Archive for the ‘Mendocino’ Category

How we came to live in Mendocino

We’d never been camping before as a family when, in the summer of 1971, Tony and I decided to take our children, then eight and five, on a short trip to explore some of the northern part of California. On our return, I wrote an ecstatic letter to my parents:

The beach at Russian Gulch State Park, looking under the bridge to the sea. Image by David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons.

25 August 1971

I guess I haven’t told you about our camping trip. We had a marvellous time, and are really sold on camping. We hired a 9×9 tent, and bought a pup tent for the boys, a propane stove and lantern, and a very nice ice box, so we were pretty well set up, and the state park campgrounds are really very civilised, with your own picnic table and food cupboard, and running water, bathrooms and showers not too far way. We spent five nights at Russian Gulch, which is on the Mendocino coast, about 200 miles north of here. This really is a delightful spot. The sea coast here is very rugged, with steep cliffs and caves and tumbled rocks, and grassy meadows on the headlands, with pine and redwood forests behind. The gulch is made by a lush little creek that flows into a tiny cove, making a perfect beach for the children, and the campsites are straggled along the edge of the creek, sheltered from the sea wind, and with a view of redwoods high above you. The weather was beautiful – only a trace of fog a few mornings, and it can be thick all the time. The children got very used to going for long walks, and we also spent a lot of time just sitting and unwinding and watching the wildlife – lots of jays, rabbits, chipmunks and garter snakes. The anchovies were running in the cove, so thick they were being hauled in by waders with nets, and of course they attracted the bigger fish. We were sitting on the beach one afternoon when a group of scuba divers came along with a huge catch, and offered us some, so we had fresh cod for supper.

After describing our impressions of Mendocino village – “splendid weather-beaten old buildings, many of them fine examples of carpenter Gothic, very similar to New Zealand colonial period architecture” – the letter continues:

From Russian Gulch we went on up the coast highway then inland to the Humboldt Redwoods. These are very lovely and impressive, but I think our hearts were still at Russian Gulch.

Here’s where the story takes a mythic turn. Here’s how I tell it now:

Once upon a summer afternoon a man and a woman sat on a beach. As the couple sat and gazed, a young man emerged from the sea. He was beautiful, with golden hair that hung to his shoulders and a body that had known good exercise. From each of his hands hung a fish, whose scales shone wet and silvery.

The woman called out, “Nice catch!” to the fisherman as he passed.

He paused. “Would you like one?”

The woman’s fingers flew to her blushing face. “Oh no, no, I didn’t mean …”

The fisherman lingered. “Please. I have more than I need.” He held out one of the fish.

The man sitting with the woman rose slowly to his feet. The fisherman placed the fish in his out-stretched hands. The man bowed his head and murmured his thanks. That evening, the man and the woman cooked the fish over their campfire and ate its sweet flesh.

After the man and woman returned to the city, every now and then they would feel a tug, as if they were being played on an invisible line. They would say to each other, “We need to go back to that place.” So they would rent a house on the coast for a week or two. The sea sang to them, and each evening a golden light would seep like an enchantment across the drowsy headlands. When their time was up, they would return sadly to the city.

In this way thirty years passed. Each year the tugs grew stronger, the city more and more unbearable. At last they could resist no longer. They left the city. In a house close to where they had eaten the fish, where the scent of the sea came to them, they quietly lived out their days.

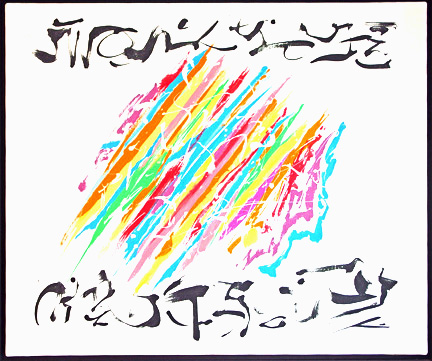

Word Art

I spent this morning thinking about the intersection of writing and art — how we can be moved by a piece of art that involves words, even when the writing is undecipherable. Or when you are ignorant of the language, as I was recently in Istanbul, where I was captivated by the Arabic script that decorated walls of mosques and palaces.

Last night was the opening celebration in Mendocino for the show “Boundless: Art of Letter, Word and Book,” which curator Janet Self describes as a “hands-on conversation about art, language, books, and engagement in the modern age.” I have several pieces in the show: a poem collaged onto a cast paper fish, the poetry box from my vegetable garden, a handmade book that employs a complex flower-fold structure (suggested by Alisa Golden in “Making Handmade Books”), plus some broadsides and tiny chapbooks.

