Archive for the ‘family’ Category

Hurricane at Sea

We skirted a hurricane (known as a cyclone in the South Pacific) for the first several days after my husband Tony and I left Wellington, New Zealand, bound for New York on the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt.” For most of that time I lay on my bunk, so seasick I wished I were dead just to get the misery over with. In a letter to parents I scrawled: “Mountainous heaps of water piling up all over the place, wind changing direction all day …Steady old JVO bobbing around like a cork. Thank goodness I have got my sea legs at last – after the first few days of utter misery in a very stuffy cabin. Am still on a largely dry bread and water diet – lost a terrific lot of weight. But have been reading Women of New Zealand today and decided that my lot is not too bad after all. What those women had to put up with on their voyage out to NZ makes me feel rather ashamed of myself.”

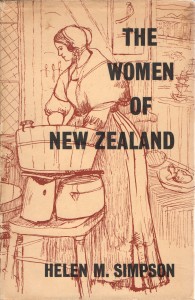

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The Ship “Kenilworth” Outward Bound for New Zealand. An illustration in Helen M. Simpson’s The Women of New Zealand, it is a reproduction of a painting by J.C. Richmond, now in the possession of the National Art Gallery, Wellington.

An early chapter describes conditions on board the emigrant ships for the four- to six-month journey from the British Isles to New Zealand. Simpson comments: “Cramped quarters ashore are difficult enough to deal with; at sea, when with every lurch of the ship ‘all things animate and inanimate’ were hurled about, children and chairs in terrifying and noisy confusion …”

Our quarters on the JVO were certainly cramped. Our lower-deck cabin had two bunks and a tiny washbasin in a space so narrow we had to take turns getting dressed. Outside in the corridor, the airless heat was rank with smells from the nearby galley. But unlike those early emigrants, we didn’t have to cook for ourselves, or bring along our own cabin furnishings.

I think of my own ancestors who braved the outward journey. A hundred years before Tony and I walked up the JVO’s gangplank, my newly-married great-great grandparents, Bernard and Sarah Donnelly, set out from County Leitrim in Ireland to join hundreds of other Irish immigrants on the New Zealand goldfields. My paternal grandfather, Charles Dinsdale, emigrated from Yorkshire, England in the early 1900s. By then steam had replaced sail, but he would have set out for his new life half-way across the world with the same sense of adventure.

In her book, Simpson tells of a shipboard fire, when passengers & crew took to the lifeboats. A woman passenger wrote that, when told of the fire, ‘I folded up my knitting, put on my bonnet and shawl, and went up.’ Simpson comments: “So figuratively hundreds of other women folded up their knitting, and, putting on bonnets and shawls, quietly faced these and other perils, and all the acute discomforts of the long voyage to the new land where their hopes rested. Dangers and discomforts were accepted without fuss.”

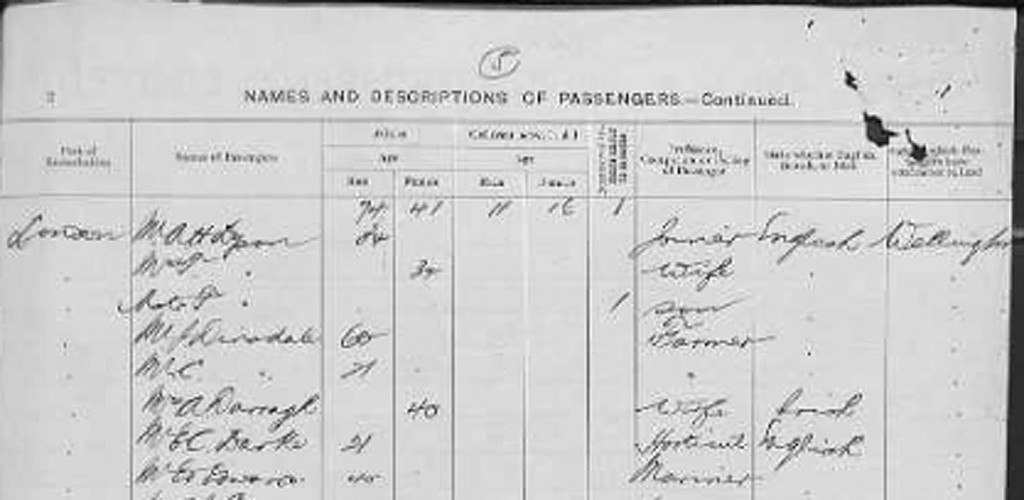

Passenger list for the SS “Corinthic” 1904. The 21-year-old C. Dinsdale (fifth name down) is probably my grandfather. From https://familysearch.org

