Archive for the ‘politics’ Category

The other side of the freeway

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a battered cardboard box containing the manuscript of a novel I wrote in the early 1970s. I understand now why it never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject: racial discrimination in housing. As I reread some of the text, I recalled the shock I felt when I first grasped the magnitude of the social gaps. The descriptions that follow come from my own experience as I researched the book, and it began my involvement with the fair housing movement.

Here is the central character Karen, a newspaper reporter, visiting the black ghetto of East Palo Alto for the first time to interview the director of a community advice center:

She knew vaguely that East Palo Alto belonged to the county. … She crossed the county line now, and accelerated to get onto the overpass that spanned the freeway. As she came down the ramp on the other side, she knew she was in a different country. The road was suddenly pot-holed and bumpy, and brown dust rose in thick choking swirls from its verges. She slowed, and looked about her. Such tiny bedraggled houses, desperately in need of paint. Yards littered with junk, yet here and there a brave attempt at order and color, a flower-bed, a well-cut lawn. She came upon a few tatty shops. Surely this couldn’t be the main shopping center? Yet soon she could see the sign, NAIROBI SHOPPING CENTER, and underneath, in a language she could not understand, UHURU NA UMOJA.

She had to force herself to open the door. Lurid accounts of rapes and muggings and violence in the streets flooded her mind. Here she was the enemy. She wanted to jump back into the car and get out, away from this place.

A woman passed, with two small children, headed for the market. She looked indifferently at Karen as she passed, then turned to scold one of the children, who was whining for candy. Karen let out the breath she had been involuntarily holding, and made herself move on. … Across the road, outside a liquor store, a black knot of middle-aged men stood transfixed in time, waiting for nothing.

It was hot. The dust lifted lazily as she walked. Something about the huge trees, and the stillness of the air, brought to her mind descriptions she had read of towns in the southern states. But this was California. It did not make sense. A mockingbird flashed its wings across her path, still proudly singing.

Karen does her interview, in which she learns about the pressures of living in East Palo Alto (and also finds herself attracted to Paul, the advice center director).

She said goodbye, and walked slowly back to the car, past the Louisiana Soul Food Kitchen and the Black and Tan Barber. The heat and dust were almost unbearable.

Back across the freeway, she noticed for the first time the neatly swinging redwood sign: Welcome to Palo Alto. A few blocks further down University Avenue and it hit her like a punch in the gut. She pulled over to the side of the road and rested her head on the steering wheel, fighting back an impulse to vomit. The contrast was an obscenity. Huge magnolias here lined the street on both sides, giving deep dappled shade to the well-paved highway. Between the road and the white concrete sidewalks rose great greening mounds of juniper and ivy, and beyond them, with manicured lawns and discreet sprinkler systems, were the complacent mansions of the rich.

Rumblings in the socialist paradise

I sold this early 1970s article about feminism in New Zealand to a US magazine. Unfortunately, the journal folded just after I’d received the galley proofs. Disappointing, but hey, these things happen. Reading the galleys again, I recognize many of my own frustrations, and understand a little better why I had to leave. I realize, of course, that New Zealand society today is very different from what it was then.

Letter From New Zealand

In New Zealand we say it is the land that shapes the people.

The land is lovely, but aloof; it has not welcomed intruders. For a few square miles the forest and scrub have given way, but the houses sit impermanent as boxes on the clearings, and in the towns the raw suburbs perch in self-conscious rows.

Europeans have been here for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain they brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. Together these two strands wove a welfare state that, in providing an economic floor beneath which no family can fall, has codified the disparities between the sexes, and underlined the definition of woman as housewife.

In the 1930s and ‘40s the pattern of social experiment these pioneers began reached its flowering in a social security system that offered a minimum wage, compulsory arbitration of wage disputes, pensions for invalids and deserted wives, family allowances that can be capitalized into housing down payments, low interest housing loans, low rent state houses, and a national health service that provides free medicines and medical treatment. A school dental service provides free dental care for all children. Most recently, in April 1974, an accident compensation scheme went into effect that covers everyone on New Zealand soil, whether earning money or not.

It is a complacently comfortable floor. But at its foundation is the assumption that the only proper place for a woman is in the home taking care of the children.

The welfare of the child is the prevailing argument. Says Norman King, New Zealand Minister of Social Welfare: “The majority feel that a close relationship with its own mother is the birthright of the New Zealand child. We do not want to encourage the adoption of a lifestyle in New Zealand where it becomes normal for the care of very young children to be a specialist task carried out by trained staff in group situations away from the family.”

