Archive for the ‘immigration’ Category

The way we see ourselves (and others)

Some years ago, when I was still in the workforce, I was rebuked at a performance evaluation for “not putting [myself] forward enough.” Startled, I explained to my boss that in the New Zealand culture in which I grew up, to boast about one’s accomplishments was considered very bad form. Modesty, on the other hand, was praiseworthy. I still think this is true. But I’ve come to realize that New Zealanders had, and probably still have, a contradictory notion: a self-perception of being more self-reliant, more able to come up with creative solutions to problems than people of other nations, such as Americans. This trait, we told ourselves, arose from necessity. Lacking an industrial base, and being so far away from industrial centers, New Zealanders had to import manufactured goods at high cost or make do and mend what we had. Everyone I knew grew their own vegetables. Women sewed and knitted. Car owners kept their vehicles for as long as possible. Frugality was a virtue.

I saw evidence of this sense of superiority to Americans in an exchange of letters with my mother in the early 1970s. I told my parents about a landscaping project Tony and I were working on at the house we’d recently purchased:

April 12, 1971

We turned bricklayers this weekend, and have now laid half of the front courtyard in red brick, basket weave pattern. It is looking beautiful—we are really very proud of ourselves, and it wasn’t as difficult as we expected. We used a dry mortar method, laying a base of sand mixed with cement, and tamping in a richer cement/sand mixture between the bricks. The most tedious part was washing off each brick and smoothing the mortar with a fine spray of water. Then twelve hours later you just slosh the lot down really thoroughly and leave it to set. Needless to say, we are both very fit these days. Apart from a patch of sunburn on my shoulders, I am feeling no ill effects at all today.

In her next letter, Mum must have made some comment on how impressive we must appear to our neighbors, doing all this work ourselves. And how typical of New Zealanders. I responded:

May 2, 1971

New Zealanders don’t have the monopoly on do-it-yourself, you know! You should see the crowds at the handyman-type shops every weekend here.

I continued with an anecdote that shed a less than favorable light on the prejudices of some other Kiwi immigrants:

We were a little amused at another N.Z. couple we know, who have this thing about N.Z. characteristics. We had invited them to dinner, & I tried to give [our friend] directions—after all, Cupertino’s house numbering system is completely random, & I thought they might at least want to know what freeway exit to take. But she pooh-poohed the whole thing—it was “terribly American” to give directions—if they couldn’t find their way by map they weren’t self-respecting N.Zers! As it turned out, they had (inefficiently) double-booked on engagements, & couldn’t come …

Reading this exchange again after so many years, I recognize the beginnings of a shift in allegiance. I was no longer blindly loyal to the sometimes insular attitudes of my birth country. I was learning to question assumptions and beliefs about any group of people. I was learning that being an immigrant is complicated.

The citizenship decision

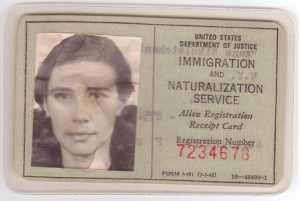

In 1972, five years after I emigrated to the US clutching my hard-won Green Card, my official status was Resident Alien. I was required to register at the Post Office every January. If I wanted to leave the country, I had to prove that my income tax payments were up to date. I had to remain “of good moral character” and could be expelled if I had a run-in with the law. And I couldn’t vote.

Meanwhile, opposition to US involvement in Viet Nam was heating up. A turning point for me was the May 1970 killing and wounding of students by members of the National Guard at Kent State University, where students were protesting the secret bombing of Cambodia. As a history major, I already understood why interference in another country’s self-determination was bound to end badly. It was obvious to me as an outsider that the Viet Nam War was a disaster. Yet here in this supposed Land of the Free, it seemed that the authorities were beating up people who said so.

