Archive for the ‘articles’ Category

Hurricane at Sea

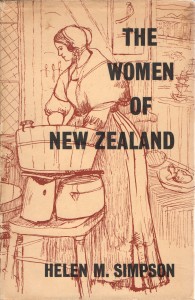

We skirted a hurricane (known as a cyclone in the South Pacific) for the first several days after my husband Tony and I left Wellington, New Zealand, bound for New York on the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt.” For most of that time I lay on my bunk, so seasick I wished I were dead just to get the misery over with. In a letter to parents I scrawled: “Mountainous heaps of water piling up all over the place, wind changing direction all day …Steady old JVO bobbing around like a cork. Thank goodness I have got my sea legs at last – after the first few days of utter misery in a very stuffy cabin. Am still on a largely dry bread and water diet – lost a terrific lot of weight. But have been reading Women of New Zealand today and decided that my lot is not too bad after all. What those women had to put up with on their voyage out to NZ makes me feel rather ashamed of myself.”

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The Ship “Kenilworth” Outward Bound for New Zealand. An illustration in Helen M. Simpson’s The Women of New Zealand, it is a reproduction of a painting by J.C. Richmond, now in the possession of the National Art Gallery, Wellington.

An early chapter describes conditions on board the emigrant ships for the four- to six-month journey from the British Isles to New Zealand. Simpson comments: “Cramped quarters ashore are difficult enough to deal with; at sea, when with every lurch of the ship ‘all things animate and inanimate’ were hurled about, children and chairs in terrifying and noisy confusion …”

Our quarters on the JVO were certainly cramped. Our lower-deck cabin had two bunks and a tiny washbasin in a space so narrow we had to take turns getting dressed. Outside in the corridor, the airless heat was rank with smells from the nearby galley. But unlike those early emigrants, we didn’t have to cook for ourselves, or bring along our own cabin furnishings.

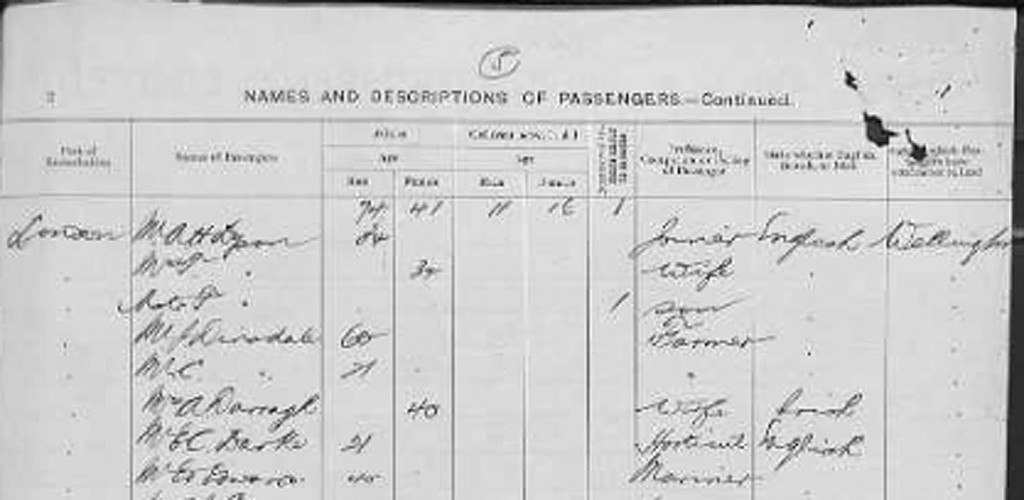

I think of my own ancestors who braved the outward journey. A hundred years before Tony and I walked up the JVO’s gangplank, my newly-married great-great grandparents, Bernard and Sarah Donnelly, set out from County Leitrim in Ireland to join hundreds of other Irish immigrants on the New Zealand goldfields. My paternal grandfather, Charles Dinsdale, emigrated from Yorkshire, England in the early 1900s. By then steam had replaced sail, but he would have set out for his new life half-way across the world with the same sense of adventure.

In her book, Simpson tells of a shipboard fire, when passengers & crew took to the lifeboats. A woman passenger wrote that, when told of the fire, ‘I folded up my knitting, put on my bonnet and shawl, and went up.’ Simpson comments: “So figuratively hundreds of other women folded up their knitting, and, putting on bonnets and shawls, quietly faced these and other perils, and all the acute discomforts of the long voyage to the new land where their hopes rested. Dangers and discomforts were accepted without fuss.”

