Archive for the ‘domesticity’ Category

Rumblings in the socialist paradise

I sold this early 1970s article about feminism in New Zealand to a US magazine. Unfortunately, the journal folded just after I’d received the galley proofs. Disappointing, but hey, these things happen. Reading the galleys again, I recognize many of my own frustrations, and understand a little better why I had to leave. I realize, of course, that New Zealand society today is very different from what it was then.

Letter From New Zealand

In New Zealand we say it is the land that shapes the people.

The land is lovely, but aloof; it has not welcomed intruders. For a few square miles the forest and scrub have given way, but the houses sit impermanent as boxes on the clearings, and in the towns the raw suburbs perch in self-conscious rows.

Europeans have been here for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain they brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. Together these two strands wove a welfare state that, in providing an economic floor beneath which no family can fall, has codified the disparities between the sexes, and underlined the definition of woman as housewife.

In the 1930s and ‘40s the pattern of social experiment these pioneers began reached its flowering in a social security system that offered a minimum wage, compulsory arbitration of wage disputes, pensions for invalids and deserted wives, family allowances that can be capitalized into housing down payments, low interest housing loans, low rent state houses, and a national health service that provides free medicines and medical treatment. A school dental service provides free dental care for all children. Most recently, in April 1974, an accident compensation scheme went into effect that covers everyone on New Zealand soil, whether earning money or not.

It is a complacently comfortable floor. But at its foundation is the assumption that the only proper place for a woman is in the home taking care of the children.

The welfare of the child is the prevailing argument. Says Norman King, New Zealand Minister of Social Welfare: “The majority feel that a close relationship with its own mother is the birthright of the New Zealand child. We do not want to encourage the adoption of a lifestyle in New Zealand where it becomes normal for the care of very young children to be a specialist task carried out by trained staff in group situations away from the family.”

New Zealand women achieved the right to vote in 1893, second only to Wyoming. Otago University in N.Z. admitted women to degree courses in 1871, the first in the British Empire. There are today very few women Members of Parliament, and no women at all in the administrative levels of higher education. Those who have reached positions of authority in any field are regarded as exceptions to the norm. And in a country as small as New Zealand, to be different is to be disapproved. A friend who returned home after ten years in London says: “Everything in New Zealand presses on me to settle down, to conform, to live safely, not to take risks.” My elder sister, Evelyn Stokes, has a doctorate in geography from an American university. Hostile vibrations still echo in our family over her decision to place her two children in a day care nursery so she could continue her university teaching.

Official thinking assumes that a mother who goes out to work does so either from economic necessity or from disproportionate greed. The idea that women might have talents other than domestic comes hard to New Zealanders. It is certainly not fostered by our education system, which from the start locks children into rigid sex role definitions.

From six-year-old Donald, Evelyn Stokes’s son, comes a crumpled school paper.

Check what toys girls like, he is instructed.

Big and little dolls? Yes, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A train? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A football? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

At the high school level the curriculum encourages vocational discrimination by sex: academic girls are steered towards the arts rather than the sciences, and average girls towards secretarial or home-craft courses.

But the winds of rebellion, fanned by global news services and travelers’ tales, are stirring the curtains at the kitchen windows. Women are staying at school longer and leaving with higher educational qualifications than ten years ago. The percentages of women and of married women in the work force are still lower than most western countries. But their numbers are increasing steadily, despite recent changes in the family benefit structure aimed at dissuading mothers from going out to work. Equal pay recently became law, and will be at least nominally applicable to all areas of the workforce by 1978.

Social custom compounds the problems of those married women who do go out to work.

Pat Brown has her own advertising agency. She told me that a company party with her husband, chief chemist at a freezing works, she attempted to discuss with his colleagues the implications of advertising and the sale of meat. Her husband’s boss took her firmly by the hand and led her to the far side of the room, where the other wives were discussing babies and knitting patterns. “This is your place,” he said.