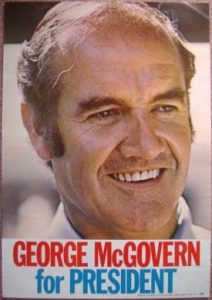

If I couldn’t publicly protest, and I couldn’t vote, at least I could help behind the scenes. I became interested in the anti-war policies of presidential candidate George McGovern, and began to volunteer in his California primary campaign. Here’s how I described my activities in a letter to parents:

June 2, 1972

I have been sticking my neck out in other directions lately too – have become very involved in George McGovern’s presidential campaign. I have put in some time at the campaign headquarters, and then got nailed to organise the local precinct. It is really rather fun, once I got over the initial panic. Support for him is very strong in this area, so I was lucky in the number of people I could con into working for me. Our house is going to be the headquarters for all 30 Cupertino precincts Tuesday (election day), so that should be interesting too. Am meeting all sorts of interesting people, especially the out-of-state students who are travelling around working for him. There are some neat kids amongst them.

McGovern won the nomination, but lost the November election to incumbent Richard Nixon. Meanwhile, I was feeling ambivalent about my own status. After five years in the US, a Resident Alien may commence the application process to become a citizen. Was I ready to do that? Could I turn my back on the land that had nurtured me and my ancestors? Could I pledge allegiance to a country whose foreign incursions I could not support? On the other hand, how badly did I want to share with my neighbors in making decisions about this place we all now called home? For most immigrants, this is a decision that requires careful thought and soul-searching. In the end, my husband and I decided to apply for citizenship. We didn’t know then how many years, frustrations and phone-calls it would take. But that’s another story.

Why we travel

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

Summer of 1967: an immigrant’s view

San Francisco, 1967. Sunday afternoon at Maritime Park. About twenty young black men sit on a low sea wall, bongo drums between their knees, thrumming an intoxicating rhythm. A crowd has gathered. Picnicking on the beach, my husband, children and I listen too, enthralled by the joyous sound. We have spent the morning exploring the old ships at the Hyde Street pier. Later in the day we explore the new tourist attraction of Ghiradelli Square.

In a letter to parents I wrote: … an old chocolate factory now converted into an arty plaza and shopping centre with fountains, outdoor restaurants, etc. … One of the most interesting places was the Children’s Art Centre – just a little gallery for exhibitions of children’s paintings, and free paper and crayons for any infant who felt like drifting in and drawing a bit.

New to California, we had heard of the hippies in the Haight/Ashbury district, so on our way home to Cupertino we detoured along Haight Street. Sure enough, we passed storefronts with funky signage, long-skirted young women with hair held by braided headbands, long-haired and bearded young men in tie-dyed tee-shirts, a group playing music on a corner. Like travelers viewing exotic fauna, we gawked and drove on.

It is only now, looking back, I realize how little we understood of what we were seeing. The flower children who poured into San Francisco in what is now known as the Summer of Love were an eclectic group, revolutionary in their rejection of consumerist values, opposition to the Vietnam war, and embrace of free love, drugs, art and music. But this counterculture had a historical context, and this as immigrants we did not possess. I remember where I was when I learned in 1963 that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Like my English neighbors, I was shocked. But I did not experience that communal sharing of grief my American contemporaries remember. On British television I saw newsreel images of civil rights marchers being attacked by snarling dogs, fire hoses, and baton-wielding cops. But that was in some barbaric, far-off country. From the BBC news reports about Vietnam, it was obvious that American military involvement was a disaster, bound to fail as the French had before them. I’d not yet grasped the deadly impact of the draft on young American men.

Over the decades that followed our first summer in the US, I gradually filled in my knowledge gaps, mainly through snippets of personal information: a teacher who dodged the draft by moving to Canada, a veteran who came back from the war physically and psychologically maimed, a man who as a student registered voters in the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, a doctor and his poet wife who were cast out of their New England village because of their opposition to the Vietnam war. I took part in fair housing studies, and learned first-hand the effects of racism. I read histories of the period. But there has always been for me a sense of distance, a sense of being an outsider when my contemporaries discuss the experiences of their youth. I believe this sense of distance is true of all immigrants who come to this country as adults. Try as we might to ‘become Americans,’ we simply cannot share in the memory of those collective experiences that have shaped the early lives of our American-born neighbors and friends.

