Archive for the ‘domesticity’ Category

The shapes of family

I still remember the tongue-lashing my teenage cousin and I received when we defended our widowed grandmother’s decision to file for divorce from her second husband. If the two of them couldn’t get along, we saw no reason why they should have to stay together. Mothers and aunts rounded on us. We didn’t know what we were talking about, they scolded. Grandma was a disgrace to the family. The Mother’s Union of our Anglican Church was going to throw her out, and her daughters were ashamed to show their faces in town.

Tauranga, New Zealand, was a tightly traditional little town in the 1940s and 50s, when I was growing up. Fathers worked, mothers stayed home with children. I didn’t know any single parent families. If there were divorcees, they were invisible. So were lesbians and gays.

My social environment in England was almost as sheltered. My friends were other young marrieds with small children. Our close of new row houses was filled with intact families like ours.

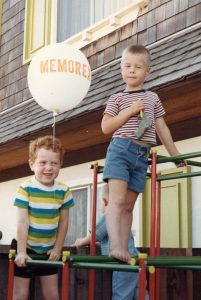

When we moved to Cupertino, CA in 1967, we lived in a complex of townhouse apartments. Each apartment had a 20 ft. by 10 ft. fenced yard. Our yard was filled with a climbing tower, a sand box, sundry tricycles, pushcarts, and other paraphernalia to keep our two small boys entertained. The neighbors helped open my eyes to other family structures: single parents, grandparents raising kids, abusive relationships.

The memory of my grandmother’s divorce comes back to me as I read a letter to my parents. After thanking them for our two-year-old’s birthday gift, I wrote:

17 Nov. 1967

Simon had a lovely little birthday party – a lunch for three little friends – after school the apartment is invaded with older kids, which would have caused problems. We seem to run a regular play centre here, what with the climbing tower and sandbox, and the new easel, with apparently unlimited supply of crayons & paper. However, the opportunities for recreation are so limited in these apartments, and so many of these kids from broken or otherwise mixed-up homes, that I guess its our contribution to the community.

There’s a self-righteousness tone to this comment, an indication of my awakening to the variety of household shapes in this new environment. A hint of defiance too. I wonder, was I getting back at my mother and aunts for their dismissal of my grandmother’s decision so many years ago?

In Praise of Parks

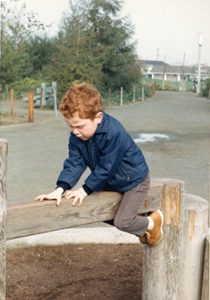

Having spent all their little lives in a place where parks had prim Keep Off The Grass signs and irate men in bowler hats with sticks enforced The Rules, my children were enchanted to discover the parks and playgrounds of their new home.

In the 1967, when we arrived in California from England, California State Parks was going through a huge expansion. Appropriations from the General Fund and a 1964 recreation bond provided well over a hundred million dollars for land acquisition and development. The government budget analysis for 1967 comments:

In the immediate future, the most pressing need of the state park system will be to provide funds for access and minimum development to enable the public to use lands now owned or currently being acquired. The existing state park system has a potential for development of about four times that of existing facilities.

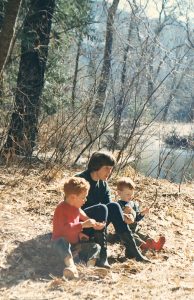

With an expanding population, local governments in the Santa Clara Valley were also opening new parks and playgrounds as rapidly as they could. It was a fine time to be kids. They had their choice of playgrounds within easy driving distance: the one with the great swings, or the one with the good bars to climb on?

Cooking out at a forest park was one of our favorite activities. We bought a cheap little hibachi, loaded up a picnic and were off to explore.

At weekends, if the weather was hot in the valley, we might go over the Santa Cruz Mountains to the beach, remembering to take warm jackets since the fog was likely to roll in. Again choices, choices: Pescadero State Beach, or San Gregorio, or Half Moon Bay, Natural Bridges, Seacliff, Manresa…? Well before the California Coastal Act of 1976 declared that the permanent protection of the state’s natural and scenic resources is a paramount concern to present and future residents of the state and nation and that it is necessary to protect the ecological balance of the coastal zone and prevent its deterioration and destruction, the beach parks in our part of the state were already a beloved treasure.

Looking back, I recognize how innocent we were about land use politics, environmental pollution issues, climate change. Now more than ever, those parks and beaches, and the creatures living in them, need our support.

