Archive for the ‘feminism’ Category

The persistence of hope

Reading through letters I wrote to my parents in early 1973, I am struck by how much writing I was doing, in spite of all the other stuff going on in my life.

January 10, 1973

(Having been laid off in an economic downturn, my husband was job-hunting.) Nothing new regarding our plans – I wish the thing was settled soon. …

I have been hectically busy for the past month or so. … This week I have been working on an outline of my novel, and polishing up several chapters for a grant-in-aid that is being offered by the San Francisco Foundation. Don’t have much chance of winning it, but less if I don’t enter! … I have a huge pile of papers to grade (my freelance job as a reader for a local high school), for which I shall have to read the textbook first; another reference book on the Indian rock drawings we visited at Tulelake (for an article); and a story to finish on the disposal of Christmas trees for which I have a go-ahead from a local magazine.

February 12, 1973

February 12, 1973

Finished today a short story based on our experience of buying a baby Christmas tree this year. We were going to give it to a park, but the kids wanted to keep it. The kids like the story, so I hope the women’s magazines will.

March 3, 1973

Our own plans are getting more finalized. Tony will be commuting between here and Santa Barbara for a few months … and then we expect to move south when the kids finish school in June. … but at least now I know what sort of time scale I have for finishing up projects here. I am currently working on a big story about the influx of older, traditionally brought up housewives into the women’s movement, and have several other ideas on file that I will need to get material for before we leave, As usual, every new idea spins off into several new stories, and I can’t possibly find time to do them all.

March 22, 1973

Tony leaves for Santa Barbara Monday, and I am going to drive the kids down later in the week for a long weekend of looking around and getting our bearings. … In the meantime I have a huge pile of students’ field trip reports sitting on my desk … and then back to the draft of a story that could be the most important thing that has happened to me career-wise. I have an invitation to submit to Harpers Magazine (and that is the top) a story on the women’s movement. My thesis is that the rapidly increasing numbers of middle-aged, middle-class housewives being attracted to the movement is having a significant effect on the direction of feminist politics. I have been very involved with the setting up of a chapter of National Women’s Political Caucus here, and have also got many insights from the Department of Continuing Education for Women at Foothill College, which is very active in encouraging frustrated housewives to get back into the mainstream of life.

Of course a go-ahead doesn’t mean the story is sold. I think I have learned a lot about this since last year, when I was so crushed that the famous publishing house which wanted to see my novel sent it back again. But still it’s exciting to have it even considered.

Where are they now, all these articles and stories I worked so hard on? Gone. Never published. Not even copies crammed into my old black filing cabinet. I must have thrown them out in a fit of tidiness, or more likely despair. I can’t even find the kind, hand-written rejection letter from the editor of the famous publishing house, which I know I kept for years. All that’s left is the memory of how hopefully we writers begin new projects again and again and again.

Rumblings in the socialist paradise

I sold this early 1970s article about feminism in New Zealand to a US magazine. Unfortunately, the journal folded just after I’d received the galley proofs. Disappointing, but hey, these things happen. Reading the galleys again, I recognize many of my own frustrations, and understand a little better why I had to leave. I realize, of course, that New Zealand society today is very different from what it was then.

Letter From New Zealand

In New Zealand we say it is the land that shapes the people.

The land is lovely, but aloof; it has not welcomed intruders. For a few square miles the forest and scrub have given way, but the houses sit impermanent as boxes on the clearings, and in the towns the raw suburbs perch in self-conscious rows.

Europeans have been here for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain they brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. Together these two strands wove a welfare state that, in providing an economic floor beneath which no family can fall, has codified the disparities between the sexes, and underlined the definition of woman as housewife.

In the 1930s and ‘40s the pattern of social experiment these pioneers began reached its flowering in a social security system that offered a minimum wage, compulsory arbitration of wage disputes, pensions for invalids and deserted wives, family allowances that can be capitalized into housing down payments, low interest housing loans, low rent state houses, and a national health service that provides free medicines and medical treatment. A school dental service provides free dental care for all children. Most recently, in April 1974, an accident compensation scheme went into effect that covers everyone on New Zealand soil, whether earning money or not.

It is a complacently comfortable floor. But at its foundation is the assumption that the only proper place for a woman is in the home taking care of the children.

The welfare of the child is the prevailing argument. Says Norman King, New Zealand Minister of Social Welfare: “The majority feel that a close relationship with its own mother is the birthright of the New Zealand child. We do not want to encourage the adoption of a lifestyle in New Zealand where it becomes normal for the care of very young children to be a specialist task carried out by trained staff in group situations away from the family.”

