from asking the questions that may be troubling them. The government recently released plans to set up more clinics, which may relieve the pressure a little, but it is difficult to see how much of the mass-production atmosphere can be avoided.

During her pregnancy a mother is provided with several benefits from the state. She receives free dental treatment: normally dental patients contribute the first ?1 of their dental bills, and the health service pays the rest. She receives welfare foods—a pint of milk a day at about half price during her pregnancy, and until her child is five years old. The health service’s own brand of dried milk is provided where necessary. She is also offered cheap orange juice, cod liver oil, or vitamin A and D tablets. These products are free to those who apply to the National Assistance Board claiming hardship.

The state also provides cash benefits. To allay the hardship often suffered when a married woman gives up her job to have her first baby, and to make it easier for her, in the interests of herself and her baby, to give up work in good time before the birth, the state pays her an allowance of ?3 7s 6d a week. To qualify, she must have been paying the full rate of national insurance. It should be explained that health benefits are not paid directly from taxation, as in New Zealand, but from regular weekly contributions to a national insurance scheme. It is possible for a woman, when she marries, to contribute only a nominal sum to the scheme, and to claim on her husband’s contributions for medical benefits. However, if she chooses, she can continue to pay at the single rate, and thus become eligible for these extra benefits.

All mothers, whether working or not, are given a cash grant of ?16 to help with the general expenses of having a baby. A further sum is paid if more than one child is born. In addition to this, those women who have their babies at home are given a home confinement grant of ?6 towards the extra equipment needed.

Needless to say, all these benefits depend on the filling in of forms, and presenting them at the right time. The time limit for each benefit varies, but local national insurance offices are usually helpful about coping with the confusion.

Once the baby is born, the state’s child welfare service, under the local Medical Officers of Health, takes over. This provides a service similar to New Zealand’s Plunket Society, on a nationalised level. The child welfare service is notified by the hospital or midwife of the birth, and within a few days a health visitor calls to take particulars. (Why do they always want to know the husband’s occupation?) She also gives details of the local child welfare clinic, which provides a weighing service, and advice on feeding and other problems.

Home help services are also provided, to look after children while the mother is in hospital, or to help the mother in the home.

For those who can afford to dislike the mass production methods of the national health service, there is an alternative in private treatment. Private maternity hospitals are not subsidised as they are in New Zealand, and attention by an obstetrics specialist and delivery in a private hospital would cost at least ?100 in England, and probably much more. But even with private attention, the patient is still entitled to the maternity grants and welfare foods.

Little boys in their own words

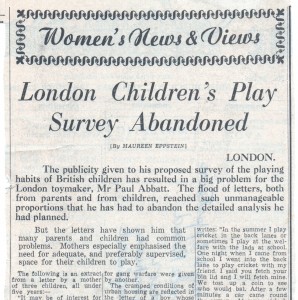

A few months after I interviewed Paul Abbatt, the London toymaker and child development theorist (see my previous blog piece, “An advocate for junk heaps”), I called to ask about his planned survey on what children actually did in their outdoor play. He sighed. The response had been so overwhelming that he’d had to abandon his plans for a detailed analysis. But he did share with me a sampling of the letters he’d received.

The follow-up story I wrote for my New Zealand paper, the Christchurch Press, was published in November 1963. It is transcribed below.

London Children’s Play Survey Abandoned

The publicity given to his proposed survey of the playing habits of British children has resulted in a big problem for the London toymaker, Mr Paul Abbatt. The flood of letters, both from parents and from children, reached such unmanageable proportions that he has had to abandon the detailed analysis he had planned.

But the letters have shown him that many parents and children had common problems. Mothers especially emphasised the need for adequate, and preferably supervised, space for their children to play.

The following is an extract from a letter by a mother of three children, all under five years:–

“It may be of interest for you to know that Crawley is a New Town—the so-called ‘Planner’s Dream.’ It is a ‘Mum’s Nightmare.’ My neighbourhood has no children’s playground, and has not had one for four years. So my children play in the road. Afternoon walks are too often an uninteresting march down roads of which the uniformity is quite paralysing.”

The mother of a boy of eight years says she could do with an attendant in the nearby park, “so that we would not be afraid to let the boy play there alone—an attendant to keep in check the bullying of older boys and help in case of accident with the swings. So, although only 100 yards away, he never goes.”

