Archive for the ‘art’ Category

A family of potters

This story starts with a ceramic pot. But which one? Maybe the Lowerdown Pottery bowl I’ve treasured for over fifty years. Or maybe the piece that first inspired Bernard Leach, who is recognized as the “father of British studio pottery,” to take up the craft when he was invited in 1911 to a raku tea party in Japan. The story involves three generations of eminent potters: Bernard Leach, his son David Leach, and his grandson Simon Leach.

In June of 1964, Tony and I went on a vacation with friends to a village in Cornwall where we rented a house. In a letter to parents I wrote:

Yesterday we had quite a big trip – to St. Ives & Lands End. …Arrived at St. Ives in time for lunch – fish & chips in a restaurant overlooking the harbour, watching the tide racing in across the sands. After lunch [our friends] sat on the beach while we explored – delightful little town, all higgildy-piggildy. …On the way out of the town we called at Bernard Leach’s studio… One of the greatest of modern potters.

At the studio we learned that Leach’s son David, who had for many years worked at and managed the St. Ives studio, now had his own pottery at Bovey Tracey in Devon, which happened to be on the back roads route the British Automobile Association had mapped out for us. As we descended from Dartmoor on our way home, there it was: Lowerdown Pottery. David Leach himself greeted us as, children firmly by the hand, we looked around. Although I had very little spare cash, I indulged and bought a pot.

Fast forward forty-nine years. At the urging of our family, Tony and I are trying to putting our affairs in order. We decide to start by making an inventory of our treasures. He photographs, I catalog. We come to the Lowerdown pot. Is it by David Leach or by one of his assistants or students? Its form has affinities with the work of Bernard’s friend Shoji Hamada, who is regarded as one of the most influential masters of studio pottery, and under whose tutelage David first learned the art.

Simon Leach, grandson of Bernard Leach, as shown on the book cover for Simon Leach’s Pottery Handbook—a book-and-DVD package.

By now David Leach has died, but I discover that his son Simon has also become an eminent potter. I find an email address on his website and write to him:

Dear Simon Leach,

About 1964 I visited Lowerdown Pottery and purchased a bowl from your father David Leach that has been a treasured possession ever since. I’m now trying to put my affairs in order for my heirs and am having a little difficulty finding a valuation for this piece — it seems most of his work is now in private collections or museums. It’s stoneware, 5.25 inches in diameter on a narrow foot with his impressed mark on the base. Here’s a picture. If you could give me an estimate of what it’s worth, or where I might turn for this information, I’d be most grateful.

Within a day I receive a gracious reply:

3/5/2013

Hi Maureen

Please send me an image of the seal on the base – clear and in focus also of the other side of the piece.

I will give you an approximate worth if I can.

Best Simon

With the requested images in hand, Simon again responded immediately:

3/6/2013

Hi Maureen

Having seen the seal I see that it is an L+ which means it was made at Lowerdown Pottery.

My father’s work had an Ld to the base. This means that it was not made by him personally…but by an apprentice or other potter there at the time.

Lowerdown pieces with an L+ are of course more plentiful than ones with the Ld so it’s value is somewhat less I would estimate.

I would say it’s value approximately would be in the range 80-100 pounds sterling.

If it had an Ld you might be looking at 250-300 pounds for such a piece.

That is the best I can do for you.

Best Simon

Not only did I have the documented valuation I needed for our inventory. I also had the pleasure of renewing a connection with this family of great British potters.

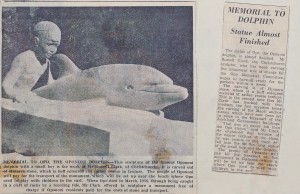

A taonga returns home

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

The manuscript is one my treasured possessions. I have pangs of regret about parting with it, but know I am doing the right thing. In New Zealand Tuwhare’s work is considered a taonga, a treasure. He was the first M?ori poet writing in English to win widespread acclaim. His best-known book, “No Ordinary Sun.” first published in 1964, was reprinted ten times over the next thirty years, becoming one of the most widely read individual collections of poetry in New Zealand history. The title poem is a response to French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Many more collections followed. His work has a conversational tone and incorporates both M?ori and biblical rhythms; the subjects range from the political to the personal and often powerfully evoke the beauties of nature. He won several New Zealand book awards, and was poet laureate of New Zealand in 1999–2000. He died in 2008, at the age of 85.

