Archive for the ‘trees’ Category

Death of a Christmas Tree

We’d bought the young spruce in a fit of environmental consciousness when we still lived in Cupertino, CA. and it served as our Christmas tree for several years. In 1973 it survived our move to Santa Barbara, carefully bolstered in the U-Haul truck so it wouldn’t get smushed. It put up with a year or so of Santa Barbara sunshine, had even come into the house one holiday season. But that year, 1975, the temperature spiked into the 80s just after Christmas and hot sun streamed into the house. I was too busy with holiday guests and activities to think about moving the tree outside into the shade, so it stayed inside far too long. By the time we disburdened it of its decorations and lugged it back outside, the damage was already done. Months later, when I could no longer bear to look at pathetic brown needles, I removed it from its pot. The roots were tightly bound around each other.

One received wisdom is that you buy a potted tree for the holidays, then plant it in your garden. But this is not realistic if the tree’s grown size will overpower existing plantings, or if its natural habitat is elsewhere. I found a curious example of this when a few decades later we moved to Mendocino. In the patch of native forest on our property I found two trees with silvery needles. A naturalist friend identified them as some kind of spruce, definitely not native. She told me the story of how they most likely got there. The original developer had been hauled into court for illegally logging the property to create a “view development” and was ordered to replant. She speculated that he picked up a job lot of leftover Christmas trees to fulfill this requirement. Our two spruces, crowded out by redwood and Douglas fir, did not survive much longer.

So what to do about a Christmas tree? Over the years we’ve tried various approaches. We’ve gone to cut-your-own tree farms. But sawing into a young tree felt like committing murder. We’ve bought a cut tree from a lot and kept it outside in a tub of water for as long as possible. Even so, it would be shedding needles even before it came into the house. It would have been been cut weeks before, and shipped hundreds of miles from where it was grown. We’ve thinned out young firs from our own property. But they’ve been spindly little things, too likely to topple.

For the past couple of years, we’ve not bothered with a tree at all. I’ll maybe clip some low-hanging conifer branches to make a big arrangement in a bowl on the dresser or a wreath for the door. But that’s about it. I like my trees living. Like this baby Grand Fir that workers clearing a drainage channel a few weeks ago rescued from an overgrown coyote bush and saved for me.

They paved paradise

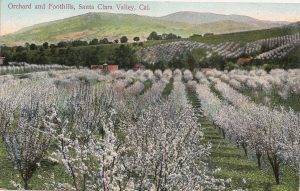

Golden fruit clings to leafy branches. Golden-skinned men climb orchard ladders, old metal harvesting pails in hand. Close to the road, a huge billboard: FOR SALE FOR COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT. The scene has stayed in my mind, my first introduction to the landscape of my new home.

I moved, with husband and children, to Cupertino, in Santa Clara County, California, in late May of 1967, just as the apricot harvest was beginning. Between our apartment, off N. Blaney Ave. by Interstate 280, and the nearest food market, on Stevens Creek Blvd., was a mile of apricot orchards. In other directions were acres of cherries, almonds and prunes. The Santa Clara Valley, a fertile alluvial plain, was until the 1960s the largest fruit production and packing region in the world. The beauty of all that spring blossom gave rise to the nickname “Valley of Heart’s Delight.”

The post-World War II economic boom and the rise of high-tech industry changed all that. My husband and I were part of a flood of new arrivals that forced out the fruit farmers and replaced orchards with tract houses, shopping centers, and business parks. It was a bittersweet time. On the one hand the energy and excitement of the new technological advances, the sense of living where the future started. On the other, sadness at the destruction of all those beautiful trees. Among my old notes I found a few lines of a poem I wrote in those early years:

The field is bare now where the orchard stood.

Apartment builders hammer at its brink.

How soon do we evict the meadowlarks

that saunter golden in the rainy dusk,

foraging through weeds by the highway’s edge?

In recent decades, with the growth of the environmental movement, there grew a collective sense that something important was being lost. Efforts were made to preserve at least the memory of that fruitful landscape. In 1994, the City of Sunnyvale preserved ten acres of Blenheim apricot trees “to celebrate the important contribution of orchards to the early development of the local economy” and created an interpretive museum beside it.

