Archive for the ‘domesticity’ Category

Death of a Christmas Tree

We’d bought the young spruce in a fit of environmental consciousness when we still lived in Cupertino, CA. and it served as our Christmas tree for several years. In 1973 it survived our move to Santa Barbara, carefully bolstered in the U-Haul truck so it wouldn’t get smushed. It put up with a year or so of Santa Barbara sunshine, had even come into the house one holiday season. But that year, 1975, the temperature spiked into the 80s just after Christmas and hot sun streamed into the house. I was too busy with holiday guests and activities to think about moving the tree outside into the shade, so it stayed inside far too long. By the time we disburdened it of its decorations and lugged it back outside, the damage was already done. Months later, when I could no longer bear to look at pathetic brown needles, I removed it from its pot. The roots were tightly bound around each other.

One received wisdom is that you buy a potted tree for the holidays, then plant it in your garden. But this is not realistic if the tree’s grown size will overpower existing plantings, or if its natural habitat is elsewhere. I found a curious example of this when a few decades later we moved to Mendocino. In the patch of native forest on our property I found two trees with silvery needles. A naturalist friend identified them as some kind of spruce, definitely not native. She told me the story of how they most likely got there. The original developer had been hauled into court for illegally logging the property to create a “view development” and was ordered to replant. She speculated that he picked up a job lot of leftover Christmas trees to fulfill this requirement. Our two spruces, crowded out by redwood and Douglas fir, did not survive much longer.

So what to do about a Christmas tree? Over the years we’ve tried various approaches. We’ve gone to cut-your-own tree farms. But sawing into a young tree felt like committing murder. We’ve bought a cut tree from a lot and kept it outside in a tub of water for as long as possible. Even so, it would be shedding needles even before it came into the house. It would have been been cut weeks before, and shipped hundreds of miles from where it was grown. We’ve thinned out young firs from our own property. But they’ve been spindly little things, too likely to topple.

For the past couple of years, we’ve not bothered with a tree at all. I’ll maybe clip some low-hanging conifer branches to make a big arrangement in a bowl on the dresser or a wreath for the door. But that’s about it. I like my trees living. Like this baby Grand Fir that workers clearing a drainage channel a few weeks ago rescued from an overgrown coyote bush and saved for me.

Sitting down with lions

In many cultures, humans see themselves as siblings to other living beings. In Aotearoa New Zealand, where I grew up, the Māori people recognize landforms such as mountains and rivers as their relatives. Even in Western Judeo-Christian societies, where humans are believed to have been make in God’s likeness and to have dominion over all creatures (Genesis 1:26), people with beloved domestic pets may discover that their relationship is closer to that of peers than of master and subject.

My own views, which come closer to those of scientific pantheism, had a formative moment one summer day in the early 1970s, when my friend Judi and I took our children to the Oakland Zoo. I tell about it in a letter to my parents:

A lion cub recently born at the Denver Zoo. Image from the Denver Post.

The biggest thrill of the day, I got to cuddle a lion cub. Little 7 week-old roly-polies, they had been separated from their mother – I gather the father was threatening to harm them in the cramped quarters of the adult lions. We happened to be there at bottle time, and the keepers brought them out to a low platform in the children’s zoo. They obviously need lots of affection. I was sitting on the platform, and one of them just crawled into my lap, like a kitten or a puppy.

I will remember always the roughness of the cub’s fur under my hand, the warmth of his tiny body, the loudness of his purr, the overwhelming sense of awe that this wild creature trusted me. Here’s a poem about the incident:

The Lion Cub

In the dusty heat of the zoo

a lion roars.

I conjure a dream of Africa

an endless veldt

an alien majesty

concealed in yellow grass.

At the petting zoo

three lion cubs

explore a patch of dirt.

I sit.

One crawls into my lap

nuzzles my hand.

Under thick baby fur

muscles ripple, relax

curl up for a nap.

Wide-eyed, the children watch

and touch.

Distance evaporates.

We are earth family

connected deep in time

in mother love.