Simpson’s standard of appropriate behavior is typical of the New Zealand society I grew up in, where we were expected to just deal with whatever hardships came our way. This is why I felt so chagrined for feeling sorry for myself.

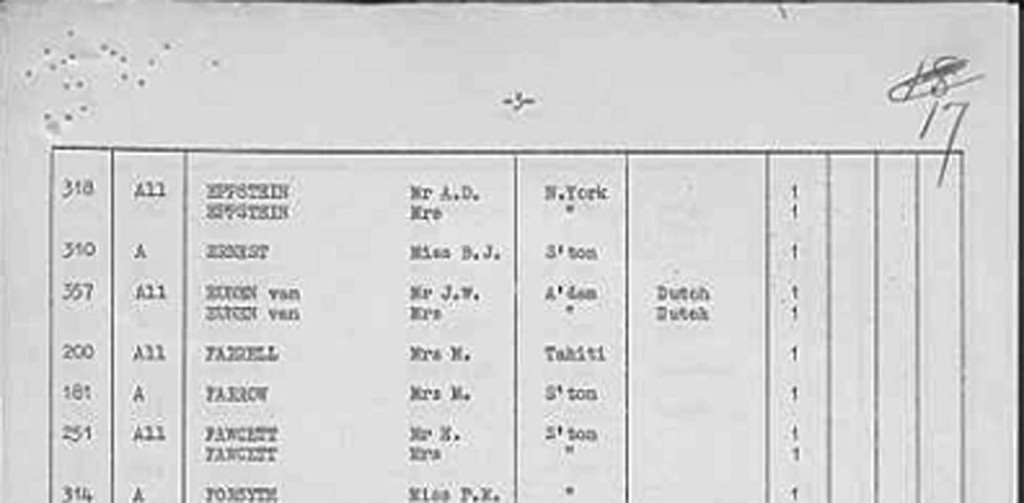

Passenger list for the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” 1962. Our names are at the top of the page. From https://familysearch.org

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

How I scooped the sports department

Chat with famous race car driver’s mother

Bruce McLaren in the 1969 German Grand Prix. Photo by Lothar Spurzem, via Wikimedia Commons

Getting the interview was easy. The mother of race car driver (and later designer) Bruce McLaren was my Great-Aunt Ruth, whom had known since I was a kid.

In January 1961 my cousin Bruce was back in New Zealand after an impressive debut on the Formula One circuit, where he had joined his mentor Jack Brabham on the Cooper racing team. In December of 1959, at the age of 22, he had become the youngest-ever winner of a Formula One race, capturing the U.S. Grand Prix at Sebring. He became a star overnight.

Here is a Pathé newsreel clip from that race.

The following year, Bruce came in second only to Brabham in the standings for the Formula One World Championship. Understandably, all New Zealand was agog.

Knowing via family that Auntie Ruth and Uncle Les planned to be in town to act as staff for Bruce as he worked the New Zealand racing circuit, I arranged to visit them at their hotel. Perched on the bed with our cups of tea, my aunt and I settled in for a cosy chat. Auntie Ruth was a great raconteur, and since I already knew the family history, it took little prompting on my part for her to re-tell her best stories.

The interview ran much longer than usual, but the editors at The Press published it in full. The day it was published, almost all the men from the sports department and the general reporting pool stopped by the women’s department to congratulate me. “How on earth did you get that interview?” the sports editor asked. I just smiled.

Bruce went on to establish Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Ltd. Unfortunately, in June 1970, he was killed while testing a McLaren CanAm car at his company’s site in England. His company lived on and today enjoys the reputation as one of the world’s foremost racing teams. Bruce was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall Of Fame in 1991.

