Archive for the ‘housing’ Category

The way we see ourselves (and others)

Some years ago, when I was still in the workforce, I was rebuked at a performance evaluation for “not putting [myself] forward enough.” Startled, I explained to my boss that in the New Zealand culture in which I grew up, to boast about one’s accomplishments was considered very bad form. Modesty, on the other hand, was praiseworthy. I still think this is true. But I’ve come to realize that New Zealanders had, and probably still have, a contradictory notion: a self-perception of being more self-reliant, more able to come up with creative solutions to problems than people of other nations, such as Americans. This trait, we told ourselves, arose from necessity. Lacking an industrial base, and being so far away from industrial centers, New Zealanders had to import manufactured goods at high cost or make do and mend what we had. Everyone I knew grew their own vegetables. Women sewed and knitted. Car owners kept their vehicles for as long as possible. Frugality was a virtue.

I saw evidence of this sense of superiority to Americans in an exchange of letters with my mother in the early 1970s. I told my parents about a landscaping project Tony and I were working on at the house we’d recently purchased:

April 12, 1971

We turned bricklayers this weekend, and have now laid half of the front courtyard in red brick, basket weave pattern. It is looking beautiful—we are really very proud of ourselves, and it wasn’t as difficult as we expected. We used a dry mortar method, laying a base of sand mixed with cement, and tamping in a richer cement/sand mixture between the bricks. The most tedious part was washing off each brick and smoothing the mortar with a fine spray of water. Then twelve hours later you just slosh the lot down really thoroughly and leave it to set. Needless to say, we are both very fit these days. Apart from a patch of sunburn on my shoulders, I am feeling no ill effects at all today.

In her next letter, Mum must have made some comment on how impressive we must appear to our neighbors, doing all this work ourselves. And how typical of New Zealanders. I responded:

May 2, 1971

New Zealanders don’t have the monopoly on do-it-yourself, you know! You should see the crowds at the handyman-type shops every weekend here.

I continued with an anecdote that shed a less than favorable light on the prejudices of some other Kiwi immigrants:

We were a little amused at another N.Z. couple we know, who have this thing about N.Z. characteristics. We had invited them to dinner, & I tried to give [our friend] directions—after all, Cupertino’s house numbering system is completely random, & I thought they might at least want to know what freeway exit to take. But she pooh-poohed the whole thing—it was “terribly American” to give directions—if they couldn’t find their way by map they weren’t self-respecting N.Zers! As it turned out, they had (inefficiently) double-booked on engagements, & couldn’t come …

Reading this exchange again after so many years, I recognize the beginnings of a shift in allegiance. I was no longer blindly loyal to the sometimes insular attitudes of my birth country. I was learning to question assumptions and beliefs about any group of people. I was learning that being an immigrant is complicated.

Saga of an unpublished novel

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a beat-up cardboard box that contains the dog-eared manuscript of my first completed novel in the US, “A Stone from the Wall.” The saga of my attempts to get it published, as reflected in letters to my parents, may get a nod of recognition from other aspiring writers.

March 15, 1972

I have finally got my book off my hands. I received an invitation last week to submit it to Houghton Mifflin Co., one of the most prestigious of the major publishing companies, so after a final frantic effort to finish typing the fair copy, it is now on its way. Whether they will buy it or not is of course another matter, but just to get an editor there enthusiastic about the idea is a tremendous boost. It is their sort of book—a serious look at a contemporary theme. My subject is racial prejudice, and the point I am trying to make is that, for a white person trying to come to terms with racial problems, the most difficult, and even painful, part is learning to recognize your own prejudices. This is mainly, of course, because the more concerned you become, the more you want to think of yourself as one of the good guys.

July 2, 1972

I was going to leave finishing this until after the mailman came today, but don’t really see the point. If I seem a bit edgy in this letter, I am. I was told by Random House that I would hear from them within 4-6 weeks. It is now nearly 5 weeks, and my heart starts hurting every time the mail truck goes up the road. It’s very tedious bracing yourself for rejection every day.

At some point I received a hand-written rejection note from the editor-in-chief of an eminent house—I believe it was Robert Gottlieb of Alfred A. Knopf—who complimented me on my “ability to make my characters come alive,” which buoyed me up for a few more rounds of submission and rejection. I no longer have the note or, for that matter, any of the many rejection notices I received.