New Zealand women achieved the right to vote in 1893, second only to Wyoming. Otago University in N.Z. admitted women to degree courses in 1871, the first in the British Empire. There are today very few women Members of Parliament, and no women at all in the administrative levels of higher education. Those who have reached positions of authority in any field are regarded as exceptions to the norm. And in a country as small as New Zealand, to be different is to be disapproved. A friend who returned home after ten years in London says: “Everything in New Zealand presses on me to settle down, to conform, to live safely, not to take risks.” My elder sister, Evelyn Stokes, has a doctorate in geography from an American university. Hostile vibrations still echo in our family over her decision to place her two children in a day care nursery so she could continue her university teaching.

Official thinking assumes that a mother who goes out to work does so either from economic necessity or from disproportionate greed. The idea that women might have talents other than domestic comes hard to New Zealanders. It is certainly not fostered by our education system, which from the start locks children into rigid sex role definitions.

From six-year-old Donald, Evelyn Stokes’s son, comes a crumpled school paper.

Check what toys girls like, he is instructed.

Big and little dolls? Yes, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A train? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A football? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

At the high school level the curriculum encourages vocational discrimination by sex: academic girls are steered towards the arts rather than the sciences, and average girls towards secretarial or home-craft courses.

But the winds of rebellion, fanned by global news services and travelers’ tales, are stirring the curtains at the kitchen windows. Women are staying at school longer and leaving with higher educational qualifications than ten years ago. The percentages of women and of married women in the work force are still lower than most western countries. But their numbers are increasing steadily, despite recent changes in the family benefit structure aimed at dissuading mothers from going out to work. Equal pay recently became law, and will be at least nominally applicable to all areas of the workforce by 1978.

Social custom compounds the problems of those married women who do go out to work.

Pat Brown has her own advertising agency. She told me that a company party with her husband, chief chemist at a freezing works, she attempted to discuss with his colleagues the implications of advertising and the sale of meat. Her husband’s boss took her firmly by the hand and led her to the far side of the room, where the other wives were discussing babies and knitting patterns. “This is your place,” he said.

Domestic duties are another stumbling block. Marriage counselor Marianne Thorpe says: “The difficulty is that women feel that they are responsible for the care of the home and children (and they get almost no help in this task), and this makes working outside the home a complicated business.” Evelyn Stokes and her husband Brian, head of math at a teachers’ college, share responsibility for housework and child care. It is an unusual set-up for a New Zealand family. More typical is Ray Lealand, now retired after a double career of clerical work and home-making, who says: “The most difficult problem I faced whilst working was non-cooperation from my husband.”

Role demarcation in some families is incredibly rigid. One friend recalls the raised eyebrows in her family when as a young bride she took on the vegetable garden. “That’s the husband’s job,” she was told. “The wife does the flowers.”

Since most women expect to stay home once they have a child, the idea of maternity leave is not widely accepted. When Evelyn Stokes applied for leave for the birth of her second child, the committee set up to look into the matter came back with a regulation that a mother who applies for maternity leave “is required to satisfy the university that her additional family duties are compatible with the continuation of her employment.”

Child care facilities for working mothers are inadequate, and though support for day care centers was a major plank in the ruling Labour Party’s 1972 election platform, its implementation has been whittled down to a subsidy to needy children in existing voluntary centers. Part-time employment coinciding with school hours is widely accepted, but employers will take on mothers of preschoolers only as a last resort, and use the argument of family responsibilities to pin women to the lower scale, “temporary” job classifications.

Sex role definitions still apply in employment. Six occupation groups employ 65% of New Zealand’s working women: clerical, sales, clothing manufacture, teaching, nursing, and domestic service. But there has been some movement into the traditionally male areas of drafting, electronics, and electrical work, and into the newer technological jobs like computer programming or systems analysis, where sex-exclusive traditions have not yet calcified. With a shortage of male labor in many fields, a few pioneers are braving the public ridicule and breaking down job opportunity barriers. One such incident, in 1972, even rated media coverage. Two girls applied for jobs in an Auckland factory as aluminum glaziers, only to be told this was not a woman’s job. When they asked “Why not?’ no answer could be found, and they were taken on.

This thread of social change is closely woven with another that is a constant in New Zealand life. Few in numbers, and isolated by thousands of miles from the sources of our culture, we have been almost pathologically dependent on the word from the outside world. I remember my first beat as a cub reporter; I scurried round the tourist hotels of Christchurch, winkling out startled visitors and begging them to express an opinion. Any opinion. Still the pattern continues. Articulate voices from abroad, no matter what their status, receive far more attention than local expects on the same subject.

