Archive for the ‘domesticity’ Category

Hurricane at Sea

We skirted a hurricane (known as a cyclone in the South Pacific) for the first several days after my husband Tony and I left Wellington, New Zealand, bound for New York on the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt.” For most of that time I lay on my bunk, so seasick I wished I were dead just to get the misery over with. In a letter to parents I scrawled: “Mountainous heaps of water piling up all over the place, wind changing direction all day …Steady old JVO bobbing around like a cork. Thank goodness I have got my sea legs at last – after the first few days of utter misery in a very stuffy cabin. Am still on a largely dry bread and water diet – lost a terrific lot of weight. But have been reading Women of New Zealand today and decided that my lot is not too bad after all. What those women had to put up with on their voyage out to NZ makes me feel rather ashamed of myself.”

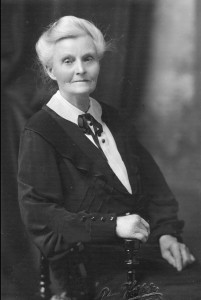

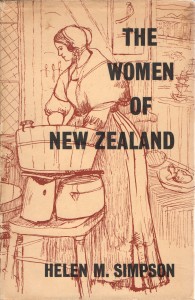

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The Ship “Kenilworth” Outward Bound for New Zealand. An illustration in Helen M. Simpson’s The Women of New Zealand, it is a reproduction of a painting by J.C. Richmond, now in the possession of the National Art Gallery, Wellington.

An early chapter describes conditions on board the emigrant ships for the four- to six-month journey from the British Isles to New Zealand. Simpson comments: “Cramped quarters ashore are difficult enough to deal with; at sea, when with every lurch of the ship ‘all things animate and inanimate’ were hurled about, children and chairs in terrifying and noisy confusion …”

Our quarters on the JVO were certainly cramped. Our lower-deck cabin had two bunks and a tiny washbasin in a space so narrow we had to take turns getting dressed. Outside in the corridor, the airless heat was rank with smells from the nearby galley. But unlike those early emigrants, we didn’t have to cook for ourselves, or bring along our own cabin furnishings.

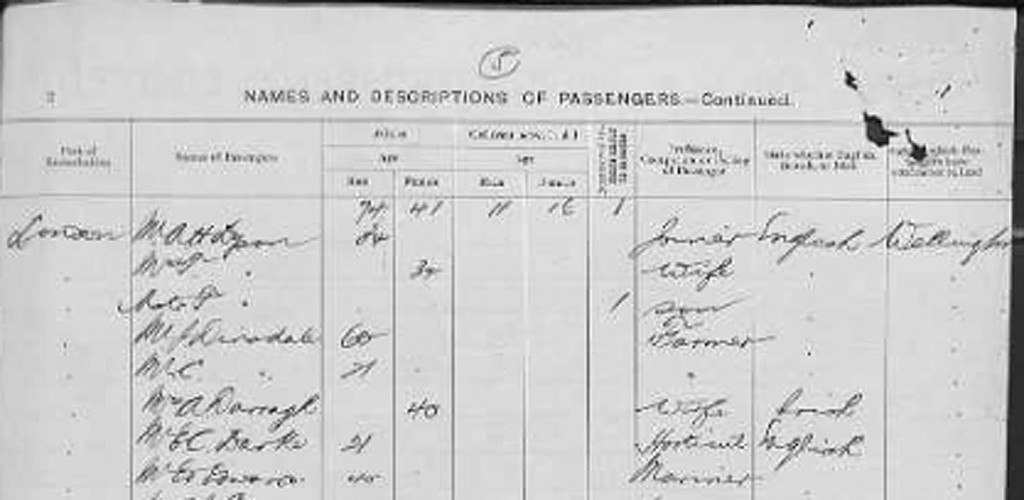

I think of my own ancestors who braved the outward journey. A hundred years before Tony and I walked up the JVO’s gangplank, my newly-married great-great grandparents, Bernard and Sarah Donnelly, set out from County Leitrim in Ireland to join hundreds of other Irish immigrants on the New Zealand goldfields. My paternal grandfather, Charles Dinsdale, emigrated from Yorkshire, England in the early 1900s. By then steam had replaced sail, but he would have set out for his new life half-way across the world with the same sense of adventure.

In her book, Simpson tells of a shipboard fire, when passengers & crew took to the lifeboats. A woman passenger wrote that, when told of the fire, ‘I folded up my knitting, put on my bonnet and shawl, and went up.’ Simpson comments: “So figuratively hundreds of other women folded up their knitting, and, putting on bonnets and shawls, quietly faced these and other perils, and all the acute discomforts of the long voyage to the new land where their hopes rested. Dangers and discomforts were accepted without fuss.”

