Archive for the ‘writing’ Category

Looking back at a life

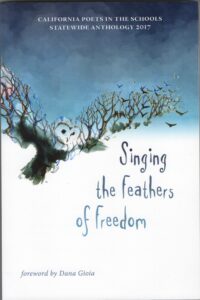

The cover image is a detail from the watercolor painting “Under the Fog” by Mendocino Coast artist Karen Bowers.

So far this blog has been a form of memoir: small stories and reflections about some aspect of my history. Today I break that pattern to tell you about another aspect of my writing life, poetry. I’m excited to announce that my latest collection of poems, Horizon Line, will be published next April by Main Street Rag Publishing Co. The publisher has set up a handsome webpage where you can place pre-publication orders at a substantial discount from the $14 list price.

Horizon Line is also a kind of memoir. The title poem sets the theme of the book: “To limn a life in perspective …” From my house on the Mendocino Coast in Northern California, I watch the sea fog move in and out, changing as it does the viewer’s perception of where the horizon is. I use this variability as a metaphor for what it’s like to look back on my life. Here’s the poem in full:

Horizon Line

To limn a life in perspective

the artist first defines

a horizon line eye level to the viewer.

From my hill of years the horizon

is fluid as in watery, but also

as in unpredictable.

On the sea’s face a wall of fog

moves in and out like histories

remembered and forgotten.

Sometimes silver striates the sea

with such a glitter of insight

I am bedazzled and cannot look.

Sometimes fogbank and ocean

merge with such blue-gray unity

it seems the horizon rises

so that I stand on the shore

dwarfed by a surf of knowledge

that pounds at my ignorance.

Sometimes the sea becomes invisible

the white air a questioning emptiness

a finger-touch of damp against the cheek.

Indigo Moor, Poet Laureate of Sacramento Emeritus, said this about the collection:

In her new poetry collection, Horizon Line, Maureen Eppstein takes an imagistic look at the systole and diastole of the immigrant experience. Divided into four chambers, Horizon Line presents a New Zealand eye’s view of the American experience, from the landing on these shores, through the struggle for spirituality, and, finally, to the unerring clarity of the clearing at the end of the path.

Like a retrospective exhibition of an artist’s work, I see this book as a summing up of my spiritual and artistic journey. I would be honored to have you as one of my readers. Again, here’s the link for ordering Horizon Line:

The persistence of hope

Reading through letters I wrote to my parents in early 1973, I am struck by how much writing I was doing, in spite of all the other stuff going on in my life.

January 10, 1973

(Having been laid off in an economic downturn, my husband was job-hunting.) Nothing new regarding our plans – I wish the thing was settled soon. …

I have been hectically busy for the past month or so. … This week I have been working on an outline of my novel, and polishing up several chapters for a grant-in-aid that is being offered by the San Francisco Foundation. Don’t have much chance of winning it, but less if I don’t enter! … I have a huge pile of papers to grade (my freelance job as a reader for a local high school), for which I shall have to read the textbook first; another reference book on the Indian rock drawings we visited at Tulelake (for an article); and a story to finish on the disposal of Christmas trees for which I have a go-ahead from a local magazine.

February 12, 1973

February 12, 1973

Finished today a short story based on our experience of buying a baby Christmas tree this year. We were going to give it to a park, but the kids wanted to keep it. The kids like the story, so I hope the women’s magazines will.

March 3, 1973

Our own plans are getting more finalized. Tony will be commuting between here and Santa Barbara for a few months … and then we expect to move south when the kids finish school in June. … but at least now I know what sort of time scale I have for finishing up projects here. I am currently working on a big story about the influx of older, traditionally brought up housewives into the women’s movement, and have several other ideas on file that I will need to get material for before we leave, As usual, every new idea spins off into several new stories, and I can’t possibly find time to do them all.

