Archive for the ‘personal growth’ Category

Looking back at a life

The cover image is a detail from the watercolor painting “Under the Fog” by Mendocino Coast artist Karen Bowers.

So far this blog has been a form of memoir: small stories and reflections about some aspect of my history. Today I break that pattern to tell you about another aspect of my writing life, poetry. I’m excited to announce that my latest collection of poems, Horizon Line, will be published next April by Main Street Rag Publishing Co. The publisher has set up a handsome webpage where you can place pre-publication orders at a substantial discount from the $14 list price.

Horizon Line is also a kind of memoir. The title poem sets the theme of the book: “To limn a life in perspective …” From my house on the Mendocino Coast in Northern California, I watch the sea fog move in and out, changing as it does the viewer’s perception of where the horizon is. I use this variability as a metaphor for what it’s like to look back on my life. Here’s the poem in full:

Horizon Line

To limn a life in perspective

the artist first defines

a horizon line eye level to the viewer.

From my hill of years the horizon

is fluid as in watery, but also

as in unpredictable.

On the sea’s face a wall of fog

moves in and out like histories

remembered and forgotten.

Sometimes silver striates the sea

with such a glitter of insight

I am bedazzled and cannot look.

Sometimes fogbank and ocean

merge with such blue-gray unity

it seems the horizon rises

so that I stand on the shore

dwarfed by a surf of knowledge

that pounds at my ignorance.

Sometimes the sea becomes invisible

the white air a questioning emptiness

a finger-touch of damp against the cheek.

Indigo Moor, Poet Laureate of Sacramento Emeritus, said this about the collection:

In her new poetry collection, Horizon Line, Maureen Eppstein takes an imagistic look at the systole and diastole of the immigrant experience. Divided into four chambers, Horizon Line presents a New Zealand eye’s view of the American experience, from the landing on these shores, through the struggle for spirituality, and, finally, to the unerring clarity of the clearing at the end of the path.

Like a retrospective exhibition of an artist’s work, I see this book as a summing up of my spiritual and artistic journey. I would be honored to have you as one of my readers. Again, here’s the link for ordering Horizon Line:

A spat in slow motion

A spat between parent and adult child is different when conducted on flimsy blue international air letter forms. For one thing, it happens in slow motion: weeks pass between riposte and retort. For another, it’s solitary: neither side can see the angry tears of the other. And it’s documented; that is, if letters are kept. My mother kept all mine, and gave the bundle back to me. I constantly regret that I didn’t keep hers, so have to guess at the comment to which a letter of hers or mine would have responded.

A typical example happened in late 1971. Decades later, as I read through my old words, I recognize patterns of individuation familiar to every psychoanalyst.

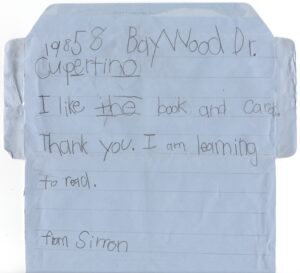

It started with a postscript to a birthday thank-you note my six-year-old son had written on Nov. 13, 1971.

At the bottom of the page I’d scrawled:

Do I assume that you have given up writing to me?

Mum’s response, as I remember it, was to the effect that if she wrote to one member of my family, it was to be assumed that she was thinking of us all. Here’s my response:

Nov. 23, 1971

I’m sorry that you got so uptight about my comment, Mum. However, I think we should clear up some basic misunderstandings about the children. I am delighted that you have written to them, and they are too. They think it is pretty special when an adult relative takes an interest in them. But it is very important to me that the kids be seen as individual people, with interests and responsibilities of their own, and this includes developing communications with other adults outside the immediate family. This, I think, is a reaction to my own childhood, when you tended to take over any attempts we made to establish relationships with other people. Now don’t get upset – I’m just trying to show you how I see myself, and how I see my kids. If you only have time to write to the kids, that’s O.K. I’ll encourage them to answer your letters, but there may be some long gaps. They are not big enough yet to handle a regular correspondence. But I have no intention of taking over the responsibility for them, nor of regarding your letters to them as some sort of gimmick substitute. I am an individual person too, and I haven’t had a letter from you since August.