The feminist movement is a case in point. Local groups springing up in the past few years have found a climate of hostility and ridicule. The ideas of American feminists, distorted by distance and by different cultural norms, have seemed to many to be irrelevant to the New Zealand experience. Then early in 1973 two visitors coincided: Evelyn Reed, an American Marxist feminist who advocated abortion law reform and improved child care facilities, and Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist know for his work on the deleterious effects of maternal deprivation on a child’s mental health. Both, basking in the aura of the magic words “from overseas,” were taken seriously by the local press. Margot Roth, editor of the Journal of the N.Z. Society for Research on Women, comments that the resulting controversy opened up a much wider range than usual of questions concerning women, and helped lay the foundation for the success of a United Women’s Convention held September 1973 in Auckland to mark the 80th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

The purpose of the convention, according to the organizers, was to correct the distorted view New Zealand women had of modern feminism, to raise the status and self-confidence of women, and to increase the numbers of women willing to work on behalf of women’s issues.

Statistics indicate that the fifteen hundred women who attended, while better educated and more likely to be employed than the average, nevertheless made up a remarkably accurate cross-section of New Zealand society. The issues discussed were those that concern women everywhere: job opportunities, control of their bodies, marriage and child care, sex stereotyping.

Press reportage of the Convention again sought to trivialize and ridicule. Afternoon TV revealed to local mums some of the hogwash poured down the verbal ducts at the United Women’s Convention, reported one city daily.

However, rage over press flippancy reinforced a feeling of unity at the conference, and the consensus of those who attended is that, for the first time, women from the whole range of backgrounds and interests in New Zealand life experienced a feeling of sisterhood.

The floodgates are open. Women with common interests are pooling resources. The prestigious National Council of Women, umbrella for all women’s organizations in New Zealand, and for long a stronghold of the traditional view, is now espousing the cause of equality and encouraging its affiliated groups to contribute.

It is hard to say what the future will hold. Though New Zealanders travel the world as casually as migrating godwits, jet planes cannot eliminate the sense of lonely isolation that makes us belittle our homegrown prophets. The land still broods, raw, stubborn, and the people it has bred still revere the sheep shearer above the artist. On embroidered tablecloths, housewives still set teas of cream cakes and scones, and rows of preserves still gleam on pantry shelves.

But the women of New Zealand have a stubborn streak too. Diffident, shy, self-conscious in proclaiming the ideas that come from an almost alien American culture, we are nevertheless gathering strength. The spirit that made New Zealand one of the most comfortable societies in the world may yet take a mattock to the scrublands of tradition, and graze the new fields of equality.

Women’s rights moves into politics

Continuing my exploration of feminism in the 1970s, a profile for my New Zealand newspaper of a woman political candidate.

Women in Politics Part II

Women’s rights moves into politics

Cupertino, CA, October 1972

Rhoda Freier is a new phenomenon in American politics. She is an avowed feminist who has carried the banner of the women’s movement out of the rap sessions and the action groups, and into the male-dominated arena of party politics. As the Democratic Party candidate for the 22nd California Assembly District, her platform is environmental protection and zero population growth.

Until seven years ago Rhoda Freier’s life reflected the malaise of many an American housewife whose children are gone off to school, leaving her with time on her hands. Then the Freiers moved to California. Suddenly all her latent dissatisfactions burst into full bloom. “California does that to people,” she says. Maybe it’s something in the air!”She went back to college to continue her studies in biology and to upgrade her teaching qualification. Her biology studies led her next to Zero Population Growth. Environmental and population concerns began to coalesce into women’s problems.

National Organization for Women (NOW) was the culmination of all these interests and the one which has commanded her strongest loyalties. She became president of the South San Francisco Bay chapter two years ago. As the mainstream of the women’s movement moved toward politics as the only effective method of achieving equality for women, it pushed her along with it.

Diffident and unwilling at first, she surprised herself by winning the three-way race for the Democratic nomination for 22nd District with a handsome 50 percent of the votes. The general election next month is going to be a more difficult proposition. “No matter how strongly you feel about an issue, you have to know how to go about it, and I really didn’t.” Her neophyte campaign organization functions on “a crisis to crisis basis.” Like most candidates, she directs the emphasis herself, with help from consultants within the Democratic Party. It is a strongly woman-centered effort, drawing heavily from NOW and ZPG. Her financial director is a busy young woman with a pre-school family and a part-time job as a children’s librarian, who has still found time to organize events like the jumbo-sized garage sale which netted a whopping $600 for the campaign coffers.

But by no means is it a female chauvinist affair. Ms Freier’s husband is her campaign manager. Paul Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb, has taken time to speak on her behalf. Promises of help in the crucial pre-election work have come from prominent and experienced male members of the local Democratic Party.

Lack of funds is a chronic problem. Democrats, lacking the big business resources of the Republican Party, have traditionally relied heavily on union support. This in Ms Freier’s case has been conspicuously lacking, partly through her own inexperience, and partly through union opposition to the women’s Equal Rights Amendment, which she supports.