How we came to live in Mendocino

We’d never been camping before as a family when, in the summer of 1971, Tony and I decided to take our children, then eight and five, on a short trip to explore some of the northern part of California. On our return, I wrote an ecstatic letter to my parents:

The beach at Russian Gulch State Park, looking under the bridge to the sea. Image by David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons.

25 August 1971

I guess I haven’t told you about our camping trip. We had a marvellous time, and are really sold on camping. We hired a 9×9 tent, and bought a pup tent for the boys, a propane stove and lantern, and a very nice ice box, so we were pretty well set up, and the state park campgrounds are really very civilised, with your own picnic table and food cupboard, and running water, bathrooms and showers not too far way. We spent five nights at Russian Gulch, which is on the Mendocino coast, about 200 miles north of here. This really is a delightful spot. The sea coast here is very rugged, with steep cliffs and caves and tumbled rocks, and grassy meadows on the headlands, with pine and redwood forests behind. The gulch is made by a lush little creek that flows into a tiny cove, making a perfect beach for the children, and the campsites are straggled along the edge of the creek, sheltered from the sea wind, and with a view of redwoods high above you. The weather was beautiful – only a trace of fog a few mornings, and it can be thick all the time. The children got very used to going for long walks, and we also spent a lot of time just sitting and unwinding and watching the wildlife – lots of jays, rabbits, chipmunks and garter snakes. The anchovies were running in the cove, so thick they were being hauled in by waders with nets, and of course they attracted the bigger fish. We were sitting on the beach one afternoon when a group of scuba divers came along with a huge catch, and offered us some, so we had fresh cod for supper.

After describing our impressions of Mendocino village – “splendid weather-beaten old buildings, many of them fine examples of carpenter Gothic, very similar to New Zealand colonial period architecture” – the letter continues:

From Russian Gulch we went on up the coast highway then inland to the Humboldt Redwoods. These are very lovely and impressive, but I think our hearts were still at Russian Gulch.

Here’s where the story takes a mythic turn. Here’s how I tell it now:

Once upon a summer afternoon a man and a woman sat on a beach. As the couple sat and gazed, a young man emerged from the sea. He was beautiful, with golden hair that hung to his shoulders and a body that had known good exercise. From each of his hands hung a fish, whose scales shone wet and silvery.

The woman called out, “Nice catch!” to the fisherman as he passed.

He paused. “Would you like one?”

The woman’s fingers flew to her blushing face. “Oh no, no, I didn’t mean …”

The fisherman lingered. “Please. I have more than I need.” He held out one of the fish.

The man sitting with the woman rose slowly to his feet. The fisherman placed the fish in his out-stretched hands. The man bowed his head and murmured his thanks. That evening, the man and the woman cooked the fish over their campfire and ate its sweet flesh.

After the man and woman returned to the city, every now and then they would feel a tug, as if they were being played on an invisible line. They would say to each other, “We need to go back to that place.” So they would rent a house on the coast for a week or two. The sea sang to them, and each evening a golden light would seep like an enchantment across the drowsy headlands. When their time was up, they would return sadly to the city.

In this way thirty years passed. Each year the tugs grew stronger, the city more and more unbearable. At last they could resist no longer. They left the city. In a house close to where they had eaten the fish, where the scent of the sea came to them, they quietly lived out their days.

Gifts of an old tree

Ripe apricots on a tree. Image from Nature & Garden.

The Cupertino CA neighborhood where I lived in the early 1970s was developed about 1962 on the site of an old apricot orchard, the trees probably planted before the post-WWII boom of the 1950s transformed the orchard-covered Santa Clara Valley into Silicon Valley. The developers had left an apricot tree on each lot. Gnarled and picturesque, they provided welcome shade on hot summer days, and a harvest of apricots for those who loved them. Letters to my parents from two different years offer a glimpse of harvest time:

26 June, 1970

… Meanwhile, the apricots are getting ripe. We have started picking, and they are delicious. Several neighbours with trees (this used to be an orchard) don’t like them too much, so those of us that do are planning to get together and pick for drying. You have to have 65 lbs. of fresh fruit to fill a tray, and a local orchard will sulphur and dry them for us for $30 a tray – pretty cheap dried apricots!