The M?ori concept of taonga also includes the story that goes along with the item. My little manuscript was a gift from Jean McCormack Tuwhare, Hone’s ex-wife. She and my mother-in-law were friends. On a visit to New Zealand in 2000, I spent a delightful afternoon with Jean at Mother’s house discussing poetry and literature. Mother had shown Jean my first poetry collection, “A Place Called Home,” and later suggested I send her a copy. Enclosed in Jean’s thank-you letter for the book was the Tuwhare manuscript. Unfortunately the letter is lost, but as I recall, Jean wrote that Hone (with whom she was still close friends) liked to practice calligraphy and had given her several of these small pieces to dispose of as she wished. She thought I might appreciate having one.

[Update 6/2/1016: While in New Zealand, I learned from Rob Tuwhare, Hone and Jean’s son, that Jean herself did the calligraphy, and Hone signed her work.]

I am of an age when I need to make decisions about my stuff. Knowing that the manuscript could easily get overlooked among our mountains of paper and art works, I sought professional help. I told Malcolm Moncrief-Spittle of Renaissance Books (New Zealand) , who deals in rare and out-of-print books, that I thought my taonga should be returned to New Zealand. Which university or cultural institution in New Zealand already houses a collection of Tuwhare material and would be a suitable recipient? I asked. He recommended the Hocken Library at the University of Otago in Dunedin.

Staff at the Hocken Library responded to my query with enthusiasm. We’ve arranged a meeting on May 9, when I will hand over the carefully packaged manuscript. I know it will be a happy/sad occasion.

An advocate for junk heaps

Cover and invoice of a 1964 informational booklet, “Creative Play” published by Paul & Marjorie Abbatt, Ltd. Image from Pinterest

By the time I interviewed him in 1963, Paul Abbatt and his wife Marjorie had spent thirty years as advocates for the importance of play in the development of young children and for the betterment of children’s toys and playing facilities. Toys commissioned by their toy company, Paul and Marjorie Abbatt Ltd. of 94 Wimpole Street in London, won prestigious international awards for their good quality and design. Paul Abbatt, whose chief interest was in ‘the ethos behind the business,’ delivered lectures and contributed to academic and professional journals on child development.

In 1963, Abbatt was focusing on outdoor playgrounds for older children. He commented that

“…as a society becomes more urban and industrialised, it becomes more and more hostile to the child and its needs. As buildings are packed closer and closer together, available sites become too valuable for industry, or for car parks, to be used for children’s playgrounds. Even the upper class child with a garden of his own is no better off, for custom demands that his parents keep their grounds neat and spotless, and the child has no opportunity for such fundamental activities as building a den, or digging down to Australia.

In keeping with the stereotypes of his time, by older children he meant older boys, assuming that a girl would be “already a mother with dolls, kitchen, a little house of her own.” The interview continues:

Mr Abbatt believes that the solution to the needs of the older child can be found in the adventure playground. The first of these was built several years ago in Copenhagen, where the designer, instead of putting in the usual concrete shapes, swings and slides, filled his playground with builders’ junk. The playground was a great success, and was copied all over Europe. Some cities produced old cars, or traction engines, used tires, and even an old boat.

The first experimental playgrounds, with their carefully manufactured playing facilities, had not been a success. The children were interested at first, but quickly gravitated to the streets just outside the playground, where they were closer to the real life that they knew. But when the material was provided on the sites for them to build their own dens, they could create their own world inside the playground. “Building a den seems to be fundamental to children’s play, and other activities develop round the original den,” said Mr Abbatt. In Zurich, for example, the gang who inhabited one playground built up such a community spirit that they had their own bank with its own play money, a duplicated magazine, an antique shop, and even a farm with a dozen ducks on a man-made pond. When each gang deserts the playground, as they eventually do, the dens are pulled down, and the next gang to come along starts from scratch with the pile of junk.

In the meantime, in Copenhagen, the first adventure playground has become something of a showplace for visiting social workers. The grounds have been tidied up, and the rough dens turned into pretty villas. The visitors look and admire, but the children no longer come.

Similar problems affect playgrounds in Britain. They are normally noisy, untidy, derelict places, a disgrace to the neighbourhood of neat houses with even neater gardens. So local residents complain, and the council tidies up the playground. “In doing so, they destroy the urge for creative activity that the previous junk-heap gave to the children,” said Mr Abbatt.