The attitude of the local press, who consistently refer to her as “the Women’s Lib candidate,” has also been an obstacle. “I have no qualms about being identified as a feminist. But the term ‘lib’ or ‘libber’ is used in a denigrating way that is very damaging and insulting.”

She doesn’t feel that being a woman is all that much of a handicap. But neither is it a conspicuous asset. A survey by the National Women’s Political Caucus showed that, of thirty new women candidates in the June primary election, only twelve are still in the race, and only two of these, including Rhoda Freier, won contested primaries.

“It’s hard to know what the factors were: unwillingness to vote for a woman; inexperience on the part of the woman running; lack of money? We’ll never know. But I’m certainly not doing what I did initially, which was to point out that we haven’t even reached the level of tokenism in the number of women in the legislature. Some people may be concerned about this, but the vast majority clearly aren’t.” Nowadays I tackle the positive aspects of my candidacy rather than the fact that I am a woman. I have tried to promote myself as a candidate who is more knowledgeable than most of the other legislators in environmental matters and in the need for population stabilization.”

But she does feel that her candidacy will have an impact on the image of women. “The fact of a woman coming forward as a women’s candidate opens new avenues of thought to a whole lot of people.”

POSTSCRIPT: Rhoda Freier lost the election to the Republican incumbent Assemblyman Richard Hayden, but went on to help establish a Bay Area chapter of the nonpartisan National Women’s Political Caucus.

Political women in the 1970s

In early 1972 I had a note from the women’s editor of my New Zealand newspaper requesting pieces on how the women’s liberation movement had changed the role of women in politics. “Surely,” she said, “women over there do more than make tea for the candidates.” My response was a two-part series. First, the attitudes and roles of party workers in my county, now more widely known at Silicon Valley. In my next post, I’ll share a profile of a woman political candidate.

Women in Politics Part I:

Party workers reflect range of attitudes

Santa Clara County, CA, 1972

The grey-haired woman in the Republican campaign trailer sniffed contemptuously. “Women’s lib! I don’t hold with all that stuff.” She is the wife of a retired army officer, and a veteran of political campaigns. Meanwhile, the Republican incumbent for her Assembly district is being challenged by a feminist woman Democrat, and in Southern California the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party is seeking to abolish itself, on the grounds that a separate women’s organization is sexist in conception.

These are the extremes in the spectrum of views on women’s place in the world that the political party workers of Santa Clara County, CA reflect in their organization, their activities, and their attitudes.

Organization at the state level is set for both parties by the state code. Each legislator or party candidate has up to five nominees to the State Central Committee of his party, of whom at least two must be women. From this 1,000-strong body, a man and a woman for each Congressional District are chosen to form the decision-making executive committee.

“The women have a great deal of influence,” says Loretta Riddle, field representative and campaign coordinator for State Senator A. Alquist, who has served on the executive committee for ten years. “It has been a very fair thing. If you have the ability, and work hard, you can make your voice heard.”

The presence of a few women is customary, though not mandatory, on the elected County Central Committees. But at this level the loose structure imposed by the state gives way to local idiosyncrasies. The Democratic Party, though overwhelmingly the majority part of the county, admits to being fragmented and disorganized. The Republicans, on the other hand, pride themselves on their efficiently centralized hierarchy. Robert Walker, executive director of the Republican county headquarters, has the county committee divided into specialized sub-committees, and keeps close liaison with his party’s many volunteer clubs.

In contrast to the 600 members that the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party can muster, the thirteen chapters of Republican Women’s Club in the county have a total of 3,000 members. Ten of the clubs run their own local campaign headquarters, registering voters and handing out literature for all the Republican candidates. They are also the labor force of the campaign. “Those women are fantastic,” says Mr. Walker. “I can send them a 30,000-piece mailing and get it back the next day all ready to go.”

The Democratic women have a project too: they run the county headquarters for the party. Madge Overhouse, its director, feels that she has a strong voice in the running of the party organization. “But it is simply by going ahead and doing something like this. Within the Democratic Party you can come up with an idea and follow it through.”

“Individual effort” is an idea often expressed by Democratic women; “femininity” comes more often to the lips of Republicans. The northern chapter of the Democratic Women’s Division, though less militantly feminist than its counterpart in Southern California, puts most of its fund-raising effort into the campaigns of women candidates. Ladies’ club activities like luncheons or fashion shows, favorites of the Republican women, are not popular with Democrats. “We are more issue-oriented,” says Madge Overhouse.

The advantage of clubs, thinks Robert Walker, is that they attract people who would not ordinarily be involved with the party. He described the Republican Party as “the party of the middle class. They tend to be socially oriented, and this carries over to their approach to doing political work. They want to gain some prestige out of it.”