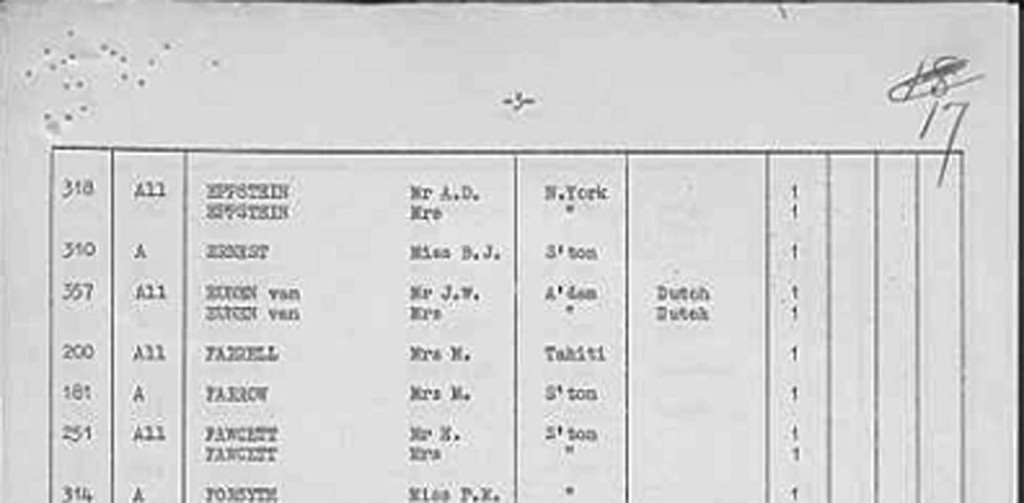

Passenger list for the SS “Corinthic” 1904. The 21-year-old C. Dinsdale (fifth name down) is probably my grandfather. From https://familysearch.org

Simpson’s standard of appropriate behavior is typical of the New Zealand society I grew up in, where we were expected to just deal with whatever hardships came our way. This is why I felt so chagrined for feeling sorry for myself.

Passenger list for the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” 1962. Our names are at the top of the page. From https://familysearch.org

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Cooking for 120 in a remote fishing camp

The Curious Cove camp, now known as Kiwi Ranch. It looks much the same as when I worked there in the late 1950s.

If you take the ferry from Wellington, New Zealand across Cook Strait and through the Marlborough Sounds to Picton, at the northern end of South Island, you will sail past the entrance to Curious Cove. At the tip of that narrow inlet is the tiny fishing camp where I worked through all my college vacations. Reachable only by boat, Curious Cove was a magical little world. The job, passed down through word of mouth by University of Canterbury women students, was perfect for this impoverished student, with board and lodging provided, nothing but a tiny tuck shop to spend money in, and a nice paycheck at the end of the season. I started off as a kitchen hand and was later promoted to second cook.

The guests, about 120 at a time, would come in for a couple of weeks. We would feed them a full breakfast, then scramble to pack lunch sandwiches for those going out fishing. Those who stayed behind got freshly baked scones with their mid-morning tea, and a salad and cold cuts lunch. By late afternoon, when the launch, “Rongo” hove into view with Charlie the skipper at the helm, the kitchen crew was already at work on the evening meal. It would be plain, traditional New Zealand fare: a roast with gravy and several vegetables, plus a dessert such as apple shortcake with custard.

Here’s a classic New Zealand apple shortcake recipe.

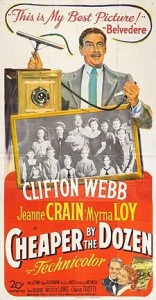

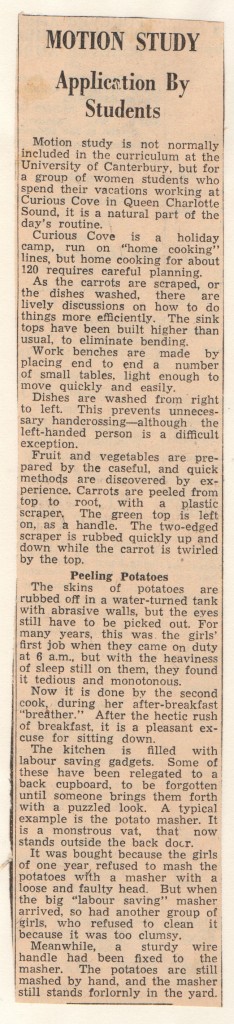

Almost everything was made from scratch. The 1950 movie Cheaper by the Dozen, the story of time and motion study experts Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and their twelve children, was as big a hit in New Zealand as it was in the U.S. Following the Gilbreths’ methods, the Curious Cove kitchen crew, being university students, amused ourselves by figuring out more efficient ways to do things.