New Zealand women achieved the right to vote in 1893, second only to Wyoming. Otago University in N.Z. admitted women to degree courses in 1871, the first in the British Empire. There are today very few women Members of Parliament, and no women at all in the administrative levels of higher education. Those who have reached positions of authority in any field are regarded as exceptions to the norm. And in a country as small as New Zealand, to be different is to be disapproved. A friend who returned home after ten years in London says: “Everything in New Zealand presses on me to settle down, to conform, to live safely, not to take risks.” My elder sister, Evelyn Stokes, has a doctorate in geography from an American university. Hostile vibrations still echo in our family over her decision to place her two children in a day care nursery so she could continue her university teaching.

Official thinking assumes that a mother who goes out to work does so either from economic necessity or from disproportionate greed. The idea that women might have talents other than domestic comes hard to New Zealanders. It is certainly not fostered by our education system, which from the start locks children into rigid sex role definitions.

From six-year-old Donald, Evelyn Stokes’s son, comes a crumpled school paper.

Check what toys girls like, he is instructed.

Big and little dolls? Yes, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A train? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A football? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

At the high school level the curriculum encourages vocational discrimination by sex: academic girls are steered towards the arts rather than the sciences, and average girls towards secretarial or home-craft courses.

But the winds of rebellion, fanned by global news services and travelers’ tales, are stirring the curtains at the kitchen windows. Women are staying at school longer and leaving with higher educational qualifications than ten years ago. The percentages of women and of married women in the work force are still lower than most western countries. But their numbers are increasing steadily, despite recent changes in the family benefit structure aimed at dissuading mothers from going out to work. Equal pay recently became law, and will be at least nominally applicable to all areas of the workforce by 1978.

Social custom compounds the problems of those married women who do go out to work.

Pat Brown has her own advertising agency. She told me that a company party with her husband, chief chemist at a freezing works, she attempted to discuss with his colleagues the implications of advertising and the sale of meat. Her husband’s boss took her firmly by the hand and led her to the far side of the room, where the other wives were discussing babies and knitting patterns. “This is your place,” he said.

Domestic duties are another stumbling block. Marriage counselor Marianne Thorpe says: “The difficulty is that women feel that they are responsible for the care of the home and children (and they get almost no help in this task), and this makes working outside the home a complicated business.” Evelyn Stokes and her husband Brian, head of math at a teachers’ college, share responsibility for housework and child care. It is an unusual set-up for a New Zealand family. More typical is Ray Lealand, now retired after a double career of clerical work and home-making, who says: “The most difficult problem I faced whilst working was non-cooperation from my husband.”

Role demarcation in some families is incredibly rigid. One friend recalls the raised eyebrows in her family when as a young bride she took on the vegetable garden. “That’s the husband’s job,” she was told. “The wife does the flowers.”

Since most women expect to stay home once they have a child, the idea of maternity leave is not widely accepted. When Evelyn Stokes applied for leave for the birth of her second child, the committee set up to look into the matter came back with a regulation that a mother who applies for maternity leave “is required to satisfy the university that her additional family duties are compatible with the continuation of her employment.”

Child care facilities for working mothers are inadequate, and though support for day care centers was a major plank in the ruling Labour Party’s 1972 election platform, its implementation has been whittled down to a subsidy to needy children in existing voluntary centers. Part-time employment coinciding with school hours is widely accepted, but employers will take on mothers of preschoolers only as a last resort, and use the argument of family responsibilities to pin women to the lower scale, “temporary” job classifications.

Sex role definitions still apply in employment. Six occupation groups employ 65% of New Zealand’s working women: clerical, sales, clothing manufacture, teaching, nursing, and domestic service. But there has been some movement into the traditionally male areas of drafting, electronics, and electrical work, and into the newer technological jobs like computer programming or systems analysis, where sex-exclusive traditions have not yet calcified. With a shortage of male labor in many fields, a few pioneers are braving the public ridicule and breaking down job opportunity barriers. One such incident, in 1972, even rated media coverage. Two girls applied for jobs in an Auckland factory as aluminum glaziers, only to be told this was not a woman’s job. When they asked “Why not?’ no answer could be found, and they were taken on.

This thread of social change is closely woven with another that is a constant in New Zealand life. Few in numbers, and isolated by thousands of miles from the sources of our culture, we have been almost pathologically dependent on the word from the outside world. I remember my first beat as a cub reporter; I scurried round the tourist hotels of Christchurch, winkling out startled visitors and begging them to express an opinion. Any opinion. Still the pattern continues. Articulate voices from abroad, no matter what their status, receive far more attention than local expects on the same subject.

