Archive for the ‘articles’ Category

Stereotypes and misconceptions

When I lived in England in the 1960s it bugged me that, when they learned where I was from, people would typically have one of three responses:

1) They had no idea where New Zealand was.

2) They thought it was part of Australia.

3) They knew of it as that pastoral paradise they’d dreamed of emigrating to when they were younger.

Reading my old notes about coming to England in 1962, I realize that I too had huge misconceptions about what my new home would be like. Here is the account of our arrival:

First view of England – not counting faint views through the foggy channel – picturesque houses of Isle of Wight – only we thought it was Southampton and decided England must be charmingly antique and folksy, with church spires peeping through the trees and glowing green fields running down to the sea. but we were a little perturbed that we couldn’t get our geography right. Fascinated by the light – very soft, still a little hazy after the rain and fog of the day before, but with the sun coming through in pale golden streaks.

Our ship anchored off the Isle of Wight and passengers were sent ashore by tender. We managed to miss the boat train by being held up at Customs – a fuss over a lens Tony had bought in New York. But were well looked after by the railway porters, who rushed to get us into a taxi to catch the same train at the central station. On the way, the taxi-driver casually pointed out the old Roman wall of the town. As we gazed in amazement at something 2000 years old, and taken for granted, we began to realize the sense of history about the place, which confirmed even more the feeling of newness about New Zealand. My notes continue:

As the train pulled out of the centre of Southampton we discovered the slums. Obviously not the worst of the slums, but up till then we haven’t really believed that they existed, although we could mention them matter-of-factly. England from New Zealand looked a golden land, a land of opportunities, a land that housed the rich heritage of the old world. It definitely did not mean rows and rows of dreary brick buildings exactly alike, and behind them rows and rows of exactly similar yards, with blackened paling fences and rubbish tins. But occasionally we recognised the cry of a human spirit – from among the debris would rise a patch of golden daffodils dancing in the pale sun, cultivated by loving hands. And for a time we passed through farmland, with pussy-willow growing fat by the railway track, and small boys ambling cheerfully by hedges. Even one or two thatched cottages and barns, and we felt with a sentimental rush that we really were in England. But as we neared London the houses grew thicker and more dreary, their bricks blackened with smoke and soot, their monotony more grey. But even here people were making the best of their situation with window boxes full of bright flowers.

As well as misconceptions, I had opinions. I was amused to find in my notes that, with no knowledge of English social attitudes and no background whatsoever in urban planning, I laid out an argument about high density housing:

I have not yet resolved the problem of what is the best form of high density housing for such a city. Most people are housed in these old row houses, a monotonous block, but at least with some little bit of ground, however filthy and untidy, that they can call their own. The other alternative seems to be tall apartment blocks in their own parks. The disadvantage of these seems to be that the people shifted into them lose their sense of community – they no longer feel that their home is their castle, for they share it and its services with dozens of other families. I would feel the lack of a bit of ground of my own to cultivate, or just sit in. A semi-public park is all very well, but it gives no opportunity for creative contact with the earth. I have seen a few modern blocks of row houses, some of which are quite pleasant, but others will obviously become the future counterparts of the present monstrosities – pleasing to look at now because they are new, but once the newness has worn off little of artistic value will remain. Others, particularly a small block seen near Primrose Hill, had a cheerful friendly atmosphere that appeared more durable.

Ah, the certitude of youth.

The Rain in Spain and all that

In April 1962, fresh off the boat from New Zealand, I stood on a railway platform in Southampton, on England’s south coast. All around me the sound of voices, English voices. In notes written a few days later, and saved in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

Railway platform – probably much the same as those in NZ, but had a sense of Englishness about it – hard to define, but probably due to the language spoken – correct English accents as if they were the most normal thing – this takes a bit of getting used to. … Here on the Southampton platform we heard the ‘jolly hockey sticks’ manner of speech for the first time. In all cases, it is difficult to distinguish in the mind between the real thing and the caricature which up to now is all we have known. The same with men in bowler hats and umbrellas.