Many letters from mothers and particularly those from the children, showed children’s love for simple things, and places to make dens. A small boy of 10 gave detailed instructions on how to make a camp in a tree or cave, with the concluding remark: “Then all you need is some things to put in.” Another boy described how he and his friends caught rats on an allotment. A boy of 11 started his letter: “One Saturday when we didn’t know what to do we decided to go on a bike ride.” After several adventures they came to a secret place that one of them knew. “We went down a bank very slowly and we turned into a kind of glade. It was great. There was a stream flowing by and a smashing high tree to climb.”

Looking for the tracks of wild animals was a special memory for one boy, while the letter of another resounded with such names as Steam Engine No. 62004, Class Q.6 and Diesel Deltic, Type 5, No. D9007. Detailed rules for gang warfare were given by another.

The cramped conditions of urban housing are reflected in the letter of a boy whose favourite sport is cricket. He writes: “In summer I play cricket in the back lanes or sometimes I play at the welfare with the lads at school. One night when I came from school I went into the back lane to play cricket with my friends. I said you fetch your bin lid and I will fetch mine. We tost up a coin to see who would bat. After a few minutes a car came round the corner. At seven o’clock my mam came to the door and told me to have a bath. I went in unhappy.

“In the winter when the days are shorter and it’s dark at four o’clock I play football in the lane. Sometimes when it is raining I have a game of football in the yard. One day I kicked the ball that hard, I heard ‘smash’ one pint of milk rolling down the yard.

“Cricket is my best sport. One time my dad was having a game of cricket with me; he was in batting. I bowled, my dad hit it with such a ‘wham’ he smashed the window.”

Coldness depends on what you’re used to

A letter dated April 5, 1963 has set me to thinking about how the human body adapts to temperature differences. Tony and I, and my sister Patricia, who lived with us in Windsor, England, were luxuriating in warmer weather after the Big Freeze, the coldest winter Britain had seen for over 200 years. We’d survived ice-covered walls and windows and frozen pipes, with two paraffin (kerosene) heaters our only source of heat. (There was also a wall-mounted electric heater, but it gobbled shillings and half-crowns as if it were starving.) Then our elder sister, Evelyn, arrived from Syracuse, New York, where she had been completing her doctorate. Her letter to our parents, published in her “Letters From America 1960–1963” (University of Waikato, 2005) tells the story:

I am sitting huddled over the paraffin heater in Maureen’s living room… I am still not acclimatised. This place is so cold and I miss American central heating. Here it is cold both inside and out; there is no escape. I am wearing nearly all the clothes I possess, it seems, and I sleep under a mountain of blankets, but still it is cold. In Syracuse, though it is snowing and below zero outside, once inside we took off all our heavy coats etc. and just a cotton blouse, skirt and sandals were sufficient. I am not used to wearing all these clothes all the time, but I guess, if you live here long enough, you get used to it.

On our way to England the previous March, Tony and I visited that apartment in Syracuse where Evelyn lived with fellow students from South East Asia. Dirty snow lined the streets, the sky was gray, the apartment a stifling 80 degrees.

Evelyn left space in her letter for me to add a paragraph:

…It isn’t really as cold as Evelyn makes out, although today I must admit is rather bitter. But while the rest of us are dehydrating in the hot-house fug inside, she still complains of the cold, so I don’t know what we can do.

Pat, Tony and I would surreptitiously open doors and windows, but nothing could stay open for long. We all suffered.

A little poking around the internet informs me that getting acclimated to temperature differences typically takes about two weeks, a bit longer for adjusting to cold than to heat. This makes it hard for travelers who spend only a few days in one place. People who live in extremely hot or extremely cold climates have adapted over the eons. In arctic areas they have large, compact bodies with relatively small surface areas from which they can lose their internally produced heat. In addition, they have made technological changes such as insulated clothing and houses, and cultural adaptations such as sleeping in a huddle with their bodies next to each other. In hot parts of the world people are more likely to be tall and slender, with low body mass, and to limit their activities to cooler parts of the day.

For the past 15 years I’ve lived in Mendocino, CA, where the average temperature ranges from the mid-40s to the low 60s Farenheit, and 75°F is a hot day. The county seat, Ukiah, where we sometimes have to go for business or medical appointments, is inland, or as we say, “over the hill.” There the summer temperature average is in the mid-90s and my body tells me: Nah, that’s way too hot. How can people stand it?

