Archive for the ‘race relations’ Category

Saga of an unpublished novel

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a beat-up cardboard box that contains the dog-eared manuscript of my first completed novel in the US, “A Stone from the Wall.” The saga of my attempts to get it published, as reflected in letters to my parents, may get a nod of recognition from other aspiring writers.

March 15, 1972

I have finally got my book off my hands. I received an invitation last week to submit it to Houghton Mifflin Co., one of the most prestigious of the major publishing companies, so after a final frantic effort to finish typing the fair copy, it is now on its way. Whether they will buy it or not is of course another matter, but just to get an editor there enthusiastic about the idea is a tremendous boost. It is their sort of book—a serious look at a contemporary theme. My subject is racial prejudice, and the point I am trying to make is that, for a white person trying to come to terms with racial problems, the most difficult, and even painful, part is learning to recognize your own prejudices. This is mainly, of course, because the more concerned you become, the more you want to think of yourself as one of the good guys.

July 2, 1972

I was going to leave finishing this until after the mailman came today, but don’t really see the point. If I seem a bit edgy in this letter, I am. I was told by Random House that I would hear from them within 4-6 weeks. It is now nearly 5 weeks, and my heart starts hurting every time the mail truck goes up the road. It’s very tedious bracing yourself for rejection every day.

At some point I received a hand-written rejection note from the editor-in-chief of an eminent house—I believe it was Robert Gottlieb of Alfred A. Knopf—who complimented me on my “ability to make my characters come alive,” which buoyed me up for a few more rounds of submission and rejection. I no longer have the note or, for that matter, any of the many rejection notices I received.

July 25, 1972

My book showed up on the doorstep again, as expected. Disappointing of course, but this time I have decided to revise a lot of it before sending it out again. When you are writing fiction, you become in a very real sense the characters you are writing about, and sometimes it is difficult to stand back and look at them objectively—like it is difficult to look at yourself. But now I think I can see at least some areas where the characters are not interesting, or even not alive, but just vehicles for ideas. However, I am going to leave it now until fall—it’s just too difficult to work over the summer. The kids are very good, but they are something of a distraction. In the meantime I have various other articles and poems doing the rounds. They come back periodically, of course, but I figure that with enough things going, I’ll get somewhere eventually. I have had a couple of commissions from Tui [my editor at the Christchurch Press] which I have now sent off … I do still get very depressed every so often, but Tony usually manages to pull me out of it if I can’t shake it off myself. I even made a list this week of all the other things I was going to accomplish this summer. Boring jobs like cleaning the oven figure rather prominently …

November 1972

I am trying to get back to my novel, but keep getting sidetracked with new ideas [for stories and articles]. Have just finished grading a big set of students’ short stories for Millicent [the high school teacher for whom I worked]. Tremendous ideas and effort, but my main reaction as I tore each one apart was, my gosh, that’s what’s wrong with my writing too.

Discouraged, and preoccupied with other projects, I eventually gave up and moved on. As I noted in my blog essay “The Other Side of the Freeway,” I understand now why “A Stone from the Wall” never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject. I didn’t understand how much the life experiences, interests, and even musical tastes of my African-American characters might be different from those of my white characters. Though I devoured my subscription to The Writer magazine from cover to cover, the protocols of book publishing still felt like an enormous black hole. The battered manuscript box deservedly stays in the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet.

Community battles housing discrimination

In the early 1970s, my husband and I volunteered with Mid-Peninsula Citizens for Fair Housing. Here’s an article about the organization I wrote for my Christchurch, New Zealand paper.

FAIR HOUSING: A COMMUNITY APPROACH

Cupertino, CA, 1972

Discrimination in housing on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin has been illegal in the United States since 1968. But it is not so easy to legislate away prejudices so deeply ingrained that they are written into the textbooks of realtors and enshrined in the housing patterns of all our communities.

One group that has found this out the hard way is a San Francisco Peninsula organization called Mid-Peninsula Citizens for Fair Housing. Committed to the right of all persons to purchase or rent property wherever they choose, MCFH evolved in 1965 out of a nucleus of citizens who had fought an election proposition that would write in to the California constitution the right of the housing industry to perpetuate the existing discriminatory housing patterns.

The proposition passed, and MCFH learned its first lesson, that even in this allegedly liberal area, the housing market was tight shut.

Education, they concluded, was the key. By the time the federal Civil Rights Act of 1968 outlawed all measures like Proposition 14, MCFH had speakers visiting schools, factories and church meetings. Representatives started talking with local government officials and housing developers, focusing attention on the problems of housing for the aged, and other low income groups, as well as on racial minorities. A full-time lobbyist was employed to keep in touch with elected representatives in Sacramento, the state capital.

