Archive for the ‘Music’ Category

The place of art

What is art, and what place has it had in my life? This was the assigned topic for the first set of high school student essays I graded in my first paying job in California. In those days, the late 1960s, California schools had enough money to hire readers to relieve teachers of the time-consuming task of grading papers. I worked primarily with Millicent Rutherford, the Humanities teacher at Lynbrook High School, in the Cupertino Union School District. Over time, we developed a warm friendship.

I was saddened to learn that Millicent died last October, at the age of 91. Her obituary notes: “She will be remembered for her glittering sense of style, her sharp wit, and her boundless energy.” A 1991 Los Angeles Times article on remembering teachers who made a difference includes an anecdote by Stephen Bennett, CEO of AIDS Project Los Angeles:

“We’d study Italian art and [Ms Rutherford] would get . . . photographs from some of the Pompeian paintings that are not typically looked at—the parts of Pompeii they won’t show you because the graphics on the wall are what Americans would consider lewd. And she’d show up in a Pompeian red dress to start the day.”

To honor Millicent’s memory, I’ve been thinking about how I might respond to her essay topic.

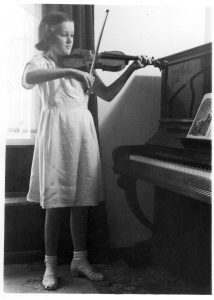

When I was the age of Millicent’s students, music was my passion. I played second violin in my town’s municipal orchestra. At my first concert, the orchestra tackled Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. It must have sounded decidedly amateurish. But the experience of being a part of that magnificent work, of sharing the language of music with my fellow musicians and with an audience, is a thrill that has always stayed with me.

Tauranga Municipal Orchestra at rehearsal in the high school assembly hall, c. 1952. I am in the front row, just to the left of the podium.

Painting too speaks a language without words. On the wall of my office is a reproduction of Georges Rouault’s “The Old King.” I saw the original fifty years ago, at the National Gallery in London. Friends I had come with moved to another room without me as I sat on a gallery bench, weeping. I still weep inside when I look at it.

Concerts, theatre, dance performances and visits to art galleries have always been a major part of my life. The written word has been my personal art form. To struggle with the lines of a poem, to convey emotional meaning through images, leads me to a personal answer to the question: “What is art?” For me, it is a way of sharing what is meaningful in our lives.

All a poet can do is warn

All a poet can do today is warn.

–Wilfred Owen

Cream plastic transistor radio close to my ear, I sat by the window of our London bedsitter, hearing familiar words set to brand new music: the premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem”. The May 30, 1962 performance was part of a festival to mark the consecration of St Michaels Cathedral in Coventry, a new modern building set alongside the bombed-out ruins of the old.

I had a personal interest in the cathedral, since one of my assignments for my New Zealand newspaper had been to interview the glass engraver John Hutton, one of the many eminent artists whose work graced the new building.

I was also caught up in the prevailing excitement about the completion of this significant architectural and spiritual project. Contained within the walls of the new cathedral was the idea of reconciliation, that it would be a place that would, in the words of the cathedral website, play a part in

Healing the Wounds of History

Learning to Live with Difference and to Celebrate Diversity

Building a Culture of Peace

But mostly my interest was in the poetry of this new musical work. I had been introduced to the poems of Wilfred Owen in high school. A soldier who died on the battlefield in the last week of the first World War, he wrote searing indictments of that war’s ravages. To me as a student, it was a revelation that poetry could be used to express such pain and anger.

I already had some familiarity with Britten’s music, but I was blown away by the “War Requiem”, which interweaves Owen’s poems with the traditional Latin of the requiem mass. I was brought to tears by Britten’s handling of Owen’s poem of reconciliation, “Strange Meeting,” in the concluding section of the work. In the poem, Owen imagines two dead soldiers, one English, one German, who meet each other

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined

They share life stories:

Whatever hope is yours,

Was my life also; I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world

…

I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled

…

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

The poem ends with the line Let us sleep now … which Britten repeats and extends in a hypnotically murmuring lullaby.

I have listen to the “War Requiem” many times since that memorable evening in London. It still brings me to tears.

A 1963 audio CD of the War Requiem, featuring the soloists for whom it was written, Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Galina Vishnevskaya, is available on Amazon.