However, it has been fifty years since our arrival as new immigrants, since that summer of 1967. Over the years, new national crises and issues have unfolded. We have reacted to them, talked about them with friends, shared in community actions. We learned to belong. We too have finally become part of the American story.

Immigrant arrival

According to archived weather records, the afternoon temperature at San Francisco Airport on Saturday May 20, 1967 hovered around seventy degrees. Fog had rolled in the previous night, but the mid-afternoon sky was clear, with visibility ten miles. As the British Airways plane dropped lower and lower over the waters of the bay, the surrounding hills became visible. Something about the quality of the light triggered a thought in my mind: this is the landscape of home.

It wasn’t the place where I grew up. Tauranga, New Zealand, is 6,500 miles southwest across the Pacific from California. But Tauranga’s distance from the equator, latitude 38 ? S, is the same as San Francisco’s to the north. The view from the air of San Francisco Bay and surrounding hills has similarities with Tauranga Harbour. Tauranga’s climate is subtropical and humid; it’s a rare day with no cloud in the sky. Even in the San Francisco Bay Area’s Mediterranean climate, with its clear summer skies, the ever-present offshore fogbank spreads a blue mistiness over the hills.

Part of the triggered thought was relief at finally coming back to terra firma. It had been a long flight, twelve hours over the pole from London. The journey had been made as comfortable as possible. The Silicon Valley company hiring my husband Tony had paid for first class tickets. The airline put us right up front, where there was plenty of legroom, and wall space to hook up a crib for our 18-month-old baby, who slept most of the way, sitting up occasionally to exclaim, “Airp’ane! Airp’ane!” The food was excellent, according to Tony. Our four-year-old son and I didn’t want to know. The two of us huddled together, miserable with airsickness.

Sight of the San Francisco Bay also signified something deeper: a recognition that this journey was the start of a new life. We were no longer in England, where the class system had us labeled as “colonials” and therefore outsiders. We were not heading back to our birth country, where the old baggage of family relationships and kiwi social assumptions would reassert their weight. We were free to find our own place in the rapidly growing, multi-cultural landscape of the exciting new high tech industry.

When we moved to England, we were unclear about how long we planned to stay. We stored boxes of belongings in New Zealand, as if we planned to return, and our mindset while we lived in England was that of visitor rather than permanent resident.

This move was different. We were immigrants, Resident Aliens in the terminology of our green cards. I knew there would be culture shock. I had experienced this phenomenon, unexpectedly, our first months in England. I had to drop all the slang I had grown up with, and was unsure how to correctly use English colloquial expressions. (Did to “go up to Oxford” mean to take the train from London or to attend the university? If the former, did one “go up” to other universities too?) This time I knew to expect that attitudes, ways of talking, and subtle social cues would be unfamiliar. Like caterpillars metamorphosing into butterflies, we would slowly take on the coloration of our new country.

Trudging through bureaucratic thickets: a visa saga

Having lived through the experience of applying for a United States immigrant visa, my heart goes out to those who recently trudged through the bureaucratic thickets, only to be turned away at airport gates by Trump’s anti-immigration order.

Having lived through the experience of applying for a United States immigrant visa, my heart goes out to those who recently trudged through the bureaucratic thickets, only to be turned away at airport gates by Trump’s anti-immigration order.

Every immigrant’s story is different, of course. But maybe telling our story, as documented by my letters to parents during that time, will offer some insight into the process which, even in 1966-67, and even with a US company going to bat for us, was exhausting and nerve-wracking.

Born in New Zealand, we were living in England, where my husband Tony designed and tested disk drives for the rapidly-growing computer industry. He interacted with people from US companies, several of whom had shown interest in offering him a position in the US, where skilled high tech workers were in short supply.

9 Aug. 66

p.s. Have you got my B.A. or M.A. certificate? If so, would you please send them airmail.

A complication was that when we left New Zealand in 1962, we boxed up belongings we didn’t think we needed to take and left them in a friend’s basement. Those friends sold their house and moved, sending the boxes to Tony’s mother, who sold her house and moved, sending them to my parents, who sold … By this time they were (we hoped) with my sister, Evelyn.