Domestic duties are another stumbling block. Marriage counselor Marianne Thorpe says: “The difficulty is that women feel that they are responsible for the care of the home and children (and they get almost no help in this task), and this makes working outside the home a complicated business.” Evelyn Stokes and her husband Brian, head of math at a teachers’ college, share responsibility for housework and child care. It is an unusual set-up for a New Zealand family. More typical is Ray Lealand, now retired after a double career of clerical work and home-making, who says: “The most difficult problem I faced whilst working was non-cooperation from my husband.”

Role demarcation in some families is incredibly rigid. One friend recalls the raised eyebrows in her family when as a young bride she took on the vegetable garden. “That’s the husband’s job,” she was told. “The wife does the flowers.”

Since most women expect to stay home once they have a child, the idea of maternity leave is not widely accepted. When Evelyn Stokes applied for leave for the birth of her second child, the committee set up to look into the matter came back with a regulation that a mother who applies for maternity leave “is required to satisfy the university that her additional family duties are compatible with the continuation of her employment.”

Child care facilities for working mothers are inadequate, and though support for day care centers was a major plank in the ruling Labour Party’s 1972 election platform, its implementation has been whittled down to a subsidy to needy children in existing voluntary centers. Part-time employment coinciding with school hours is widely accepted, but employers will take on mothers of preschoolers only as a last resort, and use the argument of family responsibilities to pin women to the lower scale, “temporary” job classifications.

Sex role definitions still apply in employment. Six occupation groups employ 65% of New Zealand’s working women: clerical, sales, clothing manufacture, teaching, nursing, and domestic service. But there has been some movement into the traditionally male areas of drafting, electronics, and electrical work, and into the newer technological jobs like computer programming or systems analysis, where sex-exclusive traditions have not yet calcified. With a shortage of male labor in many fields, a few pioneers are braving the public ridicule and breaking down job opportunity barriers. One such incident, in 1972, even rated media coverage. Two girls applied for jobs in an Auckland factory as aluminum glaziers, only to be told this was not a woman’s job. When they asked “Why not?’ no answer could be found, and they were taken on.

This thread of social change is closely woven with another that is a constant in New Zealand life. Few in numbers, and isolated by thousands of miles from the sources of our culture, we have been almost pathologically dependent on the word from the outside world. I remember my first beat as a cub reporter; I scurried round the tourist hotels of Christchurch, winkling out startled visitors and begging them to express an opinion. Any opinion. Still the pattern continues. Articulate voices from abroad, no matter what their status, receive far more attention than local expects on the same subject.

The feminist movement is a case in point. Local groups springing up in the past few years have found a climate of hostility and ridicule. The ideas of American feminists, distorted by distance and by different cultural norms, have seemed to many to be irrelevant to the New Zealand experience. Then early in 1973 two visitors coincided: Evelyn Reed, an American Marxist feminist who advocated abortion law reform and improved child care facilities, and Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist know for his work on the deleterious effects of maternal deprivation on a child’s mental health. Both, basking in the aura of the magic words “from overseas,” were taken seriously by the local press. Margot Roth, editor of the Journal of the N.Z. Society for Research on Women, comments that the resulting controversy opened up a much wider range than usual of questions concerning women, and helped lay the foundation for the success of a United Women’s Convention held September 1973 in Auckland to mark the 80th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

The purpose of the convention, according to the organizers, was to correct the distorted view New Zealand women had of modern feminism, to raise the status and self-confidence of women, and to increase the numbers of women willing to work on behalf of women’s issues.

Statistics indicate that the fifteen hundred women who attended, while better educated and more likely to be employed than the average, nevertheless made up a remarkably accurate cross-section of New Zealand society. The issues discussed were those that concern women everywhere: job opportunities, control of their bodies, marriage and child care, sex stereotyping.

Press reportage of the Convention again sought to trivialize and ridicule. Afternoon TV revealed to local mums some of the hogwash poured down the verbal ducts at the United Women’s Convention, reported one city daily.

However, rage over press flippancy reinforced a feeling of unity at the conference, and the consensus of those who attended is that, for the first time, women from the whole range of backgrounds and interests in New Zealand life experienced a feeling of sisterhood.

The floodgates are open. Women with common interests are pooling resources. The prestigious National Council of Women, umbrella for all women’s organizations in New Zealand, and for long a stronghold of the traditional view, is now espousing the cause of equality and encouraging its affiliated groups to contribute.