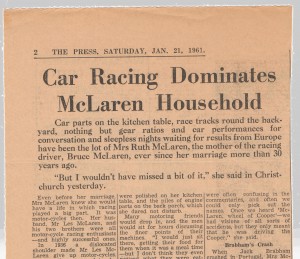

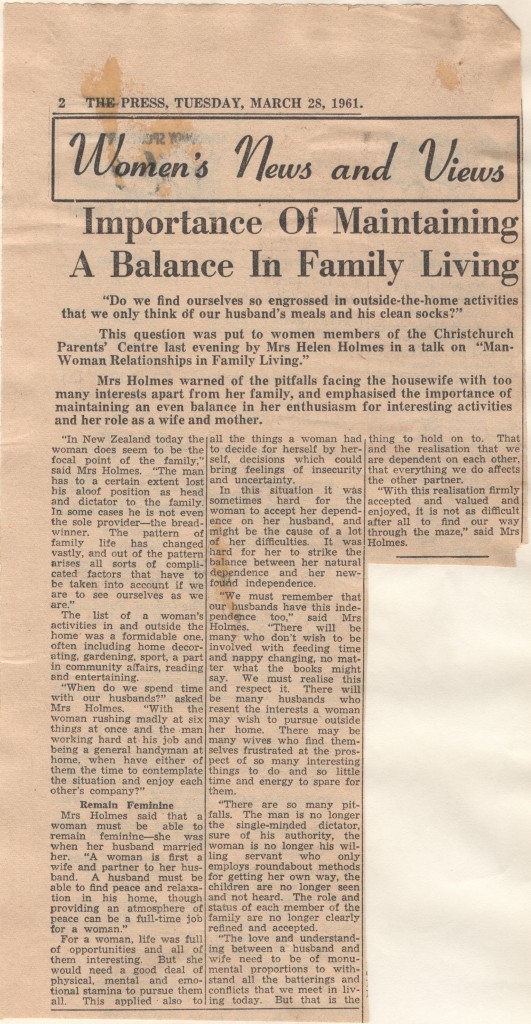

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

How I scooped the sports department

Chat with famous race car driver’s mother

Bruce McLaren in the 1969 German Grand Prix. Photo by Lothar Spurzem, via Wikimedia Commons

Getting the interview was easy. The mother of race car driver (and later designer) Bruce McLaren was my Great-Aunt Ruth, whom had known since I was a kid.

In January 1961 my cousin Bruce was back in New Zealand after an impressive debut on the Formula One circuit, where he had joined his mentor Jack Brabham on the Cooper racing team. In December of 1959, at the age of 22, he had become the youngest-ever winner of a Formula One race, capturing the U.S. Grand Prix at Sebring. He became a star overnight.

Here is a Pathé newsreel clip from that race.

The following year, Bruce came in second only to Brabham in the standings for the Formula One World Championship. Understandably, all New Zealand was agog.

Knowing via family that Auntie Ruth and Uncle Les planned to be in town to act as staff for Bruce as he worked the New Zealand racing circuit, I arranged to visit them at their hotel. Perched on the bed with our cups of tea, my aunt and I settled in for a cosy chat. Auntie Ruth was a great raconteur, and since I already knew the family history, it took little prompting on my part for her to re-tell her best stories.

The interview ran much longer than usual, but the editors at The Press published it in full. The day it was published, almost all the men from the sports department and the general reporting pool stopped by the women’s department to congratulate me. “How on earth did you get that interview?” the sports editor asked. I just smiled.

Bruce went on to establish Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Ltd. Unfortunately, in June 1970, he was killed while testing a McLaren CanAm car at his company’s site in England. His company lived on and today enjoys the reputation as one of the world’s foremost racing teams. Bruce was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall Of Fame in 1991.

I’ve appended a transcription of the interview with Great-Aunt Ruth.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The Press, Saturday Jan 21, 1961

Car Racing Dominates McLaren Household

Car parts on the kitchen table, race tracks round the backyard, nothing but gear ratios and car performances for conversation and sleepless nights waiting for results from Europe have been the lot of Mrs Ruth McLaren, the mother of the racing driver Bruce McLaren, ever since her marriage more than 30 years ago.