Joan Menagh was a founder of the Republican Women’s Club in her neighborhood. While enjoying the social aspects, she stresses that education is its primary purpose. “Volunteerism” has been a popular topic for speakers. Traditional social values prevail. Though she has worked up to a seat on the County Central Committee, and a full-time job in the office of U.S. Congressman Ch. Gubser, Mrs Menagh claims to have no political ambitions. “In my life my husband and family come before any of my other activities.”

Democrat Madge Overhouse is also critical of the more militant factions of her party. “We have to recognize that there are a good many women who are perfectly happy to be wives and mothers. The militants are cutting these women off, and I think it’s too bad.”

Nor for that matter will Loretta Riddle run for office, partly because she wants to stay close to her two teenagers, but mainly because her personality is satisfied with the considerable power she already wields behind the scenes. She does however admire women who have aspirations to high office, and is longing to see a woman in the California Senate. “I don’t think men realize how much they need women in politics. Women have a certain sensitivity and perspective that men do not.”

Both Republicans and Democrats see a trend toward more women in public office. “I think it goes back to this whole women’s lib thing,” says Republican Joan Menagh. “Women for many years didn’t feel that running for public office was a particularly feminine thing to do, and voters in the past didn’t feel that a woman could hold her own within the political arena as a candidate. Both ideas are passing.”

Democrat Loretta Riddle agrees. “People have not yet learned to accept women who are forceful. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t go ahead, because then we may go along and start learning little by little.”

The way is open for a woman to rise as high in politics as her ability, tenacity and sheer personal drive will allow. It is a difficult path though, and few are willing to take it. The vast majority of women in political campaigns will no doubt continue to stuff envelopes, sit at voter registration booths, check precinct lists, and make tea for the parched throats of campaign speakers.

Education for perspective transformation

I’ve rummaged through my old black filing cabinet to no avail; I can’t find the draft of my early 1970s interview with Georgia Meredith, director of the re-entry program for women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, CA. I liked Georgia, a warm, caring person who made every woman she met feel welcome in her college program.

Jack Mezirow with his wife Edee, whose return to college in middle age helped spark his theory of transformative learning.

I scoured the Internet, and found one reference to her, in the acknowledgments for a 1978 academic paper on the phenomenon of mid-life women returning to school. The author is Jack Mezirow, who was a professor of adult education and director, Center for Adult Education, Teachers College, Columbia University. Georgia Meredith’s Foothill College program was part of his nation-wide study of re-entry programs for women in community colleges.

Older women on college campuses were a new phenomenon in the early 1970s. Mezirow’s data show that the number of women aged 25–34 attending college rose more than 100 percent from 1970 to 1975. According to his obituary (he died in 2014) Mezirow’s interest was party inspired by watching his wife return to graduate school in middle age.

His research project’s primary thrust was “to identify factors that characteristically impede or facilitate the progress of these re-entry programs.” His findings led to the theory of perspective transformation, which Mezirow describes as “a critical dimension of learning in adulthood that enables us to recognize and reassess the structure of assumptions and expectations which frame our thinking, feeling and acting.” He writes:

“For a perspective transformation to occur, a painful reappraisal of our current perspective must be thrust upon us. Among the re-entry women whom we interviewed, the disturbing event was often external in origin —the death of a husband, a divorce, the loss of a job, a change of city of residence, retirement, an empty nest, a remarriage, the near fatal accident of an only child, or jealousy of a friend who had launched a new career successfully. These disorienting dilemmas of adulthood can dissociate one from long-established modes of living and bring into sharp focus questions of identity, of the meaning and direction of one’s life.”

He lays out ten steps in the transformation cycle:

- A disorienting dilemma;

- Self-examination with feelings of guilt or shame;

- A critical assessment of sex-role assumptions and a sense of alienation from taken-for-granted social roles and expectations;

- Recognition that one’s discontent and the process of transformation are shared and that others have negotiated a similar change;

- Exploring options for new ways of living;

- Building competence and self-confidence in new roles;

- Planning a course of action and acquiring knowledge and skills for implementing one’s plans;

- Provisional efforts to try new roles;

- Building of competence and self-confidence in new roles and relationships; and

- A reintegration into one’s life on the basis of conditions dictated by the new perspective.

Mezirow notes that the scope of re-entry programs expanded as the need to focus on self-exploration, career development and personal growth grew increasingly apparent. Some community colleges needed to make changes in entrance requirements. In many classes, writing based on personal experience was accepted in lieu of academic knowledge of a subject. Cohorts of adult students were kept together to encourage mutual support and encouragement. Classes were often scheduled into blocks of time that fitted with children’s school time. Colleges set up child care facilities, drop-in women’s centers, resource referrals.