A complication was that when we left New Zealand in 1962, we boxed up belongings we didn’t think we needed to take and left them in a friend’s basement. Those friends sold their house and moved, sending the boxes to Tony’s mother, who sold her house and moved, sending them to my parents, who sold … By this time they were (we hoped) with my sister, Evelyn.

22 Aug. 66

Don’t bother any more about the degrees. …we are going to rely on a statement from the university registrar instead. It is for American visa – we need proof of special qualifications etc. to get onto special entry list. However, there is no hurry as yet, as American job is still a mirage on the horizon – needless to say we are both a bit edgy with all this uncertainty.

An excellent job offer from a Silicon Valley company came through in early October, and we put our house on the market immediately.

An excellent job offer from a Silicon Valley company came through in early October, and we put our house on the market immediately.

17 Oct. 66

The property market is very depressed here at the moment … so we can only hope for the best.

We don’t expect to leave until after Christmas anyway. The visa will take quite a few weeks to come through, & Tony can’t give his month’s notice until he gets it.

… After so many months of waiting around, we are finding it hard to believe that it has actually happened.

31 Oct. 66

We had our first viewer for the house yesterday….

You may have heard that we have had a delay over visas – U.S. authorities have stuck over this question of Tony’s degree & they insist on the fancy bit of paper. I wrote to Evelyn last week, so hope she has managed to do something about looking for it. Could you find out how she is getting on? It is possible she may still be assuming that it is in a mailing tube – it ain’t necessarily so – it could be flat in an envelope – or anywhere. Another thought – has she got all our things, or has Mrs. L. still got some? It really is urgent that it be found.

Apart from these problems, things are going quite well. We had a note from the removal firm the other day asking when we wanted them to come in – it seems that everything will be packed for us, transported, & unpacked at the other end – unheard-of luxury!

Having gone through every box, Evelyn finally found the degree certificate in a box labeled “Dining-room stuff.” She registered the package and mailed it with first class air mail postage.

Having gone through every box, Evelyn finally found the degree certificate in a box labeled “Dining-room stuff.” She registered the package and mailed it with first class air mail postage.

12 Nov. 66

I suppose you will have heard of the latest little crisis – bloody N.Z. Post Office managed to send the degrees by ship, due to reach us about Christmas! However, it mightn’t be disastrous. B.Sc. sent by Mrs. L did arrive safely, & the firm are cabling the university to send a duplicate of the degree. But it has got to the stage where I am beginning to wonder how much else can go wrong before we actually leave.

15 Dec. 66

…[Have] had another difficult week – actually, I had been putting off writing until we got our affairs a bit straighter. Anyway – on Monday we learned that the visa petition had not yet been filed – they are still waiting for the M.Sc. degree. The ship was supposed to berth yesterday, but as the mails are already in chaos with the Christmas rush, heaven knows when it will turn up. So, having found out where the petition had got to, we thought we might as well check up on the time scale from the embassy. Here we got a horrible shock – we were cheerfully informed that it was going to take five months from the time the thing was filed in San Francisco – don’t ask me how they manage to stretch the red tape that far – that’s just what they said. Contracts half-way through being signed for sale of house – still legally possible to back out – just – but very inconvenient for everybody else, so we are going on with sale, & still negotiating a deferment of the completion date. Even so, we will probably have to find somewhere else to live for a while, which is going to be a bit of a problem. Tony very depressed at the thought of staying at [his current job] for another six months, still waiting to hear whether California are prepared to wait that long.

30 Dec. 66

How up-to-date are you with our plans? The degree has been sent to America, we haven’t heard yet whether it & its associated papers have been presented to the authorities, we have until the middle of April to get out of the house, & the name of someone in the American embassy whom it is possible (possibly) to push to get a visa sooner, and at present are gathering together all the documents (in triplicate) we require, such as birth certificates, marriage certificate, photographs, etc.

18 Feb. 67

I forgot to tell Evelyn that we have received a letter of apology from the Postmaster-General, though no compensation – didn’t really expect it!

Trying to get information about the status of our application proved almost impossible. Before 8:00 am, the phone at the US Embassy would ring and ring. From 8:00 am to 5:00 pm we’d get a busy signal. But finally, one day I got lucky.

