Archive for the ‘writing’ Category

A day at a famous cookery school

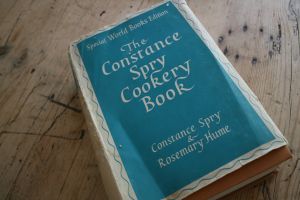

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

As an engagement gift, my future mother-in-law gave me a copy of The Constance Spry Cookery Book. Constance Spry was well known in New Zealand, both for this book and for her several books on flower arranging. When I moved to England in the early 1960s, I was delighted to discover that I lived quite close to Winkfield Place, the school of cookery and domestic arts founded by Mrs Spry and Rosemary Hume, who was also co-director of the Cordon Bleu School in London. A hook for a story for my New Zealand paper was that a NZ girl currently attended the school, so I wangled myself an invitation to spend the day. Here’s what resulted:

A day at a famous cookery school

Even at first sight Winkfield Place is charming. It is a large, white country house, set in broad gardens on the edge of Windsor Forest. Inside, all is bustle and activity. About 100 girls are going about their regular classes: cookery, dressmaking, handwork, flower arranging, shorthand and typing, and another 60 local women are attending demonstrations on cookery and flower arranging. The girls normally spend a year at the school, with a few staying on for a fourth term to take the Cordon Bleu diploma, which is recognised all over the world.

The girls, each in shining white overalls and chefs’ caps, cook in classes of 10. From one kitchen came appetizing smells of spaghetti and baked apples. From another, risotto with a potato salad, and a hazel-nut meringue to be served with an apricot sauce. Miss Hume was found in another kitchen busily stirring whipped cream into a creamed rice pudding. A dish of chopped nuts was waiting to be sprinkled on top.

Later in the afternoon, Miss Hume gave a cooking demonstration. Lotte en mayonaise, tourtiere de boeuf, chicken mousse italienne, and chamonix, were the menu for her supper party. Translated, they were a fish mould gaily decorated with gherkins and chopped parsley, a tasty steak pie, a jellied mould of creamed chicken and shredded ham, and a magnificent dessert of meringue topped with a piped “birds nest” of chestnut puree and whipped cream.

Miss Hume is described by Mrs Spry in her book (which is jokingly referred to as “the bible” at Winkfield) as the authority from whom she obtained all the cooking knowledge she had. She is a tall thin woman, with a strong no-nonsense face, a shy smile, and a deft hand with the pastry. Her guiding characteristics are commonsense and a passion for economy: she believes that all food should be treated with respect, and that to waste it is a crime. She has become expert in parrying the comments of the more snobbish of her day class audiences. One woman, for instance, wondered why she did not use fillet steak in her pie, instead of the less expensive, and less tender, rump steak. Her reply was that fillet was too good for this sort of pie, which was a “cut-and-come-again,” and that the recipe called for a cooking time quite adequate to make the rump tender. Her final comment tactfully vanquished the snob. “I for one would be grateful for a piece of this pie,” she said.

The spirit of Mrs Spry lingers throughout the house. Although few of the present students ever met her, many of the staff, who are old girls of the school, recalled her engaging personality. They spoke of the dinner parties she used to hold on the bare scrubbed table of the diploma group’s kitchen, with the candlelight gleaming on the array of copper utensils on the shelf behind. They described with amusement the clutter of treasures in her flat, and the extraordinary leaps of her conversation. “You will remember, dear,” she would whisper confidentially to one of her students, in the middle of a discussion on current affairs, “that you must always clean out the bath when you get out of it, and hang the bathmat up to dry.” Many remembered her beautiful hands, and her great skill with flowers. With it went the ability to encourage her pupils. Mrs Christine Dickie, now co-principal of the school, described how she herself was never very good with flowers. “But Mrs Spry would come in with a great heap of flowers, and say, ‘Do arrange these for me, dear.’ I would struggle with them, but the result always looked a mess, and I would beg her to show me what to do with them. ‘What’s wrong with that, it looks fine,’ she would say, giving the whole bunch a little tug that made it exactly right. Then I would be rather pleased with myself, although I know deep down that she had done it.”

Mrs Dickie was with Mrs Spry during the founding and early growing pains of the school. “She had that wonderful gift of delegating authority,” she said. “She would forge ahead with some new project, with her ‘dogsbody’ (that was me) beside her, and when the groundwork was laid, she would say, ‘Now you take over – I have other things to do’.” The result was that at her death a few years ago, the staff, although they missed her very much, found that they could continue almost as if nothing had happened. Mrs Spry made provision for this in her will. She instructed that the existing staff were to run the school for three years. If they succeeded in keeping it going, they would be permitted to continue, but if in that time the school went downhill, it was to be closed immediately.

