Archive for the ‘seasons’ Category

Death of a Christmas Tree

We’d bought the young spruce in a fit of environmental consciousness when we still lived in Cupertino, CA. and it served as our Christmas tree for several years. In 1973 it survived our move to Santa Barbara, carefully bolstered in the U-Haul truck so it wouldn’t get smushed. It put up with a year or so of Santa Barbara sunshine, had even come into the house one holiday season. But that year, 1975, the temperature spiked into the 80s just after Christmas and hot sun streamed into the house. I was too busy with holiday guests and activities to think about moving the tree outside into the shade, so it stayed inside far too long. By the time we disburdened it of its decorations and lugged it back outside, the damage was already done. Months later, when I could no longer bear to look at pathetic brown needles, I removed it from its pot. The roots were tightly bound around each other.

One received wisdom is that you buy a potted tree for the holidays, then plant it in your garden. But this is not realistic if the tree’s grown size will overpower existing plantings, or if its natural habitat is elsewhere. I found a curious example of this when a few decades later we moved to Mendocino. In the patch of native forest on our property I found two trees with silvery needles. A naturalist friend identified them as some kind of spruce, definitely not native. She told me the story of how they most likely got there. The original developer had been hauled into court for illegally logging the property to create a “view development” and was ordered to replant. She speculated that he picked up a job lot of leftover Christmas trees to fulfill this requirement. Our two spruces, crowded out by redwood and Douglas fir, did not survive much longer.

So what to do about a Christmas tree? Over the years we’ve tried various approaches. We’ve gone to cut-your-own tree farms. But sawing into a young tree felt like committing murder. We’ve bought a cut tree from a lot and kept it outside in a tub of water for as long as possible. Even so, it would be shedding needles even before it came into the house. It would have been been cut weeks before, and shipped hundreds of miles from where it was grown. We’ve thinned out young firs from our own property. But they’ve been spindly little things, too likely to topple.

For the past couple of years, we’ve not bothered with a tree at all. I’ll maybe clip some low-hanging conifer branches to make a big arrangement in a bowl on the dresser or a wreath for the door. But that’s about it. I like my trees living. Like this baby Grand Fir that workers clearing a drainage channel a few weeks ago rescued from an overgrown coyote bush and saved for me.

The Easter Bunny mystery

How could my husband and I be so mean as to deny our kids the Easter Bunny? I frowned as I reread the letter to my parents stashed in my old black filing cabinet.

12 April 1971

The kids are back at school today after their week of Easter vacation. The weather has been so beautiful and spring-like. This is something I couldn’t really understand until I came to the northern hemisphere—the significance of Easter as a spring festival—the death and rebirth of the god that is an important part of almost every religion there has ever been. Here a big thing at Easter is the Easter Bunny, who is alleged to bring baskets of candy eggs and goodies to kids on Sunday morning. This Tony and I just can’t go along with—somewhat to the kids’ disappointment, I think, though we do buy them a fancy Easter egg, and of course we have the fun and mess of dyeing hard-boiled eggs and hiding them in the garden for an egg hunt. I did allow Simon to share our pet rabbit at school one morning. Bun-Bun was less than enthusiastic about the whole project, but the children were ecstatic.

Part of the reason for our rejection of the Easter Bunny was that Tony and I grew up in New Zealand, where rabbits were despised as pests. Brought by early settlers to a place with no natural predators, their population quickly reached plague proportions, causing major erosion problems. We did have Easter eggs, but given that we celebrated the festival in the Southern Hemisphere autumn, they had no significance other than as a source of sugar and chocolate. Even living in California, we couldn’t see any connection between rabbits and the Christian celebration of the Resurrection. I decided this week to look into the question. I quickly found myself down a fascinating rabbit hole of customs, beliefs, and theories, many of them contradictory.

How the Easter Bunny came to the U.S. seems pretty clear. According to several sources, the creature first arrived in America in the 1700s with German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania and transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws” who brought colored eggs to good children at Easter. As the custom spread across the U.S. the hare somehow transformed itself into the more familiar rabbit and its Easter morning deliveries expanded to include chocolate and other types of candy and gifts.