March 22, 1973

Tony leaves for Santa Barbara Monday, and I am going to drive the kids down later in the week for a long weekend of looking around and getting our bearings. … In the meantime I have a huge pile of students’ field trip reports sitting on my desk … and then back to the draft of a story that could be the most important thing that has happened to me career-wise. I have an invitation to submit to Harpers Magazine (and that is the top) a story on the women’s movement. My thesis is that the rapidly increasing numbers of middle-aged, middle-class housewives being attracted to the movement is having a significant effect on the direction of feminist politics. I have been very involved with the setting up of a chapter of National Women’s Political Caucus here, and have also got many insights from the Department of Continuing Education for Women at Foothill College, which is very active in encouraging frustrated housewives to get back into the mainstream of life.

Of course a go-ahead doesn’t mean the story is sold. I think I have learned a lot about this since last year, when I was so crushed that the famous publishing house which wanted to see my novel sent it back again. But still it’s exciting to have it even considered.

Where are they now, all these articles and stories I worked so hard on? Gone. Never published. Not even copies crammed into my old black filing cabinet. I must have thrown them out in a fit of tidiness, or more likely despair. I can’t even find the kind, hand-written rejection letter from the editor of the famous publishing house, which I know I kept for years. All that’s left is the memory of how hopefully we writers begin new projects again and again and again.

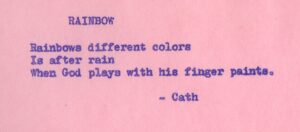

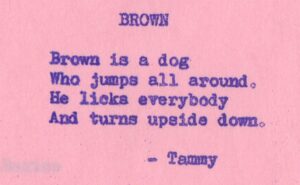

Sharing the joy of language

In my old black filing cabinet I find a treasure: a few stapled sheets of pink copy paper printed with the unmistakable purple ink of a ditto machine. It is the output of my first poetry teaching gig. I explain in a letter to my parents.

In my old black filing cabinet I find a treasure: a few stapled sheets of pink copy paper printed with the unmistakable purple ink of a ditto machine. It is the output of my first poetry teaching gig. I explain in a letter to my parents.

March 1, 1971

I am starting on Friday teaching one hour a week at [my son’s] school. This is what they call a scramble program, where 1st, 2nd and 3rd graders (6-9 yr-olds) are all mixed together to take activities of their own choice, from a list that includes ceramics, folk-dancing, tennis, guitar playing, cookery, woodwork, arts & crafts, etc. The teachers and mothers involved get to teach whatever they are interested in. I am taking a group who are interested in writing poetry. It should be fun, but requires a lot of preparation.

As a university student in New Zealand I had chosen not to make teaching my profession. I’ve not regretted this decision. But over the years I have enjoyed the challenge of teaching short-term writing programs, though even this first one had its moments.

As a university student in New Zealand I had chosen not to make teaching my profession. I’ve not regretted this decision. But over the years I have enjoyed the challenge of teaching short-term writing programs, though even this first one had its moments.

March 29, 1971

My poetry class is coming along quite well, though conditions were a bit poor last week – it was raining, & all the frustrated outdoor games kids crowded into the library too, & my poor kids couldn’t get into the mood.

At the end of the program I would have made enough copies of the pink sheets for all the children in my group to take home. I still remember the frustration of making ditto masters, using a manual typewriter with the ribbon removed. Any mistake and you had to start over. I still remember the smell of the alcohol solvent that permeated the printed pages. I also remember the children’s joy in the power of language.

Today I’d like to give a shout-out to California Poets in the Schools, a program that not only places poet-teachers in classrooms, but also provides training and resources to help them in their work of “empower[ing] students of all ages throughout California to express their creativity, imagination, and intellectual curiosity through writing, performing and publishing their own poetry.” And I’m in awe of the technologies that support a quality of publication way beyond my pathetic purple dittoes.

Saga of an unpublished novel

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a beat-up cardboard box that contains the dog-eared manuscript of my first completed novel in the US, “A Stone from the Wall.” The saga of my attempts to get it published, as reflected in letters to my parents, may get a nod of recognition from other aspiring writers.