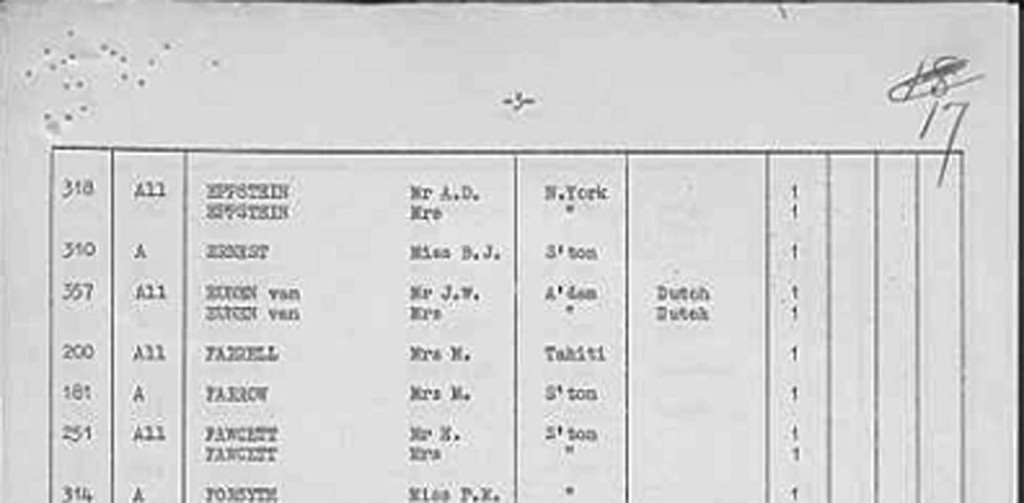

Passenger list for the SS “Corinthic” 1904. The 21-year-old C. Dinsdale (fifth name down) is probably my grandfather. From https://familysearch.org

Simpson’s standard of appropriate behavior is typical of the New Zealand society I grew up in, where we were expected to just deal with whatever hardships came our way. This is why I felt so chagrined for feeling sorry for myself.

Passenger list for the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” 1962. Our names are at the top of the page. From https://familysearch.org

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The End of a Great White Ship

The memoirist Judith Barrington and I have a ship in common. Her memoir Lifesaving has at its center the cruise ship “Lakonia,” which departed Southampton on December 19, 1963, on a Christmas voyage to the Canary Islands. Three days later, a fire broke out. In the ensuing confusion and panic, a small group of passengers, including Judith’s parents, were left stranded without lifeboats and drowned.  Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

On February 13, 1962, the previous year, my husband Tony and I left New Zealand on that same ship. At the time her name was the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt,” of Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN), also known as the Netherland Line. It was not quite her last round-the-world voyage under this flag; the maritime historian Reuben Goossens notes that her final departure from Wellington, NZ was in January 1963.

“What was it like on board?” Judith asked me. “I know my parents were on a cruise ship, but I can’t get a picture in my head of those staterooms or of being on that deck.”

I told her as best I could of the richly carved dark wood paneling that decorated the staircases and staterooms. Reuben Goossens notes that the décor was the work of famed Dutch artist Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945) and sculptor Lambertus Zijl (1866-1947). Lion Cachet “took a great delight in using some of the most exotic timbers and then mixing them with a range of materials, from marble, polished shell to tin and other unique materials. Décor throughout the ship reflected the colonial links between the Netherlands with the Far East.” Lambertus Zijl created many fine sculptures and reliefs that were to be found throughout the ship.

Cover of a JVO dinner menu. We collected and framed several of these, each showing a different bird.

Tony and I also had the sense of being on a ship with a long history. The JVO, as we lovingly called her, was launched in 1929, and was one of the most luxurious ships to be placed on the international trade route to the Dutch East Indies. She was requisitioned as a troop ship during world War II. After the war, she brought large numbers of British and Dutch immigrants to New Zealand under a government-sponsored program that provided free or assisted passages.

Refitted as a one-class cruise ship in the late 1950s, the JVO offered round-the-world and trans-Tasman cruises. Competition from airlines was by then reducing the demand for ships as a standard mode of passenger transport across seas, though airfares were still way beyond the means of most young New Zealanders. We obtained a lower level berth on the JVO for about $160 each. According to a 1963 Pan Am schedule an airline ticket from Auckland to London would have cost about $900.

So the JVO was sold in March 1963 to the Greek Line, and renamed the “Lakonia.” The cruise on which Judith Barrington’s parents perished was her maiden voyage under her new flag.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

As Godwits Fly

Godwits landing on the Motueka, NZ sandspit after their migration from Alaska.

Image from http://blog.doc.govt.nz/tag/motueka/

When asked why so many of us travel abroad, most Kiwis will respond that our birth country is a long way from anywhere and we want to see what the rest of the world looks like. The iconic image for such a journey is the godwit, a mottled brown wading bird with a long upturned bill that arrives around mid-September and spends the New Zealand summers foraging in mudflats and marshes. As the southern hemisphere air turns autumnal, godwits flock on sand spits and set off on their annual migration to another summer. They fly non-stop, nine thousand miles north to their breeding grounds in Alaska and Siberia. The mysterious compulsion for this incredible journey captured the imagination of early New Zealand writers.  Robin Hyde, in her 1938 novel The Godwits Fly, first offered the metaphor: Most of us here are human godwits; our north is mostly England. Our youth, our best, our intelligent, brave and beautiful, must make the long migration, under a compulsion they hardly understand.