The hare’s (or rabbit’s) connection with Christianity are more complicated. For the first few centuries, the Christian festival coincided with the Jewish Passover, which is when the historical events surrounding Jesus’s death occurred. Though the Christian calendar has since been modified, both festivals are still close to each other in spring. Both are based on a lunar calendar; the date of Easter was defined in 325 CE by the Council of Nicaea as the first Sunday after the first Full Moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox. In Anglo-Saxon regions of Northern Europe, the Christian festival seems to have merged with a pre-existing equinox festival honoring Eostre, the goddess of spring, and Christians continued to use the name of the goddess to designate the season. Since hares and rabbits give birth to large litters in early spring, they have long been recognized as symbols of the rising fertility of the earth at the vernal equinox.

No, no, no, say some Catholic writers. The Easter Bunny has Christian origins. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that the hare could conceive again while pregnant, thus shortening the time between litters and delivering more offspring during a breeding season. Later Greek writers such as Pliny and Plutarch expounded the notion that hares (and rabbits, by association) were hermaphrodite, and thus could self-impregnate and reproduce as virgins. During the medieval period, hares and rabbits began appearing in illuminated manuscripts and paintings depicting the Virgin Mary, serving as an allegorical illustration of her virginity.

Two pregnancies at once? Intrigued, I veer into another passageway of my research rabbit warren. It turns out that, as the Smithsonian Magazine put it, “Aristotle got it right: the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) can get pregnant while it’s pregnant.” In 2010, scientists of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, Germany, led by Dr. Kathleen Roellig, published the results of their study. Using selective breeding and high-resolution ultrasonography, they showed that a male hare can fertilize a female during late pregnancy. The resulting embryos will develop around four days before delivery of the first pregnancy. To quote from the Smithsonian article: “The embryos don’t have any place to go at that time, however, since the uterus is occupied by the embryos’ older brothers and sisters. So the embryos hang out in the oviduct, rather like when you wait in your car for a parking space to open up. Once the uterus is free, the embryos move in.”

My head is spinning. I think I need chocolate.

The way we learn to belong

Once more we are at that seasonal turn familiar in California history: after a winter of great rains, floods and mudslides, the promise of an extraordinary blaze of color as wildflowers burst into bloom. My first experience of this magical transition was in 1969, my second spring in this new country. I describe it in letters to parents:

Feb. 28, 1969

It has actually stopped raining for the past hour. Another shower on the way, of course, but such a respite to see the sun. We have been averaging one sunny day a week for the past two months, and the general situation is already critical. We are not doing too badly in the Santa Clara Valley. All the creeks are contained by reservoirs up in the hills, and although the largest one, Anderson, is spilling over the top and flooding parts of east-side San José, the others are still holding their own. Fortunately the weather-man had predicted a respite for the next four or five days, i.e., drizzle instead of a deluge, and the authorities are hoping to get enough water away through the sluices of the other six dams during this time to make room for next week’s storms. Where we live is on relatively high ground anyway, so it is unlikely that we would be affected. The really big headache though is Central Valley, which drains the whole of the Sierra Nevada range. The Sacramento-San Joachim delta has flooded twice already in the past two months, and the river levels are still dangerously high. But in the high Sierra the snow fall is already twice the annual average, and we are only one third through the rainy season. Sooner or later that stuff is going to thaw, and if there is a warm rain up there, the effect will be sudden and disastrous. Meanwhile, it is still raining, with violent storms rolling in from the Pacific with tedious regularity. For some vast meteorological reason, the storm belt has swung further south than normal this year—so we are getting what Alaska usually gets. (They say it’s a mild winter in Alaska this year!)

A field of mixed wildflowers: Arroyo Lupine, Baby Blue-eyes, Purple Owls Clover and Tidy-tips. Image from Mother Nature’s Backyard.

And a few weeks later:

April 14, 1969

[After a visit to the Lick Observatory on Mt. Hamilton] We decided to see what it was like on the other side of the mountain. We found ourselves in a charming little valley, the San Antonio, which we followed back to Livermore and the freeway home. The land in this part is lightly wooded, and very sparsely populated—we saw a few ranch houses, occasional small herds of cattle, the odd horseman and dog, and that’s all. And at this time of year, the earth between the trees is covered with fresh grass, so scattered and strewn with wildflowers that it looks like some magic carpet.