March 15, 1972

I have finally got my book off my hands. I received an invitation last week to submit it to Houghton Mifflin Co., one of the most prestigious of the major publishing companies, so after a final frantic effort to finish typing the fair copy, it is now on its way. Whether they will buy it or not is of course another matter, but just to get an editor there enthusiastic about the idea is a tremendous boost. It is their sort of book—a serious look at a contemporary theme. My subject is racial prejudice, and the point I am trying to make is that, for a white person trying to come to terms with racial problems, the most difficult, and even painful, part is learning to recognize your own prejudices. This is mainly, of course, because the more concerned you become, the more you want to think of yourself as one of the good guys.

July 2, 1972

I was going to leave finishing this until after the mailman came today, but don’t really see the point. If I seem a bit edgy in this letter, I am. I was told by Random House that I would hear from them within 4-6 weeks. It is now nearly 5 weeks, and my heart starts hurting every time the mail truck goes up the road. It’s very tedious bracing yourself for rejection every day.

At some point I received a hand-written rejection note from the editor-in-chief of an eminent house—I believe it was Robert Gottlieb of Alfred A. Knopf—who complimented me on my “ability to make my characters come alive,” which buoyed me up for a few more rounds of submission and rejection. I no longer have the note or, for that matter, any of the many rejection notices I received.

July 25, 1972

My book showed up on the doorstep again, as expected. Disappointing of course, but this time I have decided to revise a lot of it before sending it out again. When you are writing fiction, you become in a very real sense the characters you are writing about, and sometimes it is difficult to stand back and look at them objectively—like it is difficult to look at yourself. But now I think I can see at least some areas where the characters are not interesting, or even not alive, but just vehicles for ideas. However, I am going to leave it now until fall—it’s just too difficult to work over the summer. The kids are very good, but they are something of a distraction. In the meantime I have various other articles and poems doing the rounds. They come back periodically, of course, but I figure that with enough things going, I’ll get somewhere eventually. I have had a couple of commissions from Tui [my editor at the Christchurch Press] which I have now sent off … I do still get very depressed every so often, but Tony usually manages to pull me out of it if I can’t shake it off myself. I even made a list this week of all the other things I was going to accomplish this summer. Boring jobs like cleaning the oven figure rather prominently …

November 1972

I am trying to get back to my novel, but keep getting sidetracked with new ideas [for stories and articles]. Have just finished grading a big set of students’ short stories for Millicent [the high school teacher for whom I worked]. Tremendous ideas and effort, but my main reaction as I tore each one apart was, my gosh, that’s what’s wrong with my writing too.

Discouraged, and preoccupied with other projects, I eventually gave up and moved on. As I noted in my blog essay “The Other Side of the Freeway,” I understand now why “A Stone from the Wall” never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject. I didn’t understand how much the life experiences, interests, and even musical tastes of my African-American characters might be different from those of my white characters. Though I devoured my subscription to The Writer magazine from cover to cover, the protocols of book publishing still felt like an enormous black hole. The battered manuscript box deservedly stays in the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet.

A Language to Hear Myself

I started writing poetry in the fall of 1968. I know the date because that was the year my elder son started kindergarten and his two-year-old brother still took afternoon naps, so I had one hour to myself for the first time in five years. I chose poetry partly because it was a short form. An hour would be time, I figured, to write a line or two, or polish an image.

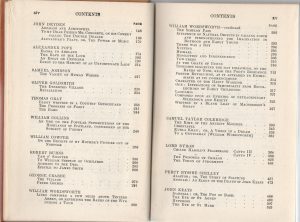

To write well, one needs also to read. I looked around for models. Educated in New Zealand, I had little acquaintance with American poets, and even less with work by women. (The table of contents for my college English I poetry anthology, The English Parnassus (Dixon and Grierson: Oxford 1909), contains no female names.) However, by 1968 I was already becoming acquainted with feminist ideas and literature, such as Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Over the next few years, I sought out female poets.

