Archive for the ‘domesticity’ Category

Furnishing a house, 1960s style

A magazine clipping tumbles from a November 1964 letter from England to my parents. It’s the picture of a dinner service I won in a menu-planning competition. Looking at the geometric pattern on the dishes, I realize that the way we furnished the row house we bought that year has many elements of what is now recognized as a distinctive 1960s aesthetic: bold shapes and strong colors.

Having limited funds, Tony and I refurbished or made many pieces of furniture. The dining table he made was a heavy white plastic-veneered slab with straight, varnished wood legs. He built, and I upholstered, a sofa and side chairs with squared-off, simple lines, a copy of a set we particularly liked, but whose price was prohibitive. I made all the curtains from fabric purchased at Heal’s of London, the store that carried the trendiest of household furnishings. I wrote:

8 August 1964

The sitting room curtains are quite magnificent – deep orange flame colour, with a pattern called “Armada,” the formalised ships’ hulls giving the impression of a dark horizontal stripe.

A shag (another 1960s design element) area rug that matched the curtain’s colors helped warm up the coldness of the room. After battling the developer over the house’s color scheme, we had compromised on gray vinyl tile floor and plain white walls. In the kitchen and dining area, we covered the white with a geometric wallpaper. A photograph reveals more geometrics: the gray and white kitchen curtains, the cups and saucers on the counter.

We still have one platter from that dinner service I won. A few other items, mainly metal, have survived the years. A pewter jug purchased on board ship during our emigration from New Zealand to England still sits on our kitchen windowsill. To the right of the dinner service picture, behind a porcupine of cheese chunks on skewers, are familiar objects: salt and pepper shakers just like the ones we still use every day. I guess we, like these furnishings, can all be labeled “vintage.”

A long, slow saga of first-time house buyers

In 1964 my husband Tony came into an inheritance, enough to put a down-payment on a small row house in a village on the outskirts of London. From first placing a ?50 holding payment on a partially-built structure to actually moving in took seven months. Today, with the purchase, remodeling and/or building of four subsequent houses behind me, I read my letters to parents from that period with wry sympathy, thinking how universal is the impatience of a young couple buying their first house.

The first letter in the series has a page or more of excited detail.

11 May 1964

… though still with the nagging doubt that it is all too perfect, that something is sure to go wrong. Points in favor: a brand new house within our price range (rare), architect-designed with imagination (also rare), less than a mile from Tony’s job, practically in the country with a charming view over open fields to woodland, closer to London (20 minutes by fast train to Waterloo) and won’t be finished for three months by which time we should have the means to pay for it…. Small, of course, but with ingenious use of space and attractive layout …

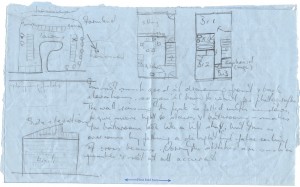

When I was growing up, my mother filled binder after binder with house design ideas and plans. We (my parents, three children, and succession of boarders – aunts, uncles, and family friends, often two at a time) lived in a rental Craftsman bungalow built about 1910: two bedrooms and a sleeping porch accessible only through the parents’ bedroom and through a laundry room in which a toilet was installed late in our tenure. (Before that, we used the outhouse back in the yard.) Mum eventually built her dream house when I was about thirteen. In the meantime, I learned a lot about building design and became very familiar with architectural drawing and its symbols. I drew her a sketch:

After a month of marking time, and a thickening correspondence file, a tirade about a building society (English equivalent of a mortgage company) to whom we had applied:

8 June 1964

… the building society wouldn’t consider our house for a mortgage because it was too contemporary in design – they stick doggedly to the deadly dull conventional things. We saw one the other day, part of an estate quite near here – good solid brick, appallingly bad planning, and claustrophobically tiny windows. Mortgages no bother.

A month later, good news on the offer of a loan from another building society. However, letters for the next several weeks report a battle with the developer:

30 July 1964

… One of the hazards of a speculative development – they are very reluctant to depart from the standard model, which in this case is decidedly murky – masses of dark grays, black, browns & blues. I’m getting a bit fed-up – sick of looking at samples & doing sums – I want some action round the place.

8 August 1964

… ran into trouble over the alterations we wanted to the colour scheme – we were met with a blunt ‘take-it-or-leave-it.’ However, eventually Tony rang up & told them they were a lot of bloody-minded so & so’s, & managed to get the most important concession – the colour of the tiles on the floor. The rest of the detailing we shall probably have to rip out & replace as we can afford it. Infuriating, but the housing situation being what it is, we daren’t tell them to go to hell.