I think it is one of the most wonderful sights I have ever seen. Great swathes of colour, of every shade. One they call Sunshine, or Goldfields, a tiny daisy-like flower, brilliant yellow. It grows only a few inches high, but in such profusion that, as its name implies, it makes a great field of colour. And on the slopes of Mt. Hamilton we thought for a while the snow was still lying, there were such patches of a snowy white flower. But other colours too, pinks and blues right through to the purples and reds. And down in the lower valleys, the California poppy, a brilliant orange. …I love these flowers so much.

An interviewer recently asked me what moved me toward writing about nature. I replied that as an immigrant, learning about the land was a big part of learning to belong to my adopted country. I’ve found this be particularly true when I moved from the Bay Area to the Mendocino coast. I’ll always be grateful to Dr. Teresa Sholars, whose College of the Redwoods wildflower identification class gave me the names of beloved beauties. Here’s a poem about them:

California Wildflowers

It seems a simple joy

to greet the flowers by name

Tidy Tips, Goldfields, Blue-Eyed Grass,

Crane’s Bill and Cream Cup,

Sticky Monkey Flower,

Mule’s Ears, Owl’s Clover,

Sun Cups glossy by the path,

Milkmaids in shade,

Lupine and Poppy on the slope,

but to the immigrant who after 40 years

still speaks with foreign intonation,

these are pet-names for familiars

precious as friends,

who speak in a language without words

of soils: clay and serpentine,

of rains and drought,

the way the lineaments of the land

impress themselves,

the way we learn to belong.

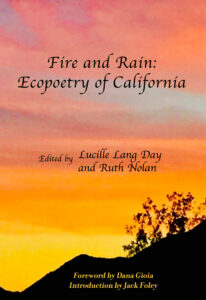

In a couple of days I’m off to Portland, OR for the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) conference. I was invited to be part of a group representing Scarlet Tanager Books, publisher of the anthology Fire & Rain: Ecopoetry of California, in which I have several poems. We’re hosting a reception at the conference, and doing a reading at a neighboring bookstore. Being recognized as an “ecopoet of California” makes me feel that, after what is now 52 years, this beautiful state is home. Enjoy this season’s flowers.

The nesting instinct

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

Feb. 2, 1970

… I cleaned the apartment, then of course rushed back here to try to get a bit more cleaning up and unpacking done. The previous owner was a pretty sloppy housekeeper – still, I guess everyone complains about the other woman’s methods. Anyway, most of the house is now more or less presentable …

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Or, as webmd.com puts it: “Just as birds are hardwired to build nests for protecting their young, we humans are primed to create a safe environment for our new offspring.”

I wasn’t pregnant in 1970, so I looked up sites with information on spring cleaning. I found checklists, some tentative discussion of the custom’s origin in ancient traditions and religious practices, as well as practical reasons for the task, especially in places of cold winters and times of sooty wood- and coal-burning heating facilities. And on sites about moving into a house, there were checklist after checklist, all of them assuming that the previous owner/tenant is by definition a germ-carrying slob, and that the new occupant is motivated to clean every inch of the place. A few examples:

From Angie’s List:

- “Previous residents surely cleaned the bathroom, but there is no harm in scrubbing away your own way as this room can be one of the more germ-filled places in the house.”

- “The insides of all cabinets and drawers were most likely ignored by the previous tenants or homeowners.”

- “Dust the top of the doors and disinfect all doorknobs.”

From Bed Bath & Beyond:

- “Your dream home sure looked spotless during the open house. But gird yourself: No matter how clean the place seemed, it’s likely there are some dirty surprises in store for move-in day.”

[This site pays particular attention to chandelier light fixtures, crown moldings, ceiling fans, doors & knobs, refrigerator vent, dishwasher, furnace, ductwork, washer & dryer]

From The Spruce:

- “You should always do a thorough clean before your stuff arrives.”

- “The kitchen is probably the first place to start. Not only because it tends to be where icky sticky things collect, but also because you’ll want to get rid of the former tenant’s cooking smells.”

