Archive for the ‘Work’ Category

Technological breakthrough brings excitement

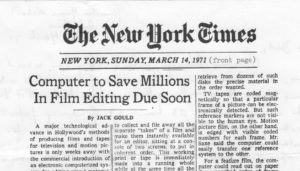

On March 29, 1971 I scrawled a letter to my parents on the back of a copied newspaper clipping. In it I wrote:

We thought you might be interested in this cutting from the New York Times. It was also reproduced in the local paper, as well as the major papers in Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles, and the phone hasn’t stopped ringing at CMX [the company where my husband Tony worked] ever since. They have been demonstrating to all the major movie & TV producers & advertising agencies – a fascinating assortment of characters around the place, Tony says. Tony is going to Denver, Colorado for a magnetics conference the week after Easter. I think he is feeling quite amused about confronting the magnetics “Establishment” who were convinced that what he did (using magnetic computer disks to record video pictures) was technically impossible.

The article, by Jack Gould, the New York Times’s television and radio critic and reporter, goes into more detail. “Computer to Save Millions in Film Editing Due Soon” is its title. Calling it “a major technological advance in Hollywood’s methods of producing films and tapes for television and motion pictures,” he wrote:

The article, by Jack Gould, the New York Times’s television and radio critic and reporter, goes into more detail. “Computer to Save Millions in Film Editing Due Soon” is its title. Calling it “a major technological advance in Hollywood’s methods of producing films and tapes for television and motion pictures,” he wrote:

“In layman’s terms, the heart of the CMX system is its ability to collect and file away all the separate “takes” of a film and make them instantly available for an editor, sitting at a console of two screens, to put in coherent order. This working print or tape is immediately made into a running whole while at the same time all the trims and cuts are preserved for later consideration.

“Operation of the system borders on the eerie. The console operator can order up whatever he wishes to see. He presses no buttons or pulls any switches. Rather, he uses a pencil light that directs the system to offer a choice of “menus,” i.e., whether he wants the system to record, play back or edit.

“If the director wants to see Scene 1 of Act 2, he presses his pencil light, actually a photoelectric cell, against those words on the face of the screen. Instantly there is a still picture denoting that the sequence is ready for study. The light is then pressed against the word “run” and the scene starts.

“With the same pencil light the operator can order the system to stop. He can thereupon order a new starting point and new ending. Thereafter he can review the edited scenes and, if he wishes, compare them with the original.”

CMX Systems was a joint venture between the Columbia Broadcasting System television network and Memorex Corp., the company that had brought us to California in 1967. According to Wikipedia, the company’s name stood for CBS, Memorex, and eXperimental. Tony and his colleagues shared a patent for their work, as well as the satisfaction of having contributed to a breakthrough in technology. The company was sold in 1974, and Tony returned to Memorex, where he continued to work on magnetic recording technologies.

Time Magazine on women, 1972

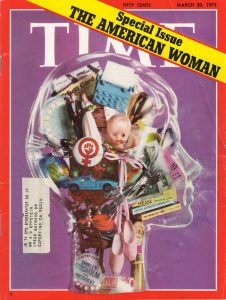

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

The issue starts, as usual, with letters to the editor. These are from female readers responding to the magazine’s invitation to “write to us about their experiences and attitudes as women, and to tell us how their views on this subject have changed in recent years.” I tabulate the responses. Twenty enthusiastic about the new feminism, three ambivalent, and six tending negative, arguing that, since very few higher level jobs are available to women, by going out to work they “trade the drudgery of housewifery for the drudgery of an office job.” Or, as another writer put it: “Rush out each day to that exhilarating, high-paid position; rush home to that hot-cooked supper (cooked by whom?); relax in that nice clean living room (cleaned by whom?). Most likely, dearie, you’ll hold down two jobs—‘cause when you get home from that executive job in the sky, there ain’t gonna be no unliberated woman left (and certainly no man) to do your grub work.” Sidebars titled “Situation Report” in the various sections of the issue reflect these caveats: prejudice is rampant against allowing women into higher paid or managerial professions.

