Archive for the ‘health’ Category

The best laid schemes

The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men

Gang aft agley

–Robert Burns

I’ll never forget how furious my mother was with me that day. I was about seven years old, and spending the day at my grandparents’ house while Mum ran last-minute errands. The next morning my parents, sisters and I were to leave on a camping trip, the first real vacation my family had ever had; Dad was an auto mechanic, and summer was his busiest time, with all the beach-goers flocking into our seaside town and needing help with their vehicles.

That afternoon I started to feel poorly. Grandma felt my forehead and promptly tucked me into bed. By the time Mum bustled in to pick me up the cause of my misery was obvious: my body covered with the red blisters of chickenpox.

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

The memory of my mother weeping with disappointment came back to me two decades later. My husband, children and I were living in California, and could finally afford a return trip to New Zealand, our home country, after seven years abroad. My letters to parents for the previous several months had been full of plans and itineraries. About three weeks before our scheduled flight, David, our almost five-year old, came down with chickenpox. We phoned with the news. A few days later I wrote:

11 May 1968

I did write to you earlier in the week, but it was obsolete before it was even posted, so I tore it up instead. Isn’t this business just typical of kids? Anyway, here is the present state of play: we have bookings … [revised details]… But this flight depends on Simon [our two-year-old] coming out in spots this weekend, or Tuesday at the latest. The chances are higher that we shall postpone again until the following week …

Here is my calculation of the odds: Incubation period 11-21 days. Say David came out in spots on the 11th day, and Simon, from the same contact, on the 21st day (i.e., next Friday) he has two weeks to have it over with.

Say Simon missed David’s contact, and gets it from David, he can come out in spots on the 11th, 12th, or 13th day, and has 11 days, or a reasonable chance, to be free of scabs. (The airline will take him if a doctor will certify that he is not contagious.)

Say Simon decides not to get it at all, he will have passed the 21st day by two days.

The only problem will be if he gets it from David after the 13th day. The 14th day is borderline; after that we would have to cancel. We are in a bit of a quandary as to what to do then … Meanwhile we are all twiddling our thumbs, and willing Simon to produce ‘chickenpops’, as he calls them. It seems such an awful thing to do to such an innocent little poppet, but so far he has remained obstinately clear-skinned and perky…

The ironic thing is that we had a mumps crisis last week. One of the children’s closest friends came down with mumps about two weeks ago. We flapped around for a while, seriously considered gamma globulin, in spite of the cost (about $60 just for shots for myself and the children). We had braced ourselves to go through with it, when at the last minute the doctor just couldn’t get hold of any, so decided to try a new mumps vaccine instead. This is a lifelong immunity, but doesn’t take full effect for a month. By this time, he hoped that the vaccine would have built up enough antibodies to resist the disease. So far it is working. It is quite interesting being guinea-pigs, and considerably less expensive, at only $5 each. So instead we get the chickenpox!

…I have just come in from a walk – after four days in the house with kids, I needed it, but have come back feeling more depressed than ever about the whole business.

Monday – Have postponed until 31 May…

20 May 1968

Believe it or not, Simon actually produced some ‘chickenpops’ today, so we have started believing again that we are really coming. … I’m still not really convinced that we will arrive, but as we are going in this Wednesday to pick up the tickets, I had better stir myself out of this legarthy.

The irony of this story is that when we finally arrived at Nandi, Fiji on our way to New Zealand, the immigration officer noticed that David’s smallpox vaccination was outdated. (You needed this at that time to get into New Zealand). In our panic over chickenpox, we has totally spaced on this detail. Fortunately the officer was kind “Just get it done as soon as you get there,” he said as he stamped our papers.

The red stain of near disaster

Whenever I see old blackberry canes, dark red as the stain of their summer juice, I remember blackberrying in England when my son was small, and a dark red guilt sweeps over me. I described our expedition in a letter to parents:

8 Oct 1965

We went blackberrying on St. Ann’s Hill, not far from here. Got a lovely lot—have been busy making jelly, pies, etc. David had a wonderful time—it was so sweet to see the solemn single-mindedness with which he set about collecting his berries—and he didn’t eat a single one until Tony offered him a handful—to comfort him when he tumbled down a slope into a patch of brambles.

Modern American parents would probably be horrified at how lackadaisical we young mothers in England were about supervising our children’s play. Once the daddies were gone to work, our little close of twenty-eight row houses was almost completely free of traffic. The kids, twenty of them under school age, ran in and out of each others’ houses and romped together across the grassy front yards.

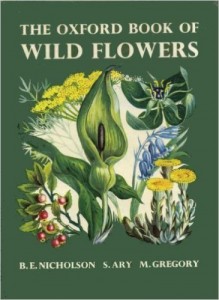

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

The Monday after our blackberrying expedition, I went out to gather up two-year-old David for lunch. I found him and his little friend in a still-rough corner between the housing blocks. His mouth was stained red. “I picking blackberries, Mummy,” he announced cheerfully. I took one look at the berry-laden plant, then rushed back to the house. My Oxford Book of Wild Flowers confirmed my guess: Deadly Nightshade.

While Tony, who had come home from work for lunch, went to tell the mother of the other child what had happened, I tried everything I knew of to make our baby throw up. Nothing worked. We called an ambulance. Since I was within a week or two of giving birth to our second child, a neighbor, seeing the ambulance, came over to wish us well. I am still grateful that when she learned the story, she called the police, and still guilty it hadn’t occurred to me that other children might be involved. Some days later I wrote to parents:

Watercolor illustration by Barbara Nicholson in The Oxford Book of Wildflowers, Oxford University Press, 1960. Shown are: Comfrey, Common Mallow, Musk Mallow, Deadly Nightshade, Duke Of Argyll’s Tea Plant, and Woody Nightshade.