It says much for Mrs Spry’s groundwork, and for the enthusiasm that she had inspired in her staff, that not only has the school survived, but it has had to expand to cope with the increasing demand. There is now a long waiting list for places, and the day classes, about 60 women each on three days of the week, are filled well ahead of each term.

There have been a few changes in the character of the school, and these are ones that reflect an interesting facet of English society, the decline of the debutante. When the school opened, it was regarded as a finishing school for debutantes, as a place to acquire some skill in the domestic arts before coming out into society. To a certain extent this is still true, although of the 100 girls at present at the school, only four or five are potential debutantes, and the social whirl of a debutante’s life is viewed with some scorn by the staff. The others will take up a great variety of careers. Some will go from the secretarial course to office jobs. Many of the girls in the cookery course will go into institutional kitchens, some into private houses. Some will take up other careers, such as nursing. The really dedicated cooks are to be found in the Cordon Bleu diploma class, practically all of whom want to be free lance professional cooks, and spend many of their odd moments discussing the most suitable kit of kitchen equipment to carry with them, or the prospect of gaining experience among their friends.

There are still some girls who will probably not have to earn their living. For them the course provides a convenient stop-gap between school and adult life, in a place where they can learn to grow up pleasantly and happily, while at the same time providing themselves with a form of insurance in case they do have to keep themselves. For them it is also a safeguard against the increasing difficulty of finding domestic staff. Coming from homes where all the housework is done by servants, they realise that for themselves it may be a choice between the cooking and the dusting. The girls who attend Winkfield have plumped for the cooking.

Plumbing crisis brings neighbors together

Windsor Castle in the snow, January 1963. We lived in the town below the castle. Photo by Tony Eppstein.

The winter of 1962-63, my first in England, was the coldest Britain had known in over 200 years. First the fog crept in. My nostrils tightened against the thick yellow damp, sour with the smoke of coal fires and diesel trains. As November wore on and the cold deepened, fog froze into hoar frost that thickened daily on the power lines until they resembled sagging ropes.

Snow began the day after Christmas. All January it snowed and froze and snowed again. Transportation systems ground to a halt. The River Thames froze over. The inside wall of our apartment kitchen, wet since November and already black-mottled with mildew, glazed over with ice. On the outsides of buildings, ice congealed around plumbing outlet pipes like candle wax dripped from lighted candles. Water pipes froze and burst. The clatter of buckets as the water truck made its rounds became a familiar sound in our Windsor neighborhood.

Windsorians walk on the frozen Thames.

A view towards Windsor Bridge photographed on 24 January 1963. Image from the Royal Windsor Website

A side benefit of the bad weather was that we got to know our neighbors. Here’s a letter I wrote to my parents:

23 January 1963

I think we must be drifting into another ice age – the weather here continues to get colder every day. All sources of fuel – coal, gas electricity, and even paraffin, are in short supply, and everyone is fighting a losing battle against frozen pipes and general seizing up.

We had our fun and games over the weekend. We were woken fairly early on Saturday morning to terrific shouting and hammering on the door. We staggered out, to find that the Hoopers were being flooded out – their kitchen was an icy pond, and water was pouring through the light fitting in the ceiling. We turned off all the taps we could find, someone somehow found a plumber, and after he, Tony and Peter [Hooper] had hacked their way through the several inches of ice outside the front gate, and even more ice on top of the valve, they managed to get the mains off. Next thing we tried to get in touch with Stan Fricker, from whose flat the water was coming – he was at work, and we had visions of him coming home to a complete flood. By the time he arrived we had swished most of the water out of the kitchen, and had got all the heaters we could find in to dry it out. So we all trooped up into Stan’s bathroom, which is directly above the Hoopers’ kitchen and, to our surprise, found very little trace of water. We bailed the solid chucks of ice out of the bath, which had been frozen up for days, and Stan and Tony got to work on the floorboards, which were suspiciously damp. They managed to raise a couple, and discovered that the break in the pipe was right underneath the bath, which had been very recently closed in and modernised with plywood, fresh paint, and what not. A brute to get at.

The next thing to do was to find a plumber to fix it – easier said than done – “Oh no, love, we couldn’t possibly let you have one till Monday.” I don’t know how many pennies we spent on phone calls over the weekend, but at fourpence a call we went through several shillings. But we still couldn’t get a plumber till Monday, and late Monday afternoon at that. So we borrowed buckets of water from a neighbor, and puddled along with little dribs of washing where necessary, keeping most of it for drinking. It was pretty messy. At least in the old days they had facilities in keeping with such conditions – but try using a modern-type lav when you have nothing but half a bucket of dirty water to flush it with. That was the first thing that Margaret [Hooper] did, with great ceremony, when the plumber finally managed to get the water on again for us on Monday evening. Our lav had to wait a few hours longer – the remaining water in it had got so iced up that it had to be very carefully thawed before anything would move. And we still can’t have a bath – the outlet pipes in the bathroom are frozen up and, according to the plumber, that will just have to wait till the thaw.