“But I wouldn’t have missed a bit of it,” she said in Christchurch yesterday.

Even before her marriage, Mrs McLaren knew she would have a life in which racing played a big part. It was motor-cycles then. Her husband, Mr Les McLaren, and his two brothers were all motor-cycle racing enthusiasts – and highly successful ones.

In 1936 a dislocated should made Mr Les McLaren give up motor-cycles. Two or three years later he became interested in racing cars.

World War II ended all racing, but after the war Mr McLaren did a great deal of club work in hepolite trials and hill climbs.

Bruce, aged eight at the time, was interested even then, and two years year, when he entered Wilson Home with a hip disease, he insisted on regular reports from his father.

Muddy Clothes

After Bruce came out of the home, at the age of 12, he spent 12 months with a hip sling and crutches. Football was out, much to his disappointment, but Mrs McLaren still found her share of muddy clothes to wash when Bruce and his father went on hill climbs and mud trials.

Bruce’s first car was an Austin seven, which he acquired and “hotted up” at the age of 14. That was the end of Mrs McLaren’s garden. Too young for his driver’s licence, Bruce could not drive it on the roads, so he made a race track round the backyard and through the orchard. “No garden, and no branches left on the trees, either,” Mrs McLaren recalled.

Every visitor to their Remuera home was initiated to the track, and had to endure a hair-raising and head-ducking ride round the course.

From driving-licence age on there was a series of gymkhanas, hill climbs and mud trials, Mrs McLaren said. “It was a great thrill seeing him win—we used to go everywhere with him.”

Parts in Kitchen

When Bruce was 16 his father acquired an Austin Healey, which had something special about its engine. Although Mrs McLaren has picked up a great deal of motoring jargon, she cannot remember exactly what it was. All she remembers is the gloating and loving care with which the parts in question were polished on her kitchen table, and the piles of engine parts on the back porch, which she dared not disturb.

Many motoring friends would drop in, and the men would sit for hours discussing the finer points of their machines. “I would just sit there, getting their food for them when it was a meal time—but I don’t think they even noticed what they were eating,” said Mrs McLaren.

By this time both Bruce and his father were driving the Austin Healey. There came a day when the son drove it faster than the father. that was the day when the father decided it was about time he quit.

Waiting for News

The news that Bruce had won the driver-to-Europe award caused great excitement in the McLaren household. Later, when he had gone, came the terrific strain of waiting for results.

“I just lived on my nerves the week-ends he was racing,” said Mrs McLaren. Always at the back of her mind was the fear of a crash. “We have great faith in Bruce’s driving ability, but there are always things beyond his control. But he has not had an accident yet—touch wood.”

The McLarens waited anxiously for the first B.B.C. news in the morning, since the results of the championship races were always announced, and the news would come faster than a cable.

Visit to Europe

Two seasons ago, Mr and Mrs McLaren went to Europe and followed Bruce around the championship circuit. “We had a wonderful time—the racing fraternity accepted us as one of themselves, and looked after us wonderfully,” said Mrs McLaren.

During the races in New Zealand Mrs McLaren acts as lap scorer, but this was Mr McLaren’s job on the European tour. Mrs McLaren’s job was to stand by with wet towels and warm pullovers.

With the wives of drivers and team managers, she would go shopping and sightseeing in the towns of Europe. “Usually someone in the party would speak the language, which helped a lot,” she said.

Language difficulties often caused panics on the racing circuits. “The turns of phrase were often confusing in the commentaries, and often we could only pick out the names. Once we heard ‘McLaren, wheel of Cooper’—we had visions of all sorts of accidents, but they only meant that he was driving the Cooper,” she said.

Brabham’s Crash

When Jack Brabham crashed in Portugal, Mrs McLaren was with his wife Betty in the pits. “It was dreadful—it was only half-way through the race, and we had to wait till the end of the 72 laps to get across the track to find out whether he was all right.”

And the end they dashed across the track, jumped into Bruce’s car and to the hospital, where they found after much difficulty and confusion that Brabham was not hurt, but was being kept under observation.

On another occasion in France, when the temperature was 96 degrees in the shade, and 136 degrees on the race track, Bruce came into the pits after the race badly cut with flying stones.

Now Mr and Mrs McLaren wait through the year for the few crowded weeks when Bruce is home. “It makes up for all the time he is away,” said Mrs McLaren. The house is always full of drivers and friends, and is besieged by young autograph hunters.