In preparation for a conference of the International Council for Children’s Play, which Abbatt helped found, he is making a descriptive survey of children in Britain.

He has invited parents to write and tell him what their children do, and, since small boys particularly are notoriously uncommunicative about the activities of their gangs, he is also seeking information from policemen, schoolteachers, traffic wardens, and others who see the children outside their homes. Already the response from parents has been overwhelming.

He hopes that the survey will provide town planners, architects, and designers, with information on what children really want out of their community.

In a note to my editor, I promised a follow-up when the survey results were in. I’ll talk about that in my next blog piece.

The last time I saw Paris

An old letter from my black file cabinet brought back memories of a brief vacation in Paris in 1962. Rereading the headlong, crammed-onto-the-page text, I hear again the breathless voice of a wide-eyed young traveler falling in love with the city of light.

I’ve not been back to Paris. It’s likely I never will. But, as in the old Jerome Kern song, I’m happy to remember her as I saw her back then.

Listen to Dame Kiri Te Kanawa

singing “The Last Time I Saw Paris.”

Windsor, 24 Sept

Dear Mum & Dad,

Breakfast tray at our door each morning: croissants with butter and jam, café au lait–the height of luxury.

Back home in England again, and not particularly pleased to be back to these bleak autumnal mists, and a real stinker of a cold to go with it—first cold I have had for ages. We had a wonderful week in Paris, and fell in love with the city. Left very early Monday morning—rose before the sun, about 5 am, and took off at 8 in a Caravelle, a very fast French jet plane, which landed us in Paris before 9 – though it was after 10 by the time we got to our hotel, which was in a little side street off one of the main boulevards. Rather noisy, at least for the first night, as it was close to the great city market, which does its business in the small hours of the morning. The second night we didn’t even notice it. Nice room, with a balcony from which we could watch all the goings-on in the street below—most entertaining. We spent practically every day walking—the number of miles must be pretty high. First morning we went down to the old centre of the city, the Île de la Cité, an island in the Seine, and had a look at Notre-Dame—I hope you got the postcard I sent you of it. Spent the rest of the day pottering round the island, along the banks of the river to the Tuileries, and back by a more or less circular route to the hotel. The next day we went up to the north side of the city, to the hills of Montmartre—fascinating streets, most of them ending in steps, somewhat like parts of Wellington, and with graceful balconied buildings with the plaster peeling off. About midday we went out to the woods of Boulogne, a huge park just out of the city, where we watched workmen playing at bowls in their lunch-hour. It is a sort of grown-up marbles, played with heavy steel balls that you throw to knock out the kitty. Then we went back to the Arc de Triomphe and walked down the Champs Elysees—lots of interesting shops, and the wide street incredibly tightly packed with vehicles—you look down the street and you see nothing but a sea of car roofs. Traffic in Paris is very thick, very, very fast (no speed limits) but amazingly well organized. Pedestrians beware though—they are very much second class citizens, and boy do they hop when the traffic starts to move. Anyway, back to Tuesday—later in the afternoon we went over and had a look at the Eiffel Tower—a remarkable piece of engineering. We didn’t go up it, however—we had already seen enough views of Paris from above, and weren’t very keen on its reputation for swaying.

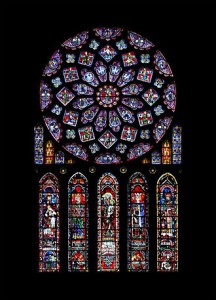

The next day we met my college friend John Wilson, who is at present living in Paris, and he took us out for the day in his little car, one of the new utility model Citroens. You may not have seen them in New Zealand. A chopped-off little bug, a bit ugly, very mass-produced, but able to go anywhere, very cheap, and very comfortable to ride in. There are thousands of them in Paris. Went first to Versailles, to look at the palace where the king and Marie Antoinette were taken from to have their heads chopped off. A most impressive building (though we didn’t have time to go inside), and the gardens are incredibly beautiful, in a cool, formal sort of way. Mostly vistas of fountains and pools, with statues, with a few formal flower beds, and woods beyond, laid out with a grace and elegance unknown to these more democratic times. We could have stayed there just wandering all day, but had to get going again, through side roads and quaint little villages. We had lunch in one, at a street café in the village square, just outside the gates of a very charming old chateau, whose towers were reflected in the canal close by. Then on to Chartres. The cathedral stands on a hill overlooking the plain, where there has been a church since the third century. This one was built in the 13th century, and was remarkable in that, except for part of one tower, which is noticeably odd, it was completed in thirty years. Outside very elaborate and impressive relief carvings in the porches, lots of gargoyles and what not.