July 25, 1972

My book showed up on the doorstep again, as expected. Disappointing of course, but this time I have decided to revise a lot of it before sending it out again. When you are writing fiction, you become in a very real sense the characters you are writing about, and sometimes it is difficult to stand back and look at them objectively—like it is difficult to look at yourself. But now I think I can see at least some areas where the characters are not interesting, or even not alive, but just vehicles for ideas. However, I am going to leave it now until fall—it’s just too difficult to work over the summer. The kids are very good, but they are something of a distraction. In the meantime I have various other articles and poems doing the rounds. They come back periodically, of course, but I figure that with enough things going, I’ll get somewhere eventually. I have had a couple of commissions from Tui [my editor at the Christchurch Press] which I have now sent off … I do still get very depressed every so often, but Tony usually manages to pull me out of it if I can’t shake it off myself. I even made a list this week of all the other things I was going to accomplish this summer. Boring jobs like cleaning the oven figure rather prominently …

November 1972

I am trying to get back to my novel, but keep getting sidetracked with new ideas [for stories and articles]. Have just finished grading a big set of students’ short stories for Millicent [the high school teacher for whom I worked]. Tremendous ideas and effort, but my main reaction as I tore each one apart was, my gosh, that’s what’s wrong with my writing too.

Discouraged, and preoccupied with other projects, I eventually gave up and moved on. As I noted in my blog essay “The Other Side of the Freeway,” I understand now why “A Stone from the Wall” never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject. I didn’t understand how much the life experiences, interests, and even musical tastes of my African-American characters might be different from those of my white characters. Though I devoured my subscription to The Writer magazine from cover to cover, the protocols of book publishing still felt like an enormous black hole. The battered manuscript box deservedly stays in the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet.

The other side of the freeway

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a battered cardboard box containing the manuscript of a novel I wrote in the early 1970s. I understand now why it never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject: racial discrimination in housing. As I reread some of the text, I recalled the shock I felt when I first grasped the magnitude of the social gaps. The descriptions that follow come from my own experience as I researched the book, and it began my involvement with the fair housing movement.

Here is the central character Karen, a newspaper reporter, visiting the black ghetto of East Palo Alto for the first time to interview the director of a community advice center:

She knew vaguely that East Palo Alto belonged to the county. … She crossed the county line now, and accelerated to get onto the overpass that spanned the freeway. As she came down the ramp on the other side, she knew she was in a different country. The road was suddenly pot-holed and bumpy, and brown dust rose in thick choking swirls from its verges. She slowed, and looked about her. Such tiny bedraggled houses, desperately in need of paint. Yards littered with junk, yet here and there a brave attempt at order and color, a flower-bed, a well-cut lawn. She came upon a few tatty shops. Surely this couldn’t be the main shopping center? Yet soon she could see the sign, NAIROBI SHOPPING CENTER, and underneath, in a language she could not understand, UHURU NA UMOJA.

She had to force herself to open the door. Lurid accounts of rapes and muggings and violence in the streets flooded her mind. Here she was the enemy. She wanted to jump back into the car and get out, away from this place.

A woman passed, with two small children, headed for the market. She looked indifferently at Karen as she passed, then turned to scold one of the children, who was whining for candy. Karen let out the breath she had been involuntarily holding, and made herself move on. … Across the road, outside a liquor store, a black knot of middle-aged men stood transfixed in time, waiting for nothing.

It was hot. The dust lifted lazily as she walked. Something about the huge trees, and the stillness of the air, brought to her mind descriptions she had read of towns in the southern states. But this was California. It did not make sense. A mockingbird flashed its wings across her path, still proudly singing.

Karen does her interview, in which she learns about the pressures of living in East Palo Alto (and also finds herself attracted to Paul, the advice center director).

She said goodbye, and walked slowly back to the car, past the Louisiana Soul Food Kitchen and the Black and Tan Barber. The heat and dust were almost unbearable.