Reading these notes fifty-three years later, I see in them the ambivalences and ambiguities that filled my formative years. Europeans had been in New Zealand for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain, the English, Irish and Scots immigrants brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. For my father and his friends, a man was considered useless unless he was good at working with his hands. An Englishman, especially if he had a “posh” accent, was teased about being a “Pom” and eyed with suspicion until he could prove himself as one of the blokes.

On the other hand, well-spoken Englishwomen dominated the social life of the resort town where I grew up. English bone china teacups clinked in parlors where pictures of thatched cottages might grace the walls, and genteel conversation was made about making the trip “Home” to the old country.

Prejudices about accent can cut both ways. The longer I stayed in England, the more I realized that how one speaks was critically important in that class-bound society. I quickly dropped all the Kiwi slang I ever knew. But, unlike Eliza Doolittle in “My Fair Lady,” I could not get my tongue around the inflections and tonalities that signified “proper” English. My accent slotted me into a pigeonhole labeled Colonial, from which I could escape only by leaving.

Westernesse in the rain

An Aran Island scene on a sunnier day. This aerial photograph by Aongus O’ Flaherty is from http://www.aerarannislands.ie

My first glimpse of the British Isles was the Aran Islands, at the mouth of Galway Bay, where our trans-Atlantic ship stood off to land a few passengers. It was an emotional moment. The destination of our long sea journey at last become visible. Vague romantic dreams faced with reality. I was shocked by the bareness and bleakness of the landscape. Heavy rain was falling, and wind lashed waves onto the shore. The bare rock of the grayish white hills (karst limestone, I later learned) was dotted with tiny scraps of green that glowed brightly in the rain-sodden air. A few white cottages of plain design: four walls and a pitched roof, a door in the middle and small windows at each side.

In notes written at the time, I tried to capture my sense of the place:

Centuries old, yet timeless. Feeling of age and solidity of a way of life that has gone on for centuries – the grimness of it, the few rewards. Can imagine the people to be tough and dour. Weather-beaten faces of seamen who brought the tender out to pick up passengers. No-nonsense faces, with a wry sense of humour.

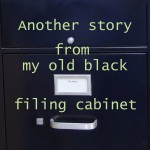

The Lord of the Rings trilogy in its original format as published by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. in the mid-1950s.

From halfway across the world, the reality of the British Isles was also mixed with romantic fantasy. Before we left New Zealand, copies of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, with the device on its cover of Sauron’s eye within the Ring, surrounded by Elvish script, were passing from hand to hand among our friends. As I looked across the sea to this westernmost part of Ireland, I couldn’t help thinking of Tolkien’s Westernesse, the place to which the fairy people set out when life on Middle Earth became impossible for them.

The curtain of rain swept down again. The ship moved on, headed for Southampton, the end of our journey and the beginning of our new life.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Music of the Elysian Fields

Growing up in New Zealand, the Metropolitan Opera House in New York was the stuff of dreams: the tragic drama of the opera plots, the names of the great stars, the LP disks in my mother’s collection played over and over. To actually be there was an extraordinary sensation. “The whole place just breathes atmosphere,” I wrote to my parents, “the opulent decorations of a former era, and the shades of the singers who rose to fame on its stage – portraits of the greatest everywhere. “

Thursday, March 29, 1962 was our last night in New York before my husband Tony and I took ship for England to continue our youthful adventures. My sister Evelyn treated us to the opera tickets as a grand finale to our visit with her. The performance that evening was Gluck’s “Orfeo ed Euridice,” a very quiet, 18th century version of the story, with a happy ending. To quote from the Metropolitan Opera synopsis:

“Overcome with grief and remorse, the poet cries that life has no meaning for him without Euridice (“Che farò senza Euridice?”). Preparing to take his own life, he resolves to join his wife in death. Before he can do so Amor appears and announces that Orfeo has passed the tests of faith and constancy and restores Euridice to life. The happy couple returns to the upper world, where they are greeted by friends, who perform dances of celebration. Orfeo, Amor and Euridice praise the power of love.”

What stays in my memory is the dancing. As I wrote to my parents: “The ballets, particularly in the scene in the Elysian Fields, are really beautiful. I think it is the ballets that really make the opera – the terrific contrast between this scene and the previous one – the Furies at the entrance to Hades – all dressed in torn black tights, writhing and twisting, outlined against eerie red flames.”