The kitchen outlet, which comes down in the same place – down the outside wall on the coldest side of the house, now shows signs of doing the same thing, which would be choice. I am shortly going to do some washing, and hope that the gallons of hot water from the tub will deter it. Still, we could always throw our slops out the window – if we could unfreeze the windows enough to open them, that is. Might as well be really primitive.

We are getting rather advanced ideas on the proper requirements of a house in this climate – they do not agree very much with the conventional buildings most people live in here. Definitely central heating, double glazing, and interior plumbing.

A Swedish Christmas in London

Last week we went to a Swedish party – the St. Lucia festival, I wrote to my parents from England in mid-December 1962. The background of it seems somewhat confused – the story of a saint mixed up with old pagan mid-winter rites.

My confused reaction to this experience opened me to the concept of cultural adaptation: the way stories and beliefs from one tradition are assimilated into another. Growing up as a Christian in New Zealand, where the seasons are the opposite of the Northern Hemisphere, I was aware of an odd disconnect in the trappings of our festivals, but as yet did not fully comprehend why this should be.

Saffron bread (lussekatter), traditionally served on St. Lucia’s Day. Image from Encyclopedia Britannica.

The event was also a fun field trip for our group of Swedish language students at the College of Further Education in Slough, west of London. Tony and I had become enamored of all things Scandinavian, and hoped to go there one day. Our teacher, Ingrid, the daughter of a diplomat based in London, was eager to introduce us to London’s Swedish community. I tried to summarize her explanation of the festival in my letter, which continues:

The cattle were slaughtered about Dec. 13 for Christmas, and the women used to come out early in the morning with the men’s breakfast. It developed into a ceremony in which a young girl, attended by maidens and young boys, & wearing a head-dress of candles on her head, goes early in the morning to the homes of people in the district bringing hot coffee. Apparently in Stockholm anyway it has developed into a sort of beauty contest, but in London the Swedes are more Swedish than at home & we saw a more genuine procession of children (the little boys looking very self-conscious) singing charming old Swedish carols, & all carrying candles in the darkened room. Very effective & beautiful. The evening finished with coffee & Swedish cakes & pastries at candle-lit tables.

I later learned that before the Christian west adopted the Gregorian calendar in the late 1500s, St. Lucia’s Day fell on the winter solstice, and that it originally honored a goddess who brings the light in the dark Swedish winters. Traces of this solstice celebration linger in the words of the carols sung by the children.

The event we attended at the Swedish church in London also included a crafts fair, which I wrote about for my New Zealand newspaper. Here is the text:

SWEDISH CHRISTMAS DECORATIONS

The straw angel we bought at the church fair. Battered but loved, she still graces the top of our tree.

Our Christmas tree will be decorated with a Swedish angel this year. She is made out of barley straw, pale shining gold pieces neatly tied together. In the early days in Sweden, when the floors of homes were covered with straw to keep out the bitter cold, Christmas guests used to play with the shining straws, plaiting and twisting them into quaint figures. Now Swedish houses are centrally heated, but the custom has persisted, and wherever in the world Swedish people live, at Christmas their homes are always decorated with the golden figures and wreaths.

The Swedish community in London recently held their annual church fair, and out came the traditional Christmas gifts and decorations. As well as the charming angels, there were straw animals, goats and horses and dogs, and handsome plaited wreaths for hanging at the door. Other figures were turned or carved out of wood, and brightly painted. Particularly impressive were ranks of glowing red wooden horses in varying sizes, each painted with gaily decorated harness. Very thin pieces of wood were carved into the tails and wings of formalized birds. By contrast with the tinsel and glitter of English decorations, these traditional designs have a striking simplicity of line and a quaint charm that is refreshing and timeless.

Maureen is exploring an old black filing cabinet that contains 55 years of her papers and memorabilia.

The many names of bread

A cottage loaf. Image from Bewitching Kitchen

Living as I do in Mendocino, CA, I am blessed with access to excellent local bakeries offering a wide variety of breads. I was amused to find in my old black filing cabinet this article I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper about discovering there were more names for bread than “white” and “brown.”

Slindon Bakery’s website has many pictures of these traditional English breads.

A Loaf by Any Other Name

London, 1962

The shelves of a baker’s shop anywhere in New Zealand will be much the same—piled high with round-topped loaves in brown or white, square white sandwich loaves, and pre-cut wrapped bread, and although North Islanders and South Islanders may argue for hours over whether the broken half of the double loaf should be called a “half” or a “quarter”, they will usually be able to make themselves understood in any bakery.

Imagine then the confusion of a New Zealand housewife confronted with the window of an English bakery, filled with loaves in an incredible variety of shapes and sizes. Some of the shapes are wonderfully decorative. There will be long thin loaves and short fat ones, some decorated with grain and some with shining glazes. There will be complicated plaits and squat little knots, enormous swelling crusty loaves, and incredibly long thin rolls that look as if they have been transplanted from the Continent.