A 1963 audio CD of the War Requiem, featuring the soloists for whom it was written, Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Galina Vishnevskaya, is available on Amazon.

The Poetry Foundation website has a good selection of Wilfred Owen’s poems.

Great music stays in the mind

I fell in love with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau when as a college student I heard his glorious baritone caress Schubert lieder in Christchurch’s boxy old Town Hall. I fell in love again when Mstislav Rostropovitch strode onto the same stage and plunged immediately into a Brahms cello sonata.

I fell in love with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau when as a college student I heard his glorious baritone caress Schubert lieder in Christchurch’s boxy old Town Hall. I fell in love again when Mstislav Rostropovitch strode onto the same stage and plunged immediately into a Brahms cello sonata.

From an early age, music has been an important part of my life. At the age of thirteen I was playing second violin in my home town’s municipal orchestra. We weren’t very good, but we were ambitious; the major work of my first concert was Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

In Christchurch I played in the Canterbury University orchestra, and discovered the joys of playing Bach as an ensemble, of listening for the counterpoint of continuo and chorus in one of his great chorales.

I never seriously considered a career in music, but have continued to be an enthusiastic listener, going to as many concerts at budget allows. So it was with great excitement that my husband Tony and I explored London’s musical offerings when we arrived in 1962. Re-reading the letters to parents saved in my old black filing cabinet, I see that nearly every one contains mention of some musical event.

April 9

[At Westminster Abbey] While we were there a choir and orchestra were having a final rehearsal of Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion.”

April 28

On Good Friday we attended a performance in the Royal Festival Hall of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion by the London Choral Society. … We went there again on Wednesday evening for an all-Mozart concert, and we were sitting in the choir seats behind the orchestra – a favourite place for music students, as you get a wonderful view of the conductor, and feel right in the orchestra.

May 9

Last night we went to the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden – doesn’t that make your mouth water? It started off with a few divertimenti – rather pretty and fluffy, and the a very fine performance of “Les Sylphides” with the Russian dancer Nureyev stealing the show – you remember he defected from Russia some time ago. But the reason we went was for Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” – tremendously exciting, jagged and violent. In spite of the narrow benches in the gods, where you knees dug into your neighbour’s back, it was a great thrill to be there. Covent Garden seems to be a place for the dedicated ballet enthusiast – you rarely hear an audience go quite so crazy at other forms of entertainment. Outside the opera house is fruit market – it was quiet at night, but the smell of fruit was everywhere, and we walked down through the trucks and piles of cases back to the Strand.

May 25

Went to Bertrand Russells’ birthday party last Saturday, in the Festival Hall. Concert by the London Symphony Orchestra – one of the finest performances of Mozart’s 39th Symphony that I have ever heard. Also Lili Kraus in a very impressive performance of a Mozart piano concerto. Lots of speeches etc. too – made us realise what an outstanding leader Russell is.

The music comes back to me as I re-read my letters, and I recall what a wealth of culture London had to offer.

Music of the Elysian Fields

Growing up in New Zealand, the Metropolitan Opera House in New York was the stuff of dreams: the tragic drama of the opera plots, the names of the great stars, the LP disks in my mother’s collection played over and over. To actually be there was an extraordinary sensation. “The whole place just breathes atmosphere,” I wrote to my parents, “the opulent decorations of a former era, and the shades of the singers who rose to fame on its stage – portraits of the greatest everywhere. “

Thursday, March 29, 1962 was our last night in New York before my husband Tony and I took ship for England to continue our youthful adventures. My sister Evelyn treated us to the opera tickets as a grand finale to our visit with her. The performance that evening was Gluck’s “Orfeo ed Euridice,” a very quiet, 18th century version of the story, with a happy ending. To quote from the Metropolitan Opera synopsis:

“Overcome with grief and remorse, the poet cries that life has no meaning for him without Euridice (“Che farò senza Euridice?”). Preparing to take his own life, he resolves to join his wife in death. Before he can do so Amor appears and announces that Orfeo has passed the tests of faith and constancy and restores Euridice to life. The happy couple returns to the upper world, where they are greeted by friends, who perform dances of celebration. Orfeo, Amor and Euridice praise the power of love.”