Inevitably, construction delays kept postponing the finish date for the house:

26 Sept. 1964

We went up to London on Tuesday to sign the lease & mortgage documents for the house. Exciting, but still somewhat unreal. I am ceasing to believe in the existence of the house, and find it rather unsettling to go over every other weekend or so & find they have done a tiny bit. Still no idea when we can shift in – it will probably be weeks yet.

8 December 1964

It is still hard to believe that we have actually moved in. Up to 9:15 on Friday morning, with the carrier already piling boxes into the van, we still didn’t know if we could – it all depended on the cheque from the building society being in our solicitor’s post. A strange, unreal situation to live through. However, talking to some of the other people who have moved in, they seem to have had much more trouble than us, so we must be thankful.

Anyway, in all the chaos of cancellations, postponements, etc., it was too much trouble to cancel our housewarming party, so we held it as planned on Saturday night. The earliest arrivals were detailed off to put up curtain rails, shift packing cases from the middle to the sides of rooms, etc. Quite a successful party, I think. About a dozen people (& kids) stayed overnight, dossing down wherever for what was left of the night – we got to bed about 4 am, & a few more people dropped in for brunch the next morning. Needless to say by today we are both pretty worn out, but the house is more or less habitable. Strange what an effort, both physical & mental, to make a shell filled with boxes into a habitable room.

Pregnancy under a national health system

My old black filing cabinet has yielded up a statistical treasure: an article I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper about the National Health Service’s maternity benefit program in England in 1963. I was pregnant at the time, and financially stressed, so the detailed information was particularly relevant to me. I was also young and impatient with bureaucracy, hence my railing about what seemed excessive form-filling. Keep in mind that the British pound numbers need to be multiplied by 30 to get an approximate equivalent in current US dollars.

A CHILD OF THE WELFARE STATE

Having a baby in England is a (welfare) state occasion. From the moment that a pregnancy is confirmed, an expectant mother can expect to be cared for by the state in practically every detail, down to a monetary allowance for buying clothes.

The services provided are similar in many respects to those in New Zealand [which also has a national health system]. The main difference seems to lie in the number of forms requiring to be filled out for every aspect of care. When she goes to her doctor, the woman will have already filled out a form applying to be placed on the doctor’s list, and she will have received a national health card, which she presents at each visit.

It will have to be decided where the baby is to be born. Unlike New Zealand, where admission to a maternity hospital is practically automatic, most babies in Britain are born at home. Recent reports have suggested that the infant mortality rate could be greatly reduced if more babies were born in hospital, but this raises the problem of inadequate bed space. Some effort is being made by the government to increase the number of hospitals, but it is clear that for many years yet admission to a maternity unit will be restricted to those who have good medical reasons for being there. Next in order of preference are those whose homes are inadequately provided with such facilities as running water. It is usually considered advantageous to have a first baby in hospital, although this is not always possible, and space is provided where possible for mothers having their fourth or later children.

If the baby is to be born at home, ante-natal care is provided by the family doctor and the midwife who will be attending. If the mother is granted a place in a hospital, she goes to the clinic which is run by a team of doctors and nurses from the hospital. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Expert specialised attention is given at the clinics, compared with a family doctor who may, or may not, be deeply interested in obstetrics. Against this are the advantages of seeing the same person at each visit. It is quite possible to see a different doctor at each visit to a large clinic, with the resultant irritating repetition of questions. This lack of rapport, as well as the great pressure of time on the clinics, hinders many women from asking the questions that may be troubling them. The government recently released plans to set up more clinics, which may relieve the pressure a little, but it is difficult to see how much of the mass-production atmosphere can be avoided.

During her pregnancy a mother is provided with several benefits from the state. She receives free dental treatment: normally dental patients contribute the first ?1 of their dental bills, and the health service pays the rest. She receives welfare foods—a pint of milk a day at about half price during her pregnancy, and until her child is five years old. The health service’s own brand of dried milk is provided where necessary. She is also offered cheap orange juice, cod liver oil, or vitamin A and D tablets. These products are free to those who apply to the National Assistance Board claiming hardship.

The state also provides cash benefits. To allay the hardship often suffered when a married woman gives up her job to have her first baby, and to make it easier for her, in the interests of herself and her baby, to give up work in good time before the birth, the state pays her an allowance of ?3 7s 6d a week. To qualify, she must have been paying the full rate of national insurance. It should be explained that health benefits are not paid directly from taxation, as in New Zealand, but from regular weekly contributions to a national insurance scheme. It is possible for a woman, when she marries, to contribute only a nominal sum to the scheme, and to claim on her husband’s contributions for medical benefits. However, if she chooses, she can continue to pay at the single rate, and thus become eligible for these extra benefits.