The vagaries of English custom have established different names for these traditional shapes from town to town, and sometimes even from shop to shop in the same town.

The biggest and crustiest loaf of them all is usually called a “farmhouse.” It is a tall white loaf, often bursting from a long crack in its top. It has a close relation in the “split tin”, which does not appear to be split at all, but merely a white loaf, again with a cracked top, baked in a narrow oblong tin. These loaves are not to be confused with the “Danish”, which is not baked in a tin at all, but rises as a large oval loaf, dusted with white flour, from a flat tray.

Then there are the more elaborate shapes, such as the “cottage”, often confused with the “farmhouse”. The “cottage” is made with two balls of dough, the smaller being set like a top-knot on top of the larger. Another even more complicated one is the double plait, which contains, as its name implies, two plaits of dough set one on top of the other.

Some of the small round loaves have fascinating names. There is a ball of rich wholemeal bread decorated with wheat grains, which is called, appropriately enough, a “round meal”, but the white ball, this time with a shining brown glaze, is known as a “cob.” This is reputed to be short for “Coburg”, but where this name came from few seem to know.

The origins of other names are more obvious. One delicious scone loaf, which is sold in quarter segments of a large flat disk, is known in England as “Scotch fare”. In Wales, however, they are sold as “Welsh babs”.

A small light white loaf with a shiny glazed crust decorated with diagonal slashes, and known as a “Continental”, has a large elder brother with various titles, but usually known as a “twist” or a “bloomer”. This odd name can cause difficulties, and it has happened that an order for “A large bloomer, thank you” has met with raised eye-brows from the shops that have not heard of this title. In most cases, it is safer to point: “That one over there” and then politely ask the name of the specimen as it is being wrapped up.

Politics in an old English village

My journalist instincts kicked in when I discovered a seething political battle behind a traditional English fair, in Wraysbury, a village on the Thames west of London. In my old black filing cabinet I found a copy of the article I wrote in 1962 for my Christchurch, New Zealand newspaper. I’ve appended a transcript.

A 2014 soccer game on Wraysbury Green. Photo courtesy of Cookham Dean Football Club.

A postscript: the Wraysbury Village Association won their appeal in July 1962. A search on Google Maps shows there is still a substantial green, with playing fields and tennis courts.

LEGAL BATTLE OVER VILLAGE FAIR

In the shade of ancient oaks and chestnuts, where the sweet scent of hay rises from the scythed grass, the sounds of the fair blare out from merry-go-rounds and coconut shies. Across the green, starry with clumps of white daisies, tents and stalls are filled with people inspecting plants, basketwork, and local works of art, or watching a potter at his wheel, or quaffing ale in the refreshment tent.

Wrestlers, fencers and gymnasts display their skills, and a model train, ponies and donkeys give rides across the green to excited children. The soft fluff of dandelion seeds fills the air, and above the trees dozens of swirling balloons make patterns against the warm summer sky. Pretty girls in long skirts, frilly white blouses and straw bonnets are selling programmes.

This is an English country fair, but one with a difference. It is an act of defiance by a village threatened with destruction, a self-consciously archaic revival of an ancient right and custom against the encroachments of suburban London. Its background is a feud that has split the village in two.

Wraysbury, Bucks., was a flourishing village when the Domesday Book was written, and inside its parish boundaries, on an island in the Thames, Magna Carta was signed by King John. Now overhead the whine of airliners rising from London’s Heathrow airport vie for attention with the swooping and twittering swallows. All round the village the tentacles of London’s urban sprawl show themselves in rows of smart modern houses. Closer and closer to the village the heavy machinery of the gravel merchants turns this swampy land on the north banks of the Thames into untidy pools and mounds of gravel.

Now the old manor farm, a relic of feudal times, is to go under the hammer. Most of the farm will be broken up—“for building development and gravel extraction.”

Most of this change has been taken philosophically by the residents of Wraysbury, many of whom have themselves come to the village from the crowded heart of London. But three years ago a crisis developed. A building speculator who had bought part of what was once the village green asked the villagers to waive their rights to this patch of land.

“What rights?” the villagers asked. They discovered that when the great enclosures had taken place in the 18th and early 19th centuries, a private Act of Parliament had in 1803 safeguarded to the use of the villagers certain footpaths down to and along the banks of the Colne Brook, which runs through the village, and also the right to hold, on the Friday afternoon after Whit-Sunday, the ancient and traditional fair on the village green.

This green is now in three sections, one of which was bought by public subscription for the village. Another section was bought by the local tennis club, and the third by the building speculator.