I’ve appended a transcription of the interview with Great-Aunt Ruth.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

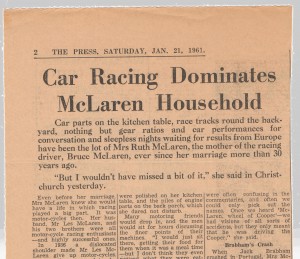

The Press, Saturday Jan 21, 1961

Car Racing Dominates McLaren Household

Car parts on the kitchen table, race tracks round the backyard, nothing but gear ratios and car performances for conversation and sleepless nights waiting for results from Europe have been the lot of Mrs Ruth McLaren, the mother of the racing driver Bruce McLaren, ever since her marriage more than 30 years ago.

“But I wouldn’t have missed a bit of it,” she said in Christchurch yesterday.

Even before her marriage, Mrs McLaren knew she would have a life in which racing played a big part. It was motor-cycles then. Her husband, Mr Les McLaren, and his two brothers were all motor-cycle racing enthusiasts – and highly successful ones.

In 1936 a dislocated should made Mr Les McLaren give up motor-cycles. Two or three years later he became interested in racing cars.

World War II ended all racing, but after the war Mr McLaren did a great deal of club work in hepolite trials and hill climbs.

Bruce, aged eight at the time, was interested even then, and two years year, when he entered Wilson Home with a hip disease, he insisted on regular reports from his father.

Muddy Clothes

After Bruce came out of the home, at the age of 12, he spent 12 months with a hip sling and crutches. Football was out, much to his disappointment, but Mrs McLaren still found her share of muddy clothes to wash when Bruce and his father went on hill climbs and mud trials.

Bruce’s first car was an Austin seven, which he acquired and “hotted up” at the age of 14. That was the end of Mrs McLaren’s garden. Too young for his driver’s licence, Bruce could not drive it on the roads, so he made a race track round the backyard and through the orchard. “No garden, and no branches left on the trees, either,” Mrs McLaren recalled.

Every visitor to their Remuera home was initiated to the track, and had to endure a hair-raising and head-ducking ride round the course.

From driving-licence age on there was a series of gymkhanas, hill climbs and mud trials, Mrs McLaren said. “It was a great thrill seeing him win—we used to go everywhere with him.”

Parts in Kitchen

When Bruce was 16 his father acquired an Austin Healey, which had something special about its engine. Although Mrs McLaren has picked up a great deal of motoring jargon, she cannot remember exactly what it was. All she remembers is the gloating and loving care with which the parts in question were polished on her kitchen table, and the piles of engine parts on the back porch, which she dared not disturb.

Many motoring friends would drop in, and the men would sit for hours discussing the finer points of their machines. “I would just sit there, getting their food for them when it was a meal time—but I don’t think they even noticed what they were eating,” said Mrs McLaren.

By this time both Bruce and his father were driving the Austin Healey. There came a day when the son drove it faster than the father. that was the day when the father decided it was about time he quit.

Waiting for News

The news that Bruce had won the driver-to-Europe award caused great excitement in the McLaren household. Later, when he had gone, came the terrific strain of waiting for results.

“I just lived on my nerves the week-ends he was racing,” said Mrs McLaren. Always at the back of her mind was the fear of a crash. “We have great faith in Bruce’s driving ability, but there are always things beyond his control. But he has not had an accident yet—touch wood.”

The McLarens waited anxiously for the first B.B.C. news in the morning, since the results of the championship races were always announced, and the news would come faster than a cable.

Visit to Europe

Two seasons ago, Mr and Mrs McLaren went to Europe and followed Bruce around the championship circuit. “We had a wonderful time—the racing fraternity accepted us as one of themselves, and looked after us wonderfully,” said Mrs McLaren.

During the races in New Zealand Mrs McLaren acts as lap scorer, but this was Mr McLaren’s job on the European tour. Mrs McLaren’s job was to stand by with wet towels and warm pullovers.