Good old days at the post office

In December of 1962, before there were mail codes or mechanical sorters, I worked for a week at the post office in Windsor, England, helping with the Christmas rush. I mentioned it in letters to parents:

18 Dec. 1962

…Hope this reaches you in time for Christmas – along with the other thousands of tons of mail being posted this week. I know – I have to sort the stuff. I am spending the week working in the sorting room at the post office. Very difficult job! – turning the stamps up the right way as the letters come out of the postbags. Have to work pretty hard, but it’s rather fun – very cheerful, friendly crowd – and good money.

26 Dec. 1962

…I had a very interesting week in the Post Office. Halfway through the week I was promoted to sorting, which was a bit more fun, though harder work than facing up.

Those were the days, before email, Facebook, Twitter and other social media, when the annual holiday greeting card was how one kept in touch with extended family and friends. According to Wikipedia the custom of sending greeting cards has a long history, dating back to the ancient Chinese. The postage stamp was introduced in England in 1840. Cards started being mass produced by the 1850s. From then on, mailboxes became crammed each December with penned good wishes.

Every card and letter had to be sorted by hand. Mechanical sorting, which depended on reducing the address to a machine-readable form, came in a few years after my stint at the Windsor post office: the 5-digit ZIP code was introduced in the U.S. in 1963, and England’s alphanumeric postcode system in 1966.

Communication methods have changed, and fewer greetings now go by “snail mail.” The U.S. Postal Service reports that First-Class Single Piece Mail; that is, mail bearing postage stamps, such as bill payments, personal correspondence, cards and letters, etc., declined by 47 percent in the decade 2005–2014. But that urge to reach out to those we love during the holiday season is still with us.

A single knitting needle

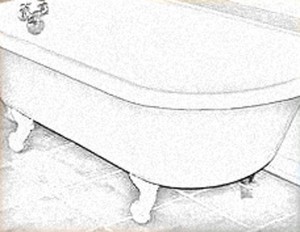

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The flat was part of a semi-detached house dating from the 1870s. The bathroom could have been original. The floor was covered in black and white checkered linoleum, worn white in front of the chipped hand basin. Above the claw-foot tub was a rusty gas-fired contraption that roared to life when you turned on the faucet. The toilet was down the hall, in a more recent addition to the building.

That knitting needle haunted me, as gradually I came to realize it was probably the instrument of an attempted abortion. I longed to know the story of the woman who had pushed it through the crack between the tub rim and the wall. Did she survive?

The conservative New Zealand society in which I grew up had such deep silences around anything to do with sexuality that I was nineteen before I even encountered the word “abortion.” It was in a letter from my mother. “Look it up,” she wrote, her stock response to any question having to do with the body. Mum’s news was that a girl I knew in high school was dead: a move to the city, an affair with a married man, a botched back street abortion, septicemia, the police phoning her parents, saying contemptuously Come and get your kid.

I too have known the desperation of an unwanted pregnancy. I went into marriage in 1960 with what today would seem unbelievable ignorance about sex. The kind ladies at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Christchurch fitted me with a diaphragm and instructed me in how to use it. But the contraceptive methods of those days had a high failure rate. Within a month of the wedding I was pregnant. My new husband was furious with me for stymying his plans to go abroad and make his name in science. I was terrified of the alien life form taking over my body. I tried to recall from novels I’d read how female characters sought to make missed periods come. Scalding hot baths—I tried that. Long, long walks—tried that too, into the seedier parts of the city. If I were to find an abortionist, it would be here. But I had no idea how to find one, and no-one to ask. Besides, I didn’t want to die, like my high school friend.

In time my resistance eased. I was, after all, a respectably married woman. I began to look forward to having a baby. My husband and I postponed the date for our departure to England, and informed the shipping company that we would be traveling with an infant. When our daughter was stillborn, I was devastated, both by the loss, and by the thought that I was being punished for not wanting her in the first place. I buried my grief and guilt deep inside and got on with my life. It took me twenty-five years before I could speak about what had happened, and finally begin to mourn.

In California in the early 1970s I made the acquaintance of a lawyer who had filed an amicus curiae brief in Roe vs. Wade. Together we celebrated that important Supreme Court decision, which affirmed a woman’s right to control her own body. Today I am dismayed that so many people seem to have forgotten, or maybe never knew, what the options were for women when abortion was illegal. The decision to end a pregnancy is never easy. But I, for one, don’t want to go back to the days of the knitting needle hidden under the bathtub.