Back across the freeway, she noticed for the first time the neatly swinging redwood sign: Welcome to Palo Alto. A few blocks further down University Avenue and it hit her like a punch in the gut. She pulled over to the side of the road and rested her head on the steering wheel, fighting back an impulse to vomit. The contrast was an obscenity. Huge magnolias here lined the street on both sides, giving deep dappled shade to the well-paved highway. Between the road and the white concrete sidewalks rose great greening mounds of juniper and ivy, and beyond them, with manicured lawns and discreet sprinkler systems, were the complacent mansions of the rich.

The nesting instinct

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

I’m wondering whether there’s some evolutionary or hormonal factor that drives women (I don’t know about men) to clean every inch of their new home when they move house. The thought came into my head when I reread a letter to my parents written when we were moving from our first apartment in Cupertino, CA to a tract house in the same neighborhood.

Feb. 2, 1970

… I cleaned the apartment, then of course rushed back here to try to get a bit more cleaning up and unpacking done. The previous owner was a pretty sloppy housekeeper – still, I guess everyone complains about the other woman’s methods. Anyway, most of the house is now more or less presentable …

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Looking for information on the topic, I found lots of material on what is called the “nesting instinct,” the urge most pregnant women have in their third trimester to scrub floors, sort sock drawers, or perform other cleaning and organizing tasks. It appears to be triggered by an increase in the body’s estradiol, the major female sex hormone, and is “an adaptive behaviour stemming from humans’ evolutionary past.”

Or, as webmd.com puts it: “Just as birds are hardwired to build nests for protecting their young, we humans are primed to create a safe environment for our new offspring.”

I wasn’t pregnant in 1970, so I looked up sites with information on spring cleaning. I found checklists, some tentative discussion of the custom’s origin in ancient traditions and religious practices, as well as practical reasons for the task, especially in places of cold winters and times of sooty wood- and coal-burning heating facilities. And on sites about moving into a house, there were checklist after checklist, all of them assuming that the previous owner/tenant is by definition a germ-carrying slob, and that the new occupant is motivated to clean every inch of the place. A few examples:

From Angie’s List:

- “Previous residents surely cleaned the bathroom, but there is no harm in scrubbing away your own way as this room can be one of the more germ-filled places in the house.”

- “The insides of all cabinets and drawers were most likely ignored by the previous tenants or homeowners.”

- “Dust the top of the doors and disinfect all doorknobs.”

From Bed Bath & Beyond:

- “Your dream home sure looked spotless during the open house. But gird yourself: No matter how clean the place seemed, it’s likely there are some dirty surprises in store for move-in day.”

[This site pays particular attention to chandelier light fixtures, crown moldings, ceiling fans, doors & knobs, refrigerator vent, dishwasher, furnace, ductwork, washer & dryer]

From The Spruce:

- “You should always do a thorough clean before your stuff arrives.”

- “The kitchen is probably the first place to start. Not only because it tends to be where icky sticky things collect, but also because you’ll want to get rid of the former tenant’s cooking smells.”

[Detailed instructions for fridge, stove, cabinets, counters, sink, walls, floors]

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

While not as freaked out about other people’s germs as manufacturers of cleaning products might wish, I’ve done a reasonably thorough cleaning of every house I’ve moved into. (Except the last; it was newly built, so apart from a little carpenter’s dust, it was pristine.) I’ve done my share of spring cleaning too, and found a kind of primal satisfaction in touching every surface of my home with a cleaning cloth. I’m wondering now whether there might be a hormonal component to the spring cleaning urge. It seems like a good excuse. I grow old. My estrogen levels have decreased. In recent years, I’ve found myself gearing up for spring cleaning and abandoning the task halfway through the pantry shelves. Maybe this spring I’ll actually finish the job. Or not.

The appeal of the picturesque

I’ve been wondering: what is it about an old house or barn that appeals so much that we describe the scene as “picturesque.” The question came up as I reread a January 1970 letter to my parents describing the purchase of a house in Cupertino, CA. Our new home was a typical early 1960s tract house with scalloped trim and prominent garage. The place was certainly not picturesque, but it was within our price range. I wrote:

It’s a very nice little house – 3 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, big sitting room with dining area at one end, small family room opening to a neat little kitchen, 2-car garage with laundry facilities in it. Very attractive inside, though not very prepossessing from the outside. However, this is just a matter of landscaping – other houses in the street are just lovely, but the garden of this one is just bare grass.