“All of the programs,” says Mezirow, “are clearly aware that they exist to provide specialized support for women who are effecting a transition in their lives. Since the women are at different phases in this transitional process, their needs vary. … The central goal …is perspective transformation —helping women to see themselves and their relationships in new ways, which require taking responsibility for their lives, examining their options, and formulating new life plans. It is a unique mission in higher education.”

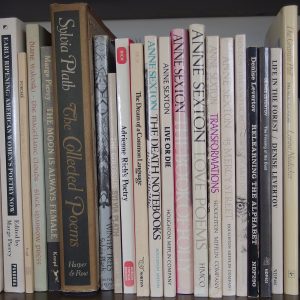

A Language to Hear Myself

I started writing poetry in the fall of 1968. I know the date because that was the year my elder son started kindergarten and his two-year-old brother still took afternoon naps, so I had one hour to myself for the first time in five years. I chose poetry partly because it was a short form. An hour would be time, I figured, to write a line or two, or polish an image.

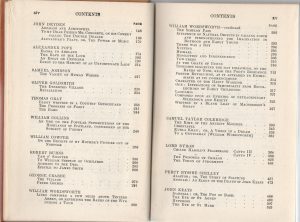

To write well, one needs also to read. I looked around for models. Educated in New Zealand, I had little acquaintance with American poets, and even less with work by women. (The table of contents for my college English I poetry anthology, The English Parnassus (Dixon and Grierson: Oxford 1909), contains no female names.) However, by 1968 I was already becoming acquainted with feminist ideas and literature, such as Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Over the next few years, I sought out female poets.

Anne Sexton’s work immediately caught my attention. Never before had I read poems so uninhibited in their exploration of female sexuality, mental illness, and the constraints of a conventional domestic life. I was particularly excited by Transformations, Sexton’s retelling of well-known tales by the brothers Grimm. Here’s the last stanza of “Cinderella:”

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

Sexton’s retellings bring out the essential unfairness of the old stories’ patriarchal viewpoint. Remember “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” in which an old soldier, having found out the secret of the princesses’ worn dancing shoes, gets to marry his choice of the young women? Here’s Sexton’s wedding scene:

…the princesses averted their eyes

and sagged like old sweatshirts.

Now the runaways would run no more and never

again would their hair be tangled into diamonds,

never again their shoes worn down to a laugh …

Another poet whose books are well represented on my shelves is Denise Levertov. As well as being a beautiful nature poet, she was a passionate protester of the Viet Nam war. This from “The Distance:”

While we are carried to the bus and off to jail to be ‘processed,’

over there the torn-off legs and arms of the living

hang in burnt trees and on broken walls

She also wrote of domestic tasks, such as in this opening stanza of a poem about a visit to her aging mother:

Milk to be boiled

egg to be poached

pot to be scoured.

Many other books by women poets of that era still grace my shelves: Audre Lorde, Sylvia Plath, Marge Piercy, Adrienne Rich, Diane Wakoski, to name a few. A recent exhibition of early feminist poets in the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library collection takes its title from a stanza of the poem “Tear Gas” (1969) by Rich:

I need a language to hear myself with

to see myself in

a language like pigment released on the board

blood-black, sexual green, reds

veined with contradictions

The exhibition’s introductory text by Audre Lorde sums up how I felt as I discovered the feminist poets of the 1960s and ‘70s:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is the vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we give name to the nameless so it can be thought.

Liberation by Strobe Light

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

At the opening forum, my friend Judi and I recognize a few women we know. There is a feeling of bonhomie among the attendees, I have written in my notes. After the introduction we are shown a women’s lib segment from the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family”. Women roar with approval at Gloria’s feminist attitudes, chatter noisily during commercials.

The surroundings for my first breakout session are inauspicious. Out of the rain and into a Foothill College classroom plod two dozen women like myself, suburban housewives, thirtyish to middle-aged, dripping umbrellas. The desks have been pushed back against the cream-colored walls, and the chalkboards are still scribbled with students’ assignments. Self-consciously we obey the call to take off our shoes and sit on the floor. The instructor, in powder blue leotards, is already making pumping movements with her arms.

In formal dancing, she explains, the woman is led by her male partner. But today’s kids dance apart, doing their own thing. We are going to pretend like we are kids. We heave up our sagging muscles. The lights go out. The music comes on, a strong rock beat. A strobe light flickers. I have never seen a strobe before. I am fascinated by the jumping shadows. Impossible to see any other person clearly. The classroom is disappearing, and we are no-place. Though we are crowded together, we are each alone, in our own darkness. At first we copy the movements of the instructor, but imperceptibly private fantasy takes over.

From my mother I learned to fear my sexuality. Now I am doing a sexy dance, gyrating my body in a collage of distant memories. I see again the smoky crush of teenage bodies glimpsed through a basement doorway at a country club near Syracuse, NY. It was 1962; the Twist was just coming in. Terrifying, beautiful, and my fear was mixed with envy of these kids little younger than myself, who could accept their bodies’ needs and express them freely.