You go inside, and it seems at first quite dark. Then gradually, as your eyes get used to the light, the huge pillars begin to appear, lit up by a pale greenish, strangely luminescent glow. Then you look up, and are practically dazzled in the burst of red and blue and green. The stained glass windows of Chartres are said to be the most magnificent in the world, and I can well believe it. To the north, south and west are huge rose windows, and all around are arches, each closely worked with many little pictures of saints, in incredibly fine detail. The result is a blaze of pattern and colour.

Then back the sixty miles to Paris, through wide open fields—no fences in this region, and the land is fairly bare of trees, and with a very gentle swell. It is a grain growing area—lots of harvesting machinery, and everything a beautiful golden colour—even the soil is the same colour as the wheat stubble. The next day we went to the Louvre museum, or at least to a small annexe, the Impressionists gallery—Van Gogh, Renoir and co., and discovered again the beauty of many of the paintings that we had thought a bit hackneyed in reproduction—things like Degas’s ballet pictures for instance—very beautiful and subtle in the originals. Spent all morning there, and in the afternoon walked over to the other side of the city, to see the UNESCO building, a very fine modern building. Our favourite part of it was a Japanese garden in the grounds, a little area of different levels and contrasting textures of stones and gravels, a stream and a pond, and a few bushes. Sounds rather stark and uninteresting to describe, but the result was charming, and very peaceful and relaxing. Friday back to the Louvre, to the main museum this time, but when you think that each of the wings of this is about a mile long, with several intersecting galleries about half a mile across, and all several stories high, you will realise that we didn’t see much of it, and even what we did see—mostly Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman antiquities, there were so many fascinating and beautiful things to look at that we didn’t do them justice—excuse for going back! Later in the afternoon we had to think of getting ourselves back to the airport. Bought some beautiful (smelly) French cheeses from one of the many street markets, then got out to the airport to catch our plane at seven. Wonderful to see the lights of London as we flew over the city—when we got under the cloud, that is. Very exhausted by the time we got home, but still wouldn’t mind doing it again. Though went into London yesterday, to see [our friend] Bill, an exhibition at the Tate, and a concert at the Festival Hall, and decided that London was rather lovely too.

Vive la France! Love, Maureen

Plumbing crisis brings neighbors together

Windsor Castle in the snow, January 1963. We lived in the town below the castle. Photo by Tony Eppstein.

The winter of 1962-63, my first in England, was the coldest Britain had known in over 200 years. First the fog crept in. My nostrils tightened against the thick yellow damp, sour with the smoke of coal fires and diesel trains. As November wore on and the cold deepened, fog froze into hoar frost that thickened daily on the power lines until they resembled sagging ropes.

Snow began the day after Christmas. All January it snowed and froze and snowed again. Transportation systems ground to a halt. The River Thames froze over. The inside wall of our apartment kitchen, wet since November and already black-mottled with mildew, glazed over with ice. On the outsides of buildings, ice congealed around plumbing outlet pipes like candle wax dripped from lighted candles. Water pipes froze and burst. The clatter of buckets as the water truck made its rounds became a familiar sound in our Windsor neighborhood.

Windsorians walk on the frozen Thames.

A view towards Windsor Bridge photographed on 24 January 1963. Image from the Royal Windsor Website

A side benefit of the bad weather was that we got to know our neighbors. Here’s a letter I wrote to my parents:

23 January 1963

I think we must be drifting into another ice age – the weather here continues to get colder every day. All sources of fuel – coal, gas electricity, and even paraffin, are in short supply, and everyone is fighting a losing battle against frozen pipes and general seizing up.