[Detailed instructions for fridge, stove, cabinets, counters, sink, walls, floors]

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

The turning of the year

Here we are at the turning of the year. It’s been a hard year in many ways. My particular concern has been the environment and natural resources. I’ve had to witness oil and gas interests take precedence over the protection of fragile landscapes, sacred cultural resources and vulnerable water supplies. Wildfires have devastated Northern California, where I live, including parts of Santa Rosa, the city where we go for many services. A huge fire now threatens Santa Barbara, in southern California, where I lived in the 1970s. Here on the northern coast, warming ocean temperatures have wrought havoc on the kelp forests and the sea creatures that depend on them. Throughout the world, as starving people flee drought-stricken lands, tribal hostilities are increasing.

Meanwhile, the days follow each other. The sun’s arc rises lower and lower in the sky, its rising and setting further and further to the south, and the darkness of longer duration. There will be a pause, a solstice or sun-standing-still, and then a return of the light, and we will celebrate, in our various spiritual traditions, a return of hope.

May you all find hope and joy in the days to come.

The rain in Camelot

When I arrived in California from England’s green and rainy land, I thought I must have landed in Camelot. Remember that song from the 1960 Lerner & Loewe musical?

The rain may never fall till after sundown

By eight, the morning fog must disappear

In short, there’s simply not a more congenial spot

For happy-ever-after-ing than here in Camelot

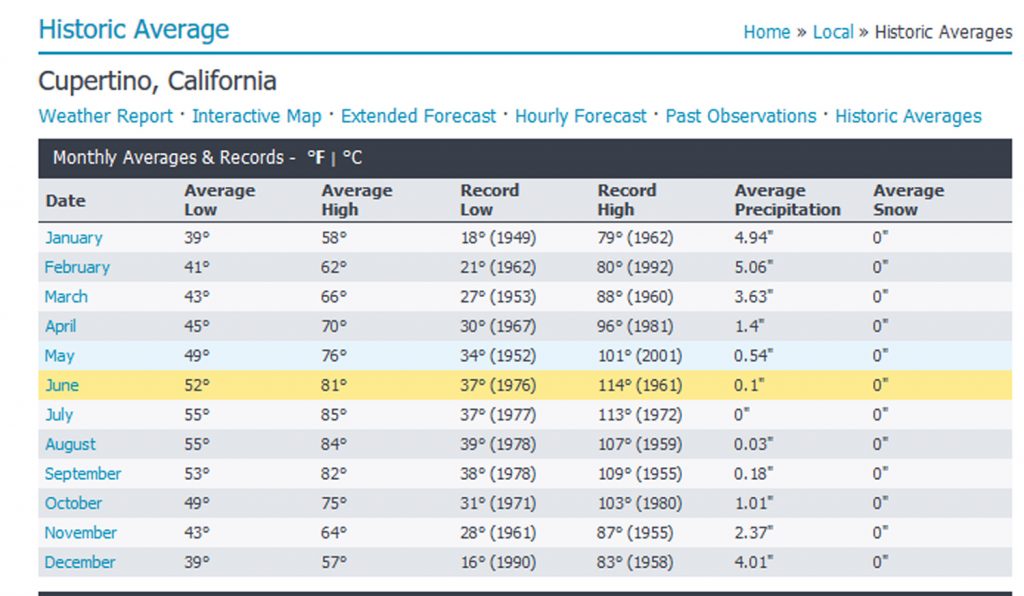

It rained for a week or two after we arrived, from late May into early June. My new neighbors kvetched, “Enough already!” After a normal rainy winter, early spring had been dry. Now the rains had started back up, and they didn’t like it. I, however, was enchanted. It truly only rained at night; the days were warm and sunny.

Eventually the rain stopped. Grass on the hills turned from green to gold. I had learned about Mediterranean climate in geography class at school: how it occurs only in five parts of the world, on the western sides of continents, between roughly 30 and 45 degrees north and south of the Equator. How it is associated with rotating high pressure zones that migrate through these sub-equatorial latitudes depending on the angle of the sun, bringing clear skies in summer and moving equator-ward to allow frontal cyclones to bring rain in winter.

A classic California landscape: Mt. Hamilton, to the east of Cupertino. Image from http://www.pleinairmuse.com/

Now I was living this rare climate. Warm sunshine day after day. Golden hills faded to a dusty tan. As summer crept toward fall, I found myself longing for the rain and dark I had hated in England. I discovered that my neighbors, too, eagerly awaited the first rain of the season. We celebrated together as the sky darkened and the first drops fell. I was learning to be a Californian.