Anne Sexton’s work immediately caught my attention. Never before had I read poems so uninhibited in their exploration of female sexuality, mental illness, and the constraints of a conventional domestic life. I was particularly excited by Transformations, Sexton’s retelling of well-known tales by the brothers Grimm. Here’s the last stanza of “Cinderella:”

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

Sexton’s retellings bring out the essential unfairness of the old stories’ patriarchal viewpoint. Remember “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” in which an old soldier, having found out the secret of the princesses’ worn dancing shoes, gets to marry his choice of the young women? Here’s Sexton’s wedding scene:

…the princesses averted their eyes

and sagged like old sweatshirts.

Now the runaways would run no more and never

again would their hair be tangled into diamonds,

never again their shoes worn down to a laugh …

Another poet whose books are well represented on my shelves is Denise Levertov. As well as being a beautiful nature poet, she was a passionate protester of the Viet Nam war. This from “The Distance:”

While we are carried to the bus and off to jail to be ‘processed,’

over there the torn-off legs and arms of the living

hang in burnt trees and on broken walls

She also wrote of domestic tasks, such as in this opening stanza of a poem about a visit to her aging mother:

Milk to be boiled

egg to be poached

pot to be scoured.

Many other books by women poets of that era still grace my shelves: Audre Lorde, Sylvia Plath, Marge Piercy, Adrienne Rich, Diane Wakoski, to name a few. A recent exhibition of early feminist poets in the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library collection takes its title from a stanza of the poem “Tear Gas” (1969) by Rich:

I need a language to hear myself with

to see myself in

a language like pigment released on the board

blood-black, sexual green, reds

veined with contradictions

The exhibition’s introductory text by Audre Lorde sums up how I felt as I discovered the feminist poets of the 1960s and ‘70s:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is the vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we give name to the nameless so it can be thought.

The place of art

What is art, and what place has it had in my life? This was the assigned topic for the first set of high school student essays I graded in my first paying job in California. In those days, the late 1960s, California schools had enough money to hire readers to relieve teachers of the time-consuming task of grading papers. I worked primarily with Millicent Rutherford, the Humanities teacher at Lynbrook High School, in the Cupertino Union School District. Over time, we developed a warm friendship.

I was saddened to learn that Millicent died last October, at the age of 91. Her obituary notes: “She will be remembered for her glittering sense of style, her sharp wit, and her boundless energy.” A 1991 Los Angeles Times article on remembering teachers who made a difference includes an anecdote by Stephen Bennett, CEO of AIDS Project Los Angeles:

“We’d study Italian art and [Ms Rutherford] would get . . . photographs from some of the Pompeian paintings that are not typically looked at—the parts of Pompeii they won’t show you because the graphics on the wall are what Americans would consider lewd. And she’d show up in a Pompeian red dress to start the day.”

To honor Millicent’s memory, I’ve been thinking about how I might respond to her essay topic.

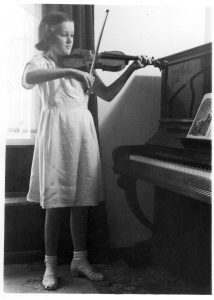

When I was the age of Millicent’s students, music was my passion. I played second violin in my town’s municipal orchestra. At my first concert, the orchestra tackled Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. It must have sounded decidedly amateurish. But the experience of being a part of that magnificent work, of sharing the language of music with my fellow musicians and with an audience, is a thrill that has always stayed with me.

Tauranga Municipal Orchestra at rehearsal in the high school assembly hall, c. 1952. I am in the front row, just to the left of the podium.

Painting too speaks a language without words. On the wall of my office is a reproduction of Georges Rouault’s “The Old King.” I saw the original fifty years ago, at the National Gallery in London. Friends I had come with moved to another room without me as I sat on a gallery bench, weeping. I still weep inside when I look at it.

Concerts, theatre, dance performances and visits to art galleries have always been a major part of my life. The written word has been my personal art form. To struggle with the lines of a poem, to convey emotional meaning through images, leads me to a personal answer to the question: “What is art?” For me, it is a way of sharing what is meaningful in our lives.