We made up our differences in the next round of letters. In response to her plaint about the difficulty of being a parent, I wrote:

Dec. 14, 1971

I know what you mean, Mum, about bringing up kids. I sometimes wonder what these two will hold against me when they grow up, and it’s sure to be something I’ve never thought of.

Education for perspective transformation

I’ve rummaged through my old black filing cabinet to no avail; I can’t find the draft of my early 1970s interview with Georgia Meredith, director of the re-entry program for women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, CA. I liked Georgia, a warm, caring person who made every woman she met feel welcome in her college program.

Jack Mezirow with his wife Edee, whose return to college in middle age helped spark his theory of transformative learning.

I scoured the Internet, and found one reference to her, in the acknowledgments for a 1978 academic paper on the phenomenon of mid-life women returning to school. The author is Jack Mezirow, who was a professor of adult education and director, Center for Adult Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. Georgia Meredith’s Foothill College program was part of his nation-wide study of re-entry programs for women in community colleges.

Older women on college campuses were a new phenomenon in the early 1970s. Mezirow’s data show that the number of women aged 25–34 attending college rose more than 100 percent from 1970 to 1975. According to his obituary (he died in 2014) Mezirow’s interest was party inspired by watching his wife return to graduate school in middle age.

His research project’s primary thrust was “to identify factors that characteristically impede or facilitate the progress of these re-entry programs.” His findings led to the theory of perspective transformation, which Mezirow describes as “a critical dimension of learning in adulthood that enables us to recognize and reassess the structure of assumptions and expectations which frame our thinking, feeling and acting.” He writes:

“For a perspective transformation to occur, a painful reappraisal of our current perspective must be thrust upon us. Among the re-entry women whom we interviewed, the disturbing event was often external in origin —the death of a husband, a divorce, the loss of a job, a change of city of residence, retirement, an empty nest, a remarriage, the near fatal accident of an only child, or jealousy of a friend who had launched a new career successfully. These disorienting dilemmas of adulthood can dissociate one from long-established modes of living and bring into sharp focus questions of identity, of the meaning and direction of one’s life.”

He lays out ten steps in the transformation cycle:

- A disorienting dilemma;

- Self-examination with feelings of guilt or shame;

- A critical assessment of sex-role assumptions and a sense of alienation from taken-for-granted social roles and expectations;

- Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change;

- Exploring options for new ways of living;

- Building competence and self-confidence in new roles;

- Planning a course of action and acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans;

- Provisional efforts to try new roles;

- Building of competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships; and

- A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by the new perspective.

Mezirow notes that the scope of re-entry programs expanded as the need to focus on self-exploration, career development and personal growth grew increasingly apparent. Some community colleges needed to make changes in entrance requirements. In many classes, writing based on personal experience was accepted in lieu of academic knowledge of a subject. Cohorts of adult students were kept together to encourage mutual support and encouragement. Classes were often scheduled into blocks of time that fitted with children’s school time. Colleges set up child care facilities, drop-in women’s centers, resource referrals.

“All of the programs,” says Mezirow, “are clearly aware that they exist to provide specialized support for women who are effecting a transition in their lives. Since the women are at different phases in this transitional process, their needs vary. … The central goal …is perspective transformation —helping women to see themselves and their relationships in new ways, which require taking responsibility for their lives, examining their options, and formulating new life plans. It is a unique mission in higher education.”

Liberation by Strobe Light

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

At the opening forum, my friend Judi and I recognize a few women we know. There is a feeling of bonhomie among the attendees, I have written in my notes. After the introduction we are shown a women’s lib segment from the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family”. Women roar with approval at Gloria’s feminist attitudes, chatter noisily during commercials.