Here is a YouTube recording of Gluck’s Elysian Fields ballet music.

If you’d like to learn more about the performers, here is a page from Opera News, March 10, 1962

I also found this March 1962 review by Irving Kolodin in the Saturday Review:

“On the whole, the visual aspects of this ‘Orfeo’ were more absorbing than the aural, for Harry Homer’s settings (of 1938) still provide an atmospheric frame for the action and Violette Verdy (a replacement for the absent Alicia Markova) is an excellent dancer, as is Arthur Mitchell, who shared the place of prominence with her. John Taras designed the choreography, which was theatrically justifying if somewhat showy, in its lifts and leaps, for the repose of the Elysian Fields.”

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

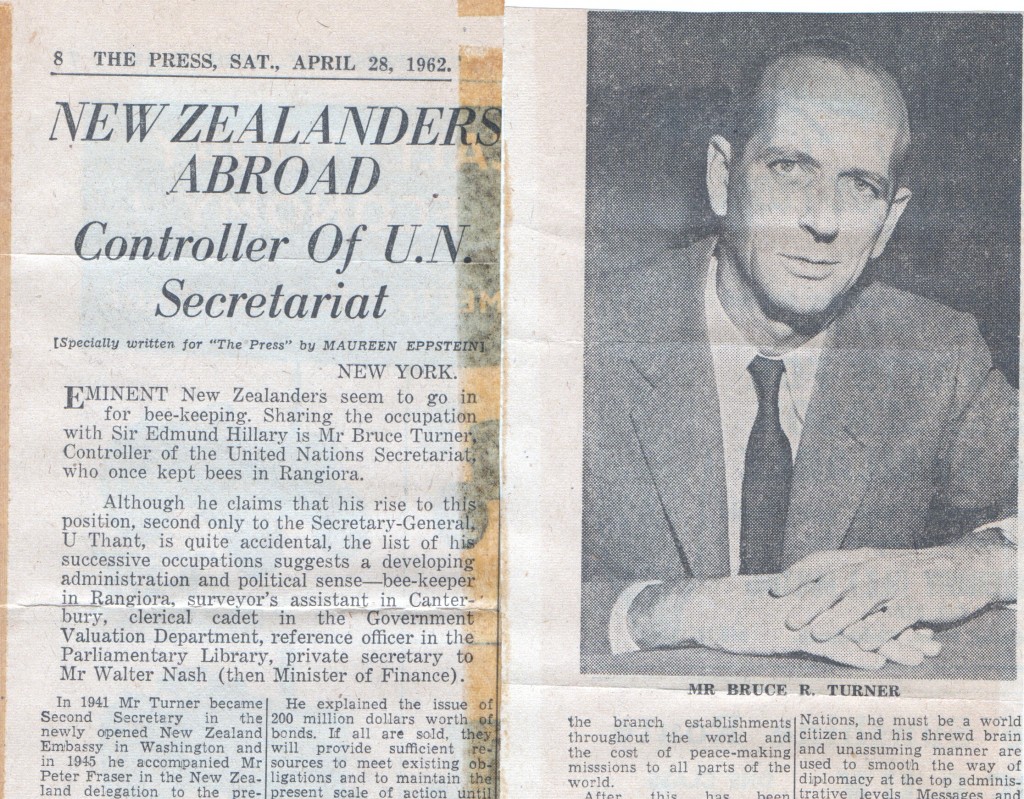

A Kiwi at the Top

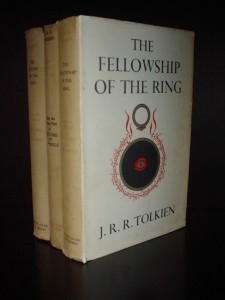

It felt like being in a fairytale. There I was, a country bumpkin on the 37th floor of the United Nations Building in New York, interviewing a man second only to Secretary-General U Thant himself.

When I left my job at The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper, to go abroad in 1962, the paper’s editor handed me a list of names. “These are New Zealanders who have done something interesting with their lives. Track them down and send me back some interviews,” he said.

On the list was Bruce Turner, Controller of the UN Secretariat. In a letter to parents, I described him as “A typical Kiwi c haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

Here’s a transcript of the interview.