For love of a bug

A 1961 VW Beetle, the same year as mine. Image from https://vwsinportland.wordpress.com

I didn’t learn to drive until I was 29 and living in California. I had managed pretty well without a car until then. During my university years, I spent practically all my vacation time working at a fishing camp accessible only by boat. One year when I spent a week at home, my father gave me a few driving lessons. However, he lost interest when, while practicing backing in a field, I indented the shape of a tree trunk into the back bumper of his car.

Public transport worked just fine for my job in Christchurch, New Zealand, and for getting around when we lived in England. When my husband bought a Triumph Herald for his commute to work, I had twinges of conscience that I should learn to drive it. But then we’d take an excursion into London, and the huge traffic circle at Hyde Park, with its multiple lanes and multiple exits, would do me in for another six months.

Then we moved to California. One child was just four, the other eighteen months. Between our apartment and the distant shops were no sidewalks, just the weedy, lumpy verges of old orchards. I scurried to find a driving school and a babysitter. My letters to parents chronicle the story, which is probably familiar to readers who learned to drive as teenagers:

30 May, 1967

Tony has been out car-hunting tonight. He has been driving a rented Ford Mustang, & has been so pleased with it that has decided to buy one for himself. Here there is no fixed price for new cars – it’s a sort of Eastern market of haggling & bargaining, & a buyer’s market at that, so it’s a matter of going round the various dealers to see what they will offer.

18 June, 1967

I have passed the written part of my driving test. Margie Mandeville (neighbour with whom I have got very friendly) took me down to the Dept. of Motor Vehicles on Friday morning & looked after the kids in the car. Quite a good system – before you start learning to drive you have to get an instruction permit, which requires passing a written test on the Highway Code, & eyesight test. I’m a bit apprehensive about starting lessons, but guess I shall get over that.

30 June, 1967

My driving lessons are going quite well – I have an hour nearly every day, will probably take my test later next week. Very concentrated course, a bit of a strain, but am apparently managing quite well.

10 July, 1967

I am now the proud holder of a California driver’s license – passed my test this morning, with quite a good mark, considering nervous tension – 81%, passing grade is 70%. Quite a sensible system – you start off with 100 points, & get docked a set number of marks for each kind of error. Mind you, Tony passed the test the other day with 95%! Anyway, I am feeling very pleased with myself.

I am now itching to get my hands on the wheel of that Mustang – Tony has promised to let me have a go at it, provided I don’t mash it up. As I learned on a Mercury Comet, which is slightly larger, it shouldn’t be much problem. We are also going car-hunting for an elderly VW for me – they are very popular around here & have a good reputation for reliability & dealer service – this is a problem with many imported cars. What do you think, Dad, about maintenance costs on a VW of say, 1958? This is available at about $500; compared with a 1964 at about $1,000 (can’t afford anything more recent). I am really looking forward to being more mobile, & Tony is too – he finds weekend shopping a drag, when we could be swimming or sunbathing or going somewhere interesting.

20 July, 1967

I have been having fun playing with my new toy – a bright red 1961 VW. It is in very nice condition, & the engine runs beautifully – the dealer had just spent $200 on it, including a big valve job – I gather that this is the thing most likely to go wrong with these VWs. It seems your advice to go to a VW dealer is just as valid here, Dad – is it true that they are responsible for getting the car into decent running order before they sell it? We took it out & checked it for all the usual faults, could find nothing wrong but a non-functional speedo, which Tony fixed with $2 worth of cable, & talked them into throwing in a new set of tires. Tony is going to take it into an auto-probe centre next week & have it thoroughly checked out, but so far we are very happy about our $850 worth. I have had one lesson from the driving school, & managed the gear shift quite well, & now it’s just a matter of practice. I have been getting in a bit of practice on the Mustang too – just as well, as we landed up in East San Jose on Sunday, buying this car (left the kids with a babysitter) & finished up with two cars to bring home, so I was landed with the Mustang. There seemed an awful lot of car for one scared little me – much more than when I had someone with me, but quite enjoyed myself once I got over being scared.

I loved my little bug. The upholstery was torn, so I made slipcovers from brightly striped canvas. I quickly mastered the freeway system, and went everywhere I needed to go. It wasn’t until some years later, when we traded in the VW for a Mercury Montego station wagon, that I discovered some cars get more respect on the freeway than others. No longer was I being cut off by trucks, or prevented from making a lane change. Interesting, the social hierarchy of the roads.

When domestic and literary lives collide

Among the battered manuscript boxes in my old black filing cabinet, you won’t find the draft of my first novel. It’s gone, the victim of a long-standing conflict for women between the dream of a writing life and the urge to domesticity.