All mothers, whether working or not, are given a cash grant of ?16 to help with the general expenses of having a baby. A further sum is paid if more than one child is born. In addition to this, those women who have their babies at home are given a home confinement grant of ?6 towards the extra equipment needed.

Needless to say, all these benefits depend on the filling in of forms, and presenting them at the right time. The time limit for each benefit varies, but local national insurance offices are usually helpful about coping with the confusion.

Once the baby is born, the state’s child welfare service, under the local Medical Officers of Health, takes over. This provides a service similar to New Zealand’s Plunket Society, on a nationalised level. The child welfare service is notified by the hospital or midwife of the birth, and within a few days a health visitor calls to take particulars. (Why do they always want to know the husband’s occupation?) She also gives details of the local child welfare clinic, which provides a weighing service, and advice on feeding and other problems.

Home help services are also provided, to look after children while the mother is in hospital, or to help the mother in the home.

For those who can afford to dislike the mass production methods of the national health service, there is an alternative in private treatment. Private maternity hospitals are not subsidised as they are in New Zealand, and attention by an obstetrics specialist and delivery in a private hospital would cost at least ?100 in England, and probably much more. But even with private attention, the patient is still entitled to the maternity grants and welfare foods.

Little boys in their own words

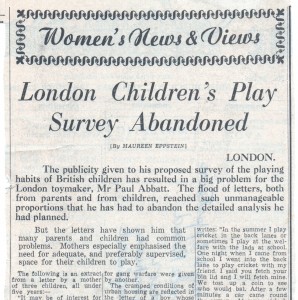

A few months after I interviewed Paul Abbatt, the London toymaker and child development theorist (see my previous blog piece, “An advocate for junk heaps”), I called to ask about his planned survey on what children actually did in their outdoor play. He sighed. The response had been so overwhelming that he’d had to abandon his plans for a detailed analysis. But he did share with me a sampling of the letters he’d received.

The follow-up story I wrote for my New Zealand paper, the Christchurch Press, was published in November 1963. It is transcribed below.

London Children’s Play Survey Abandoned

The publicity given to his proposed survey of the playing habits of British children has resulted in a big problem for the London toymaker, Mr Paul Abbatt. The flood of letters, both from parents and from children, reached such unmanageable proportions that he has had to abandon the detailed analysis he had planned.

But the letters have shown him that many parents and children had common problems. Mothers especially emphasised the need for adequate, and preferably supervised, space for their children to play.

The following is an extract from a letter by a mother of three children, all under five years:–

“It may be of interest for you to know that Crawley is a New Town—the so-called ‘Planner’s Dream.’ It is a ‘Mum’s Nightmare.’ My neighbourhood has no children’s playground, and has not had one for four years. So my children play in the road. Afternoon walks are too often an uninteresting march down roads of which the uniformity is quite paralysing.”

The mother of a boy of eight years says she could do with an attendant in the nearby park, “so that we would not be afraid to let the boy play there alone—an attendant to keep in check the bullying of older boys and help in case of accident with the swings. So, although only 100 yards away, he never goes.”

Many letters from mothers and particularly those from the children, showed children’s love for simple things, and places to make dens. A small boy of 10 gave detailed instructions on how to make a camp in a tree or cave, with the concluding remark: “Then all you need is some things to put in.” Another boy described how he and his friends caught rats on an allotment. A boy of 11 started his letter: “One Saturday when we didn’t know what to do we decided to go on a bike ride.” After several adventures they came to a secret place that one of them knew. “We went down a bank very slowly and we turned into a kind of glade. It was great. There was a stream flowing by and a smashing high tree to climb.”

Looking for the tracks of wild animals was a special memory for one boy, while the letter of another resounded with such names as Steam Engine No. 62004, Class Q.6 and Diesel Deltic, Type 5, No. D9007. Detailed rules for gang warfare were given by another.

The cramped conditions of urban housing are reflected in the letter of a boy whose favourite sport is cricket. He writes: “In summer I play cricket in the back lanes or sometimes I play at the welfare with the lads at school. One night when I came from school I went into the back lane to play cricket with my friends. I said you fetch your bin lid and I will fetch mine. We tost up a coin to see who would bat. After a few minutes a car came round the corner. At seven o’clock my mam came to the door and told me to have a bath. I went in unhappy.

“In the winter when the days are shorter and it’s dark at four o’clock I play football in the lane. Sometimes when it is raining I have a game of football in the yard. One day I kicked the ball that hard, I heard ‘smash’ one pint of milk rolling down the yard.