Robin Hyde, in her 1938 novel The Godwits Fly, first offered the metaphor: Most of us here are human godwits; our north is mostly England. Our youth, our best, our intelligent, brave and beautiful, must make the long migration, under a compulsion they hardly understand.

A decade later, the poet Charles Brasch would write:

Remindingly beside the quays the white

Ships lie smoking; and from their haunted bay

The godwits vanish towards another summer.

Everywhere in light and calm the murmuring

Shadow of departure …

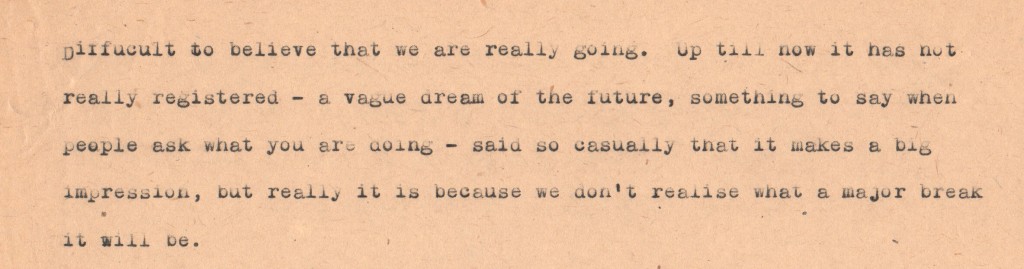

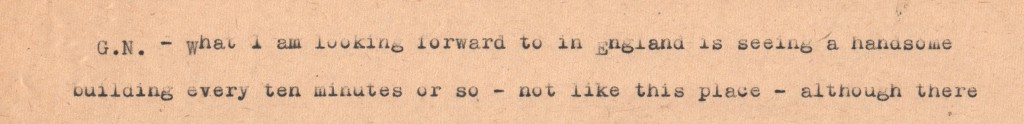

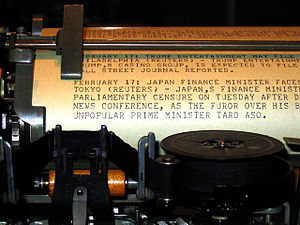

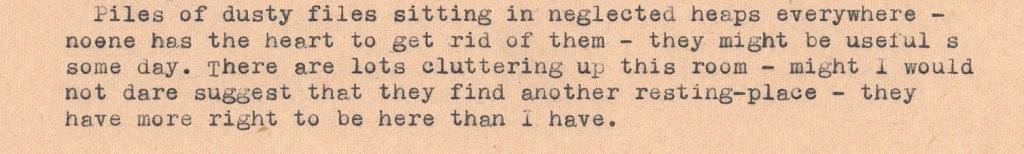

Among my notes in my black filing cabinet is something I must have typed not long before my husband Tony and I left for England:

Pinned to that sheet of 9×6” newsprint (which we reporters used at The Press to type up our stories) is another with this comment from a friend:

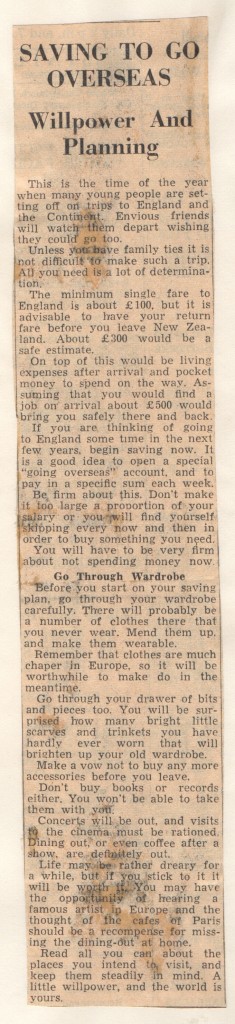

And in my clippings from The Press scrapbook is this advice column. The savings amounts I suggested are in New Zealand pounds, which were each worth US $1.40 in 1961. Even for the time, they were wildly optimistic, as we discovered when we arrived in London.

And in my clippings from The Press scrapbook is this advice column. The savings amounts I suggested are in New Zealand pounds, which were each worth US $1.40 in 1961. Even for the time, they were wildly optimistic, as we discovered when we arrived in London.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Inside a 1960s newspaper office

In graduate seminar at the University of Canterbury, Professor Neville Phillips fixed me with a stern eye as he returned my latest effort. “You are getting through your history papers, Miss Dinsdale, on your writing style, not on your knowledge of history.” I flinched, and worried. Graduation was coming up, and I planned to apply for a job on The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. Within the next week or two I needed to ask him for a letter of reference. Not only was Prof. Phillips head of the history department, he was a former newspaperman himself, and still had deep connections at The Press.

I needn’t have worried. Not only did he write me a nice reference, he also penned a personal note to the paper’s editor, Arthur Rolleston (Rollie) Cant, that opened the door to my dream job.