Katherine Mansfield was my heroine and role model. Born in New Zealand in 1888, she too had embarked for England as a young woman determined to make her name as a writer. Through privation and illness she continued to write and publish story collections that made her famous. I could do that too, I told myself.

But there was a variation to our respective histories I had not counted on. In New Zealand before we left, I had given birth to a stillborn daughter. Looking back, I understand that depression fueled by guilt and buried grief over this loss exacerbated the homesickness and culture shock I experienced that first year in England. My unsuccessful search for a writing job did not help. In traditional wifely fashion, I had held off until Tony found work, in a company based west of London, then scrambled, in an unforgivingly tight rental market, to find us somewhere to live nearby. By the time we were settled, a lengthy daily commute into London seemed overwhelming.

I also ran into a catch-22: even though I had been a member in good standing of the New Zealand journalists union, no paper or magazine in London would hire me unless I was a member of the British journalists union, and it was not possible to join that union without first having a job on a paper. When the local newspaper in Windsor turned me down for a posted job because I refused to promise not to get pregnant and ‘waste their time,’ I decided the best thing to do was to start work on my novel and to have another child. I believed, naively, that I could handle taking care of a child and having a writing career. In retrospect, any kind of job would have made better economic sense. We were desperately poor, but the dream of making my way as a writer still held.

I don’t remember much of the plot of that first novel. Two main characters were New Zealand immigrants to England, like ourselves. There was also another couple, and some symmetry of cross-coupling, probably influenced by the Iris Murdoch novels I was reading. I remember feeling uneasy that the plot line was uncovering a sense of dissatisfaction and disillusionment in my own life and that I didn’t know how to resolve the story.

By the time we left England five years later, my world revolved around our two small sons. I found it harder and harder to find time to work on my novel. I pushed aside the dissatisfactions with my own life that the novel echoed. In California things would be different, I told myself. I would devote my life to being a good mother. One bleak winter afternoon as we were packing up to leave the tiny house we had bought in Egham, Surrey, I came to a decision. I was alone, Tony at work, our older son playing at a neighbor’s house, the baby asleep upstairs. Outside under a lowering sky, the baby’s nappies, frozen into boards, hung motionless on the clothesline. Inside, a small coal fire burned in the grate. I sat on the floor in front of the fireplace and fed the unfinished draft of my novel page by page into the flames.

By the time we left England five years later, my world revolved around our two small sons. I found it harder and harder to find time to work on my novel. I pushed aside the dissatisfactions with my own life that the novel echoed. In California things would be different, I told myself. I would devote my life to being a good mother. One bleak winter afternoon as we were packing up to leave the tiny house we had bought in Egham, Surrey, I came to a decision. I was alone, Tony at work, our older son playing at a neighbor’s house, the baby asleep upstairs. Outside under a lowering sky, the baby’s nappies, frozen into boards, hung motionless on the clothesline. Inside, a small coal fire burned in the grate. I sat on the floor in front of the fireplace and fed the unfinished draft of my novel page by page into the flames.

A sisterhood of neighbors

Would she be able to watch my toddler for an afternoon while I went to a doctor’s appointment, I asked Margaret, my next-door neighbor in the block of new row houses we’d both recently moved into in 1965. An odd look came over her face, and a blush reddened her cheeks. A pause. “Actually, I have a doctor’s appointment that afternoon too.” Another pause. I don’t remember which of us said it first: “I think I’m pregnant again.”

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

An easy solution: we went to our appointments together, to the same doctor, taking turns to supervise our infants (her daughter only three days younger than my son) in the waiting room. Our second children were born within two weeks of each other. Another neighbor, Jo, took care of our two-year-old then, while my husband was at work. When Jo had another baby the following year, it was I who minded her two little girls.

Not having family in England to call on for help, I am forever grateful to this sisterhood of neighbors. Most of the women in our little close of twenty houses were stay-at-home mums with small children. We drank coffee together in the mornings and shared how our brains were turning to mush. Our children ran in and out of each other’s houses. We took care of each other.