“Cricket is my best sport. One time my dad was having a game of cricket with me; he was in batting. I bowled, my dad hit it with such a ‘wham’ he smashed the window.”

A day at a famous cookery school

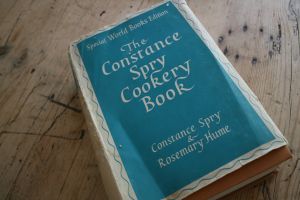

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

As an engagement gift, my future mother-in-law gave me a copy of The Constance Spry Cookery Book. Constance Spry was well known in New Zealand, both for this book and for her several books on flower arranging. When I moved to England in the early 1960s, I was delighted to discover that I lived quite close to Winkfield Place, the school of cookery and domestic arts founded by Mrs Spry and Rosemary Hume, who was also co-director of the Cordon Bleu School in London. A hook for a story for my New Zealand paper was that a NZ girl currently attended the school, so I wangled myself an invitation to spend the day. Here’s what resulted:

A day at a famous cookery school

Even at first sight Winkfield Place is charming. It is a large, white country house, set in broad gardens on the edge of Windsor Forest. Inside, all is bustle and activity. About 100 girls are going about their regular classes: cookery, dressmaking, handwork, flower arranging, shorthand and typing, and another 60 local women are attending demonstrations on cookery and flower arranging. The girls normally spend a year at the school, with a few staying on for a fourth term to take the Cordon Bleu diploma, which is recognised all over the world.

The girls, each in shining white overalls and chefs’ caps, cook in classes of 10. From one kitchen came appetizing smells of spaghetti and baked apples. From another, risotto with a potato salad, and a hazel-nut meringue to be served with an apricot sauce. Miss Hume was found in another kitchen busily stirring whipped cream into a creamed rice pudding. A dish of chopped nuts was waiting to be sprinkled on top.

Later in the afternoon, Miss Hume gave a cooking demonstration. Lotte en mayonaise, tourtiere de boeuf, chicken mousse italienne, and chamonix, were the menu for her supper party. Translated, they were a fish mould gaily decorated with gherkins and chopped parsley, a tasty steak pie, a jellied mould of creamed chicken and shredded ham, and a magnificent dessert of meringue topped with a piped “birds nest” of chestnut puree and whipped cream.

Miss Hume is described by Mrs Spry in her book (which is jokingly referred to as “the bible” at Winkfield) as the authority from whom she obtained all the cooking knowledge she had. She is a tall thin woman, with a strong no-nonsense face, a shy smile, and a deft hand with the pastry. Her guiding characteristics are commonsense and a passion for economy: she believes that all food should be treated with respect, and that to waste it is a crime. She has become expert in parrying the comments of the more snobbish of her day class audiences. One woman, for instance, wondered why she did not use fillet steak in her pie, instead of the less expensive, and less tender, rump steak. Her reply was that fillet was too good for this sort of pie, which was a “cut-and-come-again,” and that the recipe called for a cooking time quite adequate to make the rump tender. Her final comment tactfully vanquished the snob. “I for one would be grateful for a piece of this pie,” she said.

The spirit of Mrs Spry lingers throughout the house. Although few of the present students ever met her, many of the staff, who are old girls of the school, recalled her engaging personality. They spoke of the dinner parties she used to hold on the bare scrubbed table of the diploma group’s kitchen, with the candlelight gleaming on the array of copper utensils on the shelf behind. They described with amusement the clutter of treasures in her flat, and the extraordinary leaps of her conversation. “You will remember, dear,” she would whisper confidentially to one of her students, in the middle of a discussion on current affairs, “that you must always clean out the bath when you get out of it, and hang the bathmat up to dry.” Many remembered her beautiful hands, and her great skill with flowers. With it went the ability to encourage her pupils. Mrs Christine Dickie, now co-principal of the school, described how she herself was never very good with flowers. “But Mrs Spry would come in with a great heap of flowers, and say, ‘Do arrange these for me, dear.’ I would struggle with them, but the result always looked a mess, and I would beg her to show me what to do with them. ‘What’s wrong with that, it looks fine,’ she would say, giving the whole bunch a little tug that made it exactly right. Then I would be rather pleased with myself, although I know deep down that she had done it.”

Mrs Dickie was with Mrs Spry during the founding and early growing pains of the school. “She had that wonderful gift of delegating authority,” she said. “She would forge ahead with some new project, with her ‘dogsbody’ (that was me) beside her, and when the groundwork was laid, she would say, ‘Now you take over – I have other things to do’.” The result was that at her death a few years ago, the staff, although they missed her very much, found that they could continue almost as if nothing had happened. Mrs Spry made provision for this in her will. She instructed that the existing staff were to run the school for three years. If they succeeded in keeping it going, they would be permitted to continue, but if in that time the school went downhill, it was to be closed immediately.