My fingers flicker in the strobe light, twenty fingers instead of ten, flying over the keyboard of an imaginary concert grand. I am strong. I am ambitious. I am free. The beat of the music rises to a climax. My body is soaring to a rhythm of its own. I have flown back fourteen years, back to Syracuse, NY, back to the doorway of the smoky basement. I enter the door and mingle with the grease and sweat of the dancers. I am no longer afraid. The tape ends, the lights come on, and we flop exhausted onto the schoolroom floor.

My next workshop is titled “Changing Images.” A large wood-floored room in a gymnasium complex, walled with mirrors at both ends. Again we take our shoes off, and lie on the floor to do a relaxation exercise. “Breathe … out. Now let’s see what happens when we loosen our clothes. Those of us that have belts on, let’s undo them. Let’s unbutton our slacks. There now, isn’t that more comfortable?” We are given a little pep talk on the influence of other people on our fashion choices, then break up into small groups to discuss how we feel about our clothes. I tell about my conservative wool suit, and how mod and worldly and competent I felt when I dressed it up with cream opaque pantyhose and body-shirt to go out and do an interview. A striking single girl confesses that she usually winds up wearing a sexy dress to go to a party where there may be new men. A matron in trim blue slacks and floral shirt tells how she automatically thought of wearing a knit suit to this workshop, until she read in the paper the invitation to wear “comfortable” clothes. She wishes she could find her own style – everything she buys turns out to be too conservative for what she thinks may be the real her, yet very suitable for her role as wife and mother, church-goer, active member of the PTA at her kids’ school. We try on a few wigs and clothes. It’s fun, but inconclusive – there are not enough things to do much with.

I meet Judi at the cafeteria for lunch, and we trade notes. At her clothing workshop, the first of her day, two women had stood conspicuously at the side, refusing to soil their clothes by lying on the floor. Everyone now is very chummy. The cafeteria is crowded. I hadn’t realized there were so many women here. The luncheon speaker gives a brief potted history of the women’s movement. Her voice is rather flat, and I have read it all before anyway. I look at the mural from the morning’s painting session. It is very militant. I look for the positive, affirmative images. Not many. In a flash I know what I want to paint.

My last workshop of the long, full day is a painting session. In theory, we are to paint our reaction to the clip we were shown of the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family,” in which Archie’s wife Gloria expresses feminist attitudes and Archie berates her. But that was early this morning, at the introductory forum. A lot has happened since then.

Most women paint their reactions to the day. One painting is of a huge orange cloud, turbulent, stormy, but beautiful, and raining golden rain onto a green hillside. This was how she saw what was happening today, says the painter. The stirring of new ideas was exciting, but also scary, and in the long run it would benefit humankind.

Many women paint themselves. “This is me when I can’t cope,” writes a mother from a wealthy suburb, whose dark green and black picture shows a figure in bed under the covers, surrounded by black smoke and scary faces. Another draws a bright fire arched over by a brown form. “The brown shape is her man,” says the painter. He is both protecting her from the outside world, and smothering her fire so it can’t get out.

My image comes out fast, so fast I keep running out of paint on my brush. I draw the arms first, in dark, strong red, reaching up, hands wide open. A smiling face, a body, a quick angle of a dress to show that she is female. “Reach out!” I shout in red paint underneath. Then quickly back to the table to find some yellow paint. Bright yellow light scribbles itself behind the figure. She looks too sketchy. Pour the yellow paint into a remnant of blue to give her a green dress. Green hair? Why not? “This is where I am at,” I tell my fellow painters. “I have broken out of my chains.”

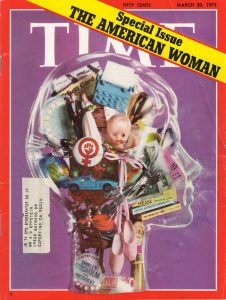

Time Magazine on women, 1972

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

The issue starts, as usual, with letters to the editor. These are from female readers responding to the magazine’s invitation to “write to us about their experiences and attitudes as women, and to tell us how their views on this subject have changed in recent years.” I tabulate the responses. Twenty enthusiastic about the new feminism, three ambivalent, and six tending negative, arguing that, since very few higher level jobs are available to women, by going out to work they “trade the drudgery of housewifery for the drudgery of an office job.” Or, as another writer put it: “Rush out each day to that exhilarating, high-paid position; rush home to that hot-cooked supper (cooked by whom?); relax in that nice clean living room (cleaned by whom?). Most likely, dearie, you’ll hold down two jobs—‘cause when you get home from that executive job in the sky, there ain’t gonna be no unliberated woman left (and certainly no man) to do your grub work.” Sidebars titled “Situation Report” in the various sections of the issue reflect these caveats: prejudice is rampant against allowing women into higher paid or managerial professions.