Apricots drying in the sun at the Curry family orchard in San Jose, date unknown. Standing are Douglas and Howard Curry. Image from Lisa Prince Newman’s blog, For the Love of Apricots.

I still remember the fun we had at that orchard in Los Altos Hills. It had a long, open-sided shed with a work table running down the center. My friend Judi and I and other women of the neighborhood stood at the table, cutting or breaking open pound after pound of golden, honey-scented fruit and laying them on the drying trays. Beyond the shed we could see a stretch of bare earth where the big wooden trays of fruit lay open to the sun. About ten days later we returned and were presented with our now-dried fruit, shriveled, somewhat brown, but delicious. A year later:

26 July, 1971

I have also been busy coping with the apricot crop. Our poor old tree has really taken a beating this year. We lost a third of it in the spring with fire blight, and then came home one afternoon when they were just about ripe to find a huge branch crashed to the ground. The poor thing is just dying of old age, and we shouldn’t have let it carry so much fruit. I managed to salvage about 70 lbs. from the broken branch, which we took to a commercial orchard to be dried. They turned out very well this year. They shrink, of course, to a fifth of their weight, but 13 lbs. of dried apricots is a fair quantity. I have also bottled quite a lot, and made jam, and then we had a bright notion of drying another 30 lbs. at home and making wine with them. This is Tony’s project, and he has been having a great time with it. We came home the other night (after eating out with friends) to find that the yeast was working so well in one jar that it had blown the top off, and there was gicky apricot pulp all over the counter!

Decades later, when we finally opened a forgotten bottle of that wine, it was vinegar. Oh well … By then we were no longer living in Cupertino, so I don’t know how much longer that kind old tree lived. I hope its new humans gave it a dignified end.

The way we see ourselves (and others)

Some years ago, when I was still in the workforce, I was rebuked at a performance evaluation for “not putting [myself] forward enough.” Startled, I explained to my boss that in the New Zealand culture in which I grew up, to boast about one’s accomplishments was considered very bad form. Modesty, on the other hand, was praiseworthy. I still think this is true. But I’ve come to realize that New Zealanders had, and probably still have, a contradictory notion: a self-perception of being more self-reliant, more able to come up with creative solutions to problems than people of other nations, such as Americans. This trait, we told ourselves, arose from necessity. Lacking an industrial base, and being so far away from industrial centers, New Zealanders had to import manufactured goods at high cost or make do and mend what we had. Everyone I knew grew their own vegetables. Women sewed and knitted. Car owners kept their vehicles for as long as possible. Frugality was a virtue.

I saw evidence of this sense of superiority to Americans in an exchange of letters with my mother in the early 1970s. I told my parents about a landscaping project Tony and I were working on at the house we’d recently purchased:

April 12, 1971

We turned bricklayers this weekend, and have now laid half of the front courtyard in red brick, basket weave pattern. It is looking beautiful—we are really very proud of ourselves, and it wasn’t as difficult as we expected. We used a dry mortar method, laying a base of sand mixed with cement, and tamping in a richer cement/sand mixture between the bricks. The most tedious part was washing off each brick and smoothing the mortar with a fine spray of water. Then twelve hours later you just slosh the lot down really thoroughly and leave it to set. Needless to say, we are both very fit these days. Apart from a patch of sunburn on my shoulders, I am feeling no ill effects at all today.

In her next letter, Mum must have made some comment on how impressive we must appear to our neighbors, doing all this work ourselves. And how typical of New Zealanders. I responded:

May 2, 1971

New Zealanders don’t have the monopoly on do-it-yourself, you know! You should see the crowds at the handyman-type shops every weekend here.