Time’s editorial attempts to define “the New Feminism” as “… a state of mind that has raised serious questions about the way people live—about their families, homes, child rearing, jobs, governments and the nature of the sexes themselves. Or so it seems now. Some of those who have weathered the torrential fads of the last decade wonder if the New Woman’s movement may not be merely another sociological entertainment that will subside presently.”

Subsequent pages offer a history of the currents of social change that “have converged the make the New Feminism an idea whose time has come.” There are portraits of a range of American women, a piece on “the organizations, aims, difficulties and range of opinions that help make up Women’s Liberation in all its diverse forms,” a one-page snapshot of attitudes in Red Oak, a small Iowa town. Here’s a quote: “Many Red Oak women agree with Doctor’s Wife Jane Smith: ‘A woman’s place is in the home taking care of her children. If a woman gets bored with the housework, there are plenty of organizations she can join.’” A photograph shows Mrs. Smith entertaining friends at bridge. I have a flash of memory: one of my sisters saying the same words to me.

The “Politics” section of the magazine showcases some familiar names: Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, Martha Mitchell, and describes the bipartisan effort of the National Women’s Political Caucus to get more women elected, or selected, as delegates to the Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

The “Science” section describes the difficulties a woman astronomer faced. As a woman Margaret Burbidge, who helped develop a new explanation of how elements are formed in the stars, “found that she could get precious observing time at Mount Wilson Observatory only if her husband [a physicist] applied for it and she pretended to act as his assistant.” The Burbidges also ran into nepotism rules at the University of Chicago. “’The irony of such rules,’ says Mrs. Burbidge, who had to settled for an unsalaried appointment while her husband was named a fully paid associate professor, ‘is that they are always used against the wife.’” I think of women scientists I have known who suffered the same exclusion, such as Beatrice Tinsley, a British-born New Zealand astronomer and cosmologist whose research made fundamental contributions to the astronomical understanding of how galaxies evolve, grow and die. Beatrice had to divorce her husband, a Texas University professor, and move to Yale to gain the position she needed to do her work.

In many science fields, recognition for outstanding women is still abysmally low. I think of efforts by my son David, a mathematician, to redress the paucity of profiles of eminent women mathematicians in Wikipedia.

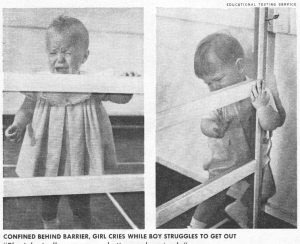

Section after section, the stories continue. “The Press” section is subtitled “Fight from Fluff,” how women’s pages are shifting to more general interest features. ”Modern Living” talks about efforts to find new pronouns, the opening of day care centers, and changes in marriage dynamics. The Situation Report for the “Law” section puts the number of women lawyers in the U.S. at 9000, 2.8% of the total number of lawyers. Of this small number, “less than 12% of them were making more than $20,000, as compared to 50% of the men.” Similarly depressing are statistics for recognition of women in the arts, in business, and in medicine. The “Behavior” section, which looks at research into sex-related differences in early childhood, seems to reinforce stereotypes: “Many researchers have found greater dependence and docility in very young girls, greater autonomy and activity in boys.” The accompanying pictures show two babies behind a barrier set up to separate them from their mothers. The little girl cries helplessly; the boy struggles to get out.

A keynote essay by Sue Kaufman, author of the novel Diary of a Mad Housewife, attempts to capture the feelings of a composite American woman, interested in the new ideas, admiring of feminist leaders, but cautious about jumping on the bandwagon. Kaufman describes an imagined scene: an admired leader is coming to town to speak. The woman arranges for a babysitter. “She will go, usually with friends. They will arrive … take their seats—and slowly it will begin to happen … she begins to feel the flickers and currents of a mass communion, a rising sense of excitement that she imagines parallels what one feels at a revival meeting … this powerful thing happening, this sweeping, surging, gathering-up-momentum feeling of intense camaraderie, solidarity movement.” After the meeting is over, Kaufman describes the woman driving home, paying the sitter, returning to the children and the kitchen “to take up the reins of her existence. Only—something is wrong. She is overwhelmed by a terrible sense of wrongness, of jarring inconsistency. There was that surging, powerful feeling in the hall, and now, stranded on the linoleum under the battery of fluorescent kitchen lights, there is this terrible sense of isolation, of walls closing in, of being trapped. …but she doesn’t burst into tears. …In spite of the desolation she feels, she knows that she is not alone…there is enormous comfort in knowing that. And knowing that is one of the big changes in her life.”