1962 Bruce Turner interview

Eminent New Zealanders seem to go in for bee-keeping. Sharing the occupation with Sir Edmund Hillary is Mr Bruce Turner, Controller of the United Nations Secretariat, who once kept bees in Rangiora.

Although he claims that his rise to the position, second only to the Secretary General, U Thant, is quite accidental, the list of his successive occupations suggests a developing administrative and political sense—bee-keeper in Rangiora, surveyor’s assistant in Canterbury, clerical cadet in the Government Valuation Department, reference officer in the Parliamentary Library, private secretary to Mr Walter Nash (then Minister of Finance).

In 1941 Mr Turner became Second Secretary in the newly opened New Zealand Embassy in Washington and in 1945 he accompanied Mr Peter Fraser [the NZ Prime Minister] in the New Zealand delegation to the preparatory commission on the first session of the new United Nations.

“Here Mr Fraser had the misguided generosity to lend my services to the first Secretary-General, Trygvie Lie, and I haven’t been able to get out of it ever since,” Mr Turner said recently in New York.

Vast Responsibility

On him rests the responsibility for all financial aspects of the organisation’s activities. “And since everything we do involves money, this means, in effect, the whole lot. The position would be comparable in New Zealand to that of the Treasury, the Auditor-General and in some respects the Public Service Commission, all rolled into one. Sometimes I suspect that I don’t know entirely what the job involves myself,” he said.

His department prepares in advance a budget of regular expenditure. This includes the administration of the secretariat in New York and the branch establishments throughout the world and the cost of peace-making missions to all parts of the world.

After this has been approved by the Administration and Budgetary Committee of the General Assembly, commonly known as the Fifth Committee, the money is collected on a quota system, based on the capacity of each member government of the United Nations to pay. This quota is periodically revised by a committee of ten experts.

But for extraordinary expenditures, such as the United Nations Emergency Force sent to the Middle East in November 1956 and the force sent to the Congo in July, 1960, a separate budget is required, although the proportion borne by each country remains the same.

A Major Problem

Here lies one of Mr Turner’s biggest headaches. Certain countries claim that they have no legal liability for their quota of this extraordinary budget. Meanwhile, funds are running low, but the need for maintaining forces in the Congo continues.

He explained the issue of 200 million dollars worth of bonds. If all are sold, they will provide sufficient resources to meet existing obligations and to maintain the present scale of action until the end of 1963.

Mr Turner put the problem in the smoothly rounded language of diplomacy and press statements: “On the success of this bond issue depends the future of the whole organisation and its peace-keeping operations.” He broke off to joke grimly: “Oh well, if it fails, this place will be blown up and I will be out of a job.”

He spread his hands lightly round the pleasant wood-panelled room with its quiet beige and jade upholstery. Heavy curtains hid a view of the East River and Brooklyn in the early evening. On a low table, beside a bowl of spring flowers, a handsome Maori carving gave a hint of the occupant’s country of origin.

“Some day I might retire to New Zealand—that would be the normal procedure for any expatriate New Zealanders,” he said. “It would be somewhere with a warm, mild climate. Tauranga perhaps—that is not too far from my friend in Hamilton who owns a brewery.”

Meanwhile, like all other employees of the United Nations, he must be a world citizen and his shrewd brain and unassuming manner are used to smooth the way of diplomacy at the top administrative levels. Messages and telephone calls continued to pour into his office, telling of Government decisions on the bond issue. The maintenance of forces in the Congo, while still a grave problem, seemed a little more hopeful.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Art stuns like a hammer blow

With gold velvet drapery as backdrop, the newly acquired Rembrandt, “Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer,” stood on an easel in the foyer of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Spotlights accentuated the golden glow of the painting’s surface. As I gazed, I felt a resonance with the feelings of the person depicted, my thoughts drawn into his as if into a dizzying vortex. I was astounded that brushstrokes and pigment could have such power to move me.