I continued with an anecdote that shed a less than favorable light on the prejudices of some other Kiwi immigrants:

We were a little amused at another N.Z. couple we know, who have this thing about N.Z. characteristics. We had invited them to dinner, & I tried to give [our friend] directions—after all, Cupertino’s house numbering system is completely random, & I thought they might at least want to know what freeway exit to take. But she pooh-poohed the whole thing—it was “terribly American” to give directions—if they couldn’t find their way by map they weren’t self-respecting N.Zers! As it turned out, they had (inefficiently) double-booked on engagements, & couldn’t come …

Reading this exchange again after so many years, I recognize the beginnings of a shift in allegiance. I was no longer blindly loyal to the sometimes insular attitudes of my birth country. I was learning to question assumptions and beliefs about any group of people. I was learning that being an immigrant is complicated.

The Easter Bunny mystery

How could my husband and I be so mean as to deny our kids the Easter Bunny? I frowned as I reread the letter to my parents stashed in my old black filing cabinet.

12 April 1971

The kids are back at school today after their week of Easter vacation. The weather has been so beautiful and spring-like. This is something I couldn’t really understand until I came to the northern hemisphere—the significance of Easter as a spring festival—the death and rebirth of the god that is an important part of almost every religion there has ever been. Here a big thing at Easter is the Easter Bunny, who is alleged to bring baskets of candy eggs and goodies to kids on Sunday morning. This Tony and I just can’t go along with—somewhat to the kids’ disappointment, I think, though we do buy them a fancy Easter egg, and of course we have the fun and mess of dyeing hard-boiled eggs and hiding them in the garden for an egg hunt. I did allow Simon to share our pet rabbit at school one morning. Bun-Bun was less than enthusiastic about the whole project, but the children were ecstatic.

Part of the reason for our rejection of the Easter Bunny was that Tony and I grew up in New Zealand, where rabbits were despised as pests. Brought by early settlers to a place with no natural predators, their population quickly reached plague proportions, causing major erosion problems. We did have Easter eggs, but given that we celebrated the festival in the Southern Hemisphere autumn, they had no significance other than as a source of sugar and chocolate. Even living in California, we couldn’t see any connection between rabbits and the Christian celebration of the Resurrection. I decided this week to look into the question. I quickly found myself down a fascinating rabbit hole of customs, beliefs, and theories, many of them contradictory.

How the Easter Bunny came to the U.S. seems pretty clear. According to several sources, the creature first arrived in America in the 1700s with German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania and transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws” who brought colored eggs to good children at Easter. As the custom spread across the U.S. the hare somehow transformed itself into the more familiar rabbit and its Easter morning deliveries expanded to include chocolate and other types of candy and gifts.

The hare’s (or rabbit’s) connection with Christianity are more complicated. For the first few centuries, the Christian festival coincided with the Jewish Passover, which is when the historical events surrounding Jesus’s death occurred. Though the Christian calendar has since been modified, both festivals are still close to each other in spring. Both are based on a lunar calendar; the date of Easter was defined in 325 CE by the Council of Nicaea as the first Sunday after the first Full Moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox. In Anglo-Saxon regions of Northern Europe, the Christian festival seems to have merged with a pre-existing equinox festival honoring Eostre, the goddess of spring, and Christians continued to use the name of the goddess to designate the season. Since hares and rabbits give birth to large litters in early spring, they have long been recognized as symbols of the rising fertility of the earth at the vernal equinox.

No, no, no, say some Catholic writers. The Easter Bunny has Christian origins. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that the hare could conceive again while pregnant, thus shortening the time between litters and delivering more offspring during a breeding season. Later Greek writers such as Pliny and Plutarch expounded the notion that hares (and rabbits, by association) were hermaphrodite, and thus could self-impregnate and reproduce as virgins. During the medieval period, hares and rabbits began appearing in illuminated manuscripts and paintings depicting the Virgin Mary, serving as an allegorical illustration of her virginity.