When programming was a women’s job

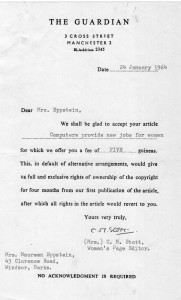

Back in the day when computer programming as a profession was so new it lacked a gender bias and could well have become a female specialty, I wrote an article about a woman programmer which helped launch a successful freelance business staffed almost entirely by stay-at-home mothers. For me too, it was a big breakthrough: the story was published by the Guardian newspaper on 31 Jan. 1964 under the headline “Computers provide new jobs for women.”

I first met Stephanie (Steve) Shirley in 1963, when our same-age babies were tiny. We had a pleasant chat about what intellectually stimulating work programming was. Frustrated with the sexism that prevailed in the world of employment, Steve had left her job with Computer Developments, Ltd., to start her own company, Freelance Programmers. Her workload was growing as new clients learned of her services, and she was starting to reach out to other former programmers for help.

In a letter to parents a week after the article was published, I wrote:

… My article was published in the Guardian, and since then I have had a flood of letters. Mainly for forwarding to the woman mentioned in it, a computer programmer, retired with a baby the same age as ours, who is trying to get other women like herself to join her in working on a free lance basis.

Less than a year after my first article, the Guardian published my follow-up. Freelance Programming Ltd. was launched. Over time it grew to 8,000 employees, and Dame Stephanie Shirley is now recognized as a pioneer of the British information technology industry. Here’s the follow-up article:

Computer women

In January of this year Mrs Steve Shirley was working quietly at home making up computer programmes in between caring for her baby and doing her housework. Now she has found herself the head of a company employing upward of twenty retired, home-bound programmers like herself. Like many businesses, it started in a very small way. When she retired from her job as a programmer with a big computer company, she was offered a few programming projects to keep her occupied at home. She could work at them in a leisurely fashion, enjoying the contrast between the stark, modern, technical world of computers and the idyllic charm of her cottage in the Chilterns. In this way she found a mental satisfaction that had not been fully achieved in caring for her home and family.

As her circle of clients widened, she was considering seeking out other retired programmers like herself who could help with the load of work. Then a Guardian article on programming as a career for women [my first article] brought in a flood of letters from women who were desperately needing something more stimulating to do with their time. Many were very highly qualified, but because of their children could not consider going back to a job that wanted them on an all-or-nothing basis.

There are some obvious difficulties in running a part-time business of this kind, and Freelance Programmers Ltd. is now having to face some of them. The first is one of organisation. To get a reasonable standard of efficiency, Mrs Shirley had to eliminate those applicants who did not have access to a telephone. The business is at present being run from the cottage, where the telephone rings at all hours of the day and night, and Mrs Shirley herself works very long hours keeping in touch with her staff. In order to get back herself to the part-time basis which would give her time for her family, she plans to open a central office. Here she would be able to employ a typist—at present she does the typing herself, or sends it out to one of her staff, thus making a two-day time lag. The office will be in an area where some of the staff are already living, and her plans are for a combined office and nursery suite, so that the mothers who come to the office will have the children cared for, but will be at hand if needed.

There will still be many of the staff working by themselves at home. Some of them are doing it because they need the money, but for the great majority it is a release from the pressure of four walls and a roof and a tedious round of housework. Mrs Shirley has proved that this method can be made to work, particularly for fairly short-term projects. A larger job, that might take perhaps two years to complete, she prefers to give to women less tied to family responsibilities.

She also needs more free women for the large amount of travelling and meeting clients involved in the business. An ideal staff member is a woman with no children, who is married to a schoolteacher. She had been unable to get a normal job because she wanted all the school holidays off to be with her husband, and not just the regulation three weeks. But for several months at a stretch she is free to go anywhere, do anything for the company.

It has become clear that an entirely homebound, part-time organisation will not work satisfactorily. But a group that is basically of this sort, with a leavening of more mobile staff and with an efficient central organisation, may well be a model on which similar groups of professionally trained women might be based.