As I looked around the room, I saw uses of the written word that sparkled with creativity. Janet has posted some pictures on her Flockworks blog site. Among my favorites were “House of Cards,” a walk-in house shape whose walls were linked postcards from all over the world, sent years ago to members of the same family, and inherited by the house-maker. I chatted with Harry Van Ornum, a calligraphy student who, having filled his practice paper with lyrics by a favorite singer, turned the paper sideways and continued, making of the words an abstract form. Janet Self, faced with a huge collection of her father’s Reader’s Digest Condensed Books that no thrift store would take, repurposed the pages into large, flowing geometric sculptures.

My favorite encounter was with a young man who stood entranced in front of a calligraphic painting by the late Jim Bertram, one of the artists who helped found the Mendocino Art Center in the 1960s. It was part of a collection being sold as a fund-raiser for Flockworks, the tiny nonprofit that creates such community art projects as the “Boundless” show.

“Excuse me,” he said. “Can you tell me if that calligraphy is in some language?”

Having met and written about Jim Bertram not long before he died, I was able to tell the young man that no, the beautiful shapes were not words. I told him about the quote I found while researching this artist: Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.

“Now I really want that painting,” the young man responded. “I don’t have any money. But next payday, I’m coming back to buy it.”

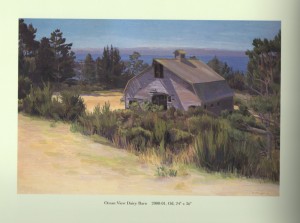

End of an Era for Surfwood Barn

Our local landmark is being demolished. We’ve known it as the Surfwood Barn for the fourteen years we’ve lived here in the Mendocino Coast. It was originally part of the Joy Ranch, and then the Ocean View Dairy, which supplied milk to Mendocino from 1914 to 1939. Since then it has quietly decayed, and has been a favorite subject of plein air painters for decades. This 2001 painting by artist Kevin Milligan is from his book Mendocino: A Painted Pictorial.

The barn now sits on one of the parcels of the Surfwood IV development. We pass it daily on our walks around the neighborhood. We knew that the building, which has been held together for years by aircraft cable, was in a dangerous state, and the current owners of the property had received a demolition permit.

But the arrival of heavy equipment still came as a shock and a sadness.

Citizen/Science

A king tide this morning, and we’d heard that it would be useful for people to document how high the water came, so that we’d have some idea what to expect as climate change brings rises in sea level. An excellent excuse to amble down to Big River Beach in Mendocino with my new camera and practice getting my horizons horizontal.

We’ve had no major rainstorms yet this winter to wash out the sandbar that builds up at the mouth of the river. From a vantage point on the cliff, we watched the tide creep over the bar, then took the old steps down to the beach to check on the tide height at the bridge. Yes, the water was high, too high to walk on sand and touch the bridge pier, as we can usually do.

Strolling back along the tide line, we were enjoying the peace and quiet beauty of the scene when I noticed something that set my teeth on edge: a plastic dog poop bag discarded by a driftwood log. I’ve seen such offerings frequently around this region: beside a signpost, on the edge of a trail. I want to shake the humans who leave them, who are so unclear on the concept of citizenship they have no thought for the environmental mess they are causing. It’s no wonder the sea level is rising.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I plan to read this poem at tonight’s Solstice event at Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino. Obviously it was written in a year other than 2013. We’ve had no rain all month, and none in the extended forecast, so face the likelihood of a drought year. I think of this piece as a kind of prayer.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I honor the rain that plummets from a leaden sky

on this day when the dying sun returns to life.

I honor the wet earth where fungi lift

the smells and secrets of their darkness

into forms potent with wildness

and fallen leaves grow slimy with decay.

I honor the sudden green suffusing

the face of the sun-scorched hill,

like the blush of knowledge in a woman’s face

after her first coupling.

I honor the flame of candle and hearth

that draws to itself the breaths

of all whose lives have sometime crossed,

mingles and transmutes them into warmth

and sends them out into the rain

where they caress the tender growing tips of trees.

Texts

Searoad, a story collection by Ursula K. LeGuin, has a permanent place on my bedside table. It’s there because every now and then I need to reread a certain story. A very short story, less than three pages, it is titled “Texts,” and tells of an older woman who, bombarded by messages and calls to action, retreats to the coastal Oregon village of Klatsand for a month-long winter break. As she walks on the deserted beach, she notices that the waves have left messages in the lines of foam, messages she can almost decipher. The laciness of the foam leads her to speculate that crochet work and lace might also be legible. In a handmade lace collar she reads a message that seems directed to her: “my soul must go, my soul must go … sister, sister, light the light.” There the story ends, with the woman not knowing “what she was to do, or how she was to do it.”

I think of this oddly moving little story every time I walk on Ten Mile Beach, as I did last Sunday. The receding waves left undulating lines of bubbles, iridescent in the hazy sunlight, that popped to form patterns of foam. Scattered across the beach were strands of bull kelp, dried into coils and loops that lay like a cursive script on the sand.