13 Oct. 1965

The police organised all the rest of the kids in the close whose parents couldn’t prove they were somewhere else that morning into another convoy of ambulances for a mass stomach pumping session. About a dozen altogether involved, of which four (including David) were confirmed cases, though they decided to keep the whole lot overnight for observation, just in case.

Meanwhile the newspapers had got hold of the story. We refused to see them at the hospital, but when we got home about 7:00—completely exhausted, & having had nothing to eat since breakfast—we were invaded by a posse of reporters. A highly garbled & exaggerated account appeared the next day. I suppose it’s not every day one makes the front page of the Daily Mail, the Daily Mirror, & the BBC News, but I shouldn’t care for the honour to happen again.

Anyway, the story ended well—all the kids were discharged the next morning, with none but the hospital staff any the worse for wear—in fact the sister-in-charge of the children’s ward where the confirmed cases were confessed that she hadn’t known that four such tiny boys could get so involved in riots and punch-ups all up and down the ward, and they were very pleased to see the back of them.

Fingernails on glass

The visiting baby, almost two years old, sat alone and silent by the ribbed glass door of our row house in Egham, on the outskirts of London. He paid no attention to our chatty, energetic infant of the same age, nor even to his parents. Instead, he ran his tiny fingers obsessively over the ribs of the glass. Watching him as I fixed tea for our guests, I was uneasy.

A letter to my parents dated 20 April 1965 says nothing of this unease. Instead:

We had visitors on Sunday – Steve & Derek Shirley & their little Giles, who is the same age as David. We hadn’t seen them for quite a while, & had a very pleasant day.

That was the last time we saw the Shirleys. Recently I have been reading Dame Stephanie (Steve) Shirley’s memoir Let IT Go, to try to understand what happened to our year-long friendship. The answer is devastating.

In early 1964 I had interviewed Steve by phone for an article that ran in the Guardian about women programmers and her new business Freelance Programmers. A few months later I gushed to parents:

30 April 1964

A couple of weeks ago we went to visit a very pleasant couple – the woman I interviewed (over the telephone) for my article on computer programmers. She has a baby the same age as David, and also works at home making up programmes – that is, the detailed instructions to be fed into a computer to do a required job. Anyway, we liked each other very much even over the phone, and she invited us to a meal to meet properly. They have a marvellous little stone cottage up in the Chilterns, right out in the country, with apple trees and daffodils, low oak beams, a huge log fire, and a grand piano squeezed into the front parlour. It sounds like a setting from a romantic novel, and that was the feeling even when we were there, that everything matched so well that it couldn’t be quite real. And a remarkable affinity too, between us as people. A bond to start with of course — it was the interest of her story that got me a place in the Guardian, and she credits me with the terrific boost to her business – she now has 20 other home-bound women working for her, and is forming herself into a limited company, and with giving her the confidence to get started. Then Derek is also a physicist [like Tony], reserved, very musical, and Steve and I found that our feelings and ideas agreed on all sorts of points.

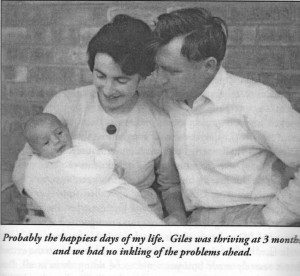

At that time Giles and our David were eleven months old. Steve writes in her memoir:

The catastrophe had crept up on us. It must have been in early 1964—when he was about eight months old—that we first began to worry, on and off, that perhaps Giles was a bit slow in his development: not physically, but in his behaviour. He was slow to crawl, slow to walk, slow to talk; he seemed almost reluctant to engage with the world around him. These concerns took time to crystallise—as such concerns generally do—and the first time I went to a doctor about them I couldn’t even admit to myself what was worrying me. …

My letters for the rest of 1964 are full of references to our new friends: visits back and forth, parties, conversations. In June I wrote: We liked them even more, if possible … isn’t it strange how people sometimes just click.

Meanwhile, Steve writes:

By the end of that year, however, there was no avoiding the observation that Giles was losing skills he had already learnt. … [He] had never become chatty. And now he fell silent. …

Months of desperate anxiety followed, in which there seemed to be little that we could do except fret. …

My lovely placid baby became a wild and unmanageable toddler who screamed all the time and appeared not to understand (or even to wish to understand) anything that was said to him…

By mid-1965 Giles had taken up weekly residence at The Park [the children’s diagnostic psychiatric hospital in Oxford] while the doctors there tried to work out what was wrong. Nothing I can write can capture the enormity of the sorrow that that short sentence now brings flooding back to me. …

Finally, in mid-1966, the specialists overseeing Giles’s case [at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children] delivered the devastating but unarguable verdict: our son was profoundly autistic, and would never be able to lead a normal life.

I understand now that our friendship with the Shirleys could not survive. Being with us would have been painful for them. There was too much unspoken, too much contrast between their child and ours. For a short time, we loved them. Even now, a sadness returns.

Postscript

Derek and Steve spent the rest of Giles’s short life seeking appropriate and supportive care for him. (He died at age 35.) Steve’s business flourished. She has poured her considerable wealth into philanthropy, primarily to support “projects with strategic impact in the field of autism spectrum disorders.”

Dame Stephanie Shirley: Let IT Go, Andrews UK Ltd., 2012