Looking back on that time, what comes most vividly to mind is another house I saw while house-hunting, a charming old farmhouse dating from the time when the Santa Clara Valley was so full of orchards it was called “The Valley of Heart’s Delight.” As I walked through with the realtor, I paused in what must have been a utility porch and mud room. The unfinished walls of the room were black with mold. The realtor shrugged when I pointed it out. The price was right, but I chose not to make an offer.

There’s a significant difference, of course, between the picturesque, which has been defined as that kind of beauty which is agreeable in a picture and a habitable structure for humans. But what is it in the human psyche that is drawn to the antique? Rummaging around on the web, I found quotes such as:

(esp. of a place) attractive in appearance, especially in an old-fashioned way

A picturesque place is attractive and interesting, and has no ugly modern buildings.

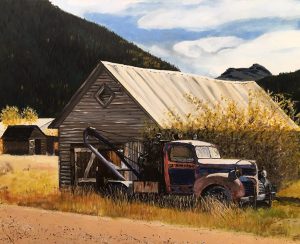

My friend Sandy Peters says it well. Commenting on a Portola Art Gallery exhibition of her husband Jerry Peters’ paintings of old battered trucks in rural settings, she wrote: They demonstrate how the beauty of nature blends seamlessly with the wisdom of age.

However, with age comes death. When we first moved to Mendocino seventeen years ago, a cabin stood among the trees along Highway 128, not far north of Yorkville. Its bare board were gray with age, the sway-backed roof shingles covered with moss. Over the years, the roof has slowly caved in, until now the cabin is a jumbled pile of boards. At first it was picturesque. Now when I drive by, I am sad.

A roof and a meal in 1968 dollars

While rereading letters dated early 1968 from California to my New Zealand parents, I discovered a conversation about the cost of housing and the cost of living generally. If you’ve seen the current astronomical real estate prices in the San Francisco Bay Area you will be mind-boggled at the numbers. For that matter, housing prices have also risen dramatically in New Zealand cities. (To take inflation into account, multiply the US 1968 numbers by 7.2)

The conversation started with mention that friends in the apartment complex where we lived had bought a house.

2 Jan. 1968

On Sunday we spent the afternoon at the J___s’ new house – they have managed to acquire a lovely rural acre running down to a creek – we are very envious.

26 Jan. 1968

You asked about the price of housing. Well, the J___s got theirs extremely cheaply, because of some easements on the property – power lines restrict building on one corner, and a road may possibly go down the side of it. Normally such a place would go for between $45,000 and $50,000 – they got it for under $35,000. Housing is generally pretty expensive here. If you want a genuine or potential slum you only have to pay about $18,000, but the vast majority of ordinary middle class suburban houses – about equivalent to the typical NZ suburban house – come in the range $22,000 to $28,000. New houses in this area, that is, the west side of the [Santa Clara] valley, are all $35,000 and up. Down payment is between 10%–25%. Which puts us out of the housing market for some time.

Just for comparison, what would an equivalent house in NZ cost now? The outer suburbs of Auckland or Wellington, for instance. It would also be interesting to compare costs of living – could you find out for me how much it would cost per week to keep house for a family like ours, for instance?

27 Feb. 1968

Thank you for the list of prices etc. Costs certainly seem to be fairly high. Your power bill is about the same as ours, and so is the telephone. Houses in NZ seem to be about half our price, but rents considerably lower – we are paying $160 a month, or $40 a week, and this is pretty reasonable for this area. To get a house we would have to pay $225 or more.

Your food bill is certainly much cheaper than mine. I have $40 a week for housekeeping, of which about $20 goes on groceries, $4 on fruit and vegetables, $5 on meat (and this is pretty frugal – we practically never eat steak, for instance. In fact, our standard of living hasn’t changed much from what it was in England.) The rest goes on miscellaneous sundries – sewing notions [I sewed all my own and the children’s clothes], postage, haircuts – at $3 a go for an ordinary cut it’s just well I don’t go in for sets, perms, etc., and the boys’ hair I cut myself.

