Archive for the ‘birds’ Category

A tale of a sparrow

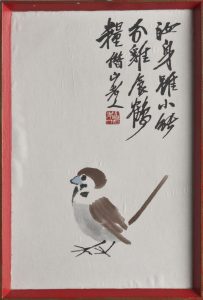

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

14 April 1969

A friend of Tony’s from Memorex came to dinner. A Korean boy … He is really charming, and we had a pleasant evening. One interesting thing that came out of it – Yun also reads and writes Mandarin Chinese, so was able to translate the inscription on our sparrow picture for us. Do you remember our sparrow? It is a little brush drawing that Tony picked up in a junk shop in Hawera when he was a student, shortly before reading in a magazine a story about a famous Chinese artist who was objecting to a government campaign to kill off the sparrows to improve the wheat production. He made these little posters, inscribed with sentimental stories about the sparrow. And this, as far as we can tell, is what we have got.

With the help of the Internet, I’ve been piecing together my fragments of knowledge about this period in Chinese history. What I discovered is a familiar story about well-intentioned interference with nature leading to ecological disaster.

In the First Five-Year Plan of the newly-founded People’s Republic of China, families were each given their own plot of land. In the Second Five Year Plan, begun in 1958, a new agriculture system was announced. Family farms were grouped into collective farms, making each village a single production entity in which everyone would have an equal share. Food would be provided in a communal kitchen.

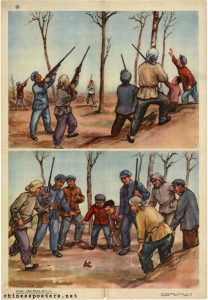

In theory, a collective farm where resources were centrally controlled should be more efficient and yield higher productivity. In practice, agricultural production figures fell. Food shortages were exacerbated by flood and drought. Believing that getting rid of sparrows, who ate grain, would improve production, Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Four Pests Campaign, which encouraged citizens to kill them, along with three other pests: rats, flies, and mosquitoes. Sparrow nests were destroyed, eggs were broken, and chicks were killed. Many sparrows died from exhaustion; citizens would bang pots and pans so that sparrows would not have the chance to rest on tree branches and would fall dead from the sky. Citizens also shot the birds down from the sky. These mass attacks pushed the sparrow population to near extinction.

In hindsight, the result was inevitable. Too late, Chinese leaders realized that sparrows didn’t only eat grain seeds. They also ate insects. With no birds to control them, insect populations boomed. Locusts, in particular, swarmed over the country, eating everything they could find, including crops intended for human food. People, on the other hand, quickly ran out of things to eat, and tens of millions starved.

Robin redbreast on a fence

I still ponder why it meant so much, that Christmas morning in England in the 1960s, that a robin sat on the back fence. The field behind the fence was white, the fence wires thick with hoar frost, and the little red-breasted bird made the scene perfect. Finally, I told myself, a ‘real’ Christmas.

I have tried for many years to clarify my feelings about the disconnect between the traditional trappings of the season and my experience of growing up in New Zealand, where the seasons are reversed. My childhood Christmas memories are of summer: the tree laden with oranges in my grandmother’s garden where we hung our presents and picnicked on the lawn; the scent of magnolia blossom outside the church on Christmas Eve.

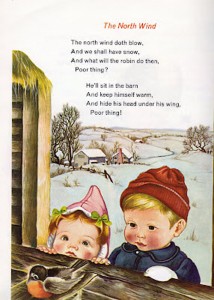

Also the Christmas cards with their images of snow (which I’d never experienced) and yes, the English robin. I knew about robin redbreast from the old nursery rhyme, but until that Christmas I hadn’t seen one.

Now on the coast of Northern California, I have a different understanding of how to celebrate the winter season. Our multicultural society recognizes many winter festival stories and traditions: the birth of Jesus in a stable, the menorah candles of Hannukah, the Swedish light-bringer St. Lucia, the gift-bringer St. Nicholas (known also as Santa Claus), and many others. The celebration that holds the deepest meaning for me now is Winter Solstice, the return of the light. From summer to winter, I note where on the horizon the sun sets, and how the darkness grows. Even as clouds gather, the place where sun disappears into ocean fogbank moves steadily to the south. When the prevailing westerly wind shifts to the southeast, I know to expect the winter rains. Sometimes a shower or two, sometimes, such as this past week, a prolonged deluge that floods rivers, downs power lines, and closes roads.