Trying to get information about the status of our application proved almost impossible. Before 8:00 am, the phone at the US Embassy would ring and ring. From 8:00 am to 5:00 pm we’d get a busy signal. But finally, one day I got lucky.

28 Feb. 67

You’ll have to excuse me if my letters are a bit erratic in the next few weeks. We have to be out of the house in six weeks, and it is just possible that we may be leaving for America about then. The papers arrived from San Francisco last week. I don’t think I told you that we had the petition changed a few weeks ago, on the advice of the American consul in London. We had applied for 3rd preference – for those with degrees, etc., but the waiting list for this category goes back to last September for NZers – as there are only 100 immigrants a year total [from NZ] and 10% for this preference, this is not surprising. Anyway, he suggested trying for 6th preference – skilled workers not easily available in U.S., for which Tony, being an electronics engineer, would qualify, & for which there are places available now for NZers. So a frantic dash to London by me, to bring back yet another lot of forms to fill in. Can you remember all the addresses you’ve lived at since you were 16? …

15 Mar. 67

The petition has now gone for clearance to Wellington (checking up on our murky past). I don’t doubt there will be another delay, in which case we will have to move into a flat or something here. The estate agent who sold the house is looking for something for us, but I expect we shall have to pay through the nose for it.

We were lucky to find a furnished flat. On April 14 packers moved in and packed our household goods for shipment to California. We took with us only the clothes for ourselves and the two children (ages three and one) that would fit into suitcases weighing under the economy class limit, and borrowed a few items from friends, such as a cot and stroller for the baby.

We were lucky to find a furnished flat. On April 14 packers moved in and packed our household goods for shipment to California. We took with us only the clothes for ourselves and the two children (ages three and one) that would fit into suitcases weighing under the economy class limit, and borrowed a few items from friends, such as a cot and stroller for the baby.

15 April 67

… The clearances have now arrived… Now we only need a quota number from Washington, a medical check & formal interview, and that is the lot. At least we have this place until the end of May, which gives us a breathing space.

1 May 67

Believe it or not, we now have immigrants’ visa to the United States. We spent all day at the Embassy today. Having got up about 5:30 in order to be there by 8:30 as instructed, eight hours of sitting around – though I must give them credit for having things reasonably well organised, considering the numbers of people they had to get through. We were through the whole rigmarole by about three o’clock, & they offered to post the visas out to us instead of making us wait around with the kids for another couple of hours while they finished the processing – offer gratefully accepted. Actually, the kids were extremely good, considering David’s boundless energy & Simon’s lack of sleep. We were well stocked up with sweets & biscuits & story books, & of course there were plenty of other children to play with…

We are booked to leave England on Sat. 20th May, flying direct to San Francisco over the pole.

My letter of 18 May 67 speaks of farewell visits with many friends. At the last minute I learned that the company was flying us out first class, so I could have had more of the children’s gear with me for the last few weeks. But that was a minor irritation compared with the relief of having the ordeal over with, and gratitude that the Californian company kept the job open for Tony all those months. I wish all today’s visa-holding immigrants and visitors could have an equally happy ending to their story.

My letter of 18 May 67 speaks of farewell visits with many friends. At the last minute I learned that the company was flying us out first class, so I could have had more of the children’s gear with me for the last few weeks. But that was a minor irritation compared with the relief of having the ordeal over with, and gratitude that the Californian company kept the job open for Tony all those months. I wish all today’s visa-holding immigrants and visitors could have an equally happy ending to their story.

Fight or flight: an expatriate ponders

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

In this period of political unease in the US, when many have expressed a wish to go live somewhere else, I think back to our last few years in England in the mid-1960s, and how alienated we felt then.

An economics text for UK students cites several reasons for the dour mood of the country in those years. Author Tejvan Pettinger writes:

Despite higher economic growth, the UK performed relatively poorly compared to major competitors. UK productivity growth was relatively lower due to several factors. such as:

- Lack of willingness / ability to innovate

- Poor industrial relations with a growing number of days lost to strike action. Some argue this was exacerbated by Britain’s class system.