When domestic and literary lives collide

Among the battered manuscript boxes in my old black filing cabinet, you won’t find the draft of my first novel. It’s gone, the victim of a long-standing conflict for women between the dream of a writing life and the urge to domesticity.

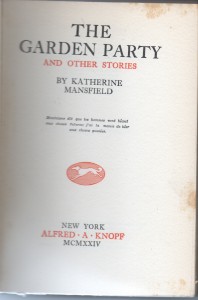

Katherine Mansfield was my heroine and role model. Born in New Zealand in 1888, she too had embarked for England as a young woman determined to make her name as a writer. Through privation and illness she continued to write and publish story collections that made her famous. I could do that too, I told myself.

But there was a variation to our respective histories I had not counted on. In New Zealand before we left, I had given birth to a stillborn daughter. Looking back, I understand that depression fueled by guilt and buried grief over this loss exacerbated the homesickness and culture shock I experienced that first year in England. My unsuccessful search for a writing job did not help. In traditional wifely fashion, I had held off until Tony found work, in a company based west of London, then scrambled, in an unforgivingly tight rental market, to find us somewhere to live nearby. By the time we were settled, a lengthy daily commute into London seemed overwhelming.

I also ran into a catch-22: even though I had been a member in good standing of the New Zealand journalists union, no paper or magazine in London would hire me unless I was a member of the British journalists union, and it was not possible to join that union without first having a job on a paper. When the local newspaper in Windsor turned me down for a posted job because I refused to promise not to get pregnant and ‘waste their time,’ I decided the best thing to do was to start work on my novel and to have another child. I believed, naively, that I could handle taking care of a child and having a writing career. In retrospect, any kind of job would have made better economic sense. We were desperately poor, but the dream of making my way as a writer still held.

I don’t remember much of the plot of that first novel. Two main characters were New Zealand immigrants to England, like ourselves. There was also another couple, and some symmetry of cross-coupling, probably influenced by the Iris Murdoch novels I was reading. I remember feeling uneasy that the plot line was uncovering a sense of dissatisfaction and disillusionment in my own life and that I didn’t know how to resolve the story.

By the time we left England five years later, my world revolved around our two small sons. I found it harder and harder to find time to work on my novel. I pushed aside the dissatisfactions with my own life that the novel echoed. In California things would be different, I told myself. I would devote my life to being a good mother. One bleak winter afternoon as we were packing up to leave the tiny house we had bought in Egham, Surrey, I came to a decision. I was alone, Tony at work, our older son playing at a neighbor’s house, the baby asleep upstairs. Outside under a lowering sky, the baby’s nappies, frozen into boards, hung motionless on the clothesline. Inside, a small coal fire burned in the grate. I sat on the floor in front of the fireplace and fed the unfinished draft of my novel page by page into the flames.

By the time we left England five years later, my world revolved around our two small sons. I found it harder and harder to find time to work on my novel. I pushed aside the dissatisfactions with my own life that the novel echoed. In California things would be different, I told myself. I would devote my life to being a good mother. One bleak winter afternoon as we were packing up to leave the tiny house we had bought in Egham, Surrey, I came to a decision. I was alone, Tony at work, our older son playing at a neighbor’s house, the baby asleep upstairs. Outside under a lowering sky, the baby’s nappies, frozen into boards, hung motionless on the clothesline. Inside, a small coal fire burned in the grate. I sat on the floor in front of the fireplace and fed the unfinished draft of my novel page by page into the flames.

My first cuckoo

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu

Listen to this Medieval rote song

An English oak woodland. Image from Open University on the BBC

My first spring in England, late afternoon in Windsor Great Park. Green-gold light through ancient oaks, the air rich with leaf-mold and violets. A cuckoo calls. I have heard the sound all my life, in music and poems, but never before in the wild.