“It’s very hectic, but very exciting. I wouldn’t miss it for anything,” said Mrs McLaren of her life as mother of a racing car driver.

Women’s Lives in 1960s New Zealand

New Zealand social mores were clear when I was growing up in the 1940s and ‘50s: a woman’s place was in the home, taking care of husband and children. A few women (like my mother-in-law) worked after they had children, but the job options were few.

The staff at Christchurch’s The Press newspaper was overwhelmingly male. When I started in 1960, there was only one other woman reporter, besides myself, in the general reporting pool. A vacancy occurred in the Women’s Department, secluded in a separate little office down the hall. The other woman reporter, older and wiser about gender issues, adamantly refused to take it. I didn’t want to go either. I was having a ball scouring the big city hotels for interesting overseas visitors, interviewing artists, musicians and others with fascinating careers and histories. But I was not given a choice. Fortunately the women’s page editor, Tui Thomas, was sympathetic to my lack of interest in fashion and the social scene, and set me to reporting on meetings of various organizations focused on women and families.

I cringed when I first re-read this clipping from my scrapbook, with its sexist stereotypes. Looking more carefully, I sense the speaker’s unease. By the early 1960s, change was in the air. I don’t remember who Mrs Holmes was, but I imagine her as an older woman struggling to reconcile traditional values with the emerging demand by a younger generation of women for an expanded role in the world outside the home. I’ve appended a transcription, in case you have trouble reading the old newsprint.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The Press, March 28, 1961 (transcription)

Importance of Maintaining a Balance in Family Life

“Do we find ourselves so engrossed in outside-the-home activities that we only think of our husband’s meals and his clean socks?”

This question was put to women members of the Christchurch Parents’ Centre last evening by Mrs Helen Holmes in a talk on “Man-Woman Relationships in Family Living.”

Mrs Holmes warned of the pitfalls facing the housewife with too many interests apart from her family, and emphasized the importance of maintaining an even balance in her enthusiasm for interesting activities and her role as a wife and mother.

“In New Zealand today the woman does seem to be the focal point of the family,” said Mrs Holmes. “The man has to a certain extent lost his aloof position as head and dictator to the family. In some cases he is not even the sole provider—the breadwinner. The pattern of family life has changed vastly, and out of the pattern arises all sorts of complicated factors that have to be taken into account if we are to see ourselves as we are.”

The list of a woman’s activities in and outside the home was a formidable one, often including home decorating, gardening, sport, a part in community affairs, reading and entertaining.

“When do we spend time with our husbands?” asked Mrs Homes. “With the woman rushing madly at six things at once and the man working hard at his job and being a general handyman at home, when have either of them the time to contemplate the situation and enjoy each other’s company?”

Mrs Holmes said that a woman must be able to remain feminine—as she was when her husband married her. “A woman is first a wife and partner to her husband. A husband must be able to find peace and relaxation in his home, though providing an atmosphere of peace can be a full-time job for a woman.”

For a woman, life was full of opportunities and all of them interesting. But she would need a good deal of physical, mental and emotional stamina to pursue them all. This applied also to all the things a woman had to decide for herself, by herself, decisions which could bring feelings of insecurity and uncertainty.

In this situation, it was sometimes hard for the woman to accept her dependence on her husband, and might be the cause of a lot of her difficulties. It was hard for her to strike the balance between her natural dependence and her new-found independence.

“We must remember that our husbands have this independence too,” said Mrs Holmes. “There will be many who don’t wish to be involved with feeding time and nappy changing, no matter what the books might say. We must realize this and respect it. There will be many husbands who resent the interests a woman may wish to pursue outside her home. there may be many wives who find themselves frustrated at the prospect of so many interesting things to do and so little time and energy to spare for them.

“There are so many pitfalls. The man is no longer the single-minded dictator, sure of his authority, the woman is no longer his willing servant who only employs roundabout methods for getting her own way, the children are no longer seen and not heard. The role and status of each member of the family are no longer clearly defined and accepted.

I am thankful

I am thankful today for my new refrigerator. Our old one died a few weeks ago. Its replacement, a New Zealand-made Fisher & Paykel, was delayed by labor problems at the Los Angeles docks and eventually had to be unloaded in Vancouver and trucked down to Mendocino. Meanwhile Canclini’s, our local appliance dealer, gave us a smallish loaner, which has been parked out in the garage. We have gotten used to traipsing back and forth carrying milk or butter, and had set up ice chests on the back porch in preparation for an overflow of drinks and produce to feed our visiting family and friends during the Thanksgiving holiday.