The surroundings for my first breakout session are inauspicious. Out of the rain and into a Foothill College classroom plod two dozen women like myself, suburban housewives, thirtyish to middle-aged, dripping umbrellas. The desks have been pushed back against the cream-colored walls, and the chalkboards are still scribbled with students’ assignments. Self-consciously we obey the call to take off our shoes and sit on the floor. The instructor, in powder blue leotards, is already making pumping movements with her arms.

In formal dancing, she explains, the woman is led by her male partner. But today’s kids dance apart, doing their own thing. We are going to pretend like we are kids. We heave up our sagging muscles. The lights go out. The music comes on, a strong rock beat. A strobe light flickers. I have never seen a strobe before. I am fascinated by the jumping shadows. Impossible to see any other person clearly. The classroom is disappearing, and we are no-place. Though we are crowded together, we are each alone, in our own darkness. At first we copy the movements of the instructor, but imperceptibly private fantasy takes over.

From my mother I learned to fear my sexuality. Now I am doing a sexy dance, gyrating my body in a collage of distant memories. I see again the smoky crush of teenage bodies glimpsed through a basement doorway at a country club near Syracuse, NY. It was 1962; the Twist was just coming in. Terrifying, beautiful, and my fear was mixed with envy of these kids little younger than myself, who could accept their bodies’ needs and express them freely.

My fingers flicker in the strobe light, twenty fingers instead of ten, flying over the keyboard of an imaginary concert grand. I am strong. I am ambitious. I am free. The beat of the music rises to a climax. My body is soaring to a rhythm of its own. I have flown back fourteen years, back to Syracuse, NY, back to the doorway of the smoky basement. I enter the door and mingle with the grease and sweat of the dancers. I am no longer afraid. The tape ends, the lights come on, and we flop exhausted onto the schoolroom floor.

My next workshop is titled “Changing Images.” A large wood-floored room in a gymnasium complex, walled with mirrors at both ends. Again we take our shoes off, and lie on the floor to do a relaxation exercise. “Breathe … out. Now let’s see what happens when we loosen our clothes. Those of us that have belts on, let’s undo them. Let’s unbutton our slacks. There now, isn’t that more comfortable?” We are given a little pep talk on the influence of other people on our fashion choices, then break up into small groups to discuss how we feel about our clothes. I tell about my conservative wool suit, and how mod and worldly and competent I felt when I dressed it up with cream opaque pantyhose and body-shirt to go out and do an interview. A striking single girl confesses that she usually winds up wearing a sexy dress to go to a party where there may be new men. A matron in trim blue slacks and floral shirt tells how she automatically thought of wearing a knit suit to this workshop, until she read in the paper the invitation to wear “comfortable” clothes. She wishes she could find her own style – everything she buys turns out to be too conservative for what she thinks may be the real her, yet very suitable for her role as wife and mother, church-goer, active member of the PTA at her kids’ school. We try on a few wigs and clothes. It’s fun, but inconclusive – there are not enough things to do much with.

I meet Judi at the cafeteria for lunch, and we trade notes. At her clothing workshop, the first of her day, two women had stood conspicuously at the side, refusing to soil their clothes by lying on the floor. Everyone now is very chummy. The cafeteria is crowded. I hadn’t realized there were so many women here. The luncheon speaker gives a brief potted history of the women’s movement. Her voice is rather flat, and I have read it all before anyway. I look at the mural from the morning’s painting session. It is very militant. I look for the positive, affirmative images. Not many. In a flash I know what I want to paint.

My last workshop of the long, full day is a painting session. In theory, we are to paint our reaction to the clip we were shown of the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family,” in which Archie’s wife Gloria expresses feminist attitudes and Archie berates her. But that was early this morning, at the introductory forum. A lot has happened since then.

Most women paint their reactions to the day. One painting is of a huge orange cloud, turbulent, stormy, but beautiful, and raining golden rain onto a green hillside. This was how she saw what was happening today, says the painter. The stirring of new ideas was exciting, but also scary, and in the long run it would benefit humankind.