Robin redbreast on a fence

I still ponder why it meant so much, that Christmas morning in England in the 1960s, that a robin sat on the back fence. The field behind the fence was white, the fence wires thick with hoar frost, and the little red-breasted bird made the scene perfect. Finally, I told myself, a ‘real’ Christmas.

I have tried for many years to clarify my feelings about the disconnect between the traditional trappings of the season and my experience of growing up in New Zealand, where the seasons are reversed. My childhood Christmas memories are of summer: the tree laden with oranges in my grandmother’s garden where we hung our presents and picnicked on the lawn; the scent of magnolia blossom outside the church on Christmas Eve.

Also the Christmas cards with their images of snow (which I’d never experienced) and yes, the English robin. I knew about robin redbreast from the old nursery rhyme, but until that Christmas I hadn’t seen one.

Now on the coast of Northern California, I have a different understanding of how to celebrate the winter season. Our multicultural society recognizes many winter festival stories and traditions: the birth of Jesus in a stable, the menorah candles of Hannukah, the Swedish light-bringer St. Lucia, the gift-bringer St. Nicholas (known also as Santa Claus), and many others. The celebration that holds the deepest meaning for me now is Winter Solstice, the return of the light. From summer to winter, I note where on the horizon the sun sets, and how the darkness grows. Even as clouds gather, the place where sun disappears into ocean fogbank moves steadily to the south. When the prevailing westerly wind shifts to the southeast, I know to expect the winter rains. Sometimes a shower or two, sometimes, such as this past week, a prolonged deluge that floods rivers, downs power lines, and closes roads.

Meanwhile, the earliest spring flowers are breaking bud, and over-wintering birds gather hungrily at my feeder: Steller’s jay, spotted towhee, hermit thrush, acorn woodpecker, hordes of white-crowned sparrows. I love them dearly. I am happy that I have learned to understand the connection between the flow of seasons and human efforts to explain them with stories and festivals. And I still have a place in my heart for the memory of that cheery robin redbreast who brightened an English winter.

A season for love (and cake)

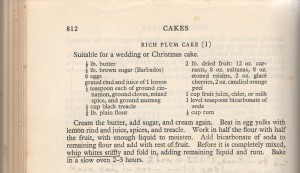

What I loved about living in England as a young woman in the 1960s was the traditions around the holiday season. On foggy street corners in London, vendors with portable braziers sold roasted chestnuts, hot in the hand, but so good. Butchers’ shop windows would fill with huge hams, neighbors’ kitchens be redolent with the aroma of figgy puddings steaming on stove tops. I would pull down the English recipe book my mother-in-law had given me and assemble ingredients for my Christmas cake: an assortment of dried and candied fruit, spices, juice, eggs, butter, brown sugar, treacle, flour, and the all-important dash of rum.

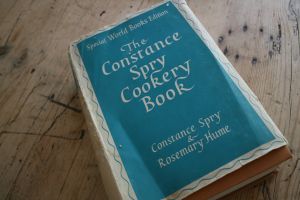

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

Making a proper English fruitcake is a multi-day affair. First, the careful preparation of the tin and timing of the baking so that it doesn’t go dry. My Constance Spry Cookery Book devotes several pages to these matters. Then the making of the cake itself. Several days later, in preparation for icing, the cake is brushed with a warm apricot glaze. My cookbook declares:

The object of this protective coating is to avoid any crumb getting into the icing and also to prevent the cake absorbing moisture from the icing and so rendering it dull.

Next comes the layer of almond paste or marzipan, rolled out like pastry and smoothed on with the palm of the hand. A day or three later comes the smooth base coat of royal icing, made by mixing egg whites and lemon juice with the sugar. When this layer is perfectly stiff and hard the decoration is piped on.

When we moved to California, I continued to make Christmas cake for a few years, until I realized that fruitcake in America is the butt of seasonal jokes and that my lovingly prepared cake sat in the pantry scarcely touched. I am grateful that until his death a few years ago, my late brother-in-law Derek Heckler, who lived not far away, continued to bake and share a splendid traditional cake.

As earth and sun roll toward another pausing time, let us remember dear friends and family members now gone, and reach out in love to those still with us. However you celebrate the season, may it be filled with the traditions you hold dear.