It says much for Mrs Spry’s groundwork, and for the enthusiasm that she had inspired in her staff, that not only has the school survived, but it has had to expand to cope with the increasing demand. There is now a long waiting list for places, and the day classes, about 60 women each on three days of the week, are filled well ahead of each term.

There have been a few changes in the character of the school, and these are ones that reflect an interesting facet of English society, the decline of the debutante. When the school opened, it was regarded as a finishing school for debutantes, as a place to acquire some skill in the domestic arts before coming out into society. To a certain extent this is still true, although of the 100 girls at present at the school, only four or five are potential debutantes, and the social whirl of a debutante’s life is viewed with some scorn by the staff. The others will take up a great variety of careers. Some will go from the secretarial course to office jobs. Many of the girls in the cookery course will go into institutional kitchens, some into private houses. Some will take up other careers, such as nursing. The really dedicated cooks are to be found in the Cordon Bleu diploma class, practically all of whom want to be free lance professional cooks, and spend many of their odd moments discussing the most suitable kit of kitchen equipment to carry with them, or the prospect of gaining experience among their friends.

There are still some girls who will probably not have to earn their living. For them the course provides a convenient stop-gap between school and adult life, in a place where they can learn to grow up pleasantly and happily, while at the same time providing themselves with a form of insurance in case they do have to keep themselves. For them it is also a safeguard against the increasing difficulty of finding domestic staff. Coming from homes where all the housework is done by servants, they realise that for themselves it may be a choice between the cooking and the dusting. The girls who attend Winkfield have plumped for the cooking.

Coldness depends on what you’re used to

A letter dated April 5, 1963 has set me to thinking about how the human body adapts to temperature differences. Tony and I, and my sister Patricia, who lived with us in Windsor, England, were luxuriating in warmer weather after the Big Freeze, the coldest winter Britain had seen for over 200 years. We’d survived ice-covered walls and windows and frozen pipes, with two paraffin (kerosene) heaters our only source of heat. (There was also a wall-mounted electric heater, but it gobbled shillings and half-crowns as if it were starving.) Then our elder sister, Evelyn, arrived from Syracuse, New York, where she had been completing her doctorate. Her letter to our parents, published in her “Letters From America 1960–1963” (University of Waikato, 2005) tells the story:

I am sitting huddled over the paraffin heater in Maureen’s living room… I am still not acclimatised. This place is so cold and I miss American central heating. Here it is cold both inside and out; there is no escape. I am wearing nearly all the clothes I possess, it seems, and I sleep under a mountain of blankets, but still it is cold. In Syracuse, though it is snowing and below zero outside, once inside we took off all our heavy coats etc. and just a cotton blouse, skirt and sandals were sufficient. I am not used to wearing all these clothes all the time, but I guess, if you live here long enough, you get used to it.

On our way to England the previous March, Tony and I visited that apartment in Syracuse where Evelyn lived with fellow students from South East Asia. Dirty snow lined the streets, the sky was gray, the apartment a stifling 80 degrees.

Evelyn left space in her letter for me to add a paragraph:

…It isn’t really as cold as Evelyn makes out, although today I must admit is rather bitter. But while the rest of us are dehydrating in the hot-house fug inside, she still complains of the cold, so I don’t know what we can do.

Pat, Tony and I would surreptitiously open doors and windows, but nothing could stay open for long. We all suffered.

A little poking around the internet informs me that getting acclimated to temperature differences typically takes about two weeks, a bit longer for adjusting to cold than to heat. This makes it hard for travelers who spend only a few days in one place. People who live in extremely hot or extremely cold climates have adapted over the eons. In arctic areas they have large, compact bodies with relatively small surface areas from which they can lose their internally produced heat. In addition, they have made technological changes such as insulated clothing and houses, and cultural adaptations such as sleeping in a huddle with their bodies next to each other. In hot parts of the world people are more likely to be tall and slender, with low body mass, and to limit their activities to cooler parts of the day.

For the past 15 years I’ve lived in Mendocino, CA, where the average temperature ranges from the mid-40s to the low 60s Farenheit, and 75°F is a hot day. The county seat, Ukiah, where we sometimes have to go for business or medical appointments, is inland, or as we say, “over the hill.” There the summer temperature average is in the mid-90s and my body tells me: Nah, that’s way too hot. How can people stand it?