Yesterday, when the wind was brisk and the sea streaked with white caps, I remembered an interview I did for the Mendocino Art Center magazine. It was part of a series I wrote on artists who helped found the art center in the 1960s. By the time I met Jim Bertram in the early 2000s, he was senile and nonverbal, so I had to rely on material in the art center archives for information about his background and artistic vision. Nevertheless, Jim and I spent a wonderful afternoon together. I think a poem I wrote at the time sums it up:

MESSAGES

For JB

“Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.”

– Jim Bertram

These bright spring days, when the wind

scribbles its white calligraphy

on a wash of aquamarine,

I think of the artist in his studio

upstairs of a weathered storefront

overlooking Mendocino Bay.

Sheet after curling sheet he showed me, canvas

after canvas, covered with calligraphic forms

that could have been words, but were not.

In our shared silence I understood his drift:

how sometimes what matters most is inarticulate:

like the line of spray from a lifting wave,

the hand of an old man painting messages of love.

On my way downstairs from Jim’s studio, I fell in love with one of his paintings, which now has a place of honor in my house. I smile when I read its message.

Battle of the Rose Roots

I should have learned from experience. Years ago, I wondered why plants near a hedge in my Palo Alto garden weren’t doing so well, in spite of soil amendments, regular watering, and other tender loving care. Investigating closer, I found that below the soil surface was a dense mass of tiny white roots. The nourishment stealer was a Banksia rose that had flourished in the hedge for fifty years.

You would think I’d learn and remember. But no … As we designed a deer-fenced vegetable garden for our new home on the edge of the forest in Mendocino, we decided that a covered gate, an English lych-gate, would be a charming touch. And wouldn’t it be romantic to have a rose climbing over it? I’ve always been fond of “Mrs. Cecille Brunner” with its exquisite miniature pink buds.

I planted a climbing “Mrs. B” in a half wine barrel just inside the gate, out of the deer’s reach. Years passed. At a friend’s house I admired another pink climber. She told me its name, “Seven Sisters,” and offered a cutting. The local legend, she told me, was that this rose was originally brought to the Northern California coast by a Russian princess in the early 1800s. Possibly she was the well-born wife of Ivan Kuskoff, commander of the Russian American Company fur trading post at Fort Ross, whose house is still standing, and is now a National Historic Landmark. According to the story, Madame Kuskoff gave cuttings of “Seven Sisters” to friends, who gave cuttings to friends, and so it moved up the coast. I see it everywhere in the gardens of old coast homes, and have met the woman who gave my friend her cutting.

But I digress. Needless to say, my cutting of “Seven Sisters” also found a home in a wine barrel inside my fenced garden. It became a yearly task to prune these enthusiastic climbers before they totally blocked the sun from the vegetables.

This year “Seven Sisters” decided to bloom again just as I was getting out my pruning shears, so she’s still a wild tangle.

But tidy on top doesn’t mean disciplined underneath. This season I noticed that the vegetables in raised beds near the roses were stunted and sad. One scoop with the shovel showed the cause. Nothing for it but to dig out the entire bed.

There’s a layer of hardware cloth on the bottom to keep out the gophers (that’s another story). I’m hoping a couple of layers of weed cloth will deter the rose roots, at least for a few years. My friend, a Master Gardener, laughed when I told her. “You’re the eternal optimist, aren’t you?” she said.

Wave/Rock

I’m jealous of Scottish visual poet Ian Hamilton Finlay.

Last Sunday morning I walked on the cliffs at Chapman Point, just south of Mendocino. Tony, who does the graphics for Mendocino Coast Writers Conference, was taking photographs that might become next year’s program cover or a display ad in Poets & Writers magazine . I contemplated spume lifting from waves as they rolled in steady rhythm against the rocks, and thought about words I might use to convey the sense of transience that pervades this dramatic boundary between earth and sea.

Back home, I started making a list: undercut, backwash, swirl, surge, strata, submerge, carve, crevice, recede, collapse, uplift, unrest, rockfall, bull kelp, blueness, sheer … A few lines started to appear:

In the curve of the undercut

at the cliff’s base

the shape of wave

I decided to let the lines sit for a while and turned to another project. My friend Mary Marcia Casoly had recently sent a link to an anthology, Shadows of the Future: An Otherstream Anthology containing two of her poems. “Vispo,” she called them, visual poetry. Not a form I knew much about, so I Googled it and found a number of sites that had definitions and examples. Visual poetry, I learned, is “poetry that cannot suffer any translation into alternative visual or typographic form without sacrificing some of its meaning and integrity… The ‘quality of presence’ we get from the work depends on visual means, such as typefaces, format, spatial distribution on the page, or the physical form of the book or book object.” (Johanna Drucker)

I opened an example at random. Immediately my entire afternoon at my desk was washed out to sea. Before me was Ian Hamilton Finlay’s “Wave/Rock” from Aspen #7. Just two words repeated: the brown rockrockrock stacked on top of each other so that the near-vertical strata are visible; the blue wave words spread and broken as they crash against the rocks.

