Archive for the ‘books’ Category

Looking back at a life

The cover image is a detail from the watercolor painting “Under the Fog” by Mendocino Coast artist Karen Bowers.

So far this blog has been a form of memoir: small stories and reflections about some aspect of my history. Today I break that pattern to tell you about another aspect of my writing life, poetry. I’m excited to announce that my latest collection of poems, Horizon Line, will be published next April by Main Street Rag Publishing Co. The publisher has set up a handsome webpage where you can place pre-publication orders at a substantial discount from the $14 list price.

Horizon Line is also a kind of memoir. The title poem sets the theme of the book: “To limn a life in perspective …” From my house on the Mendocino Coast in Northern California, I watch the sea fog move in and out, changing as it does the viewer’s perception of where the horizon is. I use this variability as a metaphor for what it’s like to look back on my life. Here’s the poem in full:

Horizon Line

To limn a life in perspective

the artist first defines

a horizon line eye level to the viewer.

From my hill of years the horizon

is fluid as in watery, but also

as in unpredictable.

On the sea’s face a wall of fog

moves in and out like histories

remembered and forgotten.

Sometimes silver striates the sea

with such a glitter of insight

I am bedazzled and cannot look.

Sometimes fogbank and ocean

merge with such blue-gray unity

it seems the horizon rises

so that I stand on the shore

dwarfed by a surf of knowledge

that pounds at my ignorance.

Sometimes the sea becomes invisible

the white air a questioning emptiness

a finger-touch of damp against the cheek.

Indigo Moor, Poet Laureate of Sacramento Emeritus, said this about the collection:

In her new poetry collection, Horizon Line, Maureen Eppstein takes an imagistic look at the systole and diastole of the immigrant experience. Divided into four chambers, Horizon Line presents a New Zealand eye’s view of the American experience, from the landing on these shores, through the struggle for spirituality, and, finally, to the unerring clarity of the clearing at the end of the path.

Like a retrospective exhibition of an artist’s work, I see this book as a summing up of my spiritual and artistic journey. I would be honored to have you as one of my readers. Again, here’s the link for ordering Horizon Line:

The way we learn to belong

Once more we are at that seasonal turn familiar in California history: after a winter of great rains, floods and mudslides, the promise of an extraordinary blaze of color as wildflowers burst into bloom. My first experience of this magical transition was in 1969, my second spring in this new country. I describe it in letters to parents:

Feb. 28, 1969

It has actually stopped raining for the past hour. Another shower on the way, of course, but such a respite to see the sun. We have been averaging one sunny day a week for the past two months, and the general situation is already critical. We are not doing too badly in the Santa Clara Valley. All the creeks are contained by reservoirs up in the hills, and although the largest one, Anderson, is spilling over the top and flooding parts of east-side San José, the others are still holding their own. Fortunately the weather-man had predicted a respite for the next four or five days, i.e., drizzle instead of a deluge, and the authorities are hoping to get enough water away through the sluices of the other six dams during this time to make room for next week’s storms. Where we live is on relatively high ground anyway, so it is unlikely that we would be affected. The really big headache though is Central Valley, which drains the whole of the Sierra Nevada range. The Sacramento-San Joachim delta has flooded twice already in the past two months, and the river levels are still dangerously high. But in the high Sierra the snow fall is already twice the annual average, and we are only one third through the rainy season. Sooner or later that stuff is going to thaw, and if there is a warm rain up there, the effect will be sudden and disastrous. Meanwhile, it is still raining, with violent storms rolling in from the Pacific with tedious regularity. For some vast meteorological reason, the storm belt has swung further south than normal this year—so we are getting what Alaska usually gets. (They say it’s a mild winter in Alaska this year!)

A field of mixed wildflowers: Arroyo Lupine, Baby Blue-eyes, Purple Owls Clover and Tidy-tips. Image from Mother Nature’s Backyard.

And a few weeks later:

April 14, 1969

[After a visit to the Lick Observatory on Mt. Hamilton] We decided to see what it was like on the other side of the mountain. We found ourselves in a charming little valley, the San Antonio, which we followed back to Livermore and the freeway home. The land in this part is lightly wooded, and very sparsely populated—we saw a few ranch houses, occasional small herds of cattle, the odd horseman and dog, and that’s all. And at this time of year, the earth between the trees is covered with fresh grass, so scattered and strewn with wildflowers that it looks like some magic carpet.