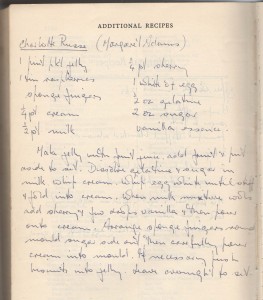

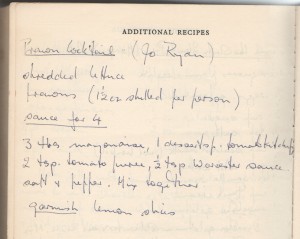

On the back pages of my English cookbook are two recipes, one for a Charlotte Russe from Margaret and a prawn cocktail from Jo, both classic 1960s recipes. I remember the occasion vividly. My husband Tony had accepted a position in California. We were waiting for our US green cards to come through –a nerve-wracking saga that I’ll write about sometime. Meanwhile, his prospective new boss was passing through on his way home to Denmark for Easter, and wanted to meet Tony. A dinner invitation was obviously required. But what to serve? In a panic, I turned to my sister-neighbors. They held my hand and helped me through planning a menu. Prawn cocktail to start, and Charlotte Russe for dessert. For the main course I probably served roast lamb, a traditional New Zealand staple.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

The dinner was a success, though I suspect that the Danish boss, having gotten used to casual Californian ways, was a bit overwhelmed by the formality of it. But he was very gracious, and we had a pleasant evening. I couldn’t wait to share how it went with my neighbors the next morning.

The woman on the moor

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The year was 1966. Knowing it might be our last year in England, our family (husband, two infant boys and me) took a summer trip through England and into Scotland, staying mostly in private homes that offered bed and breakfast. A farm in the Peak District of Derbyshire. Across the Yorkshire Dales to Huddersfield and Keithley, from whence my paternal grandfather had emigrated as a young man to New Zealand. Up to a gray stone village on the moors to take tea with a sweet great-aunt who had married and stayed behind when her siblings left, and whose knowledge of the whole New Zealand branch of the family put me to shame. The Lake District, lowering with storm clouds and redolent with Wordsworthian cadences. A stone circle near Keswick. Hadrian’s Wall, a loch in Scotland. Yellowing pictures now fill a photograph album.

The little roadside shop was somewhere in the northern hills of England, on our way home. A gray, damp day, a gray, bleak building. Nothing much else around. We all needed a break from driving, so we stopped. Quickly bored with the arts & crafts contents of the shop, our toddler and the baby drifted outside with their father. I lingered, drawn to the young woman attendant, who sat at a table threading beads into a necklace. A knitted shawl around her shoulders, long mousy hair falling in a braid down her back. We chatted. She had left an unhappy relationship and was determined to survive on her own.

She had the confidence I lacked. Brought up in a conservative culture and married young, I was struggling with a sense of powerlessness in my traditional wife-and-mother role. There were times I felt trapped, and thought of escaping with the children back to New Zealand. But this would have felt like defeat. Besides, it was impractical. I had no money to pay for fare, no clue about how I would manage on my own once I got home.

My encounter with the woman on the moor was brief. I never learned her name. But the amethyst ring symbolizes an unspoken pact between us. What I gave her was good wishes and payment for her work. What she gave me was confidence that I too could find my inner strength. This is what I remember when I wear it.

A season for love (and cake)

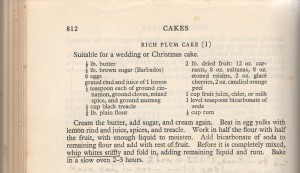

What I loved about living in England as a young woman in the 1960s was the traditions around the holiday season. On foggy street corners in London, vendors with portable braziers sold roasted chestnuts, hot in the hand, but so good. Butchers’ shop windows would fill with huge hams, neighbors’ kitchens be redolent with the aroma of figgy puddings steaming on stove tops. I would pull down the English recipe book my mother-in-law had given me and assemble ingredients for my Christmas cake: an assortment of dried and candied fruit, spices, juice, eggs, butter, brown sugar, treacle, flour, and the all-important dash of rum.

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

Making a proper English fruitcake is a multi-day affair. First, the careful preparation of the tin and timing of the baking so that it doesn’t go dry. My Constance Spry Cookery Book devotes several pages to these matters. Then the making of the cake itself. Several days later, in preparation for icing, the cake is brushed with a warm apricot glaze. My cookbook declares:

The object of this protective coating is to avoid any crumb getting into the icing and also to prevent the cake absorbing moisture from the icing and so rendering it dull.

Next comes the layer of almond paste or marzipan, rolled out like pastry and smoothed on with the palm of the hand. A day or three later comes the smooth base coat of royal icing, made by mixing egg whites and lemon juice with the sugar. When this layer is perfectly stiff and hard the decoration is piped on.