Meanwhile, the earliest spring flowers are breaking bud, and over-wintering birds gather hungrily at my feeder: Steller’s jay, spotted towhee, hermit thrush, acorn woodpecker, hordes of white-crowned sparrows. I love them dearly. I am happy that I have learned to understand the connection between the flow of seasons and human efforts to explain them with stories and festivals. And I still have a place in my heart for the memory of that cheery robin redbreast who brightened an English winter.

Ducks and swans and boats, oh my!

My son’s first word was “duck.” This is not surprising. We lived in Windsor, England, downhill from Windsor Castle and a few blocks from the River Thames, a destination for our daily walk.

There was always something to see on the river. Sometimes rowing crews from Eton College, eight oarsmen in a long narrow shell sweeping the water with long strokes, the cox calling the rhythm. Lots of boats. My family’s special favorite was the elegant “Esperanza,” one of the many riverboats that took visitors on trips upriver.

David’s favorites were the ducks. There were hundreds of them on the river, dabbling among the water weeds, bobbing under with their tails in the air, or clustered enthusiastically close to the walkway if we remembered to bring stale bread to throw to them.

The swans were more scary. They were big, and their large beaks looked ready to take a nip if they were feeling feisty.

The swans of course are famous. Some of the mute swans on the Thames belong to the Queen, others to two ancient guilds, the Vintners and the Dyers. Each year, toward the end of July, there occurs a ceremony called Swan Upping, during which Thames swans with cygnets are rounded up by official Swan Uppers, caught, checked for health, marked with the appropriate leg rings, and then released under the direction of the Swan Marker.

Swan Upper with swan. Photo by Bill Tyne, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29175336

Every day, something new to see.

My first cuckoo

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu

Listen to this Medieval rote song

An English oak woodland. Image from Open University on the BBC

My first spring in England, late afternoon in Windsor Great Park. Green-gold light through ancient oaks, the air rich with leaf-mold and violets. A cuckoo calls. I have heard the sound all my life, in music and poems, but never before in the wild.

Listen to the cuckoo calling in this recording from the British Library

As I stand listening, this spring in 1962, something shifts in my thinking. It is as if previously I saw the world through two mesh screens, one named Southern Hemisphere and the other Northern Hemisphere, half a year out of alignment with each other, so that my view was blurred by the moiré patterns their meshes made. The religious festivals my ancestors brought from the northern hemisphere when they emigrated to New Zealand lost their old association with the seasonal cycles of life and death when celebrated in the reversed seasons of the southern hemisphere. In consequence, I felt, even as a child, a subtle sense of having been cut off at the roots, of being, even after several generations, transplanted British.

Images float into my mind. Mid-morning, Christmas Eve, at All Saints Church in Tauranga, NZ. Strewn mounds of flowers deck the chancel steps. The Altar Guild ladies are filling shiny brass vases that stand either side of a red-draped altar. Bronze-purple foliage of copper beech, fans of gladiolus spikes, the tropical exuberance of canna. They add dahlias, roses, bougainvillea until the reds vibrate.

Sunlight through stained glass glitters on the sharp points of holly springs that I strew along the dark wood windowsills, hiding jam jars filled with red geranium flowers. The holly bears no berry here, this time of year, and the carol I hum under my breath echoes in an empty place inside me. Later, at midnight services, the congregation sings of light in darkness and the falling of snow. We emerge to warm air, misty moonlight, and the scent of magnolias. This Christmas is not real, I think to myself. It’s pious make-believe.

Easter: after morning church and family lunch, I gather with siblings and cousins on the porch to smash the Easter eggs we have all been given. Molded of hard sugar, they are pastel pretty, with piped-on decorations of flowers and leaves, the symbols of spring. Having gorged ourselves, we scamper off to scuffle through autumnal leaves.