I think it is one of the most wonderful sights I have ever seen. Great swathes of colour, of every shade. One they call Sunshine, or Goldfields, a tiny daisy-like flower, brilliant yellow. It grows only a few inches high, but in such profusion that, as its name implies, it makes a great field of colour. And on the slopes of Mt. Hamilton we thought for a while the snow was still lying, there were such patches of a snowy white flower. But other colours too, pinks and blues right through to the purples and reds. And down in the lower valleys, the California poppy, a brilliant orange. …I love these flowers so much.

An interviewer recently asked me what moved me toward writing about nature. I replied that as an immigrant, learning about the land was a big part of learning to belong to my adopted country. I’ve found this be particularly true when I moved from the Bay Area to the Mendocino coast. I’ll always be grateful to Dr. Teresa Sholars, whose College of the Redwoods wildflower identification class gave me the names of beloved beauties. Here’s a poem about them:

California Wildflowers

It seems a simple joy

to greet the flowers by name

Tidy Tips, Goldfields, Blue-Eyed Grass,

Crane’s Bill and Cream Cup,

Sticky Monkey Flower,

Mule’s Ears, Owl’s Clover,

Sun Cups glossy by the path,

Milkmaids in shade,

Lupine and Poppy on the slope,

but to the immigrant who after 40 years

still speaks with foreign intonation,

these are pet-names for familiars

precious as friends,

who speak in a language without words

of soils: clay and serpentine,

of rains and drought,

the way the lineaments of the land

impress themselves,

the way we learn to belong.

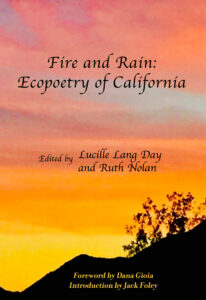

In a couple of days I’m off to Portland, OR for the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) conference. I was invited to be part of a group representing Scarlet Tanager Books, publisher of the anthology Fire & Rain: Ecopoetry of California, in which I have several poems. We’re hosting a reception at the conference, and doing a reading at a neighboring bookstore. Being recognized as an “ecopoet of California” makes me feel that, after what is now 52 years, this beautiful state is home. Enjoy this season’s flowers.

Saga of an unpublished novel

In the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet sits a beat-up cardboard box that contains the dog-eared manuscript of my first completed novel in the US, “A Stone from the Wall.” The saga of my attempts to get it published, as reflected in letters to my parents, may get a nod of recognition from other aspiring writers.

March 15, 1972

I have finally got my book off my hands. I received an invitation last week to submit it to Houghton Mifflin Co., one of the most prestigious of the major publishing companies, so after a final frantic effort to finish typing the fair copy, it is now on its way. Whether they will buy it or not is of course another matter, but just to get an editor there enthusiastic about the idea is a tremendous boost. It is their sort of book—a serious look at a contemporary theme. My subject is racial prejudice, and the point I am trying to make is that, for a white person trying to come to terms with racial problems, the most difficult, and even painful, part is learning to recognize your own prejudices. This is mainly, of course, because the more concerned you become, the more you want to think of yourself as one of the good guys.

July 2, 1972

I was going to leave finishing this until after the mailman came today, but don’t really see the point. If I seem a bit edgy in this letter, I am. I was told by Random House that I would hear from them within 4-6 weeks. It is now nearly 5 weeks, and my heart starts hurting every time the mail truck goes up the road. It’s very tedious bracing yourself for rejection every day.

At some point I received a hand-written rejection note from the editor-in-chief of an eminent house—I believe it was Robert Gottlieb of Alfred A. Knopf—who complimented me on my “ability to make my characters come alive,” which buoyed me up for a few more rounds of submission and rejection. I no longer have the note or, for that matter, any of the many rejection notices I received.

July 25, 1972

My book showed up on the doorstep again, as expected. Disappointing of course, but this time I have decided to revise a lot of it before sending it out again. When you are writing fiction, you become in a very real sense the characters you are writing about, and sometimes it is difficult to stand back and look at them objectively—like it is difficult to look at yourself. But now I think I can see at least some areas where the characters are not interesting, or even not alive, but just vehicles for ideas. However, I am going to leave it now until fall—it’s just too difficult to work over the summer. The kids are very good, but they are something of a distraction. In the meantime I have various other articles and poems doing the rounds. They come back periodically, of course, but I figure that with enough things going, I’ll get somewhere eventually. I have had a couple of commissions from Tui [my editor at the Christchurch Press] which I have now sent off … I do still get very depressed every so often, but Tony usually manages to pull me out of it if I can’t shake it off myself. I even made a list this week of all the other things I was going to accomplish this summer. Boring jobs like cleaning the oven figure rather prominently …

November 1972

I am trying to get back to my novel, but keep getting sidetracked with new ideas [for stories and articles]. Have just finished grading a big set of students’ short stories for Millicent [the high school teacher for whom I worked]. Tremendous ideas and effort, but my main reaction as I tore each one apart was, my gosh, that’s what’s wrong with my writing too.