Press Building, Cathedral Square, Christchurch, NZ. Photo by Michael Whitehead from

http://www.nzine.co.nz/features/150years_the_press.html

I had known since childhood that writing was what I wanted to do. Movies about newspapers such as While the City Sleeps (1958), Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) and Ace in the Hole (1951) filled me with fantasies about the drama and excitement of the reporter’s life. Here was my chance to prove myself.

I loved working at The Press. A great Gothic pile on Cathedral Square, in the heart of Christchurch, the Press Building was a newspaper office out of one of those Hollywood movies: a cavernous newsroom that smelled of newsprint and dust, where telephones jangled, the chief reporter barked commands and the urgent clatter of the Teletype machine signaled a breaking story somewhere in the world.

Picture of Merganthaler linotype machines in a compositing room from the archives of the Nieman Foundation http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/

Sometimes I would be sent on an errand out back to the compositing room, a shadowy cave where enormous Mergenthaler Linotype machines made a deafening clatter. Deeper into the heart of the building, the throb and rumble of the great press itself, and the bustle of loading trucks in the small hours of the morning for long distance runs. When The Press celebrated its 100th anniversary in May 1961, its circulation was 62,000, with subscribers throughout the South Island.

It felt glamorous to work late into the evening, rushing back from meetings to meet the deadline for next morning’s paper. I shared dreams with the other young reporters, all of us with a few scratched notes tucked away for what each of us was sure would be the Great New Zealand Novel. We all had the sense of being part of an old tradition.

Among my notes I found this description of the office, written in 1960. Christchurch at that time was a sleepy provincial city of 193,000 people, and exciting news stories didn’t happen all that often.

I described the office as a jumbly assortment of rooms, all dirty and uncared for, and with space saving nonexistent.

I particularly appreciated my desk in the women’s department, by a window where I could gaze out across Cathedral Square. I’ve written about this view in an earlier post.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Cooking for 120 in a remote fishing camp

The Curious Cove camp, now known as Kiwi Ranch. It looks much the same as when I worked there in the late 1950s.

If you take the ferry from Wellington, New Zealand across Cook Strait and through the Marlborough Sounds to Picton, at the northern end of South Island, you will sail past the entrance to Curious Cove. At the tip of that narrow inlet is the tiny fishing camp where I worked through all my college vacations. Reachable only by boat, Curious Cove was a magical little world. The job, passed down through word of mouth by University of Canterbury women students, was perfect for this impoverished student, with board and lodging provided, nothing but a tiny tuck shop to spend money in, and a nice paycheck at the end of the season. I started off as a kitchen hand and was later promoted to second cook.

The guests, about 120 at a time, would come in for a couple of weeks. We would feed them a full breakfast, then scramble to pack lunch sandwiches for those going out fishing. Those who stayed behind got freshly baked scones with their mid-morning tea, and a salad and cold cuts lunch. By late afternoon, when the launch, “Rongo” hove into view with Charlie the skipper at the helm, the kitchen crew was already at work on the evening meal. It would be plain, traditional New Zealand fare: a roast with gravy and several vegetables, plus a dessert such as apple shortcake with custard.

Here’s a classic New Zealand apple shortcake recipe.

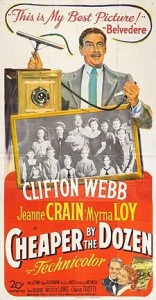

Almost everything was made from scratch. The 1950 movie Cheaper by the Dozen, the story of time and motion study experts Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and their twelve children, was as big a hit in New Zealand as it was in the U.S. Following the Gilbreths’ methods, the Curious Cove kitchen crew, being university students, amused ourselves by figuring out more efficient ways to do things.

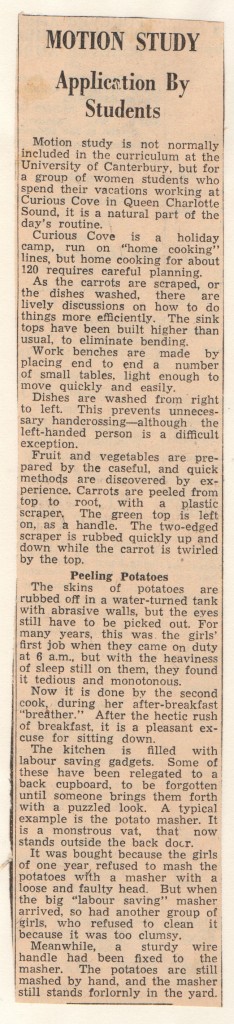

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

How I scooped the sports department

Chat with famous race car driver’s mother

Bruce McLaren in the 1969 German Grand Prix. Photo by Lothar Spurzem, via Wikimedia Commons

Getting the interview was easy. The mother of race car driver (and later designer) Bruce McLaren was my Great-Aunt Ruth, whom had known since I was a kid.