With the wives of drivers and team managers, she would go shopping and sightseeing in the towns of Europe. “Usually someone in the party would speak the language, which helped a lot,” she said.

Language difficulties often caused panics on the racing circuits. “The turns of phrase were often confusing in the commentaries, and often we could only pick out the names. Once we heard ‘McLaren, wheel of Cooper’—we had visions of all sorts of accidents, but they only meant that he was driving the Cooper,” she said.

Brabham’s Crash

When Jack Brabham crashed in Portugal, Mrs McLaren was with his wife Betty in the pits. “It was dreadful—it was only half-way through the race, and we had to wait till the end of the 72 laps to get across the track to find out whether he was all right.”

And the end they dashed across the track, jumped into Bruce’s car and to the hospital, where they found after much difficulty and confusion that Brabham was not hurt, but was being kept under observation.

On another occasion in France, when the temperature was 96 degrees in the shade, and 136 degrees on the race track, Bruce came into the pits after the race badly cut with flying stones.

Now Mr and Mrs McLaren wait through the year for the few crowded weeks when Bruce is home. “It makes up for all the time he is away,” said Mrs McLaren. The house is always full of drivers and friends, and is besieged by young autograph hunters.

“It’s very hectic, but very exciting. I wouldn’t miss it for anything,” said Mrs McLaren of her life as mother of a racing car driver.

I am thankful

I am thankful today for my new refrigerator. Our old one died a few weeks ago. Its replacement, a New Zealand-made Fisher & Paykel, was delayed by labor problems at the Los Angeles docks and eventually had to be unloaded in Vancouver and trucked down to Mendocino. Meanwhile Canclini’s, our local appliance dealer, gave us a smallish loaner, which has been parked out in the garage. We have gotten used to traipsing back and forth carrying milk or butter, and had set up ice chests on the back porch in preparation for an overflow of drinks and produce to feed our visiting family and friends during the Thanksgiving holiday.

It would be inconvenient, but we would cope. We’ve survived worse holiday crises. There was that time thirty-five years ago when we were remodeling an old house in Palo Alto. The kitchen walls were stripped down to the studs. Crates of new kitchen cabinets filled the living room, blocking access to the fireplace. I noted in my journal: At least I did warn [our friend] Judi that we might be picnicking amongst the mess. … [Our teenage sons] moved the kitchen cabinets today so that the sitting room & fireplace are usable again. Until the gas lines are reorganized, we have no heat, and the weather is getting colder, so it was important to be able to have a fire in the fireplace. We have plenty of firewood at least. On 11-30-1979 I noted that we had a delightful ‘old-fashioned’ Thanksgiving with Judi and her son Mark, who had been friends with our sons since they were little boys.

Thanksgiving a year later, the second floor completely rebuilt, we were waiting for the new roof to be completed and keeping a wary eye on the weather.

Journal 11-24-1980: The disaster finally happened over the weekend – eight weeks good luck couldn’t last. It rained Friday evening. Trusting in the plywood sheathing, we didn’t cover the floor with plastic all that thoroughly – a mistake. Throughout the night new drips opened up in the ceiling, mainly in the places where old plaster joined with new or at best was sagging or cracked. Buckets and towels all over the floor. We had to move out our bed because of a drip above us, which turned into a downpour slightly further along the crack about 3:00 am. David’s room also, where old gable met new roof, had a line of drips. Nasty watermark on the ceiling (most of which we were going to redo anyway). No permanent damage to floor. Spent all Sat. cleaning up in preparation for Thanksgiving, which I suspect is going to be as improvised as it was last year, though in different ways. Kitchen is finished, though with temporary lighting (as is all of ground floor). Can’t use the fireplace – need extension flue, which is still being built. Will have to decorate at eye level, prevent people’s eyes from moving upward, because of water marks on ceiling and upper walls. Stairwell still a mess of lath and ladders.

We survived that Thanksgiving holiday too. But this year we had a last-minute rescue. The kind men from Canclini’s brought us the new fridge on Wednesday morning and also left us the loaner until after the weekend, just in case we needed extra space. The turkey sits there now. In a little while, I’ll head out to the garage one more time and bring it in to the oven.