It would be inconvenient, but we would cope. We’ve survived worse holiday crises. There was that time thirty-five years ago when we were remodeling an old house in Palo Alto. The kitchen walls were stripped down to the studs. Crates of new kitchen cabinets filled the living room, blocking access to the fireplace. I noted in my journal: At least I did warn [our friend] Judi that we might be picnicking amongst the mess. … [Our teenage sons] moved the kitchen cabinets today so that the sitting room & fireplace are usable again. Until the gas lines are reorganized, we have no heat, and the weather is getting colder, so it was important to be able to have a fire in the fireplace. We have plenty of firewood at least. On 11-30-1979 I noted that we had a delightful ‘old-fashioned’ Thanksgiving with Judi and her son Mark, who had been friends with our sons since they were little boys.

Thanksgiving a year later, the second floor completely rebuilt, we were waiting for the new roof to be completed and keeping a wary eye on the weather.

Journal 11-24-1980: The disaster finally happened over the weekend – eight weeks good luck couldn’t last. It rained Friday evening. Trusting in the plywood sheathing, we didn’t cover the floor with plastic all that thoroughly – a mistake. Throughout the night new drips opened up in the ceiling, mainly in the places where old plaster joined with new or at best was sagging or cracked. Buckets and towels all over the floor. We had to move out our bed because of a drip above us, which turned into a downpour slightly further along the crack about 3:00 am. David’s room also, where old gable met new roof, had a line of drips. Nasty watermark on the ceiling (most of which we were going to redo anyway). No permanent damage to floor. Spent all Sat. cleaning up in preparation for Thanksgiving, which I suspect is going to be as improvised as it was last year, though in different ways. Kitchen is finished, though with temporary lighting (as is all of ground floor). Can’t use the fireplace – need extension flue, which is still being built. Will have to decorate at eye level, prevent people’s eyes from moving upward, because of water marks on ceiling and upper walls. Stairwell still a mess of lath and ladders.

We survived that Thanksgiving holiday too. But this year we had a last-minute rescue. The kind men from Canclini’s brought us the new fridge on Wednesday morning and also left us the loaner until after the weekend, just in case we needed extra space. The turkey sits there now. In a little while, I’ll head out to the garage one more time and bring it in to the oven.

Thank you, Canclini TV & Appliances, and Happy Thanksgiving everyone.

Going Dark

In 1966, my friend Diana Neutze developed multiple sclerosis (MS). She was not yet thirty years old.

I first met Diana about ten years before this, when we shared English Lit. classes as freshmen at Canterbury University in Christchurch, New Zealand. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. I was part of her wedding, and she of mine. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate mothers of small children in London. Even after I moved to California and she returned to New Zealand, we stayed in touch as best we could.

For decades Diana’s illness came and went. She learned to live with it, devising ingenious stratagems for making sure she stayed mobile and independent. Whenever possible, she refused medications. All she had left, she said, was her mind, and her ability to find joy in music and the beauty of her garden. Painkillers took that clarity of mind from her, and this she could not allow. Right up until the end she was writing and publishing poetry. (I reviewed a recent book in these pages) I introduced her, via email, to a quadriplegic friend who got her started with voice recognition software. When she could no longer edit using one finger on a keyboard, or see to read, she dictated edits to a carer.

Diana and I traded poems and, as her body slowly but inexorably closed down, thoughts about death. She was in my mind when Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino invited local poets to respond to Wendell Berry’s poem “Going Dark” at a 2012 Winter Solstice event. I sent the poem to Diana, and included it in my new chapbook, Earthward. When I spoke to Diana via Skype in April 2013, three days before she died, she accepted my promise to dedicate Earthward, to her memory. At her request, my poem, “Going Dark,” was read at her funeral. Here it is:

Going Dark

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

— Wendell Berry

My friend’s body is a brown leaf,

shriveled and curled inward.

Pain is a constant, yet

the fierce flame of her will

refuses surrender.

It’s not death’s darkness she resists

but the loss of a self transfixed

by what is beautiful:

a Bach air, the light

through her walnut tree.

This dark she speaks of

has no scent of earth,

no draft from unseen wings,

no sudden rustle in the undergrowth.

What can I say to her, and to myself,

this season of gathering in

our lives against the rainy dark,

against the ancient fear

that light will not return?

Just this: a dry leaf

fallen to ground disintegrates,

becomes the food that nourishes

all that sweetly blooms and sings.

My chapbook Earthward is available from Finishing Line Press. The direct link is: https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

Some of Diana Neutze’s poems can be read on her blog site, Living With Multiple Sclerosis.