It is hard to say what the future will hold. Though New Zealanders travel the world as casually as migrating godwits, jet planes cannot eliminate the sense of lonely isolation that makes us belittle our homegrown prophets. The land still broods, raw, stubborn, and the people it has bred still revere the sheep shearer above the artist. On embroidered tablecloths, housewives still set teas of cream cakes and scones, and rows of preserves still gleam on pantry shelves.

But the women of New Zealand have a stubborn streak too. Diffident, shy, self-conscious in proclaiming the ideas that come from an almost alien American culture, we are nevertheless gathering strength. The spirit that made New Zealand one of the most comfortable societies in the world may yet take a mattock to the scrublands of tradition, and graze the new fields of equality.

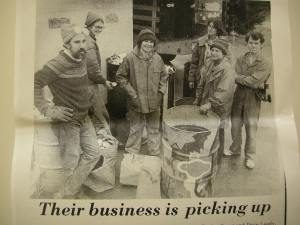

Recycling centers: the old days

Rummaging through my old black filing cabinet, I came across an article I wrote in 1972 about recycling centers that was published in my Christchurch, New Zealand paper. These days, when everything recyclable gets dumped into the Blue Bin and carted away, I though it might be fun to read about the beginnings of the movement.

Rummaging through my old black filing cabinet, I came across an article I wrote in 1972 about recycling centers that was published in my Christchurch, New Zealand paper. These days, when everything recyclable gets dumped into the Blue Bin and carted away, I though it might be fun to read about the beginnings of the movement.

COME ON DOWN TO THE RECYCLING CENTER

Cupertino, CA

Spurred on by their ecology-minded kids, Californian families these days are loading up the station wagon at weekends with squashed cans, bottles, aluminum foil, and old newspapers, and heading for the local recycling depot.

The movement started a few years ago, when beer manufacturers discovered that they could earn bonus points in public relations by buying back and recycling the aluminum beer cans that had become an inevitable part of the landscape of the nation’s beaches and parks. As concern for the environment became a national obsession, clean-up campaigns became a fashionable, and profitable, project for youth groups.

A 1970s recycling center. Image from Bainbridge Island, WA Community Cafe

Then the kids started taking over the collection depots. Each summer, high school social studies departments set up their own recycling centers. Sometimes the logistics of getting students organized can be overwhelming. One summer the boxes and bottles piled up embarrassingly high in the parking lot of a local supermarket before the kids from the high school across the road got themselves coordinated. And last year student apathy on the prestigious Stanford University campus allowed the recyclable trash to spread like a slum over the elegant grounds.

But a well-run recycling center can be a pleasure to visit. A Los Altos youth group set up shop in the grounds of an abandoned school. Every weekend enthusiastic volunteers were there, sorting, packing, stacking. Cheerful hand-lettered signs directed customers to the right cardboard carton for each item, and warned about the broken glass on the ground. One member invented an ingenious wooden lever for pressing the cans as flat as can be, and this is always in use, though most families now bring the stuff in already sorted and squashed. “Doing your bit for ecology’ has become an acceptable chore for children, and there is a therapeutic value in bashing cans nearly comparable to chopping firewood, back in the good old days before central heating and all-electric kitchens.

Some local government projects have fared less well. Neighboring Sunnyvale’s municipal recycling center is a lonely outpost in the corner of the city dump, way down in the swamp beyond the aerospace plants and the defense installations. Not surprisingly, the center made a loss last year.

Cupertino has tried to get the best of both worlds. The local chapter of Jaycees, supported by the city, the college administration, and the students’ Ecology Corps, has set up a recycling depot in a corner of the beautiful, and central, De Anza College grounds. It is less chaotic than the Los Altos center: a neat redwood fence surrounds the area, and the materials are contained in big steel skips. But there is still the sense of community involvement, the cheerful bustle on a Saturday morning, the satisfying clunk of bottles smashing into the skips. First quarter earnings showed a modest profit. The glass and aluminum are bought back by their respective manufacturers, and the tin and bi-metal go to a local producer of nursery pots.