Good old days at the post office

In December of 1962, before there were mail codes or mechanical sorters, I worked for a week at the post office in Windsor, England, helping with the Christmas rush. I mentioned it in letters to parents:

18 Dec. 1962

…Hope this reaches you in time for Christmas – along with the other thousands of tons of mail being posted this week. I know – I have to sort the stuff. I am spending the week working in the sorting room at the post office. Very difficult job! – turning the stamps up the right way as the letters come out of the postbags. Have to work pretty hard, but it’s rather fun – very cheerful, friendly crowd – and good money.

26 Dec. 1962

…I had a very interesting week in the Post Office. Halfway through the week I was promoted to sorting, which was a bit more fun, though harder work than facing up.

Those were the days, before email, Facebook, Twitter and other social media, when the annual holiday greeting card was how one kept in touch with extended family and friends. According to Wikipedia the custom of sending greeting cards has a long history, dating back to the ancient Chinese. The postage stamp was introduced in England in 1840. Cards started being mass produced by the 1850s. From then on, mailboxes became crammed each December with penned good wishes.

Every card and letter had to be sorted by hand. Mechanical sorting, which depended on reducing the address to a machine-readable form, came in a few years after my stint at the Windsor post office: the 5-digit ZIP code was introduced in the U.S. in 1963, and England’s alphanumeric postcode system in 1966.

Communication methods have changed, and fewer greetings now go by “snail mail.” The U.S. Postal Service reports that First-Class Single Piece Mail; that is, mail bearing postage stamps, such as bill payments, personal correspondence, cards and letters, etc., declined by 47 percent in the decade 2005–2014. But that urge to reach out to those we love during the holiday season is still with us.

The many names of bread

A cottage loaf. Image from Bewitching Kitchen

Living as I do in Mendocino, CA, I am blessed with access to excellent local bakeries offering a wide variety of breads. I was amused to find in my old black filing cabinet this article I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper about discovering there were more names for bread than “white” and “brown.”

Slindon Bakery’s website has many pictures of these traditional English breads.

A Loaf by Any Other Name

London, 1962

The shelves of a baker’s shop anywhere in New Zealand will be much the same—piled high with round-topped loaves in brown or white, square white sandwich loaves, and pre-cut wrapped bread, and although North Islanders and South Islanders may argue for hours over whether the broken half of the double loaf should be called a “half” or a “quarter”, they will usually be able to make themselves understood in any bakery.

Imagine then the confusion of a New Zealand housewife confronted with the window of an English bakery, filled with loaves in an incredible variety of shapes and sizes. Some of the shapes are wonderfully decorative. There will be long thin loaves and short fat ones, some decorated with grain and some with shining glazes. There will be complicated plaits and squat little knots, enormous swelling crusty loaves, and incredibly long thin rolls that look as if they have been transplanted from the Continent.

The vagaries of English custom have established different names for these traditional shapes from town to town, and sometimes even from shop to shop in the same town.

The biggest and crustiest loaf of them all is usually called a “farmhouse.” It is a tall white loaf, often bursting from a long crack in its top. It has a close relation in the “split tin”, which does not appear to be split at all, but merely a white loaf, again with a cracked top, baked in a narrow oblong tin. These loaves are not to be confused with the “Danish”, which is not baked in a tin at all, but rises as a large oval loaf, dusted with white flour, from a flat tray.

Then there are the more elaborate shapes, such as the “cottage”, often confused with the “farmhouse”. The “cottage” is made with two balls of dough, the smaller being set like a top-knot on top of the larger. Another even more complicated one is the double plait, which contains, as its name implies, two plaits of dough set one on top of the other.

Some of the small round loaves have fascinating names. There is a ball of rich wholemeal bread decorated with wheat grains, which is called, appropriately enough, a “round meal”, but the white ball, this time with a shining brown glaze, is known as a “cob.” This is reputed to be short for “Coburg”, but where this name came from few seem to know.

The origins of other names are more obvious. One delicious scone loaf, which is sold in quarter segments of a large flat disk, is known in England as “Scotch fare”. In Wales, however, they are sold as “Welsh babs”.

A small light white loaf with a shiny glazed crust decorated with diagonal slashes, and known as a “Continental”, has a large elder brother with various titles, but usually known as a “twist” or a “bloomer”. This odd name can cause difficulties, and it has happened that an order for “A large bloomer, thank you” has met with raised eye-brows from the shops that have not heard of this title. In most cases, it is safer to point: “That one over there” and then politely ask the name of the specimen as it is being wrapped up.