Discouraged, and preoccupied with other projects, I eventually gave up and moved on. As I noted in my blog essay “The Other Side of the Freeway,” I understand now why “A Stone from the Wall” never found a publisher. I was way too new to this country, and way too naïve, to do justice to its thorny subject. I didn’t understand how much the life experiences, interests, and even musical tastes of my African-American characters might be different from those of my white characters. Though I devoured my subscription to The Writer magazine from cover to cover, the protocols of book publishing still felt like an enormous black hole. The battered manuscript box deservedly stays in the bottom drawer of my old black filing cabinet.

A Language to Hear Myself

I started writing poetry in the fall of 1968. I know the date because that was the year my elder son started kindergarten and his two-year-old brother still took afternoon naps, so I had one hour to myself for the first time in five years. I chose poetry partly because it was a short form. An hour would be time, I figured, to write a line or two, or polish an image.

To write well, one needs also to read. I looked around for models. Educated in New Zealand, I had little acquaintance with American poets, and even less with work by women. (The table of contents for my college English I poetry anthology, The English Parnassus (Dixon and Grierson: Oxford 1909), contains no female names.) However, by 1968 I was already becoming acquainted with feminist ideas and literature, such as Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Over the next few years, I sought out female poets.

Anne Sexton’s work immediately caught my attention. Never before had I read poems so uninhibited in their exploration of female sexuality, mental illness, and the constraints of a conventional domestic life. I was particularly excited by Transformations, Sexton’s retelling of well-known tales by the brothers Grimm. Here’s the last stanza of “Cinderella:”

Cinderella and the prince

lived, they say, happily ever after,

like two dolls in a museum case

never bothered by diapers or dust,

never arguing over the timing of an egg,

never telling the same story twice,

never getting a middle-aged spread,

their darling smiles pasted on for eternity.

Regular Bobbsey Twins.

That story.

Sexton’s retellings bring out the essential unfairness of the old stories’ patriarchal viewpoint. Remember “The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” in which an old soldier, having found out the secret of the princesses’ worn dancing shoes, gets to marry his choice of the young women? Here’s Sexton’s wedding scene:

…the princesses averted their eyes

and sagged like old sweatshirts.

Now the runaways would run no more and never

again would their hair be tangled into diamonds,

never again their shoes worn down to a laugh …

Another poet whose books are well represented on my shelves is Denise Levertov. As well as being a beautiful nature poet, she was a passionate protester of the Viet Nam war. This from “The Distance:”

While we are carried to the bus and off to jail to be ‘processed,’

over there the torn-off legs and arms of the living

hang in burnt trees and on broken walls

She also wrote of domestic tasks, such as in this opening stanza of a poem about a visit to her aging mother:

Milk to be boiled

egg to be poached

pot to be scoured.

Many other books by women poets of that era still grace my shelves: Audre Lorde, Sylvia Plath, Marge Piercy, Adrienne Rich, Diane Wakoski, to name a few. A recent exhibition of early feminist poets in the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library collection takes its title from a stanza of the poem “Tear Gas” (1969) by Rich:

I need a language to hear myself with

to see myself in

a language like pigment released on the board

blood-black, sexual green, reds

veined with contradictions

The exhibition’s introductory text by Audre Lorde sums up how I felt as I discovered the feminist poets of the 1960s and ‘70s:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is the vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we give name to the nameless so it can be thought.

A day at a famous cookery school

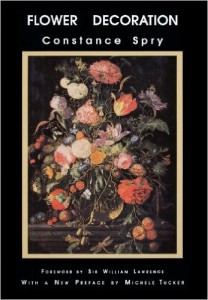

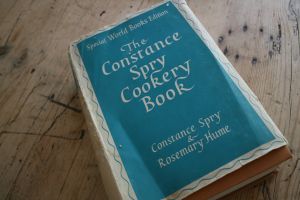

Cookbook cover, considerably more pristine than my beat-up copy. Image from http://magazine.direct2florist.com

As an engagement gift, my future mother-in-law gave me a copy of The Constance Spry Cookery Book. Constance Spry was well known in New Zealand, both for this book and for her several books on flower arranging. When I moved to England in the early 1960s, I was delighted to discover that I lived quite close to Winkfield Place, the school of cookery and domestic arts founded by Mrs Spry and Rosemary Hume, who was also co-director of the Cordon Bleu School in London. A hook for a story for my New Zealand paper was that a NZ girl currently attended the school, so I wangled myself an invitation to spend the day. Here’s what resulted:

A day at a famous cookery school

Even at first sight Winkfield Place is charming. It is a large, white country house, set in broad gardens on the edge of Windsor Forest. Inside, all is bustle and activity. About 100 girls are going about their regular classes: cookery, dressmaking, handwork, flower arranging, shorthand and typing, and another 60 local women are attending demonstrations on cookery and flower arranging. The girls normally spend a year at the school, with a few staying on for a fourth term to take the Cordon Bleu diploma, which is recognised all over the world.

The girls, each in shining white overalls and chefs’ caps, cook in classes of 10. From one kitchen came appetizing smells of spaghetti and baked apples. From another, risotto with a potato salad, and a hazel-nut meringue to be served with an apricot sauce. Miss Hume was found in another kitchen busily stirring whipped cream into a creamed rice pudding. A dish of chopped nuts was waiting to be sprinkled on top.

Later in the afternoon, Miss Hume gave a cooking demonstration. Lotte en mayonaise, tourtiere de boeuf, chicken mousse italienne, and chamonix, were the menu for her supper party. Translated, they were a fish mould gaily decorated with gherkins and chopped parsley, a tasty steak pie, a jellied mould of creamed chicken and shredded ham, and a magnificent dessert of meringue topped with a piped “birds nest” of chestnut puree and whipped cream.

Miss Hume is described by Mrs Spry in her book (which is jokingly referred to as “the bible” at Winkfield) as the authority from whom she obtained all the cooking knowledge she had. She is a tall thin woman, with a strong no-nonsense face, a shy smile, and a deft hand with the pastry. Her guiding characteristics are commonsense and a passion for economy: she believes that all food should be treated with respect, and that to waste it is a crime. She has become expert in parrying the comments of the more snobbish of her day class audiences. One woman, for instance, wondered why she did not use fillet steak in her pie, instead of the less expensive, and less tender, rump steak. Her reply was that fillet was too good for this sort of pie, which was a “cut-and-come-again,” and that the recipe called for a cooking time quite adequate to make the rump tender. Her final comment tactfully vanquished the snob. “I for one would be grateful for a piece of this pie,” she said.

The spirit of Mrs Spry lingers throughout the house. Although few of the present students ever met her, many of the staff, who are old girls of the school, recalled her engaging personality. They spoke of the dinner parties she used to hold on the bare scrubbed table of the diploma group’s kitchen, with the candlelight gleaming on the array of copper utensils on the shelf behind. They described with amusement the clutter of treasures in her flat, and the extraordinary leaps of her conversation. “You will remember, dear,” she would whisper confidentially to one of her students, in the middle of a discussion on current affairs, “that you must always clean out the bath when you get out of it, and hang the bathmat up to dry.” Many remembered her beautiful hands, and her great skill with flowers. With it went the ability to encourage her pupils. Mrs Christine Dickie, now co-principal of the school, described how she herself was never very good with flowers. “But Mrs Spry would come in with a great heap of flowers, and say, ‘Do arrange these for me, dear.’ I would struggle with them, but the result always looked a mess, and I would beg her to show me what to do with them. ‘What’s wrong with that, it looks fine,’ she would say, giving the whole bunch a little tug that made it exactly right. Then I would be rather pleased with myself, although I know deep down that she had done it.”

Mrs Dickie was with Mrs Spry during the founding and early growing pains of the school. “She had that wonderful gift of delegating authority,” she said. “She would forge ahead with some new project, with her ‘dogsbody’ (that was me) beside her, and when the groundwork was laid, she would say, ‘Now you take over – I have other things to do’.” The result was that at her death a few years ago, the staff, although they missed her very much, found that they could continue almost as if nothing had happened. Mrs Spry made provision for this in her will. She instructed that the existing staff were to run the school for three years. If they succeeded in keeping it going, they would be permitted to continue, but if in that time the school went downhill, it was to be closed immediately.

It says much for Mrs Spry’s groundwork, and for the enthusiasm that she had inspired in her staff, that not only has the school survived, but it has had to expand to cope with the increasing demand. There is now a long waiting list for places, and the day classes, about 60 women each on three days of the week, are filled well ahead of each term.