The speculator’s plot, like his request, is insignificant in itself, but the villagers believe that a major principle is at stake, particularly as a gravel contractor at the same time asked for a waiving of rights on one of the old footpaths, in order to extend his gravel extracting operations.

The villagers’ main concern is their remaining village green. If they were to give way in the two present cases, they feel that the Act which safeguards their rights will be undermined, and they will have no means of defending what is left.

When the matter was first broached, friends of the builder called a public meeting of the residents, who turned down the request by about 300 votes to 10. The builder decided, however, to continue his scheme. His opponents formed a residents’ association to protect their rights, accused the parish council of complicity, stupidity, or both, and applied to the court for an injunction to restrain the builder.

On the other side were ranged the parish council, half of whom were replaced by the association’s nominees at the next election, and those builders who were interested in property development, and who considered that the opposition were obstructing legitimate progress.

The association won their case, but an appeal is pending. Meanwhile, they determined to revive the traditional fair, which had not been held for 50 years. The fair itself, like most English country fairs, is a relic of pagan times, when it was a feast to honour gods and heroes. With the coming of Christianity the custom was adapted to a wake, or all-night vigil, which the parishioners spent in the church. It was followed the next day by eating and drinking and rural games.

The wakes, which had by that time become very riotous affairs, were stopped by Henry VIII. Charles I revived the old custom, but took the precaution of ordering that his Justices of the Peace should be responsible for preventing any disorders. By this time the religious aspect of the feast had become of secondary importance, and hawkers and peddlers of merchandise of all descriptions began to put in an appearance.

But the right to hold a fair was still held so sacred that, even through the great enclosures of the agrarian revolution, it was preserved to the village on the remnants of common land. It is this right which the villagers of Wraysbury are defending today. They do not see their fair as a sacred feast, but rather as a symbol of their right to keep a beautiful patch of ground for their, and their children’s recreation.

The explain it in their programme, which describes the purpose of the fair:

“In these days of giant squid corporations and almost omnipotent local authorities, it is by no means impossible that what the Act of 1803 salvaged from the ruins of the old manorial system might yet get mislaid and turn up in somebody’s back yard.”

A single knitting needle

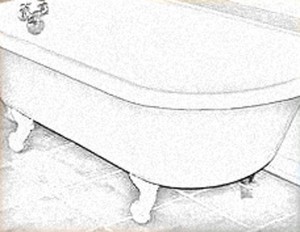

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The flat was part of a semi-detached house dating from the 1870s. The bathroom could have been original. The floor was covered in black and white checkered linoleum, worn white in front of the chipped hand basin. Above the claw-foot tub was a rusty gas-fired contraption that roared to life when you turned on the faucet. The toilet was down the hall, in a more recent addition to the building.

That knitting needle haunted me, as gradually I came to realize it was probably the instrument of an attempted abortion. I longed to know the story of the woman who had pushed it through the crack between the tub rim and the wall. Did she survive?

The conservative New Zealand society in which I grew up had such deep silences around anything to do with sexuality that I was nineteen before I even encountered the word “abortion.” It was in a letter from my mother. “Look it up,” she wrote, her stock response to any question having to do with the body. Mum’s news was that a girl I knew in high school was dead: a move to the city, an affair with a married man, a botched back street abortion, septicemia, the police phoning her parents, saying contemptuously Come and get your kid.

I too have known the desperation of an unwanted pregnancy. I went into marriage in 1960 with what today would seem unbelievable ignorance about sex. The kind ladies at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Christchurch fitted me with a diaphragm and instructed me in how to use it. But the contraceptive methods of those days had a high failure rate. Within a month of the wedding I was pregnant. My new husband was furious with me for stymying his plans to go abroad and make his name in science. I was terrified of the alien life form taking over my body. I tried to recall from novels I’d read how female characters sought to make missed periods come. Scalding hot baths—I tried that. Long, long walks—tried that too, into the seedier parts of the city. If I were to find an abortionist, it would be here. But I had no idea how to find one, and no-one to ask. Besides, I didn’t want to die, like my high school friend.

In time my resistance eased. I was, after all, a respectably married woman. I began to look forward to having a baby. My husband and I postponed the date for our departure to England, and informed the shipping company that we would be traveling with an infant. When our daughter was stillborn, I was devastated, both by the loss, and by the thought that I was being punished for not wanting her in the first place. I buried my grief and guilt deep inside and got on with my life. It took me twenty-five years before I could speak about what had happened, and finally begin to mourn.

In California in the early 1970s I made the acquaintance of a lawyer who had filed an amicus curiae brief in Roe vs. Wade. Together we celebrated that important Supreme Court decision, which affirmed a woman’s right to control her own body. Today I am dismayed that so many people seem to have forgotten, or maybe never knew, what the options were for women when abortion was illegal. The decision to end a pregnancy is never easy. But I, for one, don’t want to go back to the days of the knitting needle hidden under the bathtub.