Thank you, Canclini TV & Appliances, and Happy Thanksgiving everyone.

The Doll

As a child, I was a trial to my mother. Throw epithets at me and I’ll own them: mean, resentful, difficult. I was jealous of my sister Evelyn, one year older than me. She was the beautiful one, with the blue eyes and golden ringlets my mother adored, the one with the heirloom china doll with its own blue eyes and golden hair, handed down from some relative or other.

Another word: ungrateful. That describes me this week, when an email from my youngest sister Alison arrived. She and my other sister, Patricia, had been doing a spot of spring-cleaning and had found my childhood doll. Did I want it? No, I replied, flooded with guilt about that unloved “child.”

A memory. I am maybe five or six. I am lying on my parents’ bed, sobbing and sobbing. I have been put there on time out for fighting with my cousin. Lee was a few months younger than me. She was then an only child, with parents who doted on her. Lee had a fancy new baby doll. Evelyn had the exquisite china doll. We played mothers and babies, but all I had for a baby was a yellow knitted creature of indeterminate parentage. I picked a fight. Lee and I came to blows. Time out. I sobbed at being hauled in from play, at the unfairness of life.

The door opens and Lee creeps in.

“What do you want?” Surly, still angry.

“I know a secret. You’re not supposed to know. Your Dad’s fixing Sally.” Sally was another heirloom, a celluloid baby doll so fragile she was constantly on Dad’s workbench with a broken limb.

An adult arm reaches through the half-open door and drags Lee out. It gives me satisfaction to hear her being slapped and scolded. A few minutes later my mother appears. “You might was well come out, then. It was supposed to be a surprise.”

Dad’s repair to Sally lasts no longer than usual. But at least I have a glimmer that someone cares. For my birthday I receive a large package from my parents. It is a doll who can close her eyes in sleep. But not a beautiful doll. She looks like me: straight dark hair cut into bangs like mine, brown eyes, a tiny mouth, her features molded in some coarse composition material. I play with her, of course, but do not cherish her.

Seventy years later, the doll’s portrait shows up in my email in-box. Where on earth has she been all these years, I ask my sisters. It turns out they found her among the effects of our eldest sister, Evelyn, who died several years ago. Had Evelyn kept her safe all these years? Or had she rescued her from our mother’s cluttered house when she helped move Mum into an assisted living apartment? We’ll never know. But it humbles me to think that both of them cared enough to keep the doll safe when her oblivious “mother” abandoned her.

The doll is now officially an antique, sister Pat tells me. She’s somewhat the worse for wear. Her hair is gone. It looks like she’s fallen on her face a few times. I feel a rush of tenderness for the forlorn creature she has become. I’ve asked my sisters to find her a good home.

Transience

The print that hangs on my study wall is old now, as I am. When I look at it I remember seeing the original painting, Georges Rouault’s “The Old King,” in London in the early 1960s. It was on loan from the Carnegie Museum of Art, part of some big exhibition. The Tate or the National Gallery, I don’t remember which. A crowd of viewers. The friends I was with moved on to other rooms in the gallery. I stood rooted in front of the picture, tears streaming down my face. Read the rest of this entry »

Ending a Story

I’ve just posted a piece on the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference blog about working with my editor, Andrew Todhunter, on revisions to my memoir about my sister Evelyn. The draft is finished, and out once again for comments. It’s always so valuable to see one’s work through another’s eyes.

Now I’ll need to write an epilogue. Just this week we learned that the New Zealand Geographical Board has assigned the name Stokes Peak, in Evelyn’s honor, to a peak in the Kaimai Range, between Tauranga (where she was born) and the Waikato (where she lived and worked). An impressive end to the story.

Mother and Child

My new great-niece came to visit this week. At ten weeks old, Baby Jessica smiles and gurgles. “Being a mother is different from what I expected, my niece Angela says. “I thought I’d spend all my time looking after a helpless baby. I didn’t realize I’d be getting to know a little person.”

I watch the two of them as they gaze into each other’s eyes, and am overwhelmed by the miracle of that mother-child bond.