With the legal clout of the 1968 Act, they set up a legal aid service for members of minority groups discriminated against in obtaining housing. When a complaint is received, the Fair Housing Office sends out a White volunteer checker. In order to eliminate other legitimate grounds for a landlord to refuse an apartment, the checker matches the complainant as closely as possible, in everything except race.

The availability of the home, and the terms offered, are compared. If discrimination is apparent, MCFH offers the services of a volunteer lawyer, or assistance in filing a complaint with HUD.

But still this was not enough. Blacks and Chicanos, seeing the organization as yet another example of white liberal condescension, have been reluctant to contact the Fair Housing Office. On current showing it is affecting only one percent of the apartments in the area each year, and even fewer of the real estate sales. Meanwhile Peninsula communities are becoming more and more segregated, in terms of race, age, and economic status.

Now MCFH has added a new weapon to its arsenal. It is the community audit, a technique designed by Howard Lewis, a local realtor and vice-president of MCFH. The method used for an audit is much the same as that used to check individual complaints. The difference is that it is done by people already living in the neighborhood, who see their effort as a contribution to the community as a whole, and not to their individual housing needs.

Teams of checkers are made up: one White, one of a minority race. Most of the audits so far have been White/Black, but some White/Chicano audits are getting under way. One after the other the team members apply to their assigned apartments, and report back on the terms offered to them. The results are frequently double-checked, cautious MCFH lawyers preferring to give apartment managers the benefit of the doubt in dubious cases. But eventually a profile of the city’s housing practices emerges: in so many cases the Black was told that nothing was available, but the White was invited right in; in so many cases the rent quoted to the Black was higher, or the cleaning deposit was larger, or the credit check would take longer. The figures run between fifty percent and sixty percent for most of the varieties of discrimination, and the overall figure has been as high as seventy percent of the apartment units in any one city.

Reports are made to the individual apartment managers and owners, complimenting those who were shown to be obeying the law, seeking consultation with those who don’t. “The very least a fair housing organization can do,” says Fair Housing Director Marilyn Nyborg, “is contact housing industry members and talk with them—to deal with their fears, inform them of the law, and seek their commitment to equal opportunity in housing.”

The audits are repeated quarterly, and MCFH is prepared to take legal action against persistent offenders. But its members feel that local pressure is a more satisfactory incentive for obeying the law. For this reason the city council and the local press are also informed of the results of the survey.

Some city councils have reacted with suspicion and hostility; others have been spurred to initiate positive programs for their city’s housing needs. The City of Palo Alto, for instance, has set up meetings between discriminating apartment owners, representatives of MCFH, and its own Human Relations Commission; has agreed to act as co-plaintiff in discrimination cases; and has given notice, through a mailing to its utilities customers, that fair housing laws will be enforced in the city. Under discussion are ordinances that would provide for a public vacancy list; for the licensing of apartment managers; and for the use of written records of the terms offered to every prospective tenant. These stricter regulations are necessary, MCFH claims, because the education sessions they already provide for apartment managers have had little effect on their attitudes or practices.

We can influence the quality of life in our own communities, says MCFH. And change, though painfully slow, is happening. A few housing developers have publicly committed themselves to equal opportunity in housing. Some local realtors now display fair housing pledges in their windows. Membership of MCFH has swelled from the original handful of people to well over 2,000, and the annual operating budget, including contributions from local industries, is over $17,000. The organization is still a long way from its ultimate goal, equal justice for all in the housing market. But it is on its way.

The other side of the freeway

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a battered cardboard box containing the manuscript of a novel I wrote in the early 1970s. I understand now why it never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject: racial discrimination in housing. As I reread some of the text, I recalled the shock I felt when I first grasped the magnitude of the social gaps. The descriptions that follow come from my own experience as I researched the book, and it began my involvement with the fair housing movement.

Here is the central character Karen, a newspaper reporter, visiting the black ghetto of East Palo Alto for the first time to interview the director of a community advice center:

She knew vaguely that East Palo Alto belonged to the county. … She crossed the county line now, and accelerated to get onto the overpass that spanned the freeway. As she came down the ramp on the other side, she knew she was in a different country. The road was suddenly pot-holed and bumpy, and brown dust rose in thick choking swirls from its verges. She slowed, and looked about her. Such tiny bedraggled houses, desperately in need of paint. Yards littered with junk, yet here and there a brave attempt at order and color, a flower-bed, a well-cut lawn. She came upon a few tatty shops. Surely this couldn’t be the main shopping center? Yet soon she could see the sign, NAIROBI SHOPPING CENTER, and underneath, in a language she could not understand, UHURU NA UMOJA.