All a poet can do is warn

All a poet can do today is warn.

–Wilfred Owen

Cream plastic transistor radio close to my ear, I sat by the window of our London bedsitter, hearing familiar words set to brand new music: the premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem”. The May 30, 1962 performance was part of a festival to mark the consecration of St Michaels Cathedral in Coventry, a new modern building set alongside the bombed-out ruins of the old.

I had a personal interest in the cathedral, since one of my assignments for my New Zealand newspaper had been to interview the glass engraver John Hutton, one of the many eminent artists whose work graced the new building.

I was also caught up in the prevailing excitement about the completion of this significant architectural and spiritual project. Contained within the walls of the new cathedral was the idea of reconciliation, that it would be a place that would, in the words of the cathedral website, play a part in

Healing the Wounds of History

Learning to Live with Difference and to Celebrate Diversity

Building a Culture of Peace

But mostly my interest was in the poetry of this new musical work. I had been introduced to the poems of Wilfred Owen in high school. A soldier who died on the battlefield in the last week of the first World War, he wrote searing indictments of that war’s ravages. To me as a student, it was a revelation that poetry could be used to express such pain and anger.

I already had some familiarity with Britten’s music, but I was blown away by the “War Requiem”, which interweaves Owen’s poems with the traditional Latin of the requiem mass. I was brought to tears by Britten’s handling of Owen’s poem of reconciliation, “Strange Meeting,” in the concluding section of the work. In the poem, Owen imagines two dead soldiers, one English, one German, who meet each other

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined

They share life stories:

Whatever hope is yours,

Was my life also; I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world

…

I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled

…

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

The poem ends with the line Let us sleep now … which Britten repeats and extends in a hypnotically murmuring lullaby.

I have listen to the “War Requiem” many times since that memorable evening in London. It still brings me to tears.

A 1963 audio CD of the War Requiem, featuring the soloists for whom it was written, Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Galina Vishnevskaya, is available on Amazon.

A 1963 audio CD of the War Requiem, featuring the soloists for whom it was written, Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Galina Vishnevskaya, is available on Amazon.

The Poetry Foundation website has a good selection of Wilfred Owen’s poems.

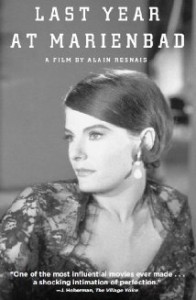

Movies for the intellectual set

“I’ve seen Last Year at Marienbad seventeen times already,” our college friend Bill told us as he showed us around London on our arrival in 1962. “I still haven’t figured out what really happened. I’ll have to go again this weekend.” This enigmatic movie, directed by Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet, is considered a masterpiece of the French New Wave. The movie website rottentomatoes.com comments: “Elegantly enigmatic and dreamlike, this work of essential cinema features exquisite cinematography and an exploration of narrative still revisited by filmmakers today.”

For my husband Tony and me, it exemplified the rich cultural life we discovered in London. In New Zealand, where we grew up, to be an intellectual was to live as a small coterie on the outskirts of society, viewed with suspicion by the mainstream. To be an intellectual in London was to be part of a big vibrant conversation, fueled by articulate reviews of movies, books, art exhibitions, plays and dance performances in the Sunday Times and other papers. In between job hunting and flat hunting, we took the opportunity to participate as much as possible.

Reading again a letter to parents dated April 18, 1962, not long after we arrived, I note a distancing of myself from this new world of ideas, possibly a Kiwi reluctance to admit my eagerness to be part of it. I wrote:

London is chockfull of fascinating characters – you meet them everywhere – on the street, in the Underground. All sorts and shapes and sizes. We met the intellectual set last night – went up to a cinema at Hampstead Village – on the edge of the Heath – which is obviously run by and for the intellectual crowd – hard red and black in the décor, and the finishing touch a handsome beaten copper plaque for the exit sign. They have been showing a series of all Ingmar Bergman, the modern Swedish director’s films. The place was packed out with long hair and beards and intense faces. Almost as interesting to watch as the film. It was a very delicate and charming piece called “Smiles of a Summer Night.” We also saw another interesting film the other night – Alain Resnais’s “Last Year at Marienbad” – highly psychological (and apparently the intellectuals’ current talking-point!) The story (if you can call it that) is that a woman meets a man at a spa who tries to convince her that they were intimate there the previous year, but she thinks she has never seen him before. Scope for highly intriguing playing around with time and facts, with emotional distortions.