We had our fun and games over the weekend. We were woken fairly early on Saturday morning to terrific shouting and hammering on the door. We staggered out, to find that the Hoopers were being flooded out – their kitchen was an icy pond, and water was pouring through the light fitting in the ceiling. We turned off all the taps we could find, someone somehow found a plumber, and after he, Tony and Peter [Hooper] had hacked their way through the several inches of ice outside the front gate, and even more ice on top of the valve, they managed to get the mains off. Next thing we tried to get in touch with Stan Fricker, from whose flat the water was coming – he was at work, and we had visions of him coming home to a complete flood. By the time he arrived we had swished most of the water out of the kitchen, and had got all the heaters we could find in to dry it out. So we all trooped up into Stan’s bathroom, which is directly above the Hoopers’ kitchen and, to our surprise, found very little trace of water. We bailed the solid chucks of ice out of the bath, which had been frozen up for days, and Stan and Tony got to work on the floorboards, which were suspiciously damp. They managed to raise a couple, and discovered that the break in the pipe was right underneath the bath, which had been very recently closed in and modernised with plywood, fresh paint, and what not. A brute to get at.

The next thing to do was to find a plumber to fix it – easier said than done – “Oh no, love, we couldn’t possibly let you have one till Monday.” I don’t know how many pennies we spent on phone calls over the weekend, but at fourpence a call we went through several shillings. But we still couldn’t get a plumber till Monday, and late Monday afternoon at that. So we borrowed buckets of water from a neighbor, and puddled along with little dribs of washing where necessary, keeping most of it for drinking. It was pretty messy. At least in the old days they had facilities in keeping with such conditions – but try using a modern-type lav when you have nothing but half a bucket of dirty water to flush it with. That was the first thing that Margaret [Hooper] did, with great ceremony, when the plumber finally managed to get the water on again for us on Monday evening. Our lav had to wait a few hours longer – the remaining water in it had got so iced up that it had to be very carefully thawed before anything would move. And we still can’t have a bath – the outlet pipes in the bathroom are frozen up and, according to the plumber, that will just have to wait till the thaw.

The kitchen outlet, which comes down in the same place – down the outside wall on the coldest side of the house, now shows signs of doing the same thing, which would be choice. I am shortly going to do some washing, and hope that the gallons of hot water from the tub will deter it. Still, we could always throw our slops out the window – if we could unfreeze the windows enough to open them, that is. Might as well be really primitive.

We are getting rather advanced ideas on the proper requirements of a house in this climate – they do not agree very much with the conventional buildings most people live in here. Definitely central heating, double glazing, and interior plumbing.

Translucent angels

The glass artist John Hutton was on the list of New Zealanders living abroad that my editor at the Christchurch, NZ Press handed me when I left the paper in 1962. “He’s been working for years on a project for the new Coventry Cathedral. Go check out how it’s going,” he said.

Also known as St. Michaels, the original cathedral in Coventry, England was constructed between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. It was gutted by incendiary bombs during World War II; only the tower, spire, the outer wall and the bronze effigy and tomb of its first bishop survived. After the war, a decision was made to build a new cathedral and to preserve the ruins as a constant reminder of conflict, the need for reconciliation, and the enduring search for peace. The architect, Sir Basil Spence, proposed that the new cathedral should be built alongside the ruins, the two buildings together effectively forming one church.

Spence commissioned many magnificent art works for the new modernist building. Hutton’s contribution was to be a great glass screen for the west end of the new cathedral.

This image of Hutton’s great glass screen was posted by ashleyniblock on http://www.vortis.com/blog/

Unfortunately, the text of my interview is lost, but I still have a letter I wrote about our visit to Hutton’s studio near London:

May 9, 1962

One of the vases made by Hutton for sale at Coventry Cathedral. It is decorated with figures which appear among the images in the Great West Screen. It is now in the University of Warwick Art Collection.

Another artistic experience of a quite different sort was on Monday – we went out to interview John Hutton, a New Zealand artist who has made the great glass screen for Coventry Cathedral, which is to be consecrated this month. The panels are engraved with saints and angels, in a very bold scribbly style that nevertheless has a rich Gothic quality about it. We were very impressed, and also with his other work that he has at his studio – more glass work, but also paintings, and many other media as well. Just wish we had a hundred pounds to spare – he is making a series of vases, each engraved with two of the angels, which the cathedral is selling to raise funds.

Revisiting this story feels particularly relevant today. From the window of my office at the Christchurch Press, I used to look out at ChristChurch Cathedral, which was destroyed in the earthquake of 2011. Arguments are still going on about whether to rebuild or replace a building that was the physical and spiritual center of the city.