In January 1961 my cousin Bruce was back in New Zealand after an impressive debut on the Formula One circuit, where he had joined his mentor Jack Brabham on the Cooper racing team. In December of 1959, at the age of 22, he had become the youngest-ever winner of a Formula One race, capturing the U.S. Grand Prix at Sebring. He became a star overnight.

Here is a Pathé newsreel clip from that race.

The following year, Bruce came in second only to Brabham in the standings for the Formula One World Championship. Understandably, all New Zealand was agog.

Knowing via family that Auntie Ruth and Uncle Les planned to be in town to act as staff for Bruce as he worked the New Zealand racing circuit, I arranged to visit them at their hotel. Perched on the bed with our cups of tea, my aunt and I settled in for a cosy chat. Auntie Ruth was a great raconteur, and since I already knew the family history, it took little prompting on my part for her to re-tell her best stories.

The interview ran much longer than usual, but the editors at The Press published it in full. The day it was published, almost all the men from the sports department and the general reporting pool stopped by the women’s department to congratulate me. “How on earth did you get that interview?” the sports editor asked. I just smiled.

Bruce went on to establish Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Ltd. Unfortunately, in June 1970, he was killed while testing a McLaren CanAm car at his company’s site in England. His company lived on and today enjoys the reputation as one of the world’s foremost racing teams. Bruce was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall Of Fame in 1991.

I’ve appended a transcription of the interview with Great-Aunt Ruth.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

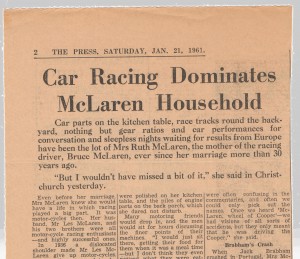

The Press, Saturday Jan 21, 1961

Car Racing Dominates McLaren Household

Car parts on the kitchen table, race tracks round the backyard, nothing but gear ratios and car performances for conversation and sleepless nights waiting for results from Europe have been the lot of Mrs Ruth McLaren, the mother of the racing driver Bruce McLaren, ever since her marriage more than 30 years ago.

“But I wouldn’t have missed a bit of it,” she said in Christchurch yesterday.

Even before her marriage, Mrs McLaren knew she would have a life in which racing played a big part. It was motor-cycles then. Her husband, Mr Les McLaren, and his two brothers were all motor-cycle racing enthusiasts – and highly successful ones.

In 1936 a dislocated should made Mr Les McLaren give up motor-cycles. Two or three years later he became interested in racing cars.

World War II ended all racing, but after the war Mr McLaren did a great deal of club work in hepolite trials and hill climbs.

Bruce, aged eight at the time, was interested even then, and two years year, when he entered Wilson Home with a hip disease, he insisted on regular reports from his father.

Muddy Clothes

After Bruce came out of the home, at the age of 12, he spent 12 months with a hip sling and crutches. Football was out, much to his disappointment, but Mrs McLaren still found her share of muddy clothes to wash when Bruce and his father went on hill climbs and mud trials.

Bruce’s first car was an Austin seven, which he acquired and “hotted up” at the age of 14. That was the end of Mrs McLaren’s garden. Too young for his driver’s licence, Bruce could not drive it on the roads, so he made a race track round the backyard and through the orchard. “No garden, and no branches left on the trees, either,” Mrs McLaren recalled.

Every visitor to their Remuera home was initiated to the track, and had to endure a hair-raising and head-ducking ride round the course.

From driving-licence age on there was a series of gymkhanas, hill climbs and mud trials, Mrs McLaren said. “It was a great thrill seeing him win—we used to go everywhere with him.”

Parts in Kitchen

When Bruce was 16 his father acquired an Austin Healey, which had something special about its engine. Although Mrs McLaren has picked up a great deal of motoring jargon, she cannot remember exactly what it was. All she remembers is the gloating and loving care with which the parts in question were polished on her kitchen table, and the piles of engine parts on the back porch, which she dared not disturb.

Many motoring friends would drop in, and the men would sit for hours discussing the finer points of their machines. “I would just sit there, getting their food for them when it was a meal time—but I don’t think they even noticed what they were eating,” said Mrs McLaren.

By this time both Bruce and his father were driving the Austin Healey. There came a day when the son drove it faster than the father. that was the day when the father decided it was about time he quit.

Waiting for News

The news that Bruce had won the driver-to-Europe award caused great excitement in the McLaren household. Later, when he had gone, came the terrific strain of waiting for results.

“I just lived on my nerves the week-ends he was racing,” said Mrs McLaren. Always at the back of her mind was the fear of a crash. “We have great faith in Bruce’s driving ability, but there are always things beyond his control. But he has not had an accident yet—touch wood.”

The McLarens waited anxiously for the first B.B.C. news in the morning, since the results of the championship races were always announced, and the news would come faster than a cable.

Visit to Europe

Two seasons ago, Mr and Mrs McLaren went to Europe and followed Bruce around the championship circuit. “We had a wonderful time—the racing fraternity accepted us as one of themselves, and looked after us wonderfully,” said Mrs McLaren.