A single knitting needle

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The flat was part of a semi-detached house dating from the 1870s. The bathroom could have been original. The floor was covered in black and white checkered linoleum, worn white in front of the chipped hand basin. Above the claw-foot tub was a rusty gas-fired contraption that roared to life when you turned on the faucet. The toilet was down the hall, in a more recent addition to the building.

That knitting needle haunted me, as gradually I came to realize it was probably the instrument of an attempted abortion. I longed to know the story of the woman who had pushed it through the crack between the tub rim and the wall. Did she survive?

The conservative New Zealand society in which I grew up had such deep silences around anything to do with sexuality that I was nineteen before I even encountered the word “abortion.” It was in a letter from my mother. “Look it up,” she wrote, her stock response to any question having to do with the body. Mum’s news was that a girl I knew in high school was dead: a move to the city, an affair with a married man, a botched back street abortion, septicemia, the police phoning her parents, saying contemptuously Come and get your kid.

I too have known the desperation of an unwanted pregnancy. I went into marriage in 1960 with what today would seem unbelievable ignorance about sex. The kind ladies at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Christchurch fitted me with a diaphragm and instructed me in how to use it. But the contraceptive methods of those days had a high failure rate. Within a month of the wedding I was pregnant. My new husband was furious with me for stymying his plans to go abroad and make his name in science. I was terrified of the alien life form taking over my body. I tried to recall from novels I’d read how female characters sought to make missed periods come. Scalding hot baths—I tried that. Long, long walks—tried that too, into the seedier parts of the city. If I were to find an abortionist, it would be here. But I had no idea how to find one, and no-one to ask. Besides, I didn’t want to die, like my high school friend.

In time my resistance eased. I was, after all, a respectably married woman. I began to look forward to having a baby. My husband and I postponed the date for our departure to England, and informed the shipping company that we would be traveling with an infant. When our daughter was stillborn, I was devastated, both by the loss, and by the thought that I was being punished for not wanting her in the first place. I buried my grief and guilt deep inside and got on with my life. It took me twenty-five years before I could speak about what had happened, and finally begin to mourn.

In California in the early 1970s I made the acquaintance of a lawyer who had filed an amicus curiae brief in Roe vs. Wade. Together we celebrated that important Supreme Court decision, which affirmed a woman’s right to control her own body. Today I am dismayed that so many people seem to have forgotten, or maybe never knew, what the options were for women when abortion was illegal. The decision to end a pregnancy is never easy. But I, for one, don’t want to go back to the days of the knitting needle hidden under the bathtub.

Droplets in an immigrant wave

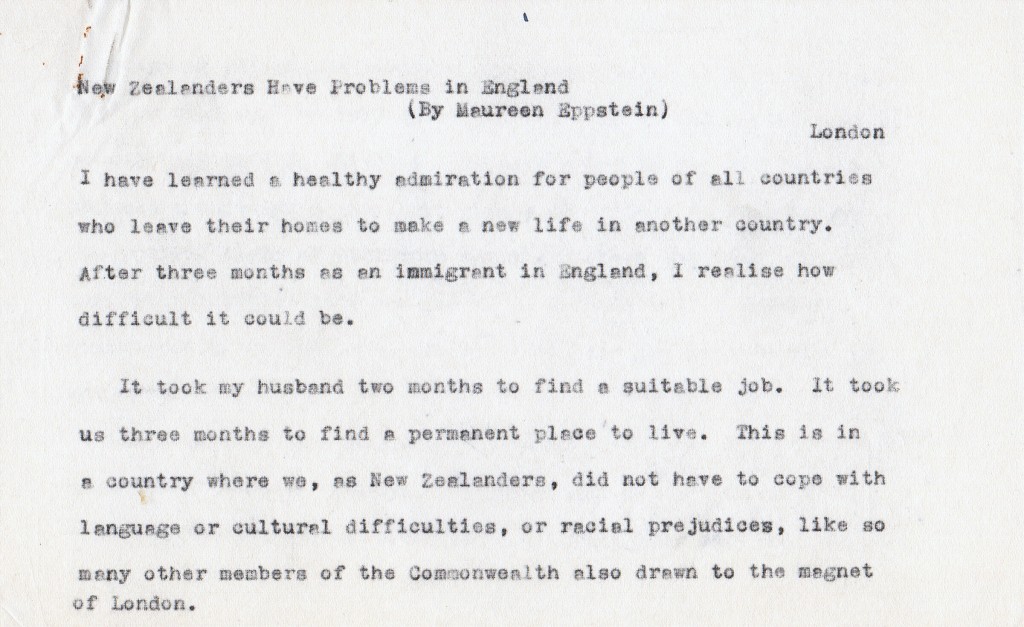

In a 1962 article I wrote for my old paper, the Christchurch (NZ) Press, a draft of which I found in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

I have learned a healthy admiration for people of all countries who leave their homes to make a new life in another country. After three months as an immigrant in England, I realize how difficult it could be.