Discovering the familiar

When I first went to London, I already knew it, or thought I did. The literature I studied growing up was English literature – novels by writers who lived in England and wrote about English life. From them I learned to find my way around London in my imagination. When I finally walked the London streets in 1962, I recognized names every time I glanced at a signpost. From Dickens I’d learned about the Inns of Court and Chancery Lane. I knew that Savile Row was filled with bespoke tailors, though I had only a vague idea what “bespoke” meant. Bond Street was where expensive jewelry was purchased by upper crust people who visited expensive doctors on Wimpole Street. Carnaby Street was where fashionable young people bought the latest fashions. As a newspaper reporter, I revered Fleet Street, where the great London dailies were headquartered.

The BBC world news, which in New Zealand we listened to on the radio every day, opened with the chimes of Big Ben, the clock at the Palace of Westminster, where the British Parliament met. I knew the sound, but still could write in amazement to my parents: When Big Ben strikes the whole street reverberates.

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

Here’s a Wikipedia page that includes a recording of the St. Clement Danes bells.

I wrote in my notes:

[V]ery difficult not to associate names of places in London with famous songs about them – find myself starting to hum the songs as I read the names.

We went to Buckingham Palace, of course, and I thought of my childhood book-friend Christopher Robin:

They’re changing guard at Buckingham Palace –

Christopher Robin went down with Alice.

Alice is marrying one of the guard.

“A soldier’s life is terrible hard,”

Says Alice.

My memory of those first few days in London is a sense of wonder and excitement as places became real. At the same time, there was a disconnect. I had to let go of expectations that special buildings, Sir Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s, for instance, were set off from other buildings, up on a pedestal, giving off a radiant glow. Reality was grimy walls and a crushed cigarette packet in the gutter. I wrote:

Peculiar sensation frequently of almost having been here before – not the usual one, connected with place, but connected with names – so familiar, and the outlines themselves so familiar, except that until now we had not known how they stood in the context of the rest of the city. –so this is Big Ben – so this is St. Paul’s – and we know they are, we have always known them, but we did not know that we would find them just here, with this office building on this side, and that park or square on the other. To walk down to the Embankment, and just happen to come upon Cleopatra’s Needle, standing so casually by the river. Somehow I had expected the great tourist attractions to be set apart, and gazed at always in awe. It is a jolt to realise that millions of people live and work alongside them every day of their lives, and take them so much for granted that they hardly see them. They leave the gawking to the tourists, who pour in by the busload, scatter their trash, and depart. The permanent thing is the life that goes on all around these not so very sacred objects, and of which they form a part.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Art stuns like a hammer blow

With gold velvet drapery as backdrop, the newly acquired Rembrandt, “Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer,” stood on an easel in the foyer of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Spotlights accentuated the golden glow of the painting’s surface. As I gazed, I felt a resonance with the feelings of the person depicted, my thoughts drawn into his as if into a dizzying vortex. I was astounded that brushstrokes and pigment could have such power to move me.

I had not seen great art before, except in books of reproductions. I had devoured the collection of large format books in my high school art room, and spent hours browsing the art section of secondhand book shops when I was in college. When we left New Zealand in 1962, Tony and I had as a priority to visit art museums and see the work of artists we admired. But nothing had prepared us for being in the presence of the real thing. Upstairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art we found a whole room of Rembrandts. Dancing down a broad staircase, a whole series of bronze sculptures by Edgar Degas. We saw so many great works we discovered the phenomenon we named “mental indigestion” and wished we had more time in the city so that we could come back. We knew it would take weeks, months even, to absorb all this museum had to offer.

We visited other art museums during this stopover in New York on our way to England. Some we loved, some less so. In a letter to parents I wrote: “Sunday afternoon we went out to The Cloisters, which is right up at the northern tip of Manhattan. This is a religious museum. Parts of the remains of many old churches of Europe have been brought across and incorporated into the present structure, which keeps as closely as possible to the original styles. In a sense it is a success – some of the old fragments of stonework are very fine, and there are some very fine paintings, altar ornaments, and some magnificent tapestries – the highlight of the whole exhibition. But in spite of their attempts to reproduce chapels, all sense of reverence has been lost – the things are a curiousity for the locals to gawp at, and even sacrilegious.”