Cuckoo image from

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

My reading in college, particularly J.G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough, helped me recognize that Christian festivals have pagan roots: the ritual victim dies at planting time; the winter birth is the rebirth of the sun. As the cuckoo calls again, cu-coo, over and over, quietly, the blurred meshes of my hemispheres resolve and I see through: myself and my people bound by tangled apron strings to the life our forbears left, and to the earth itself, an old reality, almost forgotten.

A taonga returns home

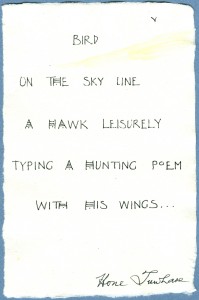

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

The manuscript is one my treasured possessions. I have pangs of regret about parting with it, but know I am doing the right thing. In New Zealand Tuwhare’s work is considered a taonga, a treasure. He was the first M?ori poet writing in English to win widespread acclaim. His best-known book, “No Ordinary Sun.” first published in 1964, was reprinted ten times over the next thirty years, becoming one of the most widely read individual collections of poetry in New Zealand history. The title poem is a response to French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Many more collections followed. His work has a conversational tone and incorporates both M?ori and biblical rhythms; the subjects range from the political to the personal and often powerfully evoke the beauties of nature. He won several New Zealand book awards, and was poet laureate of New Zealand in 1999–2000. He died in 2008, at the age of 85.

The M?ori concept of taonga also includes the story that goes along with the item. My little manuscript was a gift from Jean McCormack Tuwhare, Hone’s ex-wife. She and my mother-in-law were friends. On a visit to New Zealand in 2000, I spent a delightful afternoon with Jean at Mother’s house discussing poetry and literature. Mother had shown Jean my first poetry collection, “A Place Called Home,” and later suggested I send her a copy. Enclosed in Jean’s thank-you letter for the book was the Tuwhare manuscript. Unfortunately the letter is lost, but as I recall, Jean wrote that Hone (with whom she was still close friends) liked to practice calligraphy and had given her several of these small pieces to dispose of as she wished. She thought I might appreciate having one.

[Update 6/2/1016: While in New Zealand, I learned from Rob Tuwhare, Hone and Jean’s son, that Jean herself did the calligraphy, and Hone signed her work.]

I am of an age when I need to make decisions about my stuff. Knowing that the manuscript could easily get overlooked among our mountains of paper and art works, I sought professional help. I told Malcolm Moncrief-Spittle of Renaissance Books (New Zealand) , who deals in rare and out-of-print books, that I thought my taonga should be returned to New Zealand. Which university or cultural institution in New Zealand already houses a collection of Tuwhare material and would be a suitable recipient? I asked. He recommended the Hocken Library at the University of Otago in Dunedin.

Staff at the Hocken Library responded to my query with enthusiasm. We’ve arranged a meeting on May 9, when I will hand over the carefully packaged manuscript. I know it will be a happy/sad occasion.

The End of a Great White Ship

The memoirist Judith Barrington and I have a ship in common. Her memoir Lifesaving has at its center the cruise ship “Lakonia,” which departed Southampton on December 19, 1963, on a Christmas voyage to the Canary Islands. Three days later, a fire broke out. In the ensuing confusion and panic, a small group of passengers, including Judith’s parents, were left stranded without lifeboats and drowned.  Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

On February 13, 1962, the previous year, my husband Tony and I left New Zealand on that same ship. At the time her name was the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt,” of Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN), also known as the Netherland Line. It was not quite her last round-the-world voyage under this flag; the maritime historian Reuben Goossens notes that her final departure from Wellington, NZ was in January 1963.

“What was it like on board?” Judith asked me. “I know my parents were on a cruise ship, but I can’t get a picture in my head of those staterooms or of being on that deck.”

I told her as best I could of the richly carved dark wood paneling that decorated the staircases and staterooms. Reuben Goossens notes that the décor was the work of famed Dutch artist Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945) and sculptor Lambertus Zijl (1866-1947). Lion Cachet “took a great delight in using some of the most exotic timbers and then mixing them with a range of materials, from marble, polished shell to tin and other unique materials. Décor throughout the ship reflected the colonial links between the Netherlands with the Far East.” Lambertus Zijl created many fine sculptures and reliefs that were to be found throughout the ship.