…This seems to be turning into a grouch about costs, which is not really fair, as salary levels are comparably higher. At present we are managing to save about 10% of Tony’s salary, which is better than we have ever done.

Those new houses in Cupertino that in 1968 were selling for $35,000 are now listed at over $2,000,000. That’s eight times the inflation rate. Economists might say that’s the law of supply and demand.

The shapes of family

I still remember the tongue-lashing my teenage cousin and I received when we defended our widowed grandmother’s decision to file for divorce from her second husband. If the two of them couldn’t get along, we saw no reason why they should have to stay together. Mothers and aunts rounded on us. We didn’t know what we were talking about, they scolded. Grandma was a disgrace to the family. The Mother’s Union of our Anglican Church was going to throw her out, and her daughters were ashamed to show their faces in town.

Tauranga, New Zealand, was a tightly traditional little town in the 1940s and 50s, when I was growing up. Fathers worked, mothers stayed home with children. I didn’t know any single parent families. If there were divorcees, they were invisible. So were lesbians and gays.

My social environment in England was almost as sheltered. My friends were other young marrieds with small children. Our close of new row houses was filled with intact families like ours.

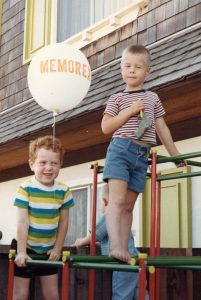

When we moved to Cupertino, CA in 1967, we lived in a complex of townhouse apartments. Each apartment had a 20 ft. by 10 ft. fenced yard. Our yard was filled with a climbing tower, a sand box, sundry tricycles, pushcarts, and other paraphernalia to keep our two small boys entertained. The neighbors helped open my eyes to other family structures: single parents, grandparents raising kids, abusive relationships.

The memory of my grandmother’s divorce comes back to me as I read a letter to my parents. After thanking them for our two-year-old’s birthday gift, I wrote:

17 Nov. 1967

Simon had a lovely little birthday party – a lunch for three little friends – after school the apartment is invaded with older kids, which would have caused problems. We seem to run a regular play centre here, what with the climbing tower and sandbox, and the new easel, with apparently unlimited supply of crayons & paper. However, the opportunities for recreation are so limited in these apartments, and so many of these kids from broken or otherwise mixed-up homes, that I guess its our contribution to the community.

There’s a self-righteousness tone to this comment, an indication of my awakening to the variety of household shapes in this new environment. A hint of defiance too. I wonder, was I getting back at my mother and aunts for their dismissal of my grandmother’s decision so many years ago?

Furnishing a house, 1960s style

A magazine clipping tumbles from a November 1964 letter from England to my parents. It’s the picture of a dinner service I won in a menu-planning competition. Looking at the geometric pattern on the dishes, I realize that the way we furnished the row house we bought that year has many elements of what is now recognized as a distinctive 1960s aesthetic: bold shapes and strong colors.

Having limited funds, Tony and I refurbished or made many pieces of furniture. The dining table he made was a heavy white plastic-veneered slab with straight, varnished wood legs. He built, and I upholstered, a sofa and side chairs with squared-off, simple lines, a copy of a set we particularly liked, but whose price was prohibitive. I made all the curtains from fabric purchased at Heal’s of London, the store that carried the trendiest of household furnishings. I wrote:

8 August 1964

The sitting room curtains are quite magnificent – deep orange flame colour, with a pattern called “Armada,” the formalised ships’ hulls giving the impression of a dark horizontal stripe.

A shag (another 1960s design element) area rug that matched the curtain’s colors helped warm up the coldness of the room. After battling the developer over the house’s color scheme, we had compromised on gray vinyl tile floor and plain white walls. In the kitchen and dining area, we covered the white with a geometric wallpaper. A photograph reveals more geometrics: the gray and white kitchen curtains, the cups and saucers on the counter.

We still have one platter from that dinner service I won. A few other items, mainly metal, have survived the years. A pewter jug purchased on board ship during our emigration from New Zealand to England still sits on our kitchen windowsill. To the right of the dinner service picture, behind a porcupine of cheese chunks on skewers, are familiar objects: salt and pepper shakers just like the ones we still use every day. I guess we, like these furnishings, can all be labeled “vintage.”