I had not seen great art before, except in books of reproductions. I had devoured the collection of large format books in my high school art room, and spent hours browsing the art section of secondhand book shops when I was in college. When we left New Zealand in 1962, Tony and I had as a priority to visit art museums and see the work of artists we admired. But nothing had prepared us for being in the presence of the real thing. Upstairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art we found a whole room of Rembrandts. Dancing down a broad staircase, a whole series of bronze sculptures by Edgar Degas. We saw so many great works we discovered the phenomenon we named “mental indigestion” and wished we had more time in the city so that we could come back. We knew it would take weeks, months even, to absorb all this museum had to offer.

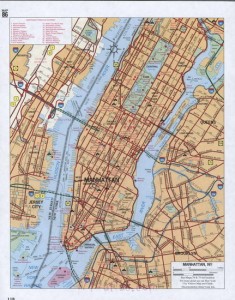

We visited other art museums during this stopover in New York on our way to England. Some we loved, some less so. In a letter to parents I wrote: “Sunday afternoon we went out to The Cloisters, which is right up at the northern tip of Manhattan. This is a religious museum. Parts of the remains of many old churches of Europe have been brought across and incorporated into the present structure, which keeps as closely as possible to the original styles. In a sense it is a success – some of the old fragments of stonework are very fine, and there are some very fine paintings, altar ornaments, and some magnificent tapestries – the highlight of the whole exhibition. But in spite of their attempts to reproduce chapels, all sense of reverence has been lost – the things are a curiousity for the locals to gawp at, and even sacrilegious.”

As I look back on these youthful letters and these memories, I see opinions about what matters to me already forming and clarifying. Many more experiences of the power of art would come in future years: sitting on a bench in a crowded London gallery, weeping over Georges Rouault’s “The Old King;” gazing in awe at the rose window in Chartres Cathedral; feeling the silence of the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Always, enriching these experiences, the memory of that stunning awakening in New York.

Country bumpkins in New York

The friends we were traveling with chose the hotel, the cheapest they could find. It was on W. 46th Street, just off Times Square. Only one thin hand towel in the grungy bathroom. What to do? We called the desk. A maid appeared, to tell us the towels were not yet back from the laundry. In hindsight, a tip might have made towels magically appear. But we knew nothing about tipping; it wasn’t a part of the culture we knew.

Breaking our 1962 journey from New Zealand to England as young married couple off to see the world, Tony and I had disembarked in New York to visit my sister Evelyn, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University in upstate New York. From there the three of us traveled by Greyhound bus to Baltimore to spend a few days with her friends Brian and Jennifer Wybourne and visit Washington, DC.

Driving with the Wybournes back to New York, where we were to board another ship bound for England, we were wide-eyed at our first glimpse of the New Jersey turnpike. In a letter to parents I wrote: “…one of the most famous of the turnpikes – 150 miles of unhindered 6-lane highway. Then navigating the streets of the city – practically all are one-way, which makes it complicated, and you can imagine the traffic.”

The letter continues: “The next morning we went up to the top of the Empire State building – early, before the mist got up. The view from the top is terrific – you can see the whole extent of New York city – which is saying something.” I look back in memory and see the young woman I was, neck stiff from craning upward at rows of skyscrapers that made deep canyons of the streets, mind agog at the level of luxury displayed in store windows. I remember wandering through several of the huge department stores, feeling lost and out of place.

One day we walked to the tip of Manhattan and back, excited to see Wall St. and Greenwich Village, and to walk on Broadway. I wrote: “We were really footsore by the time we reached the hotel, but then we had the big experience of our trip – riding the New York subway during rush hour. That was some experience. We held each other tightly, and shoved with the rest. Sardines in a can had nothing on the train – but you had to make sure you weren’t pulled out with the rush at each station.” Evelyn, who was taking us out to the Bronx to dinner with the family she was staying with, wrote in her letter home: “I deliberately engineered it to be at Grand Central Station about 5 past 5 at night. It was quite an eye-opener for them…”

On each of the other nights we had the new experience of dining in a restaurant of a different nationality, all quite cheap by New York standards, and all in the same block as the hotel – Greek, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, as well as American – hamburgers and doughnuts.

For lunch Evelyn introduced us to automats. I commented: “We found foreign food much more interesting than American – they process it and vitaminise it, and goodness knows what – the result is rather tasteless.”