Many women paint themselves. “This is me when I can’t cope,” writes a mother from a wealthy suburb, whose dark green and black picture shows a figure in bed under the covers, surrounded by black smoke and scary faces. Another draws a bright fire arched over by a brown form. “The brown shape is her man,” says the painter. He is both protecting her from the outside world, and smothering her fire so it can’t get out.

My image comes out fast, so fast I keep running out of paint on my brush. I draw the arms first, in dark, strong red, reaching up, hands wide open. A smiling face, a body, a quick angle of a dress to show that she is female. “Reach out!” I shout in red paint underneath. Then quickly back to the table to find some yellow paint. Bright yellow light scribbles itself behind the figure. She looks too sketchy. Pour the yellow paint into a remnant of blue to give her a green dress. Green hair? Why not? “This is where I am at,” I tell my fellow painters. “I have broken out of my chains.”

Why we travel

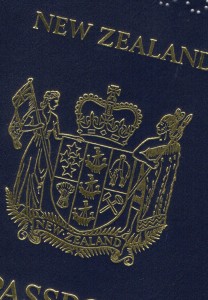

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

In 1968, after nearly seven years abroad, my husband and I, along with our two young children, paid a return visit to New Zealand, our homeland. My letters to parents after that visit indicate that we felt unsettled and were exploring how we could return permanently. Unfortunately, I no longer have the letter in which my mother must have suggested we would have been better off if we hadn’t left in the first place. But I do have my answer. Reading it again, I’m struck by how relevant my defense of the value of travel still is.

6 August 1968

A big question you asked, Mum, with a number of overtones. I think you really would have preferred your family to be more like [her sister’s children], wouldn’t you? I envy them too, in a way, settling down in the neighbourhood in which they were brought up, sharing common interests and activities with their parents and their local community.

It would have been simpler to have stayed at home. But the question is, whether you want a peaceful, comfortable life, or whether you need to know yourself. It does no harm to strip away a few illusions. The most important thing about travelling is that you quickly lose the complacent assurance that your own little set of values holds good for everybody. It is only by getting away from NZ that you can begin to see the country and its people in perspective, and it is only by being a foreigner in a different community that you can learn to be objective about social attitudes and customs.

I would be very sad not to have seen the things I have seen. It is not that our perceptions are dull in New Zealand, just that in many areas they cannot be awakened. All the art appreciation we had at school was poor second-hand stuff compared to our first sight of original Rembrandts in New York. History was unreal too, until we walked through the streets of London, or found, in the crypt of a Mediaeval abbey, a Saxon chapel built of masonry filched from Roman ruins. Childhood fairy stories had little meaning until I saw castles and village greens, and crooked pink cottages with overhanging thatch and winding sprays of apple blossom and ducks on a pond.

Of course there are difficulties, one being that it is very easy to finish up with a splendid pile of memories, and no homeland. But on the other hand, I now have a better idea of what sort of person I am, and this to me is more important.

Night train in winter

New Zealand’s Volcanic Plateau in daytime. Image from https://www.flyingandtravel.com/skiing-north-island-whakapapa-ruapehu/

An image haunts my mind like an old song in a minor key. From a train window late at night, a desert plateau spreads into the distance. In the foreground, scattered clumps of tussock, stiff with frost, emerge from a dusting of snow. On the horizon, three volcanic cones gleam white against the blackness. The scene is both bleak and beautiful. Tranquil even. A calmness fills me as I remember.

The year was 1968, the place the center of North Island, New Zealand, somewhere north of Ohakune on the Main Trunk Line. I was traveling by train, alone, to a funeral.

It had been a tense few months since my husband and I, with two young children, had decided to make the trip back to New Zealand, our home country, to visit our families. First there was boundary-setting to do with my mother on how much relation-visiting I would allow her to inflict on my shy infants. A few weeks prior to our departure date the children developed chickenpox, one after the other, pushing our schedule further into New Zealand’s winter and upending an itinerary that carefully divided our limited time between my husband’s family and mine. On arrival, I discovered my mother had sabotaged this division by taking a motel room in my mother-in-law’s town. Each day she ensconced herself in mother-in-law’s tiny living-room, dragging my embarrassed father and school-age sister with her. Other sisters later told me they’d remonstrated with her, but she’d insisted she had a right to see her long-gone daughter as soon as I arrived. My mother-in-law was gracious, but I was furious on her behalf.