Two pregnancies at once? Intrigued, I veer into another passageway of my research rabbit warren. It turns out that, as the Smithsonian Magazine put it, “Aristotle got it right: the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) can get pregnant while it’s pregnant.” In 2010, scientists of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, Germany, led by Dr. Kathleen Roellig, published the results of their study. Using selective breeding and high-resolution ultrasonography, they showed that a male hare can fertilize a female during late pregnancy. The resulting embryos will develop around four days before delivery of the first pregnancy. To quote from the Smithsonian article: “The embryos don’t have any place to go at that time, however, since the uterus is occupied by the embryos’ older brothers and sisters. So the embryos hang out in the oviduct, rather like when you wait in your car for a parking space to open up. Once the uterus is free, the embryos move in.”

My head is spinning. I think I need chocolate.

A legacy of crocheted lace

A comment in an old letter to my mother catches my eye:

March 1, 1971

I can’t remember anything about that bit of crochet, Mum, but I guess it probably is mine. Now it will sit in my workbox for years!

Do I still have it? I open the Cadbury’s Chocolate box that holds my collection of crochet hooks and sundry balls of crochet thread. On top sits a small piece of lace, obviously the beginnings of an ambitious project. Was it the piece that cluttered Mum’s workbox? Probably.

The art of crochet was honored in my mother’s family, passed on, like all domestic arts, from generation to generation. The most noted expert was my great-grandmother, Sarah Jane Caundle, whom I met a few times when I was a child. She was born in 1864 to Irish immigrants on a New Zealand goldfield. In a reminiscence my mother wrote:

Outside the back door [of Grandma’s house] in the sun was a stool to sit on. Across the yard in a shed that housed the wash house with its copper and wooden tubs with the toilet next to it. Grandma washed the clothes in the old way with a well-stoked fire under the copper to boil the sheets, etc. The tubs for the rinsing and blueing with a hand-turned wringer between them. While visiting as a small girl I was being taught how to crochet. Trying to make my doll a pink woolen petticoat like the ones Grandma made for us. Something would not go right so I called for assistance. There was Grandma coming across the yard at her usual jog-trot wiping the soapsuds off her arms on her apron (Must always wear an apron) to sort out my muddle. The picture is still so clear in my mind.

… As we grew older we were given doilies and crochet-edged linen for our “box.” At each 21st birthday each granddaughter was presented with an afternoon tea cloth with a wide edge of crochet lace.

Before she died in 1951, Great-Grandma Caundle had started making doilies for her great-granddaughters. I missed out, but inherited a piece of her work from my mother. Fascinated by Mum’s stories about her grandmother’s life, I put together a poem:

Great-Grandma’s Doily

Early afternoon, when chores were done,

Great-Grandma put her feet up on the kitchen couch

and gave herself an hour with crochet hook and thread

to figure out the sequence from a photograph—

chain and double loop and treble—

the mathematical progression of the rounds

revealing patterns satisfying in their laciness.

She learned the art at her mother’s knee

in the dirt-floored hut at the Puriri claim.

Her mother learned it from her Mam

back in Ireland before famine memories

and rumors of gold in the far-off colonies

took Bernie Donnelly and his new young wife

adventuring across the world.

There was a dame school at the diggings.

Great-Grandma might have gone some days

but not enough for fluency in letters.

She had sisters and brothers to mind,

manuka-twig brooms to fashion for the floor,

clay to fetch for the hearth’s weekly whitewash of mud.

She entered service as a housemaid at eleven.

Later came marriage and children of her own,

nine of them, then grandchildren to care for.

All this time persisting in her art,

gifting to daughters and grand-daughters

lacy linens for their marriage chests.

I have one doily, handed down, an oval of white linen

edged with a crocheted frill of tulips in a row,

each stitch pulled neat and tight, a testament

to discipline and practice, and the will

to make time for her art.

A spat in slow motion

A spat between parent and adult child is different when conducted on flimsy blue international air letter forms. For one thing, it happens in slow motion: weeks pass between riposte and retort. For another, it’s solitary: neither side can see the angry tears of the other. And it’s documented; that is, if letters are kept. My mother kept all mine, and gave the bundle back to me. I constantly regret that I didn’t keep hers, so have to guess at the comment to which a letter of hers or mine would have responded.