Listen to the cuckoo calling in this recording from the British Library

As I stand listening, this spring in 1962, something shifts in my thinking. It is as if previously I saw the world through two mesh screens, one named Southern Hemisphere and the other Northern Hemisphere, half a year out of alignment with each other, so that my view was blurred by the moiré patterns their meshes made. The religious festivals my ancestors brought from the northern hemisphere when they emigrated to New Zealand lost their old association with the seasonal cycles of life and death when celebrated in the reversed seasons of the southern hemisphere. In consequence, I felt, even as a child, a subtle sense of having been cut off at the roots, of being, even after several generations, transplanted British.

Images float into my mind. Mid-morning, Christmas Eve, at All Saints Church in Tauranga, NZ. Strewn mounds of flowers deck the chancel steps. The Altar Guild ladies are filling shiny brass vases that stand either side of a red-draped altar. Bronze-purple foliage of copper beech, fans of gladiolus spikes, the tropical exuberance of canna. They add dahlias, roses, bougainvillea until the reds vibrate.

Sunlight through stained glass glitters on the sharp points of holly springs that I strew along the dark wood windowsills, hiding jam jars filled with red geranium flowers. The holly bears no berry here, this time of year, and the carol I hum under my breath echoes in an empty place inside me. Later, at midnight services, the congregation sings of light in darkness and the falling of snow. We emerge to warm air, misty moonlight, and the scent of magnolias. This Christmas is not real, I think to myself. It’s pious make-believe.

Easter: after morning church and family lunch, I gather with siblings and cousins on the porch to smash the Easter eggs we have all been given. Molded of hard sugar, they are pastel pretty, with piped-on decorations of flowers and leaves, the symbols of spring. Having gorged ourselves, we scamper off to scuffle through autumnal leaves.

Cuckoo image from

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

My reading in college, particularly J.G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough, helped me recognize that Christian festivals have pagan roots: the ritual victim dies at planting time; the winter birth is the rebirth of the sun. As the cuckoo calls again, cu-coo, over and over, quietly, the blurred meshes of my hemispheres resolve and I see through: myself and my people bound by tangled apron strings to the life our forbears left, and to the earth itself, an old reality, almost forgotten.

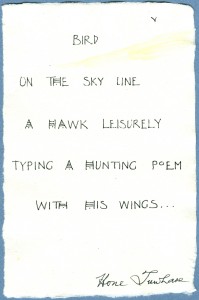

A taonga returns home

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

The manuscript is one my treasured possessions. I have pangs of regret about parting with it, but know I am doing the right thing. In New Zealand Tuwhare’s work is considered a taonga, a treasure. He was the first M?ori poet writing in English to win widespread acclaim. His best-known book, “No Ordinary Sun.” first published in 1964, was reprinted ten times over the next thirty years, becoming one of the most widely read individual collections of poetry in New Zealand history. The title poem is a response to French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Many more collections followed. His work has a conversational tone and incorporates both M?ori and biblical rhythms; the subjects range from the political to the personal and often powerfully evoke the beauties of nature. He won several New Zealand book awards, and was poet laureate of New Zealand in 1999–2000. He died in 2008, at the age of 85.

The M?ori concept of taonga also includes the story that goes along with the item. My little manuscript was a gift from Jean McCormack Tuwhare, Hone’s ex-wife. She and my mother-in-law were friends. On a visit to New Zealand in 2000, I spent a delightful afternoon with Jean at Mother’s house discussing poetry and literature. Mother had shown Jean my first poetry collection, “A Place Called Home,” and later suggested I send her a copy. Enclosed in Jean’s thank-you letter for the book was the Tuwhare manuscript. Unfortunately the letter is lost, but as I recall, Jean wrote that Hone (with whom she was still close friends) liked to practice calligraphy and had given her several of these small pieces to dispose of as she wished. She thought I might appreciate having one.

[Update 6/2/1016: While in New Zealand, I learned from Rob Tuwhare, Hone and Jean’s son, that Jean herself did the calligraphy, and Hone signed her work.]