The Doll

As a child, I was a trial to my mother. Throw epithets at me and I’ll own them: mean, resentful, difficult. I was jealous of my sister Evelyn, one year older than me. She was the beautiful one, with the blue eyes and golden ringlets my mother adored, the one with the heirloom china doll with its own blue eyes and golden hair, handed down from some relative or other.

Another word: ungrateful. That describes me this week, when an email from my youngest sister Alison arrived. She and my other sister, Patricia, had been doing a spot of spring-cleaning and had found my childhood doll. Did I want it? No, I replied, flooded with guilt about that unloved “child.”

A memory. I am maybe five or six. I am lying on my parents’ bed, sobbing and sobbing. I have been put there on time out for fighting with my cousin. Lee was a few months younger than me. She was then an only child, with parents who doted on her. Lee had a fancy new baby doll. Evelyn had the exquisite china doll. We played mothers and babies, but all I had for a baby was a yellow knitted creature of indeterminate parentage. I picked a fight. Lee and I came to blows. Time out. I sobbed at being hauled in from play, at the unfairness of life.

The door opens and Lee creeps in.

“What do you want?” Surly, still angry.

“I know a secret. You’re not supposed to know. Your Dad’s fixing Sally.” Sally was another heirloom, a celluloid baby doll so fragile she was constantly on Dad’s workbench with a broken limb.

An adult arm reaches through the half-open door and drags Lee out. It gives me satisfaction to hear her being slapped and scolded. A few minutes later my mother appears. “You might was well come out, then. It was supposed to be a surprise.”

Dad’s repair to Sally lasts no longer than usual. But at least I have a glimmer that someone cares. For my birthday I receive a large package from my parents. It is a doll who can close her eyes in sleep. But not a beautiful doll. She looks like me: straight dark hair cut into bangs like mine, brown eyes, a tiny mouth, her features molded in some coarse composition material. I play with her, of course, but do not cherish her.

Seventy years later, the doll’s portrait shows up in my email in-box. Where on earth has she been all these years, I ask my sisters. It turns out they found her among the effects of our eldest sister, Evelyn, who died several years ago. Had Evelyn kept her safe all these years? Or had she rescued her from our mother’s cluttered house when she helped move Mum into an assisted living apartment? We’ll never know. But it humbles me to think that both of them cared enough to keep the doll safe when her oblivious “mother” abandoned her.

The doll is now officially an antique, sister Pat tells me. She’s somewhat the worse for wear. Her hair is gone. It looks like she’s fallen on her face a few times. I feel a rush of tenderness for the forlorn creature she has become. I’ve asked my sisters to find her a good home.

Given Time

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

To offer a flavor of the book, I can’t do better than to quote the blurb by Fithian Press, the book’s publisher: “The book deals honestly with the process of dying, an ordeal shared by both of them. It also deals with the process of staying alive and in love until the ordeal is over… [Bigelow] writes with brutal honesty about her anger and grief over what has become of her husband and herself. The book isn’t a manual about how to take care of a dying man, but it makes the reader well aware of what a grueling job it is. “So this is it,” she writes. ‘This chemo routine is the rest of our lives together…and goddamn it, it’s going to be as good for both of us as I can make it.’ ”

Reading this book set me to thinking about my husband’s and my circle of friends. We’re all of an age where we’re facing mortality, both our own and our partners’. Physical infirmities creep up on us. Memories start to fail. The mechanisms of the heart become clogged. I know we’ll all do what we have to do, to the best of our abilities, when loved ones need our care, and that, if we are the ones whose lives are ending, we hope to have someone as caring as Helen to tend our passage. I’m grateful that services such as hospice are available. Most of all, I am inspired by Helen’s love of beauty to seek it out in my own life. Whether my time is counted in decades or years or even months, I want every day to be touched by grace.

At Gallipoli

The Anzac Day memory floats up from my childhood: gray dawn in a small New Zealand town, plod and shuffle of marching feet, old men in uniforms button-stretched across their chests. The oldest of the veterans lays a wreath at the foot of a cenotaph where names are inscribed: casualties of the First World War.

When the war started in 1914, New Zealand was a British colony of less than a million people. Eager to come to the aid of the mother country in her time of need, more than 100,000 men signed up, and well over half of these were killed or wounded. A place name that crops up often on the marble tablets of small New Zealand towns is Gallipoli, Turkey. Seeking to take Constantinople, Winston Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty, sent the Australia and New Zealand Expeditionary Force (the ANZACs) to storm the Gallipoli Peninsula, which overlooks the Dardanelles, a channel connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. Writing in Slate, journalist Andrew Curry comments: “Though Gallipoli was a small conflict compared with landmark battles of the first world war like the Somme, the battle for the narrow peninsula contains the story of the war in microcosm: the fatal bravado, the futile fighting, the error-prone assumptions made by politicians and generals, and the killing fields that decimated a generation of young men.”