The feminist movement is a case in point. Local groups springing up in the past few years have found a climate of hostility and ridicule. The ideas of American feminists, distorted by distance and by different cultural norms, have seemed to many to be irrelevant to the New Zealand experience. Then early in 1973 two visitors coincided: Evelyn Reed, an American Marxist feminist who advocated abortion law reform and improved child care facilities, and Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist know for his work on the deleterious effects of maternal deprivation on a child’s mental health. Both, basking in the aura of the magic words “from overseas,” were taken seriously by the local press. Margot Roth, editor of the Journal of the N.Z. Society for Research on Women, comments that the resulting controversy opened up a much wider range than usual of questions concerning women, and helped lay the foundation for the success of a United Women’s Convention held September 1973 in Auckland to mark the 80th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

The purpose of the convention, according to the organizers, was to correct the distorted view New Zealand women had of modern feminism, to raise the status and self-confidence of women, and to increase the numbers of women willing to work on behalf of women’s issues.

Statistics indicate that the fifteen hundred women who attended, while better educated and more likely to be employed than the average, nevertheless made up a remarkably accurate cross-section of New Zealand society. The issues discussed were those that concern women everywhere: job opportunities, control of their bodies, marriage and child care, sex stereotyping.

Press reportage of the Convention again sought to trivialize and ridicule. Afternoon TV revealed to local mums some of the hogwash poured down the verbal ducts at the United Women’s Convention, reported one city daily.

However, rage over press flippancy reinforced a feeling of unity at the conference, and the consensus of those who attended is that, for the first time, women from the whole range of backgrounds and interests in New Zealand life experienced a feeling of sisterhood.

The floodgates are open. Women with common interests are pooling resources. The prestigious National Council of Women, umbrella for all women’s organizations in New Zealand, and for long a stronghold of the traditional view, is now espousing the cause of equality and encouraging its affiliated groups to contribute.

It is hard to say what the future will hold. Though New Zealanders travel the world as casually as migrating godwits, jet planes cannot eliminate the sense of lonely isolation that makes us belittle our homegrown prophets. The land still broods, raw, stubborn, and the people it has bred still revere the sheep shearer above the artist. On embroidered tablecloths, housewives still set teas of cream cakes and scones, and rows of preserves still gleam on pantry shelves.

But the women of New Zealand have a stubborn streak too. Diffident, shy, self-conscious in proclaiming the ideas that come from an almost alien American culture, we are nevertheless gathering strength. The spirit that made New Zealand one of the most comfortable societies in the world may yet take a mattock to the scrublands of tradition, and graze the new fields of equality.

The citizenship decision

In 1972, five years after I emigrated to the US clutching my hard-won Green Card, my official status was Resident Alien. I was required to register at the Post Office every January. If I wanted to leave the country, I had to prove that my income tax payments were up to date. I had to remain “of good moral character” and could be expelled if I had a run-in with the law. And I couldn’t vote.

Meanwhile, opposition to US involvement in Viet Nam was heating up. A turning point for me was the May 1970 killing and wounding of students by members of the National Guard at Kent State University, where students were protesting the secret bombing of Cambodia. As a history major, I already understood why interference in another country’s self-determination was bound to end badly. It was obvious to me as an outsider that the Viet Nam War was a disaster. Yet here in this supposed Land of the Free, it seemed that the authorities were beating up people who said so.

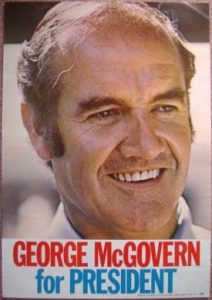

If I couldn’t publicly protest, and I couldn’t vote, at least I could help behind the scenes. I became interested in the anti-war policies of presidential candidate George McGovern, and began to volunteer in his California primary campaign. Here’s how I described my activities in a letter to parents:

June 2, 1972

I have been sticking my neck out in other directions lately too – have become very involved in George McGovern’s presidential campaign. I have put in some time at the campaign headquarters, and then got nailed to organise the local precinct. It is really rather fun, once I got over the initial panic. Support for him is very strong in this area, so I was lucky in the number of people I could con into working for me. Our house is going to be the headquarters for all 30 Cupertino precincts Tuesday (election day), so that should be interesting too. Am meeting all sorts of interesting people, especially the out-of-state students who are travelling around working for him. There are some neat kids amongst them.

McGovern won the nomination, but lost the November election to incumbent Richard Nixon. Meanwhile, I was feeling ambivalent about my own status. After five years in the US, a Resident Alien may commence the application process to become a citizen. Was I ready to do that? Could I turn my back on the land that had nurtured me and my ancestors? Could I pledge allegiance to a country whose foreign incursions I could not support? On the other hand, how badly did I want to share with my neighbors in making decisions about this place we all now called home? For most immigrants, this is a decision that requires careful thought and soul-searching. In the end, my husband and I decided to apply for citizenship. We didn’t know then how many years, frustrations and phone-calls it would take. But that’s another story.