Time’s editorial attempts to define “the New Feminism” as “… a state of mind that has raised serious questions about the way people live—about their families, homes, child rearing, jobs, governments and the nature of the sexes themselves. Or so it seems now. Some of those who have weathered the torrential fads of the last decade wonder if the New Woman’s movement may not be merely another sociological entertainment that will subside presently.”

Subsequent pages offer a history of the currents of social change that “have converged the make the New Feminism an idea whose time has come.” There are portraits of a range of American women, a piece on “the organizations, aims, difficulties and range of opinions that help make up Women’s Liberation in all its diverse forms,” a one-page snapshot of attitudes in Red Oak, a small Iowa town. Here’s a quote: “Many Red Oak women agree with Doctor’s Wife Jane Smith: ‘A woman’s place is in the home taking care of her children. If a woman gets bored with the housework, there are plenty of organizations she can join.’” A photograph shows Mrs. Smith entertaining friends at bridge. I have a flash of memory: one of my sisters saying the same words to me.

The “Politics” section of the magazine showcases some familiar names: Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, Martha Mitchell, and describes the bipartisan effort of the National Women’s Political Caucus to get more women elected, or selected, as delegates to the Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

The “Science” section describes the difficulties a woman astronomer faced. As a woman Margaret Burbidge, who helped develop a new explanation of how elements are formed in the stars, “found that she could get precious observing time at Mount Wilson Observatory only if her husband [a physicist] applied for it and she pretended to act as his assistant.” The Burbidges also ran into nepotism rules at the University of Chicago. “’The irony of such rules,’ says Mrs. Burbidge, who had to settled for an unsalaried appointment while her husband was named a fully paid associate professor, ‘is that they are always used against the wife.’” I think of women scientists I have known who suffered the same exclusion, such as Beatrice Tinsley, a British-born New Zealand astronomer and cosmologist whose research made fundamental contributions to the astronomical understanding of how galaxies evolve, grow and die. Beatrice had to divorce her husband, a Texas University professor, and move to Yale to gain the position she needed to do her work.

In many science fields, recognition for outstanding women is still abysmally low. I think of efforts by my son David, a mathematician, to redress the paucity of profiles of eminent women mathematicians in Wikipedia.

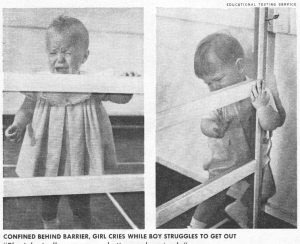

Section after section, the stories continue. “The Press” section is subtitled “Fight from Fluff,” how women’s pages are shifting to more general interest features. ”Modern Living” talks about efforts to find new pronouns, the opening of day care centers, and changes in marriage dynamics. The Situation Report for the “Law” section puts the number of women lawyers in the U.S. at 9000, 2.8% of the total number of lawyers. Of this small number, “less than 12% of them were making more than $20,000, as compared to 50% of the men.” Similarly depressing are statistics for recognition of women in the arts, in business, and in medicine. The “Behavior” section, which looks at research into sex-related differences in early childhood, seems to reinforce stereotypes: “Many researchers have found greater dependence and docility in very young girls, greater autonomy and activity in boys.” The accompanying pictures show two babies behind a barrier set up to separate them from their mothers. The little girl cries helplessly; the boy struggles to get out.

A keynote essay by Sue Kaufman, author of the novel Diary of a Mad Housewife, attempts to capture the feelings of a composite American woman, interested in the new ideas, admiring of feminist leaders, but cautious about jumping on the bandwagon. Kaufman describes an imagined scene: an admired leader is coming to town to speak. The woman arranges for a babysitter. “She will go, usually with friends. They will arrive … take their seats—and slowly it will begin to happen … she begins to feel the flickers and currents of a mass communion, a rising sense of excitement that she imagines parallels what one feels at a revival meeting … this powerful thing happening, this sweeping, surging, gathering-up-momentum feeling of intense camaraderie, solidarity movement.” After the meeting is over, Kaufman describes the woman driving home, paying the sitter, returning to the children and the kitchen “to take up the reins of her existence. Only—something is wrong. She is overwhelmed by a terrible sense of wrongness, of jarring inconsistency. There was that surging, powerful feeling in the hall, and now, stranded on the linoleum under the battery of fluorescent kitchen lights, there is this terrible sense of isolation, of walls closing in, of being trapped. …but she doesn’t burst into tears. …In spite of the desolation she feels, she knows that she is not alone…there is enormous comfort in knowing that. And knowing that is one of the big changes in her life.”