During the races in New Zealand Mrs McLaren acts as lap scorer, but this was Mr McLaren’s job on the European tour. Mrs McLaren’s job was to stand by with wet towels and warm pullovers.

With the wives of drivers and team managers, she would go shopping and sightseeing in the towns of Europe. “Usually someone in the party would speak the language, which helped a lot,” she said.

Language difficulties often caused panics on the racing circuits. “The turns of phrase were often confusing in the commentaries, and often we could only pick out the names. Once we heard ‘McLaren, wheel of Cooper’—we had visions of all sorts of accidents, but they only meant that he was driving the Cooper,” she said.

Brabham’s Crash

When Jack Brabham crashed in Portugal, Mrs McLaren was with his wife Betty in the pits. “It was dreadful—it was only half-way through the race, and we had to wait till the end of the 72 laps to get across the track to find out whether he was all right.”

And the end they dashed across the track, jumped into Bruce’s car and to the hospital, where they found after much difficulty and confusion that Brabham was not hurt, but was being kept under observation.

On another occasion in France, when the temperature was 96 degrees in the shade, and 136 degrees on the race track, Bruce came into the pits after the race badly cut with flying stones.

Now Mr and Mrs McLaren wait through the year for the few crowded weeks when Bruce is home. “It makes up for all the time he is away,” said Mrs McLaren. The house is always full of drivers and friends, and is besieged by young autograph hunters.

“It’s very hectic, but very exciting. I wouldn’t miss it for anything,” said Mrs McLaren of her life as mother of a racing car driver.

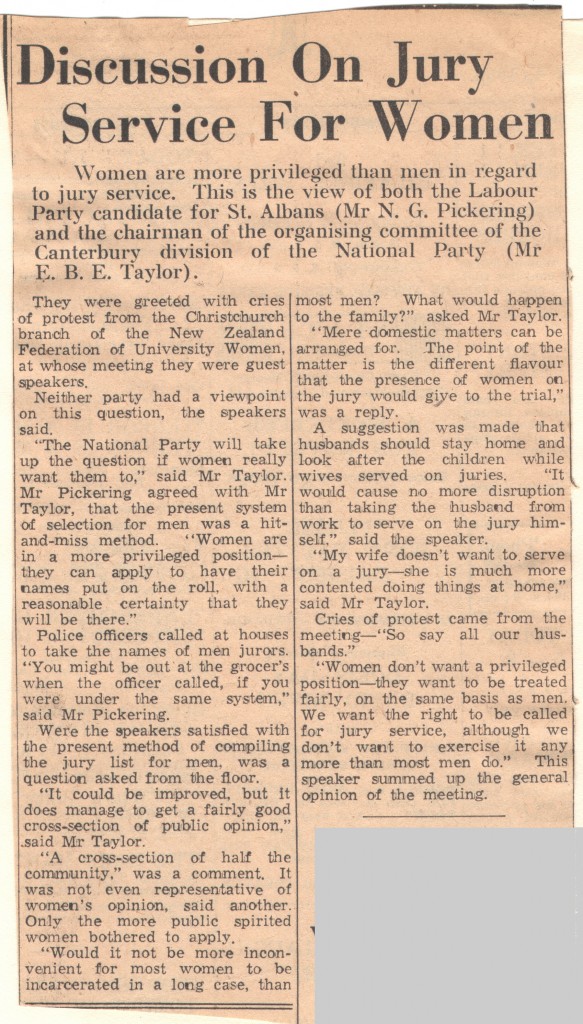

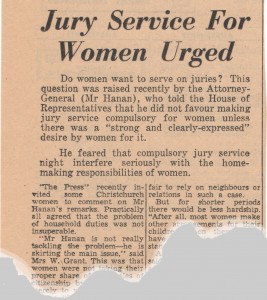

Jury Service for Women

We were a subversive bunch in the Women’s Dept. of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper, even though the editorial stance of The Press was socially and politically conservative. In the early 1960s a big issue for women was the right to serve on juries on an equal basis with men. Until 1942, New Zealand women were denied the right to sit on juries, and even after that date, they had to apply to have their names put on the rolls. Only the most civic-minded women, referred to in some quarters as battleaxes and stickybeaks, volunteered to do so. The official view was that compulsory jury service might interfere seriously with the home-making responsibilities of women.

I remember the glee with which I returned to the office from a meeting of the Christchurch branch of the New Zealand Federation of University Women and regaled my colleagues with the drubbing the guest speakers, two male politicians, received concerning this attitude.

I followed up with a survey: Was there a “strong and clearly expressed” desire by Christchurch women for this equality of status? I’m probably guilty of compromising the survey’s objectivity by giving prominent coverage in my report to a woman with strong egalitarian views, but am comfortable my conclusion is valid:

A petition to Parliament in 1963 resulted in a compromise: the Juries Amendment Act of 1963 made women liable to be included in the roll in the same way as men, but gave a woman an absolute right to have her name withdrawn on request. This right was cancelled in 1976. Jury service for men and women then became completely equal.