What stays in my memory is the dancing. As I wrote to my parents: “The ballets, particularly in the scene in the Elysian Fields, are really beautiful. I think it is the ballets that really make the opera – the terrific contrast between this scene and the previous one – the Furies at the entrance to Hades – all dressed in torn black tights, writhing and twisting, outlined against eerie red flames.”

Here is a YouTube recording of Gluck’s Elysian Fields ballet music.

If you’d like to learn more about the performers, here is a page from Opera News, March 10, 1962

I also found this March 1962 review by Irving Kolodin in the Saturday Review:

“On the whole, the visual aspects of this ‘Orfeo’ were more absorbing than the aural, for Harry Homer’s settings (of 1938) still provide an atmospheric frame for the action and Violette Verdy (a replacement for the absent Alicia Markova) is an excellent dancer, as is Arthur Mitchell, who shared the place of prominence with her. John Taras designed the choreography, which was theatrically justifying if somewhat showy, in its lifts and leaps, for the repose of the Elysian Fields.”

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Encountering Carnival in Panama

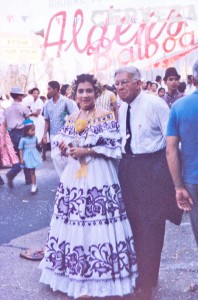

Panama City, March 1962

I had no idea that we’d arrive in Panama during Carnival. Even as our ship sidled into port at the end of the Pacific crossing, we could hear the sounds of it, the ramshackle city pulsing to a beat like none I’d ever heard. Once docked and allowed to disembark, we passengers pushed our way through dense crowds of people, among which wove decorated floats, costumed dancers, bands crowded onto the beds of battered trucks, men on the street beating drums or, lacking drums, the metal sides of the trucks, all singing and shouting to the heady Latin American rhythms. Sometimes a figure in fantastic costume would pass, surrounded by a group of friends singing and shouting together.

Everyone dresses up for Carnival. I was fascinated to see women wearing the pollera, the Panamanian national costume. Spanish in origin and atmosphere, the dress is of white cambric, embroidered in a bold floral pattern in a contrasting color, usually red, black or blue, each frill trimmed with a border of hand-made lace.

At roadside stalls we watched Panamanian boys scrape blocks of ice for the local sweet. They pressed the ice shavings into a paper cup, and poured over it a bright colored syrup and condensed milk. A bit tasteless, but very refreshing.

Passengers had been warned before we disembarked about the level of crime on Panama’s streets. There’s a hint of bravado in my letter to parents: “You just didn’t go into the side streets, or you would be unlikely to come back alive. Pickpockets everywhere. We were either lucky or careful (or both) but many of the passengers had purses, wallets or cameras stolen.”

What I didn’t write about was the effect on me of the incessant drums, the shouts and snatches of tune, the rhythm syncopated, hypnotic. I wanted to drown in it, swirl with the dancers forever into the glittering ocean of color and sound. But like the hawsers holding the ship to the dock, my past tethered me: syrupy fifties songs about marriage and children, strictures on proper behavior, appropriate dress. We wandered in the crowd for a day, then moved on.

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

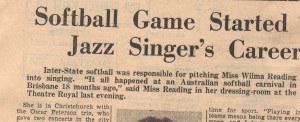

Backstage with Wilma Reading

When Wilma Reading and I stood in the wings watching the Oscar Peterson Trio perform in Christchurch’s Theatre Royal on January 31, 1961, we were two very young women over-awed by the glamour of our situations. Being backstage as a newspaper reporter was new to me: the blazing lights and deep shadows, the flats with their hanging ropes, the smell of dust, the stagehand snapping at us to keep our voices down. For Wilma it was the experience of being abroad for the first time, and performing with world-famous musicians. “I was scared when I knew I was coming. I am still scared when I go on to the stage. But I guess it will always be like that.”

When Wilma Reading and I stood in the wings watching the Oscar Peterson Trio perform in Christchurch’s Theatre Royal on January 31, 1961, we were two very young women over-awed by the glamour of our situations. Being backstage as a newspaper reporter was new to me: the blazing lights and deep shadows, the flats with their hanging ropes, the smell of dust, the stagehand snapping at us to keep our voices down. For Wilma it was the experience of being abroad for the first time, and performing with world-famous musicians. “I was scared when I knew I was coming. I am still scared when I go on to the stage. But I guess it will always be like that.”