Then fate intervened. On a night of heavy rain, my maternal grandmother’s husband stepped from between parked cars into the path of an oncoming truck. I did not know my step-grandfather, since he and grandma married about the time I left for college. But grandma had been an important part of my childhood, and she loved this man, so it mattered that I go to the funeral. Leaving the children with their father and his mother, I set out on the overnight journey. First a railcar from New Plymouth, on the west coast, which connected at Marton with the Night Limited express that ran each night between Auckland and Wellington.

I knew this train, having ridden it back and forth many times when I was in college. There was comfort in the familiar sway and smell of the overheated, stuffy carriage, the faded red plush covering high-backed seats, the clackety-clack of the wheels. There was peace too. For the first time since the children were born I was alone, with no responsibilities.

Beyond the desert and mountain vista on the Volcanic Plateau, the chuff and grind of the diesel engine became more labored as the narrow-gauge track rose into a more broken landscape, with forest a dark overhang outside the window. Then Taumarunui Station at 2:00 am, the refreshment stop, where bleary passengers streamed into the tea-room for meat pies or slabs of yellow pound cake and milky tea in thick white china cups. Sometime around dawn, a stop at Te Kuiti where relatives met me for the two-hour drive to Tauranga, where the funeral was to be held. Calmed by the journey, I willingly renewed acquaintance with uncles and cousins and aunts I’d argued with my mother about seeing.

Looking back, I understand what that spare, snow-covered landscape was telling me: that the land is vastly more important than human quarrels, that I needed to let go of my day-to-day tensions and anxieties and become merged with the wholeness of the earth.

Uncles & cousins & aunts, oh my!

Recently, while reading Michael Krasny’s new book, Let There Be Laughter, I came across the Yiddish word naches, which Krasny defines as “the joy and pride a parent derives from a child’s accomplishments.” High on a mother’s list of accomplishments for her daughter would be the production of beautiful grandchildren. It was an ‘Aha!’ moment. I’d been re-reading some of my 1967-68 letters to parents (my mother saved them all and gave them back to me) and thinking about the strained mother/daughter relationship the letters revealed.

The occasion was our first visit back to New Zealand. It had been seven years since we left our birth country, and twelve years since I had spent more than a week or two with my parents. In the meantime I had earned an advanced degree, begun a career as a writer, married, moved to England, had a couple of children, moved to California. I had kept in touch faithfully through fortnightly letters but had had none of that face-to-face interaction that helps define a relationship.

I was wildly excited about the trip:

18 Sept. 1967

I have a bit of news that I have been saving up, partly because I still scarcely believe it myself – we are hoping to come for a visit to NZ about the middle of next year, probably in May. It will only be for a month – you get a cheaper excursion rate for 28 days – but hope that will be long enough to see everybody again, & for the children to sort out who all the vague names of grandmas, uncles, etc. are – David [our 4-year-old] has them hopelessly confused at the moment.

1 Oct. 1967

[On news that sisters & cousins were having babies] It will be fun to meet all these new members of the family – they certainly seem to be mounting up.

31 Oct. 1967

[re Christmas presents] Like you, finance is a bit low this year – as you can imagine, we are needing to save very hard for this trip.

My next letter has a firmer tone. With the help of a marriage & family therapist friend (thank you, Linda G.), I’ve been researching the psychology of mother/daughter relationships and discovered the Jungian concept of individuation, the process of becoming aware of oneself as a being separate from one’s parents. I also learned that tensions are normal in the parent and adult child relationship during this process of separating and setting boundaries.