- Trade unions effectively blocked efforts at reform.

- Complacency.

- Lack of public sector infrastructure.

Even though we might have returned to New Zealand then, our lives did not take that turn. In my old black filing cabinet I found a letter to my parents that lays out the situation.

19 July 1966

… [W]e are still unsettled about what we are going to do with ourselves. We did have serious ideas of returning to New Zealand, but I am afraid that is now dropped through lack of interest on the part of N.Z. firms. We are feeling rather sour about the whole affair, especially as N.Z. is always griping about the country’s young brains staying away in their thousands. A year ago Tony made a private enquiry to I.C.T. (NZ) asking about the prospects of getting a job, and did not even get the courtesy of a reply. Then six months ago head office in London offered to arrange a transfer for him. After much prodding, official letters to N.Z. eventually got answered, but in such unsatisfactory terms that no-one knew quite what they wanted. It has taken six months for N.Z. to agree to take Tony, but they have made it plain that they consider he is being foisted on them by London, and that they are still suspicious of him. Their terms are that he is to have a year’s training in computer systems, and not until “they see how he gets on with the training” will they consider discussing position or salary. Since Tony is one of I.C.T.’s top authorities on computer tape, and already has a big general background in computer systems, he has taken this as a not-so-polite brush-off and told them what they can do with the job. If he were in his early twenties, without family, and determined to get back, it might have been different. But at his age—rising thirty is a critical age in his line of industry, since the job decisions he takes now will set the line his career is to take. So you see he just can’t afford to throw away yet another year on a job that might still not eventuate, and would probably be a frustrating backwater if it does. Other computer firms in N.Z. take much the same line—not interested enough to get him an interview in London, just “drop in when you get to N.Z. and we will see if there is anything doing.”

Meanwhile, he is still negotiating for a job with an American firm, which might mean going to live in California, but nothing has been settled yet, We feel it is time we got out of this country—the present economic crisis is just a symptom of a general decadence and backward-looking attitude, and we can’t see any future for Britain.

You mentioned your feelings towards Britain as a spiritual home—I can understand this, and think it is one of the main forces that pushes young people into coming over here. I think it is this thing about historical roots—it gives a wonderful sense of history and continuity to visit places that have been lived in for so long by so many different peoples. But it is necessary to distinguish between this feeling and the present political reality. Modern Britain doesn’t care two hoots about New Zealand—it is either confused with Australia (well, they are both on the other side of the world, what does it matter?) or else N.Z. is regarded as some sort of idealised paradise where it is never rainy or cold, and where they would like to go to escape from reality. As a political or economic entity it just doesn’t exist. And while N.Z.ers continue to believe that it doesn’t exist either, except as an offshoot of Britain, there is not much hope for its future, and the young brains will continue to stay away in their thousands.

Which makes us more or less permanent exiles, at least spiritually. But if we do go to America, it is probable that Tony will be earning enough money for us to afford the occasional holiday in N.Z. I feel very sad that the children do not yet know their grandparents, but that is one of the penalties of our decision. I hope you will understand.

Airline pilot: a loyal expat

Among the New Zealanders Abroad series I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper in the 1960s is a lengthy interview with airline pilot Captain Ronald Hartley. His celebrity in 1962 was as commander of the airliner taking Princess Margaret and the Earl of Snowdon to Jamaica for the independence celebrations. Later that decade he flew Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh to Canada.

Princess Margaret dancing with Sir Alexander Bustamente at the Jamaican Independence Day celebrations. From http://blogs.jamaicans.com/

A World War II Royal Air Force hero, Hartley helped form an airline that amalgamated with B.O.A.C. He was one of the first B.O.A.C. pilots to train on Britannia aircraft, and in 1962 was deputy flight manager of the Britannia 102 flight. Much of his work involved the planning of new aircraft, such as the Vickers VC10.

“We are surrounded by experts who know what is possible – it is our job to stand in the middle of the argument and tell them exactly what we require.” In such things as the layout of cockpits pilots can bring practical experience, and Captain Hartley and his colleagues are at present working for a standardization of cockpit design. This is so that a pilot can if necessary step into a strange place and know where all the instruments are likely to be on the panel.