Some recycling centers take newspaper, which is now reused for a variety of items, from dinner napkins to stationery. But the youth club paper drive, long a part of American life, takes care of most of this, and the big brown newspaper skip on the local school grounds is a familiar part of the landscape.

What about the future? Development suggestions have included a return to the regular garbage collection, with automatic sorters at the dumps to pick up reusable materials. The idea sounds more efficient, more appropriate to industrial America. But somehow it doesn’t quite fit the new environmental consciousness, with its emphasis on individual effort. And it won’t be nearly so much fun.

The nesting instinct

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

Feb. 2, 1970

… I cleaned the apartment, then of course rushed back here to try to get a bit more cleaning up and unpacking done. The previous owner was a pretty sloppy housekeeper – still, I guess everyone complains about the other woman’s methods. Anyway, most of the house is now more or less presentable …

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Or, as webmd.com puts it: “Just as birds are hardwired to build nests for protecting their young, we humans are primed to create a safe environment for our new offspring.”

I wasn’t pregnant in 1970, so I looked up sites with information on spring cleaning. I found checklists, some tentative discussion of the custom’s origin in ancient traditions and religious practices, as well as practical reasons for the task, especially in places of cold winters and times of sooty wood- and coal-burning heating facilities. And on sites about moving into a house, there were checklist after checklist, all of them assuming that the previous owner/tenant is by definition a germ-carrying slob, and that the new occupant is motivated to clean every inch of the place. A few examples:

From Angie’s List:

- “Previous residents surely cleaned the bathroom, but there is no harm in scrubbing away your own way as this room can be one of the more germ-filled places in the house.”

- “The insides of all cabinets and drawers were most likely ignored by the previous tenants or homeowners.”

- “Dust the top of the doors and disinfect all doorknobs.”

From Bed Bath & Beyond:

- “Your dream home sure looked spotless during the open house. But gird yourself: No matter how clean the place seemed, it’s likely there are some dirty surprises in store for move-in day.”

[This site pays particular attention to chandelier light fixtures, crown moldings, ceiling fans, doors & knobs, refrigerator vent, dishwasher, furnace, ductwork, washer & dryer]

From The Spruce:

- “You should always do a thorough clean before your stuff arrives.”

- “The kitchen is probably the first place to start. Not only because it tends to be where icky sticky things collect, but also because you’ll want to get rid of the former tenant’s cooking smells.”

[Detailed instructions for fridge, stove, cabinets, counters, sink, walls, floors]

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

In celebration of friendship

Browsing through letters from my early years in California, I am struck by how often new names crop up: work colleagues of Tony’s who invited us to their homes, families we met at a playground or children’s event, neighbors. I realize now that my parents often had no idea who I was talking about. It didn’t matter. Having no family nearby, our new friends loomed large in our lives. We did our best to reciprocate, but it never felt like enough. Here are some examples from early 1970, when we were moving from the apartment complex into our new house:

Browsing through letters from my early years in California, I am struck by how often new names crop up: work colleagues of Tony’s who invited us to their homes, families we met at a playground or children’s event, neighbors. I realize now that my parents often had no idea who I was talking about. It didn’t matter. Having no family nearby, our new friends loomed large in our lives. We did our best to reciprocate, but it never felt like enough. Here are some examples from early 1970, when we were moving from the apartment complex into our new house:

Feb. 2, 1970

The chaos is gradually dying down here. We moved in a week ago on Sunday, but don’t think we could have done it without our incredibly good friends. Al & Jim provided manpower & car to help with the furniture, while Judi & Margie not only took care of the kids, but provided meals for everybody all day. And this with Judi pregnant and nauseous, & David running a temp. of 103°. … I have not been too well this week either… Again, Margie came to the rescue, & had David & Simon over there while I cleaned the apartment …

I am having Margie’s kids tomorrow while she takes visiting family to Monterey for the day…

Feb. 15, 1970

Several of my new neighbours gave a coffee morning for me on Friday – very pleasant, though naturally a little stiff & formal – but it is nice to be formally introduced to people. Then this afternoon the husband of one of the women I met came over & made himself known to Tony, which was rather nice. And of course, my old friends from the apartments have been dropping in.