The Olson family, whose 100-acre cherry orchard was one of the last vestiges of cherry farming in the area, still retains a few acres of trees and the roadside fruit stand that began in 1899. Owner Deborah Olson commented: “We try to educate people just moving in to the area, who don’t know what it’s all about. They get a sense of place, about how it began here, and they kind of feel a part of the community.”

Blogger Lisa Prince Newman, whose family also moved to the valley in the 1960s, is collecting stories, pictures and apricot recipes from the few farming families still in the valley.

The chorus of Joni Mitchell’s song “Big Yellow Taxi,” written in the late 1960s, sums up the sense of profound loss:

Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

Till it’s gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

Hear Joni sing “Big Yellow Taxi”

A Shakespearean ghost and an old tree

Herne’s Oak, Windsor Park circa 1799

Etching with hand colouring, attributed to Samuel Ireland (1744-1800). The two Merry Wives of Windsor, Mistress Page and Mistress Ford, are standing with Falstaff at Herne’s Oak.

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

In the grounds of Windsor Castle in England stand thousand-year-old oaks so huge and gnarled and blasted it’s easy to imagine them haunted by spirits. Shakespeare used this conceit in his play “The Merry Wives of Windsor.”

When I was a Windsor wife in the early 1960s , I attended a performance by the Windsor Repertory Theatre of “Merry Wives” one summer evening in the castle gardens. Probably written to amuse Queen Elizabeth I, the play uses as its setting then-familiar Windsor landmarks, such as the 14th century Garter Inn on High Street and Herne’s Oak in Windsor Great Park.

The play centers around the drinker and gambler Sir John Falstaff, known from the plays Henry IV part 1 and part 2. Short of money, he comes to Windsor where he attempts to seduce both Mistress Page and Mistress Ford in hope that at least one of them will share her husband’s wealth with him. He writes each wife an identical letter, but the two women, who are close friends, immediately show each other their letters and are outraged.

The wives decide to teach Falstaff a lesson, and pretend to lead him on while planning his downfall. He is dumped from a laundry basket into the muddy River Thames, and beaten while disguised as the Old Woman of Brentford, who is believed to be a witch. With their husbands in on the secret, they concoct a final revenge for his clumsy insults to their virtue. Mistress Page sets the scene:

There is an old tale goes that Herne the hunter,

Sometime a keeper here in Windsor Forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree, and takes the cattle,

And makes milch-kine yield blood, and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner.

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Receiv’d, and did deliver to our age,

This tale of Herne the hunter for a truth.

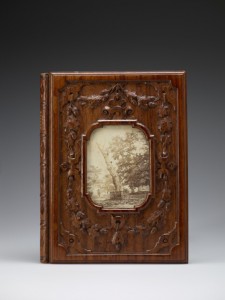

Cover of William Perry’s “A Treatise on the Identity of Herne’s Oak, Shewing the Maiden Tree to Have Been the Real One”

Probably presented to Queen Victoria by William Perry, c. 1867

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

The Royal Collection website notes:

Perry’s treatise claiming the authenticity of this tree echoed Queen Victoria’s own belief, though his view was not entirely unbiased since he had been given portions of the wood to carve into souvenirs, which include the binding of this book. A photograph of the tree shortly before its fall is inserted in the front board.

Falstaff is induced to dress as the ghost of Herne the Hunter and wait for the two women at Herne’s Oak, where he is pinched and tormented by local children dressed up as fairies.

Since Herne’s Oak has now fallen, exactly which tree it was—the one that fell in 1799 or the one in 1863—remains in dispute. Also unclear and undocumented are the origins of the myths about Herne the Hunter. Shakespeare was the first writer to mention him. His purported connection to ancient archetypes representing the primal power of nature may be an artifact of Victorian story-makers. Some evidence suggests there was a real game-keeper in Windsor Great Park named Herne or Horne, possibly in Elizabeth I’s time, possibly earlier, who, having committed some great offence for which he feared a dreadful punishment, hanged himself on an oak tree. Maybe Mistress Page had it right: the memory of such an event at a scary-looking tree could be enough to start a legend about a ghost.

A cool way to help restore a forest

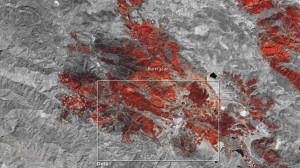

In neighboring Lake County this past summer, wildfire destroyed 76,000 acres of forest (about seven million trees) and nearly 2000 homes, businesses and other structures. Mendocino Coast Botanical Gardens has stepped up with their Lake County Giving Project. One component of the project encouraged people to purchase potted trees and other plants for their holiday decorations, then bring them back to be donated to Lake County residents rebuilding their homes.