17 Nov. 1967

I gather that preparations are already being made for our homecoming in May. I hope you realise that our time is going to be extremely limited. We hope to divide most of it between you & [my husband’s mother], but also must go to Christchurch for a few days, and also have friends around the country that we hope to visit. So you would do well to reckon on about a week (don’t forget flying time is included in the 28 days). This week will have to include relations too. The plan for an open day or weekend sounds a good one. I had better make it plain from the start that, apart from our immediate brothers & sisters, and possibly grandparents if they are too infirm to travel, we are not going to do any relation-visiting. For one thing, it wouldn’t be fair to the kids, dragging them round from one set of strange faces to another. If you are going to get to know them at all, which from our point of view is the purpose of the visit, we will need a quiet domestic atmosphere with as few strange faces as possible. It took David four months to adjust to living in this country. Also, two days of being an exhibition piece is about as much as T. or I could stand – we are pretty unsociable types!

Here’s where the Yiddish concept of naches comes in. Looking back, I realize now that it mattered deeply to my mother to be able to show us off. She had never seen our children, her first grandchildren, other than in photographs, and she had idealized them. But as a young mother, I was having none of it:

5 Dec. 1967

Glad you see my point about visiting relations, though reading your letter again I have a suspicion that you intend to have them turning up all the time anyway. If this is so, please think again. I know, Mum, you love to have your family about you, and find it hard to understand my attitude. But to me my family is my husband and children, and next, my parents and brothers and sisters. Now I shall be delighted to meet all my uncles and my cousins and my aunts, but since practically all of them are almost total strangers, it would be much easier on us to restrict their visits to a definite two days, and leave us free for the rest of the time to do what we came for, which is to visit you.

In my psychology reading I came across another concept, filial maturity, explained as:

1) By early adulthood, particularly in the 30s, taking on the responsibilities and status of an adult (employment, parenthood, involvement in the community), the child begins to identify with the parent.

2) Eventually, the parent and child relate to each other more like equals.

When I wrote these letters about our forthcoming trip to New Zealand I was 29. After fifty years of being a mother and a grandmother, I now understand why my mother and I were at odds. I’m sorry she had to deal with such a difficult and demanding daughter. I also know this was the way it had to be.

The woman on the moor

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The ring is nothing fancy: a cabochon of amethyst quartz clumsily set in a plain silver bezel. No magic symbols engraved on the back. Yet it is a talisman. Whenever I wear it, I hear in my mind the unspoken message of the woman who sold it to me.

The year was 1966. Knowing it might be our last year in England, our family (husband, two infant boys and me) took a summer trip through England and into Scotland, staying mostly in private homes that offered bed and breakfast. A farm in the Peak District of Derbyshire. Across the Yorkshire Dales to Huddersfield and Keithley, from whence my paternal grandfather had emigrated as a young man to New Zealand. Up to a gray stone village on the moors to take tea with a sweet great-aunt who had married and stayed behind when her siblings left, and whose knowledge of the whole New Zealand branch of the family put me to shame. The Lake District, lowering with storm clouds and redolent with Wordsworthian cadences. A stone circle near Keswick. Hadrian’s Wall, a loch in Scotland. Yellowing pictures now fill a photograph album.

The little roadside shop was somewhere in the northern hills of England, on our way home. A gray, damp day, a gray, bleak building. Nothing much else around. We all needed a break from driving, so we stopped. Quickly bored with the arts & crafts contents of the shop, our toddler and the baby drifted outside with their father. I lingered, drawn to the young woman attendant, who sat at a table threading beads into a necklace. A knitted shawl around her shoulders, long mousy hair falling in a braid down her back. We chatted. She had left an unhappy relationship and was determined to survive on her own.

She had the confidence I lacked. Brought up in a conservative culture and married young, I was struggling with a sense of powerlessness in my traditional wife-and-mother role. There were times I felt trapped, and thought of escaping with the children back to New Zealand. But this would have felt like defeat. Besides, it was impractical. I had no money to pay for fare, no clue about how I would manage on my own once I got home.

My encounter with the woman on the moor was brief. I never learned her name. But the amethyst ring symbolizes an unspoken pact between us. What I gave her was good wishes and payment for her work. What she gave me was confidence that I too could find my inner strength. This is what I remember when I wear it.