A typical example happened in late 1971. Decades later, as I read through my old words, I recognize patterns of individuation familiar to every psychoanalyst.

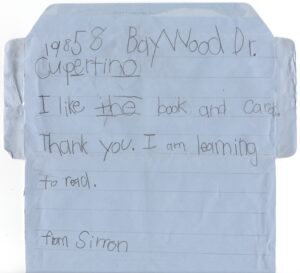

It started with a postscript to a birthday thank-you note my six-year-old son had written on Nov. 13, 1971.

At the bottom of the page I’d scrawled:

Do I assume that you have given up writing to me?

Mum’s response, as I remember it, was to the effect that if she wrote to one member of my family, it was to be assumed that she was thinking of us all. Here’s my response:

Nov. 23, 1971

I’m sorry that you got so uptight about my comment, Mum. However, I think we should clear up some basic misunderstandings about the children. I am delighted that you have written to them, and they are too. They think it is pretty special when an adult relative takes an interest in them. But it is very important to me that the kids be seen as individual people, with interests and responsibilities of their own, and this includes developing communications with other adults outside the immediate family. This, I think, is a reaction to my own childhood, when you tended to take over any attempts we made to establish relationships with other people. Now don’t get upset – I’m just trying to show you how I see myself, and how I see my kids. If you only have time to write to the kids, that’s O.K. I’ll encourage them to answer your letters, but there may be some long gaps. They are not big enough yet to handle a regular correspondence. But I have no intention of taking over the responsibility for them, nor of regarding your letters to them as some sort of gimmick substitute. I am an individual person too, and I haven’t had a letter from you since August.

We made up our differences in the next round of letters. In response to her plaint about the difficulty of being a parent, I wrote:

Dec. 14, 1971

I know what you mean, Mum, about bringing up kids. I sometimes wonder what these two will hold against me when they grow up, and it’s sure to be something I’ve never thought of.

Saga of an unpublished novel

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a beat-up cardboard box that contains the dog-eared manuscript of my first completed novel in the US, “A Stone from the Wall.” The saga of my attempts to get it published, as reflected in letters to my parents, may get a nod of recognition from other aspiring writers.

March 15, 1972

I have finally got my book off my hands. I received an invitation last week to submit it to Houghton Mifflin Co., one of the most prestigious of the major publishing companies, so after a final frantic effort to finish typing the fair copy, it is now on its way. Whether they will buy it or not is of course another matter, but just to get an editor there enthusiastic about the idea is a tremendous boost. It is their sort of book—a serious look at a contemporary theme. My subject is racial prejudice, and the point I am trying to make is that, for a white person trying to come to terms with racial problems, the most difficult, and even painful, part is learning to recognize your own prejudices. This is mainly, of course, because the more concerned you become, the more you want to think of yourself as one of the good guys.

July 2, 1972

I was going to leave finishing this until after the mailman came today, but don’t really see the point. If I seem a bit edgy in this letter, I am. I was told by Random House that I would hear from them within 4-6 weeks. It is now nearly 5 weeks, and my heart starts hurting every time the mail truck goes up the road. It’s very tedious bracing yourself for rejection every day.

At some point I received a hand-written rejection note from the editor-in-chief of an eminent house—I believe it was Robert Gottlieb of Alfred A. Knopf—who complimented me on my “ability to make my characters come alive,” which buoyed me up for a few more rounds of submission and rejection. I no longer have the note or, for that matter, any of the many rejection notices I received.