Women’s rights moves into politics

Continuing my exploration of feminism in the 1970s, a profile for my New Zealand newspaper of a woman political candidate.

Women in Politics Part II

Women’s rights moves into politics

Cupertino, CA, October 1972

Rhoda Freier is a new phenomenon in American politics. She is an avowed feminist who has carried the banner of the women’s movement out of the rap sessions and the action groups, and into the male-dominated arena of party politics. As the Democratic Party candidate for the 22nd California Assembly District, her platform is environmental protection and zero population growth.

Until seven years ago Rhoda Freier’s life reflected the malaise of many an American housewife whose children are gone off to school, leaving her with time on her hands. Then the Freiers moved to California. Suddenly all her latent dissatisfactions burst into full bloom. “California does that to people,” she says. Maybe it’s something in the air!”She went back to college to continue her studies in biology and to upgrade her teaching qualification. Her biology studies led her next to Zero Population Growth. Environmental and population concerns began to coalesce into women’s problems.

National Organization for Women (NOW) was the culmination of all these interests and the one which has commanded her strongest loyalties. She became president of the South San Francisco Bay chapter two years ago. As the mainstream of the women’s movement moved toward politics as the only effective method of achieving equality for women, it pushed her along with it.

Diffident and unwilling at first, she surprised herself by winning the three-way race for the Democratic nomination for 22nd District with a handsome 50 percent of the votes. The general election next month is going to be a more difficult proposition. “No matter how strongly you feel about an issue, you have to know how to go about it, and I really didn’t.” Her neophyte campaign organization functions on “a crisis to crisis basis.” Like most candidates, she directs the emphasis herself, with help from consultants within the Democratic Party. It is a strongly woman-centered effort, drawing heavily from NOW and ZPG. Her financial director is a busy young woman with a pre-school family and a part-time job as a children’s librarian, who has still found time to organize events like the jumbo-sized garage sale which netted a whopping $600 for the campaign coffers.

But by no means is it a female chauvinist affair. Ms Freier’s husband is her campaign manager. Paul Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb, has taken time to speak on her behalf. Promises of help in the crucial pre-election work have come from prominent and experienced male members of the local Democratic Party.

Lack of funds is a chronic problem. Democrats, lacking the big business resources of the Republican Party, have traditionally relied heavily on union support. This in Ms Freier’s case has been conspicuously lacking, partly through her own inexperience, and partly through union opposition to the women’s Equal Rights Amendment, which she supports.

The attitude of the local press, who consistently refer to her as “the Women’s Lib candidate,” has also been an obstacle. “I have no qualms about being identified as a feminist. But the term ‘lib’ or ‘libber’ is used in a denigrating way that is very damaging and insulting.”

She doesn’t feel that being a woman is all that much of a handicap. But neither is it a conspicuous asset. A survey by the National Women’s Political Caucus showed that, of thirty new women candidates in the June primary election, only twelve are still in the race, and only two of these, including Rhoda Freier, won contested primaries.

“It’s hard to know what the factors were: unwillingness to vote for a woman; inexperience on the part of the woman running; lack of money? We’ll never know. But I’m certainly not doing what I did initially, which was to point out that we haven’t even reached the level of tokenism in the number of women in the legislature. Some people may be concerned about this, but the vast majority clearly aren’t.” Nowadays I tackle the positive aspects of my candidacy rather than the fact that I am a woman. I have tried to promote myself as a candidate who is more knowledgeable than most of the other legislators in environmental matters and in the need for population stabilization.”

But she does feel that her candidacy will have an impact on the image of women. “The fact of a woman coming forward as a women’s candidate opens new avenues of thought to a whole lot of people.”

POSTSCRIPT: Rhoda Freier lost the election to the Republican incumbent Assemblyman Richard Hayden, but went on to help establish a Bay Area chapter of the nonpartisan National Women’s Political Caucus.

Political women in the 1970s

In early 1972 I had a note from the women’s editor of my New Zealand newspaper requesting pieces on how the women’s liberation movement had changed the role of women in politics. “Surely,” she said, “women over there do more than make tea for the candidates.” My response was a two-part series. First, the attitudes and roles of party workers in my county, now more widely known at Silicon Valley. In my next post, I’ll share a profile of a woman political candidate.