Feb. 28, 1970

Between downpours I have been digging a hole to plant a young live oak that the Gaubatz’s have given us – some bird or squirrel planted it in their yard, but now it has to go to make way for an extension to their house. It is a lovely specimen, so I hope it survives the move. We were up there last weekend also, & Don G. showered us with all sorts of bits for the garden – calendula seedlings, shasta daisies, calla lilies, violets, artichokes, and thornless blackberry. In return we are giving them a pair of podocarpus trees that look very stiff by our front door, and a half-starved rhododendron that someone planted too close to its fellows.

Practically all the people we met in Silicon Valley were immigrants, either from other countries or other states of the US, all of us heady with the intellectual ferment of the new technologies, all of us just another foreigner among the many. What mattered was that we took care of each other, respected our differences, and learned from each other. Some of these friendships have lasted for decades, even through moves to other towns and changes in life situations.

In these troubled times, it feels important to celebrate the values of friendship and caring. Thank you, all my dear friends.

The appeal of the picturesque

I’ve been wondering: what is it about an old house or barn that appeals so much that we describe the scene as “picturesque.” The question came up as I reread a January 1970 letter to my parents describing the purchase of a house in Cupertino, CA. Our new home was a typical early 1960s tract house with scalloped trim and prominent garage. The place was certainly not picturesque, but it was within our price range. I wrote:

It’s a very nice little house – 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, big sitting room with dining area at one end, small family room opening to a neat little kitchen, 2-car garage with laundry facilities in it. Very attractive inside, though not very prepossessing from the outside. However, this is just a matter of landscaping – other houses in the street are just lovely, but the garden of this one is just bare grass.

Looking back on that time, what comes most vividly to mind is another house I saw while house-hunting, a charming old farmhouse dating from the time when the Santa Clara Valley was so full of orchards it was called “The Valley of Heart’s Delight.” As I walked through with the realtor, I paused in what must have been a utility porch and mud room. The unfinished walls of the room were black with mold. The realtor shrugged when I pointed it out. The price was right, but I chose not to make an offer.

There’s a significant difference, of course, between the picturesque, which has been defined as that kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture and a habitable structure for humans. But what is it in the human psyche that is drawn to the antique? Rummaging around on the web, I found quotes such as:

(esp. of a place) attractive in appearance, especially in an old-fashioned way

A picturesque place is attractive and interesting, and has no ugly modern buildings.

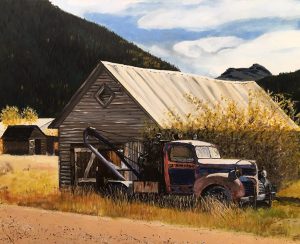

My friend Sandy Peters says it well. Commenting on a Portola Art Gallery exhibition of her husband Jerry Peters’ paintings of old battered trucks in rural settings, she wrote: They demonstrate how the beauty of nature blends seamlessly with the wisdom of age.

However, with age comes death. When we first moved to Mendocino seventeen years ago, a cabin stood among the trees along Highway 128, not far north of Yorkville. Its bare board were gray with age, the sway-backed roof shingles covered with moss. Over the years, the roof has slowly caved in, until now the cabin is a jumbled pile of boards. At first it was picturesque. Now when I drive by, I am sad.

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

Night train in winter

New Zealand’s Volcanic Plateau in daytime. Image from https://www.flyingandtravel.com/skiing-north-island-whakapapa-ruapehu/

An image haunts my mind like an old song in a minor key. From a train window late at night, a desert plateau spreads into the distance. In the foreground, scattered clumps of tussock, stiff with frost, emerge from a dusting of snow. On the horizon, three volcanic cones gleam white against the blackness. The scene is both bleak and beautiful. Tranquil even. A calmness fills me as I remember.

The year was 1968, the place the center of North Island, New Zealand, somewhere north of Ohakune on the Main Trunk Line. I was traveling by train, alone, to a funeral.