It took my husband two months to find a suitable job. It took us three months to find a permanent place to live. This is in a country where we, as New Zealanders, did not have to cope with language or cultural difficulties, or racial prejudice, like so many other members of the Commonwealth also drawn to the magnet of London.

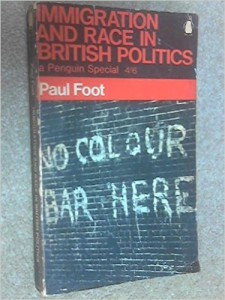

We had no idea at the time of the hugeness of the immigration wave in which we floundered. To aid in post-war reconstruction in the 1950s, Britain had recruited labor from its colonies, primarily the West Indies and the Indian sub-continent. At that time people from the Empire and Commonwealth had unhindered rights to enter Britain. However, by the late 1950s, with the British economy faltering, racial prejudice reared its violent head. The Conservative Party government proposed legislation to make immigration for non-white people harder. One aspect of the proposed bill was to deny entry to dependents of immigrant workers. Before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 could go into effect, the entry of dependents into Britain increased almost threefold as families attempted to beat the deadline. Total immigration from what was known as the New Commonwealth swelled from 21,550 in 1959 to 58,300 in 1960 and a record 125,000 in 1961.

Statistics are from Paul Foot, Immigration and Race in British Politics (Penguin, 1965)

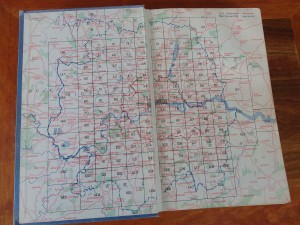

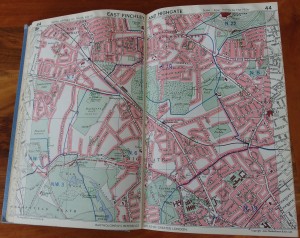

All these people needed somewhere to live. It is no wonder then that rents soared and accommodations of any sort were snapped up. While Tony job-hunted, I haunted rental agencies for a short-term apartment (or flat, as they’re called in England) and, the hefty Bartholomews Atlas of Greater London under my arm, braved the Underground and navigated the suburbs. My letters to parents are full of observations like this one:

It’s amazing how so many of the little villages that have been absorbed into the city still retain their village atmosphere – you pop up from an Underground station and could imagine yourself miles out in the country – unless you happen to be on a bit of a rise, when you see nothing but houses as far as the eye can see. One place I visited, for instance, Muswell Hill, you had to go by bus through a very extensive patch of woodland to get to it. That place I didn’t take, incidentally, because the bath was in the kitchen – covered by a lift-up board and a little frilly curtain. When I mentioned this to another English landlady she didn’t even raise an eyebrow.

My letter continues:

We have now moved out of our hotel into a bedsitter out at Hampstead, for which we are being grossly overcharged – I guess we just took it in a moment of desperation.

The rent was six and a half guineas a week (the same buying power as about $200 in current U.S. dollars.) Every piece of furniture was shaky about the legs, and the cooking facilities were two gas rings crammed into a cupboard with about six inches of counter surface. The shared bathroom was down the shabby hall. I described the landlady as

a bit of a social type – she was too busy preparing for her cocktail party last night to attend to our wants, which brassed me off considerably. Still we get on quite well with her little dog, so with a little careful handling relations might improve.

Relations did not improve. Still vivid in my mind is one of our shouting matches. I had returned from the local laundrette with clothes still damp, in spite of multiple coin feeds to the drier, and had strung clothesline around the room. In walked Mrs. Ashley-Davis. “My furniture! My furniture!” she wailed, hand to her heart. Other disputes must have followed. In a letter to parents dated May 25, after giving the news that Tony had accepted a job near Windsor, I mention that we have given notice

…after some somewhat violent disputes with the landlady, in which I managed to lose my temper – catastrophe!

Finding permanent housing proved even more frustrating. I told my parents:

…for the last three or four days we have been footslogging, railriding, bussing, and generally getting fed up in a wide arc around the area…

We moved out to a hotel near Tony’s new job. My letters for the next few weeks are full of the false hopes and discouragements of the search. Finally we got lucky: a second floor flat in a Victorian brick semi-detached house just down the hill from Windsor Castle. A roof over our heads at last!

Here’s a modern Google Maps street view of the neighborhood. It still looks much the same.