NOTE: The issue of jury service for women in the United States followed a similar trajectory, though complicated by variations among states. In 1979 (three years after New Zealand) the U.S. Supreme Court overturned automatic exemptions for women.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

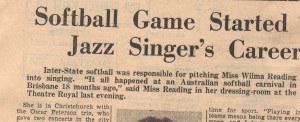

Backstage with Wilma Reading

When Wilma Reading and I stood in the wings watching the Oscar Peterson Trio perform in Christchurch’s Theatre Royal on January 31, 1961, we were two very young women over-awed by the glamour of our situations. Being backstage as a newspaper reporter was new to me: the blazing lights and deep shadows, the flats with their hanging ropes, the smell of dust, the stagehand snapping at us to keep our voices down. For Wilma it was the experience of being abroad for the first time, and performing with world-famous musicians. “I was scared when I knew I was coming. I am still scared when I go on to the stage. But I guess it will always be like that.”

When Wilma Reading and I stood in the wings watching the Oscar Peterson Trio perform in Christchurch’s Theatre Royal on January 31, 1961, we were two very young women over-awed by the glamour of our situations. Being backstage as a newspaper reporter was new to me: the blazing lights and deep shadows, the flats with their hanging ropes, the smell of dust, the stagehand snapping at us to keep our voices down. For Wilma it was the experience of being abroad for the first time, and performing with world-famous musicians. “I was scared when I knew I was coming. I am still scared when I go on to the stage. But I guess it will always be like that.”

Here is a 1961 audio clip of the great Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson and his trio.

Only eighteen months previously, Wilma Reading was a typist in an office in Cairns, North Queensland, Australia who played softball, hockey and basketball in her leisure time. She made the State team for a big softball carnival held in Brisbane. “On the last evening of the carnival, the softball teams had a get-together in a coffee lounge. Someone persuaded me to get up and sing for them, to add to the fun.”

Only eighteen months previously, Wilma Reading was a typist in an office in Cairns, North Queensland, Australia who played softball, hockey and basketball in her leisure time. She made the State team for a big softball carnival held in Brisbane. “On the last evening of the carnival, the softball teams had a get-together in a coffee lounge. Someone persuaded me to get up and sing for them, to add to the fun.”

Among the patrons of the lounge that evening was the leader of a Brisbane jazz band, who invited her to come and sing for the band. “I had to go home and talk it over with my parents, and they let me go.”

Engagements at a Brisbane hotel led to others in nightspots in the city. Later she went to Sydney, where she signed a five-year contract with a recording company. They are all popular songs. “I prefer jazz, but the company prefers popular tunes, as they sell better.”

In this 1960 video, Reading sings one of the currently popular tunes, “My Little Corner of the World”

Wilma Reading sings “My Little Corner of the World”

Future plans were a little vague, she told me. “I don’t think I could go back to being a typist, although I guess I could if I had to.” America and perhaps Hollywood figured fairly prominently in her dreams. “Still, there’s plenty of time and I have a long way to go.”

Wilma Reading went on to a 40-year career performing with major jazz musicians and on television. She was the first Australian to appear on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, had a residency at New York City’s Copacabana nightclub, and toured with Duke Ellington.

There’s a long and fascinating transcript of a TV interview with her at

http://www.abc.net.au/tv/messagestick/stories/s3224613.htm

As we stood in the wings that January 1961 evening, she confided that her main worry was how she would get on with the famous Oscar Peterson Trio. “Many musicians have no time for vocalists, but I have found them wonderfully kind and helpful. They are very natural and friendly, and very good to work with. They have given me a lot more confidence than I had before. Aren’t they amazing?” she whispered as the three imposingly large black men pulled sweet sounds from piano, bass and drums.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

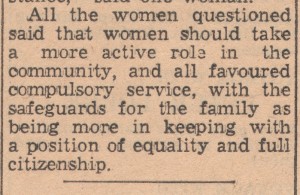

Women’s Lives in 1960s New Zealand

New Zealand social mores were clear when I was growing up in the 1940s and ‘50s: a woman’s place was in the home, taking care of husband and children. A few women (like my mother-in-law) worked after they had children, but the job options were few.

The staff at Christchurch’s The Press newspaper was overwhelmingly male. When I started in 1960, there was only one other woman reporter, besides myself, in the general reporting pool. A vacancy occurred in the Women’s Department, secluded in a separate little office down the hall. The other woman reporter, older and wiser about gender issues, adamantly refused to take it. I didn’t want to go either. I was having a ball scouring the big city hotels for interesting overseas visitors, interviewing artists, musicians and others with fascinating careers and histories. But I was not given a choice. Fortunately the women’s page editor, Tui Thomas, was sympathetic to my lack of interest in fashion and the social scene, and set me to reporting on meetings of various organizations focused on women and families.