Sweet Peas

The 2012 Mendocino Coast Writers Conference ended last night. This morning I picked sweet peas. Over my four-day absence to run the conference, the stems that had been in bud were in full flourish, and the row of pea plants sprawled even more rampantly over chard and carrots in my vegetable garden. I picked enough to refill vases of crumpled has-beens in my house, enough to give away to a friend, enough to fill yet more vases. I pressed my nose into the bouquet, sweet as the hugs of farewell and murmured words of thanks at the conference’s closing dinner.

The scent restored my faith in myself, both as the director of a successful conference, and as a grower of sweet peas. Back when I was a child in school, growing sweet peas was part of the curriculum, like spelling and arithmetic. Each year the Important Visitor would bring the signup sheet and reveal the wondrous names of new varieties. On Seed Day the visitor would return. Precious pennies would be offered up for hard black miracles. The visitor would give instruction in the mysteries of sweet pea growing. We must dig a trench two feet deep. The layer of compost in the bottom of the trench must be at least six inches before we shoveled back the dug and loosened earth. We must soak the seeds in water overnight, then plant exactly one inch deep, and four apart.

The best on Judgment Day took front row place at the flower show, a ribbon tucked beneath a jam jar that held three specimens, each with four blooms on a long stem. My jar sat humbly at the back. I was racked with guilt for shorted measure on the trench. The ground was hard, and my arms ached. My Dad’s compost pile yielded only a thin layer of partially composted weeds. I had tossed in some fresh grass clippings, but even those did not make up the required six inches. The seeds germinated, but the plants were spindly, and none of their flower stems boasted more than three blooms.

The guilt stayed with me all my life. Not enough my love for their bright beauty, not enough my penitence. I was cast down.

This year I decided to try again. A raised vegetable bed had an empty row next to a sheltered wall covered with a strong wire trellis. Remembering my past efforts, I figured that would be enough space. I dug in a bag of soil conditioner with an impressive ingredients list: composted firbark, chicken manure, earthworm castings, bat guano and kelp meal. I planted my seeds, an old-fashioned mix from Renee’s Garden, careful to places them one inch deep and four apart.

The seeds grew. And grew. I wound string from post to post to hold the plants against the trelllis. More string. A length of chicken wire that bulged and sagged. A couple of tomato frames. Soon I gave up. The chard was running to seed anyway, and the carrots were mature enough to survive the shade.

This morning as I teetered on a step-stool to pick the flowers, the thought came to me that their exuberant growth was akin to the joy conference participants were expressing. The Mendocino Coast Writers Conference has as its mission to offer a place where writers find encouragement, expertise and inspiration. This year it all came together. A brilliant group of faculty shared their expertise with participants dedicated to improving their craft, nurtured by a team of volunteers so cohesive that the flow of events was seamless.

Today we’re all exhausted and resting up. Tomorrow we start planning MCWC 2013.

Prison Guard-ening

On top of the roadbank, I am fastening circles of heavy wire mesh around young Leyland Cypresses. A passing neighbor calls a greeting. “Prison guard-ening?” she asks.

“Yeah,” I reply with a shrug of despair. She too is a gardener. She understands.

Ever since my husband and I built this house at the edge of the forest, we have tried to live in respectful community with the creatures who were here before us. Jackrabbits, foxes and bobcats use our ground-level front porch as a convenient highway. My vegetable garden is fenced off, but the resident blacktailed deer amble through the rest of the garden wherever they please. They even help by pulling juicy weeds from among the deer-resistant perennials and by keeping down the path to the compost bins more efficiently than a lawn-mower.

The only problem I have is with the bucks, who scrape off the velvet covering their antlers by rubbing them against young trees and shrubs. Already some of the cypresses show the telltale signs: a snapped-off branch or frond turning brown, a length of the trunk rubbed raw. It’s a mating signal, I understand, with several facets: the visual sign left by the buck’s rubbing, chemical signals from glands on the buck’s face, and the sound of the buck thrashing branches of the tree on which it is rubbing. I once watched a large buck do battle with a stiff and spiny Ceonothus bush by the driveway. Again and again he attacked, as if determined to demolish it. Here on this roadbank I have lost a Pacific Wax Myrtle and a couple of Shore Pines to such opponents. The Cypresses are a replacement, to help fill in a windbreak against our fierce nor’westers. I can’t afford to lose them too.

The prison cages are unsightly, and don’t fit with the natural landscape I’d like to have. But Cypresses grow quickly; soon their foliage will hide the wire. Sometimes compromises must be made.