At dawn on April 25, 1915, the ANZACs landed at a small cove surrounded by steep cliffs. They met stiff resistance from Turkish troops. For nearly nine months the two sides fought and died, until finally the ANZACs withdrew. The website for the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage comments: “It may have led to a military defeat, but for many New Zealanders then and since, the Gallipoli landings meant the beginning of something else – a feeling that New Zealand had a role as a distinct nation, even as it fought on the other side of the world in the name of the British Empire.”

The rugged landscape of the peninsula is now a Turkish national park, filled with cemeteries and monuments to the dead of both sides. I was there last week, almost ninety-nine years after that tragic venture. At every memorial site, huge semi-circles of temporary bleachers were being set up for the Anzac Day ceremonies, which will be attended on April 25 by tens of thousands of Turks, Australians and New Zealanders.

With us also at Gallipoli last week was a group of New Zealand high school students. We had met them the previous day in Troy where, in the shadow of a modern Trojan Horse sculpture, and with “ancient Greek” costumes rented from a nearby stall, they were having an exuberantly good time re-enacting battle scenes from Homer’s Iliad.

This day at Anzac Cove the mood was markedly different. With solemn steps the students inspected the graves, where the ages of the dead were little different from their own: seventeen, eighteen, twenty-four. One young man passed out red lapel poppies to visitors, including our American tour group. We watched as one by one the students approached the cenotaph, placed their poppy at its base, and stood a moment with bowed head.

A New Zealander by birth, I have not lived in my home country for fifty years. Nevertheless, that day of pilgrimage I carried with me a small New Zealand flag. Following the students’ example, I attached my poppy to the flag and placed them both in the drift of red poppy emblems that lay like fallen petals at the cenotaph’s base. I thought of the stories from Gallipoli of Turkish and ANZAC soldiers who bombed each other by day and in the evening shared cigarettes and rations and helped tend each other’s wounded. I thought of the kindness of our Turkish tour guide who reorganized the tour schedule so that my husband and I could visit the New Zealand memorial site. I thought of the words of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who led the Turkish troops, and later went on to become the founder of the Turkish Republic. They are engraved in stone at Gallipoli:

Those heroes that shed their blood

And lost their lives.

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country.

Therefore, rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies

And the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side

Here in this country of ours,

You, the mothers,

Who sent their sons from far away countries

Wipe away your tears,

Your sons are now lying in our bosom

And are in peace

After having lost their lives on this land they have

Become our sons as well.

Mousebags

For the third time since we moved to the Mendocino Coast, we’ve had an expensive car repair caused in part by mice chewing on the electrical cables. Time for another garage clean-up, and time to get serious about deterring the little darlings. We hied ourselves down to Mendocino Hardware to check out our options. Mousetraps? No. The field mice have a right to live, just not inside the building. Tony spied a gizmo that emits an ultrasonic squeal, which they’re supposed to not like. I was dubious; ultrasonic stakes installed in the vegetable garden a while back had no effect whatsoever on the gophers and voles. I picked up a can of something called Nature’s Defense. Organic, the label said. I scanned the ingredient list. Garlic, cinnamon, clove, white pepper, rosemary, thyme, peppermint. Hmmm! Interesting combination of smells. We decided it was worth a try.

On opening the can, we discovered that the smelly material was in granules that tended to clump together. The next challenge was how to contain it under the hood. I remembered that when I was a child, a favorite gift to sew for my grandma was a lavender bag. While the clipped lavender dried in the shed, I would rummage through my mother’s box of fabric scraps, drawing pieces of voile and dimity through my fingers, feeling their softness, hearing their colors sing to each other. I would stitch my neatest stitches to make a tiny bag, decorated with fragments of lace and a ribbon to draw in the top.

I figured the mice wouldn’t appreciate dimity and lace. But there was an old undershirt of Tony’s in the rag bag. I pulled out my sewing basket, threaded a needle, and set to work. Memories came flooding back as I sewed.

Filled and tied with string, the little bags are now fastened with duct tape around the engine. The car smells a bit garlicky, especially when we switch on the fan, so we’re trying to remember not to. It’s too early to tell how effective the repellant will be. I’ll let you know in a few months.