Zoomed-in false-color shortwave infrared satellite image showing the Valley Fire burn scar near Middletown, California on September 20, 2015. Burned areas appear orange or dark red. (NASA Earth Observatory)

The other component of the Giving Project is seed balls. With advice on plant species from the USDA Resource Restoration Project and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Wild Jules is crafting seed balls of wild grasses, perennials, and annual wildflowers for habitat restoration in the fire-ravaged areas. According to the Wild Jules website, “Individual varieties of seed are proportionately mixed with red clay and compost to provide a self contained method of spreading native varieties. The ball protects the seed from birds and rodents. The seed cannot dry out or blow away. The best part is, you can cast these ‘jules’ (jewels) out on top of the soil any time of year. The seed within the clay balls will wait patiently to germinate until adequate water is applied by way of rain or irrigation.”

A Wild Jules seed ball. The balls being prepared for Lake County habitat restoration are a little more flattened so that they stay put on steep hillsides.

Tony and I were intrigued enough to stop by the Garden Store to donate a few dollars to the seed ball purchase fund.

Julie Kelly, founder of Wild Jules, says: “It’ll take many years but every bit counts. The perennials won’t bloom this year, but the annuals will. They will help feed foraging insects and birds and lift the spirits of the folks so terribly impacted.”

The Language of Plants

Have you ever wondered whether trees talk to each other about what’s going on in the forest? Can they show compassion or motherly love? Do they team up to ward off an attack?

Recent research has shown that plants communicate using an electrochemical “language.” Taking a break from exploring my old black filing cabinet, I’d like to share a poem about this discovery. It’s from my new collection, Earthward, available from Finishing Line Press.

The Language of Plants

We who move about are at a loss.

We do not know what words to use

for speech that has no metaphor

in the human tongue.

We have ways to speak of learning,

words for memory, decision-making words.

We speak of synapses of neurons in our brains,

name the organs that receive our senses—

ears, eyes and noses, taste buds, fingertips—

words all based on human forms.

The standing-still ones

message their pheromones into the air:

Aphid invasion. Deploy toxin defenses.

Send for the predator wasp to counter-attack.

Roots zing with electrochemical charge

as through their internet—

a mycorrhizal tangle of yellow threads—

they share resources with their kin,

and even with neighbors of other ilk:

Fir borrows summer sugar from birch,

pays it back in the time of barren twigs.

We need new definitions to embrace

the beings who feed on light

not in some alien galaxy

but close at hand:

Does intelligence mean to have a brain

or problem-solve?

New ways of standing in a bean patch

or a forest grove

in awe and wild surmise at all

this human brain can not yet comprehend.

The Standing Still Beings

With enough imagination, any group of two or three lines or dots can become a face. Sunlight filtering through the forest one afternoon this week made me see faces in an old redwood stump I passed as I strolled down the service road to our neighborhood’s pump house in Jack Peters Creek. The “eyes” and “mouth” are actually slots hacked by long ago lumberjacks to cantilever the boards on which they would have stood to saw down the giant tree.

I was drawn to these “faces” because of a recent New Yorker article, “The Intelligent Plant” by Michael Pollan. In it, Pollan notes how wary many scientists are of any hint of parallels between animal senses and plant senses, or of suggestions that plants have intelligence, which he defines as “capable of cognition, communication, information processing, computation, learning, and memory.” Pollan goes on to describe a number of plant studies that do indeed demonstrate such capabilities.

The problem is language. The words we have for intelligence in the animal world (brain, neural networks, etc.) and for the tools of sensory information (ears, eyes, nose, etc.) don’t work for beings whose mode of communication is complex biochemicals: pheromones transmitted by leaves through the air, and electrochemical signals sent by root tips through a network of mycorrhizal fungi. It’s as if we were trying to comprehend and describe the lives of beings on an alien planet.

What I took away from Pollan’s article was a renewed respect for the beauty and complexity of our natural world, and a renewed awareness of how much we humans don’t yet understand. I know the “faces” are just human-made gashes in the trees. But they serve to remind me that I, who have legs to move around, live among the standing still beings, of whose lives I am ignorant.