I am of an age when I need to make decisions about my stuff. Knowing that the manuscript could easily get overlooked among our mountains of paper and art works, I sought professional help. I told Malcolm Moncrief-Spittle of Renaissance Books (New Zealand) , who deals in rare and out-of-print books, that I thought my taonga should be returned to New Zealand. Which university or cultural institution in New Zealand already houses a collection of Tuwhare material and would be a suitable recipient? I asked. He recommended the Hocken Library at the University of Otago in Dunedin.

Staff at the Hocken Library responded to my query with enthusiasm. We’ve arranged a meeting on May 9, when I will hand over the carefully packaged manuscript. I know it will be a happy/sad occasion.

An advocate for junk heaps

Cover and invoice of a 1964 informational booklet, “Creative Play” published by Paul & Marjorie Abbatt, Ltd. Image from Pinterest

By the time I interviewed him in 1963, Paul Abbatt and his wife Marjorie had spent thirty years as advocates for the importance of play in the development of young children and for the betterment of children’s toys and playing facilities. Toys commissioned by their toy company, Paul and Marjorie Abbatt Ltd. of 94 Wimpole Street in London, won prestigious international awards for their good quality and design. Paul Abbatt, whose chief interest was in ‘the ethos behind the business,’ delivered lectures and contributed to academic and professional journals on child development.

In 1963, Abbatt was focusing on outdoor playgrounds for older children. He commented that

“…as a society becomes more urban and industrialised, it becomes more and more hostile to the child and its needs. As buildings are packed closer and closer together, available sites become too valuable for industry, or for car parks, to be used for children’s playgrounds. Even the upper class child with a garden of his own is no better off, for custom demands that his parents keep their grounds neat and spotless, and the child has no opportunity for such fundamental activities as building a den, or digging down to Australia.

In keeping with the stereotypes of his time, by older children he meant older boys, assuming that a girl would be “already a mother with dolls, kitchen, a little house of her own.” The interview continues:

Mr Abbatt believes that the solution to the needs of the older child can be found in the adventure playground. The first of these was built several years ago in Copenhagen, where the designer, instead of putting in the usual concrete shapes, swings and slides, filled his playground with builders’ junk. The playground was a great success, and was copied all over Europe. Some cities produced old cars, or traction engines, used tires, and even an old boat.

The first experimental playgrounds, with their carefully manufactured playing facilities, had not been a success. The children were interested at first, but quickly gravitated to the streets just outside the playground, where they were closer to the real life that they knew. But when the material was provided on the sites for them to build their own dens, they could create their own world inside the playground. “Building a den seems to be fundamental to children’s play, and other activities develop round the original den,” said Mr Abbatt. In Zurich, for example, the gang who inhabited one playground built up such a community spirit that they had their own bank with its own play money, a duplicated magazine, an antique shop, and even a farm with a dozen ducks on a man-made pond. When each gang deserts the playground, as they eventually do, the dens are pulled down, and the next gang to come along starts from scratch with the pile of junk.

In the meantime, in Copenhagen, the first adventure playground has become something of a showplace for visiting social workers. The grounds have been tidied up, and the rough dens turned into pretty villas. The visitors look and admire, but the children no longer come.

Similar problems affect playgrounds in Britain. They are normally noisy, untidy, derelict places, a disgrace to the neighbourhood of neat houses with even neater gardens. So local residents complain, and the council tidies up the playground. “In doing so, they destroy the urge for creative activity that the previous junk-heap gave to the children,” said Mr Abbatt.

In preparation for a conference of the International Council for Children’s Play, which Abbatt helped found, he is making a descriptive survey of children in Britain.

He has invited parents to write and tell him what their children do, and, since small boys particularly are notoriously uncommunicative about the activities of their gangs, he is also seeking information from policemen, schoolteachers, traffic wardens, and others who see the children outside their homes. Already the response from parents has been overwhelming.

He hopes that the survey will provide town planners, architects, and designers, with information on what children really want out of their community.

In a note to my editor, I promised a follow-up when the survey results were in. I’ll talk about that in my next blog piece.