As I look back on these youthful letters and these memories, I see opinions about what matters to me already forming and clarifying. Many more experiences of the power of art would come in future years: sitting on a bench in a crowded London gallery, weeping over Georges Rouault’s “The Old King;” gazing in awe at the rose window in Chartres Cathedral; feeling the silence of the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Always, enriching these experiences, the memory of that stunning awakening in New York.

The End of a Great White Ship

The memoirist Judith Barrington and I have a ship in common. Her memoir Lifesaving has at its center the cruise ship “Lakonia,” which departed Southampton on December 19, 1963, on a Christmas voyage to the Canary Islands. Three days later, a fire broke out. In the ensuing confusion and panic, a small group of passengers, including Judith’s parents, were left stranded without lifeboats and drowned.  Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

On February 13, 1962, the previous year, my husband Tony and I left New Zealand on that same ship. At the time her name was the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt,” of Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN), also known as the Netherland Line. It was not quite her last round-the-world voyage under this flag; the maritime historian Reuben Goossens notes that her final departure from Wellington, NZ was in January 1963.

“What was it like on board?” Judith asked me. “I know my parents were on a cruise ship, but I can’t get a picture in my head of those staterooms or of being on that deck.”

I told her as best I could of the richly carved dark wood paneling that decorated the staircases and staterooms. Reuben Goossens notes that the décor was the work of famed Dutch artist Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945) and sculptor Lambertus Zijl (1866-1947). Lion Cachet “took a great delight in using some of the most exotic timbers and then mixing them with a range of materials, from marble, polished shell to tin and other unique materials. Décor throughout the ship reflected the colonial links between the Netherlands with the Far East.” Lambertus Zijl created many fine sculptures and reliefs that were to be found throughout the ship.

Cover of a JVO dinner menu. We collected and framed several of these, each showing a different bird.

Tony and I also had the sense of being on a ship with a long history. The JVO, as we lovingly called her, was launched in 1929, and was one of the most luxurious ships to be placed on the international trade route to the Dutch East Indies. She was requisitioned as a troop ship during world War II. After the war, she brought large numbers of British and Dutch immigrants to New Zealand under a government-sponsored program that provided free or assisted passages.

Refitted as a one-class cruise ship in the late 1950s, the JVO offered round-the-world and trans-Tasman cruises. Competition from airlines was by then reducing the demand for ships as a standard mode of passenger transport across seas, though airfares were still way beyond the means of most young New Zealanders. We obtained a lower level berth on the JVO for about $160 each. According to a 1963 Pan Am schedule an airline ticket from Auckland to London would have cost about $900.

So the JVO was sold in March 1963 to the Greek Line, and renamed the “Lakonia.” The cruise on which Judith Barrington’s parents perished was her maiden voyage under her new flag.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Dolphins of Yesteryear

A 55-year-old news clipping brings back memories

An old black metal filing cabinet sits in my cluttered attic. Stuffed into its four drawers are fifty-five years of my stories, some published, most not. Sooner or later someone will have to dispose of all the dog-eared pages and travel-worn manuscript boxes. In the meantime, I’ve set myself a little project for this blog: go through the files and find pieces of my past that you, my readers, might find interesting.

Here’s one, to start us off. On January 6, 1960, I was fresh out of college, and this was my first day on the job as a cub reporter at The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. My boss, the city editor, handed me a four-year-old clipping about the death of Opo, a bottlenose dolphin who chose to join children at play in the surf at Opononi, a beach settlement in the Northland region. The grieving residents had commissioned a statue. “Here, update this story,” he said. “The sculptor lives in Christchurch. His phone number’s in the book. I’ve heard he’s nearly finished.”

I had a pleasant conversation with Russell Clark, the sculptor, who was making the sculpture free of charge as his tribute to Opo. It is of Hinuera stone, which is buff colored and coarse in texture. The sculpture was indeed nearly finished, and would be shipped to Opononi the following week. I was so proud when my little story appeared exactly as written, along with a nice photograph, in the next morning’s edition, having survived unscathed the eagle eyes of The Press’s copy editors, gruff eminences who ruled from a curved dais in back of the press room.

I did not meet Opo, but have my own dolphin memory. We were returning from a family vacation on Tuhua, an island offshore from Tauranga. The day was brilliantly sunny, the launch was bouncing through waves, and I had just learned that I’d been awarded a national scholarship to attend university. A school of dolphins surrounded the boat. Leaping joyously through the waves, they escorted us back to land. As I stood at the bow, I felt like a princess.