She had to force herself to open the door. Lurid accounts of rapes and muggings and violence in the streets flooded her mind. Here she was the enemy. She wanted to jump back into the car and get out, away from this place.

A woman passed, with two small children, headed for the market. She looked indifferently at Karen as she passed, then turned to scold one of the children, who was whining for candy. Karen let out the breath she had been involuntarily holding, and made herself move on. … Across the road, outside a liquor store, a black knot of middle-aged men stood transfixed in time, waiting for nothing.

It was hot. The dust lifted lazily as she walked. Something about the huge trees, and the stillness of the air, brought to her mind descriptions she had read of towns in the southern states. But this was California. It did not make sense. A mockingbird flashed its wings across her path, still proudly singing.

Karen does her interview, in which she learns about the pressures of living in East Palo Alto (and also finds herself attracted to Paul, the advice center director).

She said goodbye, and walked slowly back to the car, past the Louisiana Soul Food Kitchen and the Black and Tan Barber. The heat and dust were almost unbearable.

Back across the freeway, she noticed for the first time the neatly swinging redwood sign: Welcome to Palo Alto. A few blocks further down University Avenue and it hit her like a punch in the gut. She pulled over to the side of the road and rested her head on the steering wheel, fighting back an impulse to vomit. The contrast was an obscenity. Huge magnolias here lined the street on both sides, giving deep dappled shade to the well-paved highway. Between the road and the white concrete sidewalks rose great greening mounds of juniper and ivy, and beyond them, with manicured lawns and discreet sprinkler systems, were the complacent mansions of the rich.

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

What place have we come to?

I grew up in a country with strict gun control laws. In New Zealand in the 1940s and ‘50s, you needed a permit and a “proper and sufficient purpose” to acquire a firearm, and all weapons had to be licensed and registered. Automatic pistols were outlawed altogether. My dad kept a rifle in a locked closet, taking it out occasionally to go hunting for feral pigs with his friends. But guns were not part of my small town landscape. Even today, New Zealand police officers do not routinely carry firearms.

Imagine my state of mind then, when the newspapers of my newly adopted country ran daily news stories about firearm-related deaths. Looking back now at government statistics, I see that in 1968 the US, with a population of 200.7 million, had about 31,400 firearm deaths. (Since the Center for Disease Control bundled multiple years 1968-1980, this is an average.) CDC, in a 1994 report, predicted that people killed by firearms would by 2003 outnumber vehicle crash-related deaths. Louis Jacobson, in a PunditFact article, verifies Nicholas Kristof’s 2015 statement that “More Americans have died from guns in the United States since 1968 than on battlefields of all the wars in American history.”

On April 4, 1968, our family had been in the US less than a year. My husband Tony was in Washington, DC for an international magnetics conference. On March 30 I wrote to my parents: He is very excited about this, especially as he hopes to meet some of his friends from England who are expected there.

About a week later I wrote again:

10 April 1968

Tony also got involved last week in America’s other big trauma – the race riots following Dr. King’s assassination. He had great difficulty getting out of Washington on Friday [April 5], but fortunately the flight crew of his plane had the same problem, so managed to catch his correct flight a couple of hours late. I gather that the conference was very successful and useful, if somewhat exhausting.

Reading these words again today, I notice the calm, distancing tone. I couldn’t tell my parents that I was terrified. Tony had described to me the view from the night sky: cities in flames all across America.

Two months later, on June 5, 1968, presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy was fatally shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, shortly after winning the California presidential primaries in the 1968 election.

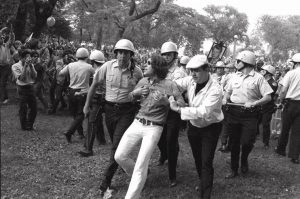

Police lead a demonstrator from Grant Park during demonstrations that disrupted the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August 1968. (AP) Image from https://www.washingtonpost.com/

Yet more public and political mayhem was to come. In August we endured reports of the violent clashes between police and protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. In its report Rights in Conflict (better known as the Walker Report), the Chicago Study Team that investigated the incident stated that the police response was characterized by:

…unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence on many occasions, particularly at night. That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat. These included peaceful demonstrators, onlookers, and large numbers of residents who were simply passing through, or happened to live in, the areas where confrontations were occurring.

I have to agree with Haynes Johnson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who was covering the convention. He wrote in a 2013 Smithsonian Magazine story that the convention was

…a lacerating event, a distillation of a year of heartbreak, assassinations, riots and a breakdown in law and order that made it seem as if the country were coming apart.