July 25, 1972

My book showed up on the doorstep again, as expected. Disappointing of course, but this time I have decided to revise a lot of it before sending it out again. When you are writing fiction, you become in a very real sense the characters you are writing about, and sometimes it is difficult to stand back and look at them objectively—like it is difficult to look at yourself. But now I think I can see at least some areas where the characters are not interesting, or even not alive, but just vehicles for ideas. However, I am going to leave it now until fall—it’s just too difficult to work over the summer. The kids are very good, but they are something of a distraction. In the meantime I have various other articles and poems doing the rounds. They come back periodically, of course, but I figure that with enough things going, I’ll get somewhere eventually. I have had a couple of commissions from Tui [my editor at the Christchurch Press] which I have now sent off … I do still get very depressed every so often, but Tony usually manages to pull me out of it if I can’t shake it off myself. I even made a list this week of all the other things I was going to accomplish this summer. Boring jobs like cleaning the oven figure rather prominently …

November 1972

I am trying to get back to my novel, but keep getting sidetracked with new ideas [for stories and articles]. Have just finished grading a big set of students’ short stories for Millicent [the high school teacher for whom I worked]. Tremendous ideas and effort, but my main reaction as I tore each one apart was, my gosh, that’s what’s wrong with my writing too.

Discouraged, and preoccupied with other projects, I eventually gave up and moved on. As I noted in my blog essay “The Other Side of the Freeway,” I understand now why “A Stone from the Wall” never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject. I didn’t understand how much the life experiences, interests, and even musical tastes of my African-American characters might be different from those of my white characters. Though I devoured my subscription to The Writer magazine from cover to cover, the protocols of book publishing still felt like an enormous black hole. The battered manuscript box deservedly stays in the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet.

The other side of the freeway

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a battered cardboard box containing the manuscript of a novel I wrote in the early 1970s. I understand now why it never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject: racial discrimination in housing. As I reread some of the text, I recalled the shock I felt when I first grasped the magnitude of the social gaps. The descriptions that follow come from my own experience as I researched the book, and it began my involvement with the fair housing movement.

Here is the central character Karen, a newspaper reporter, visiting the black ghetto of East Palo Alto for the first time to interview the director of a community advice center:

She knew vaguely that East Palo Alto belonged to the county. … She crossed the county line now, and accelerated to get onto the overpass that spanned the freeway. As she came down the ramp on the other side, she knew she was in a different country. The road was suddenly pot-holed and bumpy, and brown dust rose in thick choking swirls from its verges. She slowed, and looked about her. Such tiny bedraggled houses, desperately in need of paint. Yards littered with junk, yet here and there a brave attempt at order and color, a flower-bed, a well-cut lawn. She came upon a few tatty shops. Surely this couldn’t be the main shopping center? Yet soon she could see the sign, NAIROBI SHOPPING CENTER, and underneath, in a language she could not understand, UHURU NA UMOJA.

She had to force herself to open the door. Lurid accounts of rapes and muggings and violence in the streets flooded her mind. Here she was the enemy. She wanted to jump back into the car and get out, away from this place.

A woman passed, with two small children, headed for the market. She looked indifferently at Karen as she passed, then turned to scold one of the children, who was whining for candy. Karen let out the breath she had been involuntarily holding, and made herself move on. … Across the road, outside a liquor store, a black knot of middle-aged men stood transfixed in time, waiting for nothing.

It was hot. The dust lifted lazily as she walked. Something about the huge trees, and the stillness of the air, brought to her mind descriptions she had read of towns in the southern states. But this was California. It did not make sense. A mockingbird flashed its wings across her path, still proudly singing.

Karen does her interview, in which she learns about the pressures of living in East Palo Alto (and also finds herself attracted to Paul, the advice center director).

She said goodbye, and walked slowly back to the car, past the Louisiana Soul Food Kitchen and the Black and Tan Barber. The heat and dust were almost unbearable.

Back across the freeway, she noticed for the first time the neatly swinging redwood sign: Welcome to Palo Alto. A few blocks further down University Avenue and it hit her like a punch in the gut. She pulled over to the side of the road and rested her head on the steering wheel, fighting back an impulse to vomit. The contrast was an obscenity. Huge magnolias here lined the street on both sides, giving deep dappled shade to the well-paved highway. Between the road and the white concrete sidewalks rose great greening mounds of juniper and ivy, and beyond them, with manicured lawns and discreet sprinkler systems, were the complacent mansions of the rich.