It had been a tense few months since my husband and I, with two young children, had decided to make the trip back to New Zealand, our home country, to visit our families. First there was boundary-setting to do with my mother on how much relation-visiting I would allow her to inflict on my shy infants. A few weeks prior to our departure date the children developed chickenpox, one after the other, pushing our schedule further into New Zealand’s winter and upending an itinerary that carefully divided our limited time between my husband’s family and mine. On arrival, I discovered my mother had sabotaged this division by taking a motel room in my mother-in-law’s town. Each day she ensconced herself in mother-in-law’s tiny living-room, dragging my embarrassed father and school-age sister with her. Other sisters later told me they’d remonstrated with her, but she’d insisted she had a right to see her long-gone daughter as soon as I arrived. My mother-in-law was gracious, but I was furious on her behalf.

Then fate intervened. On a night of heavy rain, my maternal grandmother’s husband stepped from between parked cars into the path of an oncoming truck. I did not know my step-grandfather, since he and grandma married about the time I left for college. But grandma had been an important part of my childhood, and she loved this man, so it mattered that I go to the funeral. Leaving the children with their father and his mother, I set out on the overnight journey. First a railcar from New Plymouth, on the west coast, which connected at Marton with the Night Limited express that ran each night between Auckland and Wellington.

I knew this train, having ridden it back and forth many times when I was in college. There was comfort in the familiar sway and smell of the overheated, stuffy carriage, the faded red plush covering high-backed seats, the clackety-clack of the wheels. There was peace too. For the first time since the children were born I was alone, with no responsibilities.

Beyond the desert and mountain vista on the Volcanic Plateau, the chuff and grind of the diesel engine became more labored as the narrow-gauge track rose into a more broken landscape, with forest a dark overhang outside the window. Then Taumarunui Station at 2:00 am, the refreshment stop, where bleary passengers streamed into the tea-room for meat pies or slabs of yellow pound cake and milky tea in thick white china cups. Sometime around dawn, a stop at Te Kuiti where relatives met me for the two-hour drive to Tauranga, where the funeral was to be held. Calmed by the journey, I willingly renewed acquaintance with uncles and cousins and aunts I’d argued with my mother about seeing.

Looking back, I understand what that spare, snow-covered landscape was telling me: that the land is vastly more important than human quarrels, that I needed to let go of my day-to-day tensions and anxieties and become merged with the wholeness of the earth.

The best laid schemes

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley

–Robert Burns

I’ll never forget how furious my mother was with me that day. I was about seven years old, and spending the day at my grandparents’ house while Mum ran last-minute errands. The next morning my parents, sisters and I were to leave on a camping trip, the first real vacation my family had ever had; Dad was an auto mechanic, and summer was his busiest time, with all the beach-goers flocking into our seaside town and needing help with their vehicles.

That afternoon I started to feel poorly. Grandma felt my forehead and promptly tucked me into bed. By the time Mum bustled in to pick me up the cause of my misery was obvious: my body covered with the red blisters of chickenpox.

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

11 May 1968

I did write to you earlier in the week, but it was obsolete before it was even posted, so I tore it up instead. Isn’t this business just typical of kids? Anyway, here is the present state of play: we have bookings … [revised details]… But this flight depends on Simon [our two-year-old] coming out in spots this weekend, or Tuesday at the latest. The chances are higher that we shall postpone again until the following week …

Here is my calculation of the odds: Incubation period 11-21 days. Say David came out in spots on the 11th day, and Simon, from the same contact, on the 21st day (i.e., next Friday) he has two weeks to have it over with.

Say Simon missed David’s contact, and gets it from David, he can come out in spots on the 11th, 12th, or 13th day, and has 11 days, or a reasonable chance, to be free of scabs. (The airline will take him if a doctor will certify that he is not contagious.)

Say Simon decides not to get it at all, he will have passed the 21st day by two days.