London is chockfull of fascinating characters – you meet them everywhere – on the street, in the Underground. All sorts and shapes and sizes. We met the intellectual set last night – went up to a cinema at Hampstead Village – on the edge of the Heath – which is obviously run by and for the intellectual crowd – hard red and black in the décor, and the finishing touch a handsome beaten copper plaque for the exit sign. They have been showing a series of all Ingmar Bergman, the modern Swedish director’s films. The place was packed out with long hair and beards and intense faces. Almost as interesting to watch as the film. It was a very delicate and charming piece called “Smiles of a Summer Night.” We also saw another interesting film the other night – Alain Resnais’s “Last Year at Marienbad” – highly psychological (and apparently the intellectuals’ current talking-point!) The story (if you can call it that) is that a woman meets a man at a spa who tries to convince her that they were intimate there the previous year, but she thinks she has never seen him before. Scope for highly intriguing playing around with time and facts, with emotional distortions.

Over the next few years, we saw almost all of Ingmar Bergman’s movies, which I still love, along with many by the French New Wave directors. I learned to accept that I too was an intellectual.

Over the next few years, we saw almost all of Ingmar Bergman’s movies, which I still love, along with many by the French New Wave directors. I learned to accept that I too was an intellectual.

Droplets in an immigrant wave

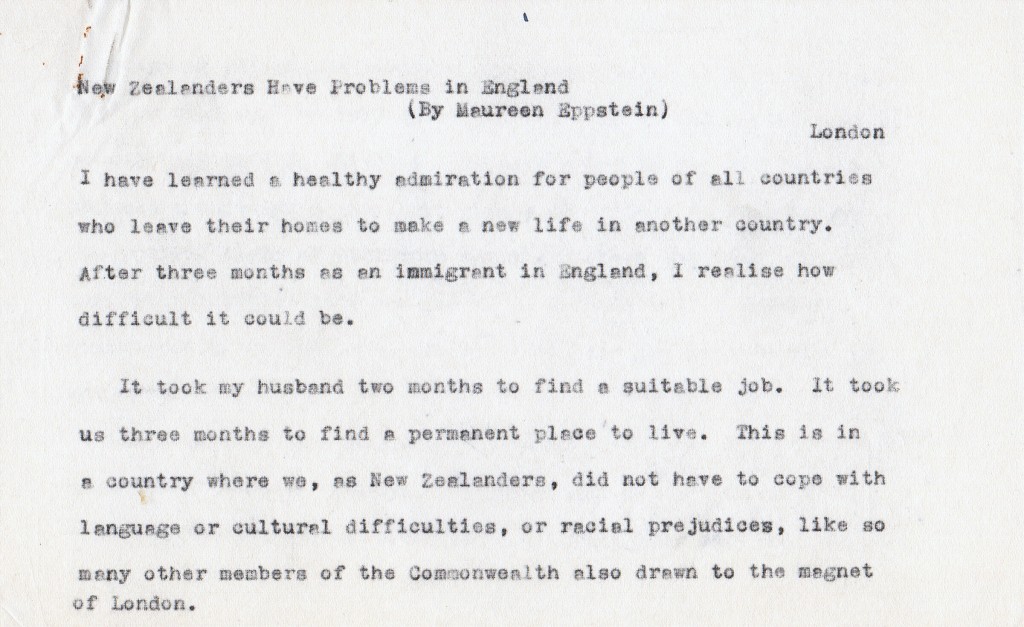

In a 1962 article I wrote for my old paper, the Christchurch (NZ) Press, a draft of which I found in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

I have learned a healthy admiration for people of all countries who leave their homes to make a new life in another country. After three months as an immigrant in England, I realize how difficult it could be.

It took my husband two months to find a suitable job. It took us three months to find a permanent place to live. This is in a country where we, as New Zealanders, did not have to cope with language or cultural difficulties, or racial prejudice, like so many other members of the Commonwealth also drawn to the magnet of London.

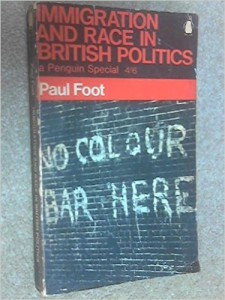

We had no idea at the time of the hugeness of the immigration wave in which we floundered. To aid in post-war reconstruction in the 1950s, Britain had recruited labor from its colonies, primarily the West Indies and the Indian sub-continent. At that time people from the Empire and Commonwealth had unhindered rights to enter Britain. However, by the late 1950s, with the British economy faltering, racial prejudice reared its violent head. The Conservative Party government proposed legislation to make immigration for non-white people harder. One aspect of the proposed bill was to deny entry to dependents of immigrant workers. Before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 could go into effect, the entry of dependents into Britain increased almost threefold as families attempted to beat the deadline. Total immigration from what was known as the New Commonwealth swelled from 21,550 in 1959 to 58,300 in 1960 and a record 125,000 in 1961.