Captain Hartley was born in Auckland in 1909. When he was 19 years old his parents returned to England, taking him with them. Although he never returned to New Zealand, Captain Hartley was still very proud of being a New Zealander.

“There is something about the land of one’s birth that makes you always loyal to her,” he said. He is proud of New Zealand’s social legislation, and the high reputation that New Zealanders have in England, a reputation gained, he thinks, from their service during the two world wars.

His memory of New Zealand is a picture of beaches and bush. “When I was a boy we used to jolt down a dirt road to the beach at Muriwai or Piha, and when we got there we would have the whole place to ourselves – not like the noisy, overcrowded holiday places here in England.” He remembers Boy Scout camps on the shores of Manakau Harbour, with the bush coming down to the water, and long hot summers with warm water for swimming. Now he has a cottage in Devon, but even in mid-summer the water could only be described as “bracing.”

He found the different way of life in England hard to get used to at first. “In my first year I rushed around joining clubs – tennis clubs, athletics clubs, anything to make friends.” He was conscious of the class distinctions in English society. ”It sometimes worried me that I didn’t know much about things like wines, or the right brand of cigars or caviar. Now that I am older, and know more about me, I have learned better.”

He had come to realize that most people needed his help and friendship more than he needed theirs, and he has worked on this assumption throughout his career.

“I have tried to bring up my children the same way too. When they showed signs of shyness at an early age, I used to tell them, if they were going to a party: “Now don’t you dare have a good time until you see some little boy or girl who looks lonely and make friends with him.”

For the new immigrant to England such as myself, his comments about not being able to return permanently to his birthplace were an uncomfortable revelation, and one we quickly discovered for ourselves. He was having too much fun, he said.

“I enjoy dealing with people, and I love the clash of personalities and opinions that you get in such a huge and complex organization as this.”

Postscript: on Nov. 21, 1969, Captain Hartley was killed when as a passenger on a Nigerian Airlines flight, the new Vickers VC10 crashed on its landing approach to Lagos airport.

Droplets in an immigrant wave

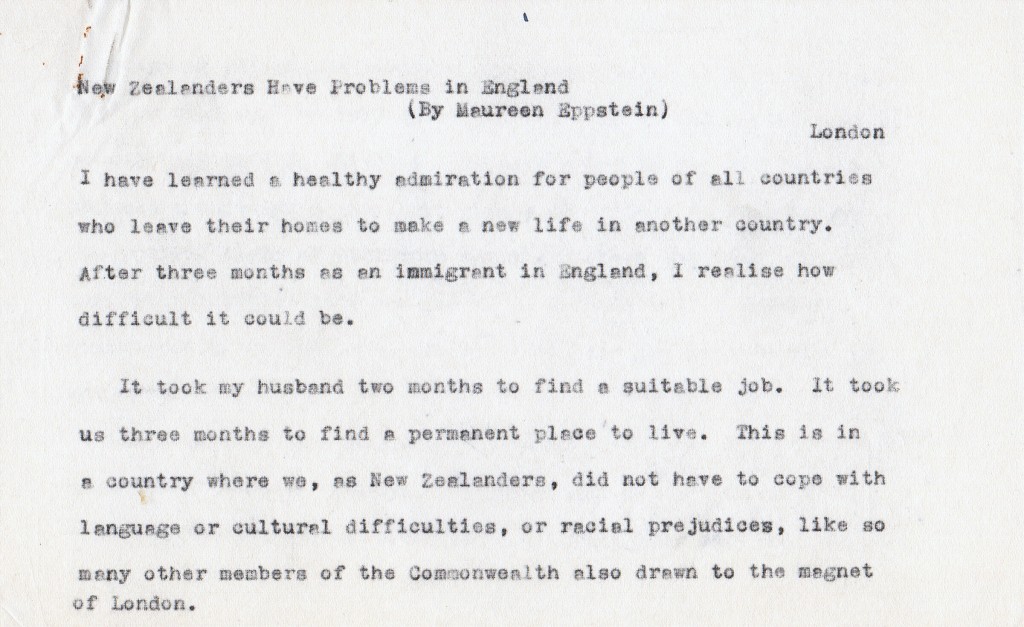

In a 1962 article I wrote for my old paper, the Christchurch (NZ) Press, a draft of which I found in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

I have learned a healthy admiration for people of all countries who leave their homes to make a new life in another country. After three months as an immigrant in England, I realize how difficult it could be.