The only problem will be if he gets it from David after the 13th day. The 14th day is borderline; after that we would have to cancel. We are in a bit of a quandary as to what to do then … Meanwhile we are all twiddling our thumbs, and willing Simon to produce ‘chickenpops’, as he calls them. It seems such an awful thing to do to such an innocent little poppet, but so far he has remained obstinately clear-skinned and perky…

The ironic thing is that we had a mumps crisis last week. One of the children’s closest friends came down with mumps about two weeks ago. We flapped around for a while, seriously considered gamma globulin, in spite of the cost (about $60 just for shots for myself and the children). We had braced ourselves to go through with it, when at the last minute the doctor just couldn’t get hold of any, so decided to try a new mumps vaccine instead. This is a lifelong immunity, but doesn’t take full effect for a month. By this time, he hoped that the vaccine would have built up enough antibodies to resist the disease. So far it is working. It is quite interesting being guinea-pigs, and considerably less expensive, at only $5 each. So instead we get the chickenpox!

…I have just come in from a walk – after four days in the house with kids, I needed it, but have come back feeling more depressed than ever about the whole business.

Monday – Have postponed until 31 May…

20 May 1968

Believe it or not, Simon actually produced some ‘chickenpops’ today, so we have started believing again that we are really coming. … I’m still not really convinced that we will arrive, but as we are going in this Wednesday to pick up the tickets, I had better stir myself out of this legarthy.

The irony of this story is that when we finally arrived at Nandi, Fiji on our way to New Zealand, the immigration officer noticed that David’s smallpox vaccination was outdated. (You needed this at that time to get into New Zealand). In our panic over chickenpox, we has totally spaced on this detail. Fortunately the officer was kind “Just get it done as soon as you get there,” he said as he stamped our papers.

Uncles & cousins & aunts, oh my!

Recently, while reading Michael Krasny’s new book, Let There Be Laughter, I came across the Yiddish word naches, which Krasny defines as “the joy and pride a parent derives from a child’s accomplishments.” High on a mother’s list of accomplishments for her daughter would be the production of beautiful grandchildren. It was an ‘Aha!’ moment. I’d been re-reading some of my 1967-68 letters to parents (my mother saved them all and gave them back to me) and thinking about the strained mother/daughter relationship the letters revealed.

The occasion was our first visit back to New Zealand. It had been seven years since we left our birth country, and twelve years since I had spent more than a week or two with my parents. In the meantime I had earned an advanced degree, begun a career as a writer, married, moved to England, had a couple of children, moved to California. I had kept in touch faithfully through fortnightly letters but had had none of that face-to-face interaction that helps define a relationship.

I was wildly excited about the trip:

18 Sept. 1967

I have a bit of news that I have been saving up, partly because I still scarcely believe it myself – we are hoping to come for a visit to NZ about the middle of next year, probably in May. It will only be for a month – you get a cheaper excursion rate for 28 days – but hope that will be long enough to see everybody again, & for the children to sort out who all the vague names of grandmas, uncles, etc. are – David [our 4-year-old] has them hopelessly confused at the moment.

1 Oct. 1967

[On news that sisters & cousins were having babies] It will be fun to meet all these new members of the family – they certainly seem to be mounting up.

31 Oct. 1967

[re Christmas presents] Like you, finance is a bit low this year – as you can imagine, we are needing to save very hard for this trip.

My next letter has a firmer tone. With the help of a marriage & family therapist friend (thank you, Linda G.), I’ve been researching the psychology of mother/daughter relationships and discovered the Jungian concept of individuation, the process of becoming aware of oneself as a being separate from one’s parents. I also learned that tensions are normal in the parent and adult child relationship during this process of separating and setting boundaries.

17 Nov. 1967

I gather that preparations are already being made for our homecoming in May. I hope you realise that our time is going to be extremely limited. We hope to divide most of it between you & [my husband’s mother], but also must go to Christchurch for a few days, and also have friends around the country that we hope to visit. So you would do well to reckon on about a week (don’t forget flying time is included in the 28 days). This week will have to include relations too. The plan for an open day or weekend sounds a good one. I had better make it plain from the start that, apart from our immediate brothers & sisters, and possibly grandparents if they are too infirm to travel, we are not going to do any relation-visiting. For one thing, it wouldn’t be fair to the kids, dragging them round from one set of strange faces to another. If you are going to get to know them at all, which from our point of view is the purpose of the visit, we will need a quiet domestic atmosphere with as few strange faces as possible. It took David four months to adjust to living in this country. Also, two days of being an exhibition piece is about as much as T. or I could stand – we are pretty unsociable types!

