Archive for the ‘Education’ Category

Sharing the joy of language

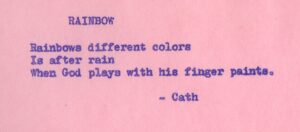

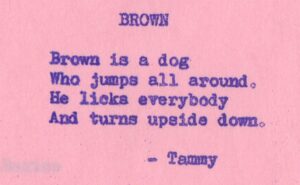

In my old black filing cabinet I find a treasure: a few stapled sheets of pink copy paper printed with the unmistakable purple ink of a ditto machine. It is the output of my first poetry teaching gig. I explain in a letter to my parents.

In my old black filing cabinet I find a treasure: a few stapled sheets of pink copy paper printed with the unmistakable purple ink of a ditto machine. It is the output of my first poetry teaching gig. I explain in a letter to my parents.

March 1, 1971

I am starting on Friday teaching one hour a week at [my son’s] school. This is what they call a scramble program, where 1st, 2nd and 3rd graders (6-9 yr-olds) are all mixed together to take activities of their own choice, from a list that includes ceramics, folk-dancing, tennis, guitar playing, cookery, woodwork, arts & crafts, etc. The teachers and mothers involved get to teach whatever they are interested in. I am taking a group who are interested in writing poetry. It should be fun, but requires a lot of preparation.

As a university student in New Zealand I had chosen not to make teaching my profession. I’ve not regretted this decision. But over the years I have enjoyed the challenge of teaching short-term writing programs, though even this first one had its moments.

As a university student in New Zealand I had chosen not to make teaching my profession. I’ve not regretted this decision. But over the years I have enjoyed the challenge of teaching short-term writing programs, though even this first one had its moments.

March 29, 1971

My poetry class is coming along quite well, though conditions were a bit poor last week – it was raining, & all the frustrated outdoor games kids crowded into the library too, & my poor kids couldn’t get into the mood.

At the end of the program I would have made enough copies of the pink sheets for all the children in my group to take home. I still remember the frustration of making ditto masters, using a manual typewriter with the ribbon removed. Any mistake and you had to start over. I still remember the smell of the alcohol solvent that permeated the printed pages. I also remember the children’s joy in the power of language.

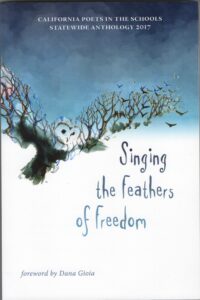

Today I’d like to give a shout-out to California Poets in the Schools, a program that not only places poet-teachers in classrooms, but also provides training and resources to help them in their work of “empower[ing] students of all ages throughout California to express their creativity, imagination, and intellectual curiosity through writing, performing and publishing their own poetry.” And I’m in awe of the technologies that support a quality of publication way beyond my pathetic purple dittoes.

Education for perspective transformation

I’ve rummaged through my old black filing cabinet to no avail; I can’t find the draft of my early 1970s interview with Georgia Meredith, director of the re-entry program for women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, CA. I liked Georgia, a warm, caring person who made every woman she met feel welcome in her college program.

Jack Mezirow with his wife Edee, whose return to college in middle age helped spark his theory of transformative learning.

I scoured the Internet, and found one reference to her, in the acknowledgments for a 1978 academic paper on the phenomenon of mid-life women returning to school. The author is Jack Mezirow, who was a professor of adult education and director, Center for Adult Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. Georgia Meredith’s Foothill College program was part of his nation-wide study of re-entry programs for women in community colleges.

Older women on college campuses were a new phenomenon in the early 1970s. Mezirow’s data show that the number of women aged 25–34 attending college rose more than 100 percent from 1970 to 1975. According to his obituary (he died in 2014) Mezirow’s interest was party inspired by watching his wife return to graduate school in middle age.

His research project’s primary thrust was “to identify factors that characteristically impede or facilitate the progress of these re-entry programs.” His findings led to the theory of perspective transformation, which Mezirow describes as “a critical dimension of learning in adulthood that enables us to recognize and reassess the structure of assumptions and expectations which frame our thinking, feeling and acting.” He writes:

“For a perspective transformation to occur, a painful reappraisal of our current perspective must be thrust upon us. Among the re-entry women whom we interviewed, the disturbing event was often external in origin —the death of a husband, a divorce, the loss of a job, a change of city of residence, retirement, an empty nest, a remarriage, the near fatal accident of an only child, or jealousy of a friend who had launched a new career successfully. These disorienting dilemmas of adulthood can dissociate one from long-established modes of living and bring into sharp focus questions of identity, of the meaning and direction of one’s life.”