When we moved to California, I continued to make Christmas cake for a few years, until I realized that fruitcake in America is the butt of seasonal jokes and that my lovingly prepared cake sat in the pantry scarcely touched. I am grateful that until his death a few years ago, my late brother-in-law Derek Heckler, who lived not far away, continued to bake and share a splendid traditional cake.

As earth and sun roll toward another pausing time, let us remember dear friends and family members now gone, and reach out in love to those still with us. However you celebrate the season, may it be filled with the traditions you hold dear.

Oh, to be shoe-less in the summer sun

My sister Alison’s family, gathered in New Zealand for Christmas. It’s summer there, that time of year. Note the absence of shoes.

My old black filing cabinet has yielded a treasure: the carbon copy of a 1960s letter to a newspaper editor. Reading it again, I’m struck by how much it reveals about my homesickness for the more casual lifestyle of New Zealand and my resentment of the strictures of English custom. I was reminded of these differences when my sister Alison, who lives on a beach north of Auckland, posted on Facebook a photo of her gathered family, and American friends of the family joked about the lack of shoes. Here’s the 1964 letter:

The Women’s Editor

The Guardian

Manchester

Dear Madam,

As a fellow colonial I share [Guardian feature writer] Geoffrey Moorhouse’s feelings about English clothing habits. The conformity begins at an early age. This summer my one-year-old toddler and I have been subjected to cold stares and even sarcastic comments from total strangers. The cause is his shoe-less feet. I am obviously considered a poor mother, for not providing leather for his feet, and looking round, I noticed that even during the hottest days, while my infant sat comfortable in only napkin and sunhat, most of his contemporaries were firmly laced into heavy shoes, and many were even inflicted with neatly buttoned shirt and tie.

I am not against shoes on principle. Now that the weather is turning cold, my son wears shoes and socks with his long trousers. But I do object to this pressure to dress young children according to society’s idea of respectability, disregarding the dictates of the weather.

I don’t go barefoot in Mendocino. It’s cold here, and there’s burr clover and native blackberry underfoot. But sometimes I miss those carefree New Zealand summers of my youth.

The red stain of near disaster

Whenever I see old blackberry canes, dark red as the stain of their summer juice, I remember blackberrying in England when my son was small, and a dark red guilt sweeps over me. I described our expedition in a letter to parents:

8 Oct 1965

We went blackberrying on St. Ann’s Hill, not far from here. Got a lovely lot—have been busy making jelly, pies, etc. David had a wonderful time—it was so sweet to see the solemn single-mindedness with which he set about collecting his berries—and he didn’t eat a single one until Tony offered him a handful—to comfort him when he tumbled down a slope into a patch of brambles.

Modern American parents would probably be horrified at how lackadaisical we young mothers in England were about supervising our children’s play. Once the daddies were gone to work, our little close of twenty-eight row houses was almost completely free of traffic. The kids, twenty of them under school age, ran in and out of each others’ houses and romped together across the grassy front yards.

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

While Tony, who had come home from work for lunch, went to tell the mother of the other child what had happened, I tried everything I knew of to make our baby throw up. Nothing worked. We called an ambulance. Since I was within a week or two of giving birth to our second child, a neighbor, seeing the ambulance, came over to wish us well. I am still grateful that when she learned the story, she called the police, and still guilty it hadn’t occurred to me that other children might be involved. Some days later I wrote to parents:

Watercolor illustration by Barbara Nicholson in The Oxford Book of Wildflowers, Oxford University Press, 1960. Shown are: Comfrey, Common Mallow, Musk Mallow, Deadly Nightshade, Duke Of Argyll’s Tea Plant, and Woody Nightshade.

13 Oct. 1965

The police organised all the rest of the kids in the close whose parents couldn’t prove they were somewhere else that morning into another convoy of ambulances for a mass stomach pumping session. About a dozen altogether involved, of which four (including David) were confirmed cases, though they decided to keep the whole lot overnight for observation, just in case.

Meanwhile the newspapers had got hold of the story. We refused to see them at the hospital, but when we got home about 7:00—completely exhausted, & having had nothing to eat since breakfast—we were invaded by a posse of reporters. A highly garbled & exaggerated account appeared the next day. I suppose it’s not every day one makes the front page of the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, & the BBC News, but I shouldn’t care for the honour to happen again.

Anyway, the story ended well—all the kids were discharged the next morning, with none but the hospital staff any the worse for wear—in fact the sister-in-charge of the children’s ward where the confirmed cases were confessed that she hadn’t known that four such tiny boys could get so involved in riots and punch-ups all up and down the ward, and they were very pleased to see the back of them.