Women in Politics Part I:

Party workers reflect range of attitudes

Santa Clara County, CA, 1972

The grey-haired woman in the Republican campaign trailer sniffed contemptuously. “Women’s lib! I don’t hold with all that stuff.” She is the wife of a retired army officer, and a veteran of political campaigns. Meanwhile, the Republican incumbent for her Assembly district is being challenged by a feminist woman Democrat, and in Southern California the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party is seeking to abolish itself, on the grounds that a separate women’s organization is sexist in conception.

These are the extremes in the spectrum of views on women’s place in the world that the political party workers of Santa Clara County, CA reflect in their organization, their activities, and their attitudes.

Organization at the state level is set for both parties by the state code. Each legislator or party candidate has up to five nominees to the State Central Committee of his party, of whom at least two must be women. From this 1,000-strong body, a man and a woman for each Congressional District are chosen to form the decision-making executive committee.

“The women have a great deal of influence,” says Loretta Riddle, field representative and campaign coordinator for State Senator A. Alquist, who has served on the executive committee for ten years. “It has been a very fair thing. If you have the ability, and work hard, you can make your voice heard.”

The presence of a few women is customary, though not mandatory, on the elected County Central Committees. But at this level the loose structure imposed by the state gives way to local idiosyncrasies. The Democratic Party, though overwhelmingly the majority part of the county, admits to being fragmented and disorganized. The Republicans, on the other hand, pride themselves on their efficiently centralized hierarchy. Robert Walker, executive director of the Republican county headquarters, has the county committee divided into specialized sub-committees, and keeps close liaison with his party’s many volunteer clubs.

In contrast to the 600 members that the Women’s Division of the Democratic Party can muster, the thirteen chapters of Republican Women’s Club in the county have a total of 3,000 members. Ten of the clubs run their own local campaign headquarters, registering voters and handing out literature for all the Republican candidates. They are also the labor force of the campaign. “Those women are fantastic,” says Mr. Walker. “I can send them a 30,000-piece mailing and get it back the next day all ready to go.”

The Democratic women have a project too: they run the county headquarters for the party. Madge Overhouse, its director, feels that she has a strong voice in the running of the party organization. “But it is simply by going ahead and doing something like this. Within the Democratic Party you can come up with an idea and follow it through.”

“Individual effort” is an idea often expressed by Democratic women; “femininity” comes more often to the lips of Republicans. The northern chapter of the Democratic Women’s Division, though less militantly feminist than its counterpart in Southern California, puts most of its fund-raising effort into the campaigns of women candidates. Ladies’ club activities like luncheons or fashion shows, favorites of the Republican women, are not popular with Democrats. “We are more issue-oriented,” says Madge Overhouse.

The advantage of clubs, thinks Robert Walker, is that they attract people who would not ordinarily be involved with the party. He described the Republican Party as “the party of the middle class. They tend to be socially oriented, and this carries over to their approach to doing political work. They want to gain some prestige out of it.”

Joan Menagh was a founder of the Republican Women’s Club in her neighborhood. While enjoying the social aspects, she stresses that education is its primary purpose. “Volunteerism” has been a popular topic for speakers. Traditional social values prevail. Though she has worked up to a seat on the County Central Committee, and a full-time job in the office of U.S. Congressman Ch. Gubser, Mrs Menagh claims to have no political ambitions. “In my life my husband and family come before any of my other activities.”

Democrat Madge Overhouse is also critical of the more militant factions of her party. “We have to recognize that there are a good many women who are perfectly happy to be wives and mothers. The militants are cutting these women off, and I think it’s too bad.”

Nor for that matter will Loretta Riddle run for office, partly because she wants to stay close to her two teenagers, but mainly because her personality is satisfied with the considerable power she already wields behind the scenes. She does however admire women who have aspirations to high office, and is longing to see a woman in the California Senate. “I don’t think men realize how much they need women in politics. Women have a certain sensitivity and perspective that men do not.”

Both Republicans and Democrats see a trend toward more women in public office. “I think it goes back to this whole women’s lib thing,” says Republican Joan Menagh. “Women for many years didn’t feel that running for public office was a particularly feminine thing to do, and voters in the past didn’t feel that a woman could hold her own within the political arena as a candidate. Both ideas are passing.”

Democrat Loretta Riddle agrees. “People have not yet learned to accept women who are forceful. But that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t go ahead, because then we may go along and start learning little by little.”

The way is open for a woman to rise as high in politics as her ability, tenacity and sheer personal drive will allow. It is a difficult path though, and few are willing to take it. The vast majority of women in political campaigns will no doubt continue to stuff envelopes, sit at voter registration booths, check precinct lists, and make tea for the parched throats of campaign speakers.