He lays out ten steps in the transformation cycle:

- A disorienting dilemma;

- Self-examination with feelings of guilt or shame;

- A critical assessment of sex-role assumptions and a sense of alienation from taken-for-granted social roles and expectations;

- Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change;

- Exploring options for new ways of living;

- Building competence and self-confidence in new roles;

- Planning a course of action and acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans;

- Provisional efforts to try new roles;

- Building of competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships; and

- A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by the new perspective.

Mezirow notes that the scope of re-entry programs expanded as the need to focus on self-exploration, career development and personal growth grew increasingly apparent. Some community colleges needed to make changes in entrance requirements. In many classes, writing based on personal experience was accepted in lieu of academic knowledge of a subject. Cohorts of adult students were kept together to encourage mutual support and encouragement. Classes were often scheduled into blocks of time that fitted with children’s school time. Colleges set up child care facilities, drop-in women’s centers, resource referrals.

“All of the programs,” says Mezirow, “are clearly aware that they exist to provide specialized support for women who are effecting a transition in their lives. Since the women are at different phases in this transitional process, their needs vary. … The central goal …is perspective transformation —helping women to see themselves and their relationships in new ways, which require taking responsibility for their lives, examining their options, and formulating new life plans. It is a unique mission in higher education.”

An arithmetical awakening

From my old black filing cabinet, a letter to my parents:

Cupertino CA, 18 August, 1967

I have enrolled for an evening class. There is a very new (actually still under construction) junior college about 5 min. drive away, so have decided to prove or disprove a long-held theory of mine that I could have done maths if I had been given the chance.

In my New Zealand high school in the 1950s, academic-streamed students were divided into two programs: languages/arts or science/maths. Since I was a girl, with strong writing skills, the choice was obvious to the decision-makers. I was given a year of basic arithmetic with some beginning algebra thrown in, and that was it. I’d struggled with long division in elementary school, and learned math tables by rote, as everyone did. In college I infuriated my math student friends by continually asking “Why?” when they tried to explain math concepts. “That’s just the rules,” I was told.

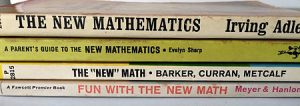

The class I took at the brand-new De Anza College in Cupertino was titled “Structure of Arithmetic”. It had a subtitle: “For Parents Who are Confused about the New Math.” New Math was a short-lived school curriculum in the 1960s that emphasized understanding the rule-systems that underlie numbers, writes Fred Martin, computer science professor at University of Massachusetts Lowell, blogging on the Computer Science Teachers Association site. He remembers it from personal experience and loved it. I learned that the decimal system is arbitrary and numbers could be expressed in any base. That was fascinating. Of course, I was the kid who learned his times tables for fun.

A Wikipedia overview notes:

Parents and teachers who opposed the New Math in the U.S. complained that the new curriculum was too far outside of students’ ordinary experience and was not worth taking time away from more traditional topics, such as arithmetic. The material also put new demands on teachers, many of whom were required to teach material they did not fully understand. Parents were concerned that they did not understand what their children were learning and could not help them with their studies. In an effort to learn the material, many parents attended their children’s classes. In the end, it was concluded that the experiment was not working, and New Math fell out of favor before the end of the decade, though it continued to be taught for years thereafter in some school districts. New Math found some later success in the form of enrichment programs for gifted students from the 1980s onward.

In a New York Times essay on the politics of math education, Carnegie Mellon historian Christopher J. Phillips writes:

Debates about learning mathematics are debates about how educated citizens should think generally. Whether it is taught as a collection of facts, as a set of problem-solving heuristics or as a model of logical deduction, learning math counts as learning to reason.

I was excited about the prospect of learning how the rules of arithmetic worked. Another motivation for taking the course was that I had a four-year-old son who was already showing signs of mathematical genius, and I knew I would soon be called upon to help him with homework. In a 2 Nov. 1967 letter I wrote:

The math course has already been useful in giving me a clearer idea of basic math concepts to help David. That child is incredible. For instance, we had a very interesting discussion at breakfast this morning on relative proportion, and I scarcely had to show him how to divide numbers into unequal proportions, e.g., 2 to 1, then subtract from each in such a way that the proportion remained the same.

I did well in the class. Receiving an A in Structure of Arithmetic was a huge boost to my self-esteem. More confident of my analytical skills, I went on to a satisfying career as a writer, editor and business systems analyst. The four-year-old grew up to be a computer science professor. I recently offered to copy edit the manuscript of his book on computational geometry. Though I didn’t have the skill to check his math, I was pleased that I could follow the logic of his argument. I even found a few typos.