I cringed when I first re-read this clipping from my scrapbook, with its sexist stereotypes. Looking more carefully, I sense the speaker’s unease. By the early 1960s, change was in the air. I don’t remember who Mrs Holmes was, but I imagine her as an older woman struggling to reconcile traditional values with the emerging demand by a younger generation of women for an expanded role in the world outside the home. I’ve appended a transcription, in case you have trouble reading the old newsprint.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The Press, March 28, 1961 (transcription)

Importance of Maintaining a Balance in Family Life

“Do we find ourselves so engrossed in outside-the-home activities that we only think of our husband’s meals and his clean socks?”

This question was put to women members of the Christchurch Parents’ Centre last evening by Mrs Helen Holmes in a talk on “Man-Woman Relationships in Family Living.”

Mrs Holmes warned of the pitfalls facing the housewife with too many interests apart from her family, and emphasized the importance of maintaining an even balance in her enthusiasm for interesting activities and her role as a wife and mother.

“In New Zealand today the woman does seem to be the focal point of the family,” said Mrs Holmes. “The man has to a certain extent lost his aloof position as head and dictator to the family. In some cases he is not even the sole provider—the breadwinner. The pattern of family life has changed vastly, and out of the pattern arises all sorts of complicated factors that have to be taken into account if we are to see ourselves as we are.”

The list of a woman’s activities in and outside the home was a formidable one, often including home decorating, gardening, sport, a part in community affairs, reading and entertaining.

“When do we spend time with our husbands?” asked Mrs Homes. “With the woman rushing madly at six things at once and the man working hard at his job and being a general handyman at home, when have either of them the time to contemplate the situation and enjoy each other’s company?”

Mrs Holmes said that a woman must be able to remain feminine—as she was when her husband married her. “A woman is first a wife and partner to her husband. A husband must be able to find peace and relaxation in his home, though providing an atmosphere of peace can be a full-time job for a woman.”

For a woman, life was full of opportunities and all of them interesting. But she would need a good deal of physical, mental and emotional stamina to pursue them all. This applied also to all the things a woman had to decide for herself, by herself, decisions which could bring feelings of insecurity and uncertainty.

In this situation, it was sometimes hard for the woman to accept her dependence on her husband, and might be the cause of a lot of her difficulties. It was hard for her to strike the balance between her natural dependence and her new-found independence.

“We must remember that our husbands have this independence too,” said Mrs Holmes. “There will be many who don’t wish to be involved with feeding time and nappy changing, no matter what the books might say. We must realize this and respect it. There will be many husbands who resent the interests a woman may wish to pursue outside her home. there may be many wives who find themselves frustrated at the prospect of so many interesting things to do and so little time and energy to spare for them.

“There are so many pitfalls. The man is no longer the single-minded dictator, sure of his authority, the woman is no longer his willing servant who only employs roundabout methods for getting her own way, the children are no longer seen and not heard. The role and status of each member of the family are no longer clearly defined and accepted.

Dolphins of Yesteryear

A 55-year-old news clipping brings back memories

An old black metal filing cabinet sits in my cluttered attic. Stuffed into its four drawers are fifty-five years of my stories, some published, most not. Sooner or later someone will have to dispose of all the dog-eared pages and travel-worn manuscript boxes. In the meantime, I’ve set myself a little project for this blog: go through the files and find pieces of my past that you, my readers, might find interesting.

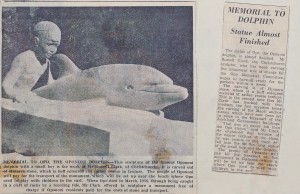

Here’s one, to start us off. On January 6, 1960, I was fresh out of college, and this was my first day on the job as a cub reporter at The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. My boss, the city editor, handed me a four-year-old clipping about the death of Opo, a bottlenose dolphin who chose to join children at play in the surf at Opononi, a beach settlement in the Northland region. The grieving residents had commissioned a statue. “Here, update this story,” he said. “The sculptor lives in Christchurch. His phone number’s in the book. I’ve heard he’s nearly finished.”

I had a pleasant conversation with Russell Clark, the sculptor, who was making the sculpture free of charge as his tribute to Opo. It is of Hinuera stone, which is buff colored and coarse in texture. The sculpture was indeed nearly finished, and would be shipped to Opononi the following week. I was so proud when my little story appeared exactly as written, along with a nice photograph, in the next morning’s edition, having survived unscathed the eagle eyes of The Press’s copy editors, gruff eminences who ruled from a curved dais in back of the press room.

I did not meet Opo, but have my own dolphin memory. We were returning from a family vacation on Tuhua, an island offshore from Tauranga. The day was brilliantly sunny, the launch was bouncing through waves, and I had just learned that I’d been awarded a national scholarship to attend university. A school of dolphins surrounded the boat. Leaping joyously through the waves, they escorted us back to land. As I stood at the bow, I felt like a princess.