Here’s where the Yiddish concept of naches comes in. Looking back, I realize now that it mattered deeply to my mother to be able to show us off. She had never seen our children, her first grandchildren, other than in photographs, and she had idealized them. But as a young mother, I was having none of it:

5 Dec. 1967

Glad you see my point about visiting relations, though reading your letter again I have a suspicion that you intend to have them turning up all the time anyway. If this is so, please think again. I know, Mum, you love to have your family about you, and find it hard to understand my attitude. But to me my family is my husband and children, and next, my parents and brothers and sisters. Now I shall be delighted to meet all my uncles and my cousins and my aunts, but since practically all of them are almost total strangers, it would be much easier on us to restrict their visits to a definite two days, and leave us free for the rest of the time to do what we came for, which is to visit you.

In my psychology reading I came across another concept, filial maturity, explained as:

1) By early adulthood, particularly in the 30s, taking on the responsibilities and status of an adult (employment, parenthood, involvement in the community), the child begins to identify with the parent.

2) Eventually, the parent and child relate to each other more like equals.

When I wrote these letters about our forthcoming trip to New Zealand I was 29. After fifty years of being a mother and a grandmother, I now understand why my mother and I were at odds. I’m sorry she had to deal with such a difficult and demanding daughter. I also know this was the way it had to be.

A roof and a meal in 1968 dollars

While rereading letters dated early 1968 from California to my New Zealand parents, I discovered a conversation about the cost of housing and the cost of living generally. If you’ve seen the current astronomical real estate prices in the San Francisco Bay Area you will be mind-boggled at the numbers. For that matter, housing prices have also risen dramatically in New Zealand cities. (To take inflation into account, multiply the US 1968 numbers by 7.2)

The conversation started with mention that friends in the apartment complex where we lived had bought a house.

2 Jan. 1968

On Sunday we spent the afternoon at the J___s’ new house – they have managed to acquire a lovely rural acre running down to a creek – we are very envious.

26 Jan. 1968

You asked about the price of housing. Well, the J___s got theirs extremely cheaply, because of some easements on the property – power lines restrict building on one corner, and a road may possibly go down the side of it. Normally such a place would go for between $45,000 and $50,000 – they got it for under $35,000. Housing is generally pretty expensive here. If you want a genuine or potential slum you only have to pay about $18,000, but the vast majority of ordinary middle class suburban houses – about equivalent to the typical NZ suburban house – come in the range $22,000 to $28,000. New houses in this area, that is, the west side of the [Santa Clara] valley, are all $35,000 and up. Down payment is between 10%–25%. Which puts us out of the housing market for some time.

Just for comparison, what would an equivalent house in NZ cost now? The outer suburbs of Auckland or Wellington, for instance. It would also be interesting to compare costs of living – could you find out for me how much it would cost per week to keep house for a family like ours, for instance?

27 Feb. 1968

Thank you for the list of prices etc. Costs certainly seem to be fairly high. Your power bill is about the same as ours, and so is the telephone. Houses in NZ seem to be about half our price, but rents considerably lower – we are paying $160 a month, or $40 a week, and this is pretty reasonable for this area. To get a house we would have to pay $225 or more.

Your food bill is certainly much cheaper than mine. I have $40 a week for housekeeping, of which about $20 goes on groceries, $4 on fruit and vegetables, $5 on meat (and this is pretty frugal – we practically never eat steak, for instance. In fact, our standard of living hasn’t changed much from what it was in England.) The rest goes on miscellaneous sundries – sewing notions [I sewed all my own and the children’s clothes], postage, haircuts – at $3 a go for an ordinary cut it’s just well I don’t go in for sets, perms, etc., and the boys’ hair I cut myself.

…This seems to be turning into a grouch about costs, which is not really fair, as salary levels are comparably higher. At present we are managing to save about 10% of Tony’s salary, which is better than we have ever done.

Those new houses in Cupertino that in 1968 were selling for $35,000 are now listed at over $2,000,000. That’s eight times the inflation rate. Economists might say that’s the law of supply and demand.