In future weeks I’ll talk about other aspect of our first visit to New York: the art, the music, the experience of visiting the heart of the United Nations secretariat.

And yes, a few more threadbare towels did eventually show up in our hotel room.

Other people’s weather

An ethereal music filled the air as Tony and I stepped down from the Greyhound bus at Niagara Falls in March 1962, a music so sweet and high it seemed to come from some magical place. I gazed about me. Nothing but bare trees and an almost empty parking lot. A wind that stung my ears. Then I saw them: icicles, many inches long, hanging from every twig and tinkling against each other with every gust.

Growing up in the subtropical north of New Zealand, I did not see snow until I was an adult. Our winters had heavy rain and an occasional frost, enough to whiten the grass and form thin sheets of ice on puddles. But nothing like this: the gigantic falls themselves half frozen and the temperature the coldest I had ever known. Historical records tell me it was probably about 30°F. (though the wind chill factor would have made it seem colder), and that the winter was pretty much a normal one.

We had broken our journey from New Zealand to England in New York to visit my elder sister, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University. As we rode the Greyhound bus upstate to Syracuse, what fascinated me as much as the landmarks my sister pointed out were the piles of dirty snow everywhere. I began to comprehend the northern hemisphere stories I had grown up with, where winter was a time of death and darkness, the weather something to be feared, and the spring thaw a time of great rejoicing.

Having recently passed through the tropical miasmas of Panama, I was also discovering that people could learn to live in places where the climate was not friendly, though the strategies they used to deal with the climate sometimes left us puzzled. In Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for example, where our ship had berthed for a day on its way to New York, we were stunned by the difference between the searing heat outdoors and the air-conditioned iciness inside the big stores.

Tony and I realized then that that we were just starting on the great adventure of learning how the rest of the world lives.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Scrabble and other equatorial diversions

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

After the storms and seasickness of the first week, we had perfect weather: sunny days, calm seas, and just enough breeze to keep things cool. I decided that ocean voyages were not so bad after all.

I had time to dream. When my husband Tony and I carried our bags up the gangplank of the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” earlier that month, bound for New York and then England, I felt I was walking in the steps of my role model, the great New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield, who also went abroad at a young age to pursue a literary career.

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

The Sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out;

At one stride comes the dark

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

I haven’t played Scrabble in years, and don’t remember what happened to our old game set. But this week we bought ourselves a new one. Nostalgia filled my heart as I pulled out from the bag a handful of little wooden tiles.

JVO photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet, which contains 55 years of letters, notes and memorabilia.

Magical Day on a Tropical Island

I have never returned to Tahiti. I prefer to remember it as it was one special day in February, 1962. When I think of that day, a melody from the musical “South Pacific” fills my head.

I have never returned to Tahiti. I prefer to remember it as it was one special day in February, 1962. When I think of that day, a melody from the musical “South Pacific” fills my head.

In a letter to my parents I described coming in to port: “We got up early in the morning, in time to see us come through the passage between Moorea and Tahiti. Moorea is the most enchanted shape of any island – fantastic contorted peaks rising up out of a faint mist, and shimmering in the morning sunlight. … The sea perfectly calm, glassy inside the reef, and a sparkling sunny day.“ We had plans to explore the island by motor scooter, so after wandering around Pape’ete until we found the rental place, we “followed our noses and found ourselves on the coast road.

In a letter to my parents I described coming in to port: “We got up early in the morning, in time to see us come through the passage between Moorea and Tahiti. Moorea is the most enchanted shape of any island – fantastic contorted peaks rising up out of a faint mist, and shimmering in the morning sunlight. … The sea perfectly calm, glassy inside the reef, and a sparkling sunny day.“ We had plans to explore the island by motor scooter, so after wandering around Pape’ete until we found the rental place, we “followed our noses and found ourselves on the coast road.

“Took a turning up into the hills – very steep, narrow winding road up to a lookout point – excellent view over Pape’ete and out to Moorea. Hibiscus everywhere, vivid red, pink, yellow – any colour you can think of. The vegetation is all a bright yellowish green, and the soil is bright red.

“Coming down – discovered that scooter’s brakes were practically nonexistent – slightly hazardous! Continued along the coast road, looking for somewhere to swim, asking the way in our best French. We were agreeably surprized all day that we could understand and make ourselves understood. Of course they speak much more slowly than the French of Paris – hotter climate.