Statistics are from Paul Foot, Immigration and Race in British Politics (Penguin, 1965)

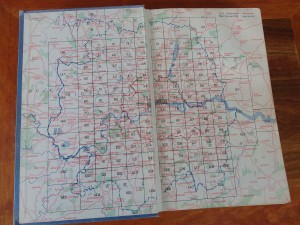

All these people needed somewhere to live. It is no wonder then that rents soared and accommodations of any sort were snapped up. While Tony job-hunted, I haunted rental agencies for a short-term apartment (or flat, as they’re called in England) and, the hefty Bartholomews Atlas of Greater London under my arm, braved the Underground and navigated the suburbs. My letters to parents are full of observations like this one:

It’s amazing how so many of the little villages that have been absorbed into the city still retain their village atmosphere – you pop up from an Underground station and could imagine yourself miles out in the country – unless you happen to be on a bit of a rise, when you see nothing but houses as far as the eye can see. One place I visited, for instance, Muswell Hill, you had to go by bus through a very extensive patch of woodland to get to it. That place I didn’t take, incidentally, because the bath was in the kitchen – covered by a lift-up board and a little frilly curtain. When I mentioned this to another English landlady she didn’t even raise an eyebrow.

My letter continues:

We have now moved out of our hotel into a bedsitter out at Hampstead, for which we are being grossly overcharged – I guess we just took it in a moment of desperation.

The rent was six and a half guineas a week (the same buying power as about $200 in current U.S. dollars.) Every piece of furniture was shaky about the legs, and the cooking facilities were two gas rings crammed into a cupboard with about six inches of counter surface. The shared bathroom was down the shabby hall. I described the landlady as

a bit of a social type – she was too busy preparing for her cocktail party last night to attend to our wants, which brassed me off considerably. Still we get on quite well with her little dog, so with a little careful handling relations might improve.

Relations did not improve. Still vivid in my mind is one of our shouting matches. I had returned from the local laundrette with clothes still damp, in spite of multiple coin feeds to the drier, and had strung clothesline around the room. In walked Mrs. Ashley-Davis. “My furniture! My furniture!” she wailed, hand to her heart. Other disputes must have followed. In a letter to parents dated May 25, after giving the news that Tony had accepted a job near Windsor, I mention that we have given notice

…after some somewhat violent disputes with the landlady, in which I managed to lose my temper – catastrophe!

Finding permanent housing proved even more frustrating. I told my parents:

…for the last three or four days we have been footslogging, railriding, bussing, and generally getting fed up in a wide arc around the area…

We moved out to a hotel near Tony’s new job. My letters for the next few weeks are full of the false hopes and discouragements of the search. Finally we got lucky: a second floor flat in a Victorian brick semi-detached house just down the hill from Windsor Castle. A roof over our heads at last!

Here’s a modern Google Maps street view of the neighborhood. It still looks much the same.

Red is the color of lost empire

In the 1940s, when I was a schoolchild in New Zealand, we used our red pencils to color in maps of the world. Great Britain, of course: England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (Eire was gone by then). Huge chunks of the African continent that still had their old names and boundaries: Sudan, Gold Coast, Cameroons, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Rhodesia, South Africa are just some I remember. The Indian subcontinent with neighboring Ceylon and Burma. Pieces of the East Indies archipelago. Australia, our nearest neighbor. Little red dots, lots of them, for Pacific island dependencies. The big swathe of Canada. More dots in the Caribbean, and a dab for British Guiana on the South American mainland. We pressed our red pencils hardest for New Zealand, the furthest outpost of the British Empire, on which, it was said, the sun never set.

This website has a fascinating time lapse view of

the rise and fall of the British Empire.

Even as we children beamed with pride at our splendid red maps, our world was changing. By the time I moved to England in 1962, the political geography I knew as a child was obsolete. The British had retreated from the Indian Empire, leaving behind a land painfully divided between Hindu and Moslem. The red chunks of Africa rearranged themselves into separate nations. South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand declared themselves a Commonwealth, still recognizing the Queen, but independent of British rule.

Old loyalties die hard. The Union Jack still fills the top left corner of the New Zealand flag. In 1962, New Zealanders still looked to England as the “mother country” and I could write to my parents, in my first letter from London: “[W]e have finally arrived in the Heart of the Empire.”

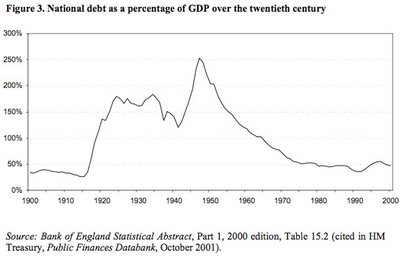

The mood I encountered in the old empire’s capital was bleak. Great Britain had survived World War II, but at an enormous financial cost, and the national debt hung like a shadow over the economy.

After the austerity of the 1950s, living standards were improving, but the country’s wealth, prestige and authority had been severely reduced. Economically, Britain was slipping behind its competitors. Relations between management and labor were bad; the newspapers were full of reports of strikes and unrest. It did not feel like a good place to be starting a new adventure.