Fingernails on glass

The visiting baby, almost two years old, sat alone and silent by the ribbed glass door of our row house in Egham, on the outskirts of London. He paid no attention to our chatty, energetic infant of the same age, nor even to his parents. Instead, he ran his tiny fingers obsessively over the ribs of the glass. Watching him as I fixed tea for our guests, I was uneasy.

A letter to my parents dated 20 April 1965 says nothing of this unease. Instead:

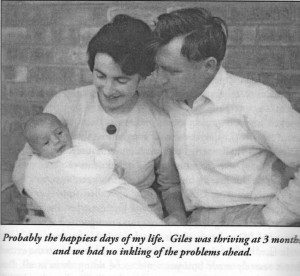

We had visitors on Sunday – Steve & Derek Shirley & their little Giles, who is the same age as David. We hadn’t seen them for quite a while, & had a very pleasant day.

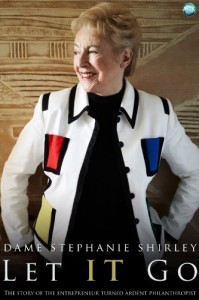

That was the last time we saw the Shirleys. Recently I have been reading Dame Stephanie (Steve) Shirley’s memoir Let IT Go, to try to understand what happened to our year-long friendship. The answer is devastating.

In early 1964 I had interviewed Steve by phone for an article that ran in the Guardian about women programmers and her new business Freelance Programmers. A few months later I gushed to parents:

30 April 1964

A couple of weeks ago we went to visit a very pleasant couple – the woman I interviewed (over the telephone) for my article on computer programmers. She has a baby the same age as David, and also works at home making up programmes – that is, the detailed instructions to be fed into a computer to do a required job. Anyway, we liked each other very much even over the phone, and she invited us to a meal to meet properly. They have a marvellous little stone cottage up in the Chilterns, right out in the country, with apple trees and daffodils, low oak beams, a huge log fire, and a grand piano squeezed into the front parlour. It sounds like a setting from a romantic novel, and that was the feeling even when we were there, that everything matched so well that it couldn’t be quite real. And a remarkable affinity too, between us as people. A bond to start with of course — it was the interest of her story that got me a place in the Guardian, and she credits me with the terrific boost to her business – she now has 20 other home-bound women working for her, and is forming herself into a limited company, and with giving her the confidence to get started. Then Derek is also a physicist [like Tony], reserved, very musical, and Steve and I found that our feelings and ideas agreed on all sorts of points.

At that time Giles and our David were eleven months old. Steve writes in her memoir:

The catastrophe had crept up on us. It must have been in early 1964—when he was about eight months old—that we first began to worry, on and off, that perhaps Giles was a bit slow in his development: not physically, but in his behaviour. He was slow to crawl, slow to walk, slow to talk; he seemed almost reluctant to engage with the world around him. These concerns took time to crystallise—as such concerns generally do—and the first time I went to a doctor about them I couldn’t even admit to myself what was worrying me. …

My letters for the rest of 1964 are full of references to our new friends: visits back and forth, parties, conversations. In June I wrote: We liked them even more, if possible … isn’t it strange how people sometimes just click.

Meanwhile, Steve writes:

By the end of that year, however, there was no avoiding the observation that Giles was losing skills he had already learnt. … [He] had never become chatty. And now he fell silent. …

Months of desperate anxiety followed, in which there seemed to be little that we could do except fret. …

My lovely placid baby became a wild and unmanageable toddler who screamed all the time and appeared not to understand (or even to wish to understand) anything that was said to him…

By mid-1965 Giles had taken up weekly residence at The Park [the children’s diagnostic psychiatric hospital in Oxford] while the doctors there tried to work out what was wrong. Nothing I can write can capture the enormity of the sorrow that that short sentence now brings flooding back to me. …

Finally, in mid-1966, the specialists overseeing Giles’s case [at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children] delivered the devastating but unarguable verdict: our son was profoundly autistic, and would never be able to lead a normal life.

I understand now that our friendship with the Shirleys could not survive. Being with us would have been painful for them. There was too much unspoken, too much contrast between their child and ours. For a short time, we loved them. Even now, a sadness returns.

Postscript

Derek and Steve spent the rest of Giles’s short life seeking appropriate and supportive care for him. (He died at age 35.) Steve’s business flourished. She has poured her considerable wealth into philanthropy, primarily to support “projects with strategic impact in the field of autism spectrum disorders.”

Dame Stephanie Shirley: Let IT Go, Andrews UK Ltd., 2012