Found a good beach after a ride down a track through a coconut grove – i.e., very large rough boulders – every so often the scooter would jam and we would have to get off and lift her over. Came out between the houses of two Tahitian families. Fishing nets hung along the beach to dry – used them as a changing tent – not that one would need to worry in Tahiti.  Just wallowed in the lukewarm water – crystal clear, and watched the tiny tropical fish nibbling at our toes. Pretty little things, mostly black and white, though some coloured ones, all spotted and striped. Eavesdropped on the Tahitian families at home – fascinating. A very happy, leisurely people – we were amazed with the genuine friendliness we met everywhere.

Just wallowed in the lukewarm water – crystal clear, and watched the tiny tropical fish nibbling at our toes. Pretty little things, mostly black and white, though some coloured ones, all spotted and striped. Eavesdropped on the Tahitian families at home – fascinating. A very happy, leisurely people – we were amazed with the genuine friendliness we met everywhere.  We saw a fishing canoe come in, manned by six men – and with an outboard motor. Also watched women fishing along the shore – four of them splashing about in their sarongs and laughing and singing as they pulled in the net.”

We saw a fishing canoe come in, manned by six men – and with an outboard motor. Also watched women fishing along the shore – four of them splashing about in their sarongs and laughing and singing as they pulled in the net.”

My letter goes on to describe people-watching at an outdoor café back in Pape’ete: “Easy to pick tourists from the ship – they stood out a mile – the footsore look, paler complexions, brand new plaited straw hats – we got one each too, very fine models for roughly 6/- [about $US 0.42] and were very glad of them all day.” Then an evening visit to a tourist hotel for a display of Tahitian dancing. I commented: “The tourist trade is thriving here, especially since the Americans have just finished making a film here, Mutiny on the Bounty. They have sent prices up. The hotel was one of these places that you know are touristy and a bit artificial, but exciting all the same. Guests sleep in native-style bungalows, and the dance floor was also in native style, with carved supporting poles, thatched roof, and open sides. Dimly lit with coloured lights inside bamboo fish traps. Tables both inside and outside on the grass on the shore of the lagoon – that was where we were. All round the edge, kerosene torches on poles to keep away the insects. A huge full moon shimmering on the water, a jetty to wander out and watch the fish. European dancing (Tahiti version) with floor shows – native dancing. The most exciting dancing I have seen. Fantastically fast hula to the urgent throbbing of native drums. Later in the evening the slower, more graceful hula to drums and singing.

“When the show closed – about 1 a.m., there was a general move toward “La Fayette,” which turned out to be a pretty low dive several miles the other side of Tahiti, and was the most terrific entertainment yet. Dim lights, floor jam-packed – mostly pretty well under the weather. Lots of people from the ship – stewards and passengers, with Tahitian girls. No inhibitions – man, what an education! Got back to the ship about 4 a.m. – shore leave finished at five – and wandered round on the wharf, where women were still sitting patiently at souvenir booths – they had been there all day. Spent our few remaining coins on postcards, etc. Many of the passengers waited up to see the boat out, but we piked and went to bed. Very hard to say goodbye to the place.”

In closing my description of the day, my first in a country other than New Zealand, I wrote: “We found it rather difficult getting used to being tourists – you feel so brash and raw, and totally ignorant, and tolerated by the local population mostly as a useful source of income. I think I would much rather go to a place to live for some length of time – it would give you a much better idea of what it is really like. We were lucky in getting a glimpse of Tahitian families about their ordinary life – that I think was the best part of the whole day. But it was only a tantalising glimpse – enough to whet the appetite.”

In closing my description of the day, my first in a country other than New Zealand, I wrote: “We found it rather difficult getting used to being tourists – you feel so brash and raw, and totally ignorant, and tolerated by the local population mostly as a useful source of income. I think I would much rather go to a place to live for some length of time – it would give you a much better idea of what it is really like. We were lucky in getting a glimpse of Tahitian families about their ordinary life – that I think was the best part of the whole day. But it was only a tantalising glimpse – enough to whet the appetite.”

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.