Here is a 1961 audio clip of the great Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson and his trio.

Only eighteen months previously, Wilma Reading was a typist in an office in Cairns, North Queensland, Australia who played softball, hockey and basketball in her leisure time. She made the State team for a big softball carnival held in Brisbane. “On the last evening of the carnival, the softball teams had a get-together in a coffee lounge. Someone persuaded me to get up and sing for them, to add to the fun.”

Only eighteen months previously, Wilma Reading was a typist in an office in Cairns, North Queensland, Australia who played softball, hockey and basketball in her leisure time. She made the State team for a big softball carnival held in Brisbane. “On the last evening of the carnival, the softball teams had a get-together in a coffee lounge. Someone persuaded me to get up and sing for them, to add to the fun.”

Among the patrons of the lounge that evening was the leader of a Brisbane jazz band, who invited her to come and sing for the band. “I had to go home and talk it over with my parents, and they let me go.”

Engagements at a Brisbane hotel led to others in nightspots in the city. Later she went to Sydney, where she signed a five-year contract with a recording company. They are all popular songs. “I prefer jazz, but the company prefers popular tunes, as they sell better.”

In this 1960 video, Reading sings one of the currently popular tunes, “My Little Corner of the World”

Wilma Reading sings “My Little Corner of the World”

Future plans were a little vague, she told me. “I don’t think I could go back to being a typist, although I guess I could if I had to.” America and perhaps Hollywood figured fairly prominently in her dreams. “Still, there’s plenty of time and I have a long way to go.”

Wilma Reading went on to a 40-year career performing with major jazz musicians and on television. She was the first Australian to appear on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, had a residency at New York City’s Copacabana nightclub, and toured with Duke Ellington.

There’s a long and fascinating transcript of a TV interview with her at

http://www.abc.net.au/tv/messagestick/stories/s3224613.htm

As we stood in the wings that January 1961 evening, she confided that her main worry was how she would get on with the famous Oscar Peterson Trio. “Many musicians have no time for vocalists, but I have found them wonderfully kind and helpful. They are very natural and friendly, and very good to work with. They have given me a lot more confidence than I had before. Aren’t they amazing?” she whispered as the three imposingly large black men pulled sweet sounds from piano, bass and drums.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Words and Music from an Inner Garden

For more than forty years, my friend Diana Neutze has endured the relentless thefts of multiple sclerosis and grief for a son lost too young. Throughout that time, she has continued to write powerful and moving poems. Recently, her body closing down, she commissioned the New Zealand composer Anthony Ritchie to set some of her poems to music. The cycle of seven songs, “Thoughts from an Inner Garden” premiered April 2011 in a performance at Diana’s house in Christchurch, New Zealand. Diana recently sent me a CD of that performance. I’ve been playing it over and over, overwhelmed by the beauty and intensity of the work.

From Diana Neutze’s published collections, A ROUTINE DAY and UNWINDING THE LABYRINTH, Ritchie selected poems that express the poignancy of the poet’s sense of connection with the tangled garden that surrounds her house, a garden that has become her world. Transcending the nightmare of her chronic illness, she finds meaning in the details of the natural world: the play of light and shadow, the song of a bird.

The cycle opens in a minor key, an ancient, timeless sound that describes a day of wet greyness without wind when the garden is holding its breath. In “Bridal,” the second song, the poet, showered by autumn gold, imagines the roses and smoke bush as witnesses to a marriage between herself and the garden. The mood changes in “Chronic,” where Ritchie’s urgent rhythm reflects the tick-tocking of illness/ relentlessly. “And the Birds Sing” is a meditation on the cycles of life and death. “A Scent of Water” offers a fragile hope in the face of grief: a frosting of growth/ a shivering of buds in the morning light. The rhythms of an old folk dance come to mind in “Meaning.” A moment in late afternoon, a blackbird singing in a weeping elm, and the day is flooded with meaning. The cycle closes with “Goodbye.” The poet recalls the garden images she will die loving. The theme of a Bach partita enters the music as she describes its architectural splendour … arch after musical arch soaring upwards.