It took my husband two months to find a suitable job. It took us three months to find a permanent place to live. This is in a country where we, as New Zealanders, did not have to cope with language or cultural difficulties, or racial prejudice, like so many other members of the Commonwealth also drawn to the magnet of London.

We had no idea at the time of the hugeness of the immigration wave in which we floundered. To aid in post-war reconstruction in the 1950s, Britain had recruited labor from its colonies, primarily the West Indies and the Indian sub-continent. At that time people from the Empire and Commonwealth had unhindered rights to enter Britain. However, by the late 1950s, with the British economy faltering, racial prejudice reared its violent head. The Conservative Party government proposed legislation to make immigration for non-white people harder. One aspect of the proposed bill was to deny entry to dependents of immigrant workers. Before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 could go into effect, the entry of dependents into Britain increased almost threefold as families attempted to beat the deadline. Total immigration from what was known as the New Commonwealth swelled from 21,550 in 1959 to 58,300 in 1960 and a record 125,000 in 1961.

Statistics are from Paul Foot, Immigration and Race in British Politics (Penguin, 1965)

All these people needed somewhere to live. It is no wonder then that rents soared and accommodations of any sort were snapped up. While Tony job-hunted, I haunted rental agencies for a short-term apartment (or flat, as they’re called in England) and, the hefty Bartholomews Atlas of Greater London under my arm, braved the Underground and navigated the suburbs. My letters to parents are full of observations like this one:

It’s amazing how so many of the little villages that have been absorbed into the city still retain their village atmosphere – you pop up from an Underground station and could imagine yourself miles out in the country – unless you happen to be on a bit of a rise, when you see nothing but houses as far as the eye can see. One place I visited, for instance, Muswell Hill, you had to go by bus through a very extensive patch of woodland to get to it. That place I didn’t take, incidentally, because the bath was in the kitchen – covered by a lift-up board and a little frilly curtain. When I mentioned this to another English landlady she didn’t even raise an eyebrow.

My letter continues:

We have now moved out of our hotel into a bedsitter out at Hampstead, for which we are being grossly overcharged – I guess we just took it in a moment of desperation.

The rent was six and a half guineas a week (the same buying power as about $200 in current U.S. dollars.) Every piece of furniture was shaky about the legs, and the cooking facilities were two gas rings crammed into a cupboard with about six inches of counter surface. The shared bathroom was down the shabby hall. I described the landlady as

a bit of a social type – she was too busy preparing for her cocktail party last night to attend to our wants, which brassed me off considerably. Still we get on quite well with her little dog, so with a little careful handling relations might improve.

Relations did not improve. Still vivid in my mind is one of our shouting matches. I had returned from the local laundrette with clothes still damp, in spite of multiple coin feeds to the drier, and had strung clothesline around the room. In walked Mrs. Ashley-Davis. “My furniture! My furniture!” she wailed, hand to her heart. Other disputes must have followed. In a letter to parents dated May 25, after giving the news that Tony had accepted a job near Windsor, I mention that we have given notice

…after some somewhat violent disputes with the landlady, in which I managed to lose my temper – catastrophe!

Finding permanent housing proved even more frustrating. I told my parents:

…for the last three or four days we have been footslogging, railriding, bussing, and generally getting fed up in a wide arc around the area…

We moved out to a hotel near Tony’s new job. My letters for the next few weeks are full of the false hopes and discouragements of the search. Finally we got lucky: a second floor flat in a Victorian brick semi-detached house just down the hill from Windsor Castle. A roof over our heads at last!

Here’s a modern Google Maps street view of the neighborhood. It still looks much the same.