My first cuckoo

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu

Listen to this Medieval rote song

An English oak woodland. Image from Open University on the BBC

My first spring in England, late afternoon in Windsor Great Park. Green-gold light through ancient oaks, the air rich with leaf-mold and violets. A cuckoo calls. I have heard the sound all my life, in music and poems, but never before in the wild.

Listen to the cuckoo calling in this recording from the British Library

As I stand listening, this spring in 1962, something shifts in my thinking. It is as if previously I saw the world through two mesh screens, one named Southern Hemisphere and the other Northern Hemisphere, half a year out of alignment with each other, so that my view was blurred by the moiré patterns their meshes made. The religious festivals my ancestors brought from the northern hemisphere when they emigrated to New Zealand lost their old association with the seasonal cycles of life and death when celebrated in the reversed seasons of the southern hemisphere. In consequence, I felt, even as a child, a subtle sense of having been cut off at the roots, of being, even after several generations, transplanted British.

Images float into my mind. Mid-morning, Christmas Eve, at All Saints Church in Tauranga, NZ. Strewn mounds of flowers deck the chancel steps. The Altar Guild ladies are filling shiny brass vases that stand either side of a red-draped altar. Bronze-purple foliage of copper beech, fans of gladiolus spikes, the tropical exuberance of canna. They add dahlias, roses, bougainvillea until the reds vibrate.

Sunlight through stained glass glitters on the sharp points of holly springs that I strew along the dark wood windowsills, hiding jam jars filled with red geranium flowers. The holly bears no berry here, this time of year, and the carol I hum under my breath echoes in an empty place inside me. Later, at midnight services, the congregation sings of light in darkness and the falling of snow. We emerge to warm air, misty moonlight, and the scent of magnolias. This Christmas is not real, I think to myself. It’s pious make-believe.

Easter: after morning church and family lunch, I gather with siblings and cousins on the porch to smash the Easter eggs we have all been given. Molded of hard sugar, they are pastel pretty, with piped-on decorations of flowers and leaves, the symbols of spring. Having gorged ourselves, we scamper off to scuffle through autumnal leaves.

Cuckoo image from

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

My reading in college, particularly J.G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough, helped me recognize that Christian festivals have pagan roots: the ritual victim dies at planting time; the winter birth is the rebirth of the sun. As the cuckoo calls again, cu-coo, over and over, quietly, the blurred meshes of my hemispheres resolve and I see through: myself and my people bound by tangled apron strings to the life our forbears left, and to the earth itself, an old reality, almost forgotten.

Good old days at the post office

In December of 1962, before there were mail codes or mechanical sorters, I worked for a week at the post office in Windsor, England, helping with the Christmas rush. I mentioned it in letters to parents:

18 Dec. 1962

…Hope this reaches you in time for Christmas – along with the other thousands of tons of mail being posted this week. I know – I have to sort the stuff. I am spending the week working in the sorting room at the post office. Very difficult job! – turning the stamps up the right way as the letters come out of the postbags. Have to work pretty hard, but it’s rather fun – very cheerful, friendly crowd – and good money.

26 Dec. 1962

…I had a very interesting week in the Post Office. Halfway through the week I was promoted to sorting, which was a bit more fun, though harder work than facing up.

Those were the days, before email, Facebook, Twitter and other social media, when the annual holiday greeting card was how one kept in touch with extended family and friends. According to Wikipedia the custom of sending greeting cards has a long history, dating back to the ancient Chinese. The postage stamp was introduced in England in 1840. Cards started being mass produced by the 1850s. From then on, mailboxes became crammed each December with penned good wishes.

Every card and letter had to be sorted by hand. Mechanical sorting, which depended on reducing the address to a machine-readable form, came in a few years after my stint at the Windsor post office: the 5-digit ZIP code was introduced in the U.S. in 1963, and England’s alphanumeric postcode system in 1966.

Communication methods have changed, and fewer greetings now go by “snail mail.” The U.S. Postal Service reports that First-Class Single Piece Mail; that is, mail bearing postage stamps, such as bill payments, personal correspondence, cards and letters, etc., declined by 47 percent in the decade 2005–2014. But that urge to reach out to those we love during the holiday season is still with us.