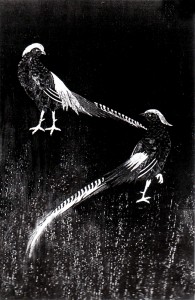

Cover of a JVO dinner menu. We collected and framed several of these, each showing a different bird.

Tony and I also had the sense of being on a ship with a long history. The JVO, as we lovingly called her, was launched in 1929, and was one of the most luxurious ships to be placed on the international trade route to the Dutch East Indies. She was requisitioned as a troop ship during world War II. After the war, she brought large numbers of British and Dutch immigrants to New Zealand under a government-sponsored program that provided free or assisted passages.

Refitted as a one-class cruise ship in the late 1950s, the JVO offered round-the-world and trans-Tasman cruises. Competition from airlines was by then reducing the demand for ships as a standard mode of passenger transport across seas, though airfares were still way beyond the means of most young New Zealanders. We obtained a lower level berth on the JVO for about $160 each. According to a 1963 Pan Am schedule an airline ticket from Auckland to London would have cost about $900.

So the JVO was sold in March 1963 to the Greek Line, and renamed the “Lakonia.” The cruise on which Judith Barrington’s parents perished was her maiden voyage under her new flag.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Requiem for a Great Horned Owl

A warm late summer afternoon at Stanford University. I’d found a shady grove to sit and eat my lunchtime sandwich. As I strolled back to my office in Encina Hall, the administration building, I noticed several co-workers clustered under the huge live oak in front of the building, hugging each other and gazing at something on the ground. Uneasy, I hurried to join them. The looks on my friends’ faces confirmed my fears. ”Our” Great Horned Owl, who regularly roosted in the oak, lay crumpled on the ground. Read the rest of this entry »

Juncos

A flock of twenty to thirty Oregon Juncos around the house yesterday, the most I’ve ever seen together. Such handsome, busy little birds. It gives me pleasure to know that the habitat we’ve created provides sustenance.

Quail Update

After I disturbed a quail on her nest in the walled garden in back of my house, I kept the gate closed for three weeks, which I learned was the typical incubation period for quail chicks. This morning I crept in, anxious about what I might find. I eased back a branch of thimbleberry, and cautiously lifted the thatch of dry blue-eyed grass. I glimpsed the rounded shape of an egg. Oh no, had the nest been abandoned? I looked closer. There were empty eggshells aplenty, neatly halved and stacked together in the grass-lined bowl of the nest. Eight or nine chicks have hatched and headed out into the big world. I’ve not yet seen them, though I’ve heard parental burblings from the bush-covered hill above the wall. Bon aventure, little ones.

I also had a chance to study the eggshells more closely, and realize I was mistaken in their color. They have a bluish cast, but the color is more of a creamy tan, speckled with brown blotches.

Nesting Time

An excellent excuse yesterday to give up weeding an overgrown part of my garden. As I reached for a dandelion, a hen quail scurried from the vegetation just inches from my hand. She stopped a few feet away, chirping her displeasure. I apologized for disturbing her, but to no avail. She fled to the thicket up the hill and raised a frantic alarm. Curious, I reached under a thimbleberry bush and lifted a soft handful of last year’s blue-eyed grass. Underneath was a nest filled with speckled green-blue quail eggs. It was a perfect site for a ground-nesting bird: a small, enclosed garden, the house on one side, a high retaining wall on the other, with fences at each end to deter predators. The nest was right up against the wall of the house, sheltered from spring rain by the house eaves, and from wind by the thimbleberry.

I gathered up kneeling pad, implement and weed bucket and retreated to the gate. Closing it quietly behind me, I kept watch from a distance. After a few minutes, the hubbub faded. The hen flew back to the top of the wall, accompanied by her cock. After a few more minutes of hesitation, she fluttered down to the nest.

Soon cute fluff balls will poke around among the ferns and violets and learn to scale the wall. The weeds can wait.