There have been a few changes in the character of the school, and these are ones that reflect an interesting facet of English society, the decline of the debutante. When the school opened, it was regarded as a finishing school for debutantes, as a place to acquire some skill in the domestic arts before coming out into society. To a certain extent this is still true, although of the 100 girls at present at the school, only four or five are potential debutantes, and the social whirl of a debutante’s life is viewed with some scorn by the staff. The others will take up a great variety of careers. Some will go from the secretarial course to office jobs. Many of the girls in the cookery course will go into institutional kitchens, some into private houses. Some will take up other careers, such as nursing. The really dedicated cooks are to be found in the Cordon Bleu diploma class, practically all of whom want to be free lance professional cooks, and spend many of their odd moments discussing the most suitable kit of kitchen equipment to carry with them, or the prospect of gaining experience among their friends.

There are still some girls who will probably not have to earn their living. For them the course provides a convenient stop-gap between school and adult life, in a place where they can learn to grow up pleasantly and happily, while at the same time providing themselves with a form of insurance in case they do have to keep themselves. For them it is also a safeguard against the increasing difficulty of finding domestic staff. Coming from homes where all the housework is done by servants, they realise that for themselves it may be a choice between the cooking and the dusting. The girls who attend Winkfield have plumped for the cooking.

Westernesse in the rain

An Aran Island scene on a sunnier day. This aerial photograph by Aongus O’ Flaherty is from http://www.aerarannislands.ie

My first glimpse of the British Isles was the Aran Islands, at the mouth of Galway Bay, where our trans-Atlantic ship stood off to land a few passengers. It was an emotional moment. The destination of our long sea journey at last become visible. Vague romantic dreams faced with reality. I was shocked by the bareness and bleakness of the landscape. Heavy rain was falling, and wind lashed waves onto the shore. The bare rock of the grayish white hills (karst limestone, I later learned) was dotted with tiny scraps of green that glowed brightly in the rain-sodden air. A few white cottages of plain design: four walls and a pitched roof, a door in the middle and small windows at each side.

In notes written at the time, I tried to capture my sense of the place:

Centuries old, yet timeless. Feeling of age and solidity of a way of life that has gone on for centuries – the grimness of it, the few rewards. Can imagine the people to be tough and dour. Weather-beaten faces of seamen who brought the tender out to pick up passengers. No-nonsense faces, with a wry sense of humour.

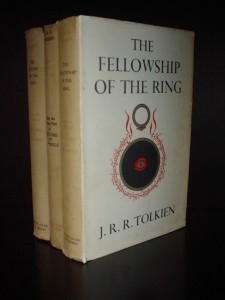

The Lord of the Rings trilogy in its original format as published by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. in the mid-1950s.

From halfway across the world, the reality of the British Isles was also mixed with romantic fantasy. Before we left New Zealand, copies of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, with the device on its cover of Sauron’s eye within the Ring, surrounded by Elvish script, were passing from hand to hand among our friends. As I looked across the sea to this westernmost part of Ireland, I couldn’t help thinking of Tolkien’s Westernesse, the place to which the fairy people set out when life on Middle Earth became impossible for them.

The curtain of rain swept down again. The ship moved on, headed for Southampton, the end of our journey and the beginning of our new life.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

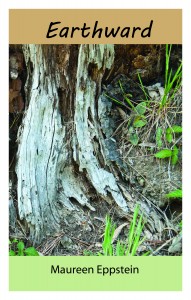

My new poetry collection

I am excited to announce that Finishing Line Press is now taking pre-publication orders for my new poetry collection, Earthward. It can be ordered now and will be printed and shipped in October. You can order online from the publisher at https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

The cost is $14 plus $2.99 shipping. The publisher bases the size of the print run on how many pre-publication orders they receive, so I hope you’ll consider adding to my tally. Please feel free to suggest this book to others you think might be interested too.

The poems in Earthward explore the cyclical patterns of life. Here is a sample poem:

Osprey With Fish

Undercarriage of leg and talon

joins two bodies similar

in sleekness,

twinned

as life and death conjoin

in a continuum

of nourishment.

Huge wings slow over forest,

a fading cry.

I’ve been honored to receive reviews from poets I admire:

With a naturalist’s eye for the precise and sensuous image and a writer’s care for the precise and sensuous word, Maureen Eppstein plants our human griefs into this book, roots them, and invites them to quicken into new life.

—Jane Hirshfield, author of Come, Thief

What captivates me about Earthward is the way Maureen Eppstein transforms ordinary landscapes into miraculous acts of affirmation. Turning compost becomes an opportunity to ponder death and resurrection, braiding garlic reminds us of the “pleasure taken in braiding the hair of the beloved”. This is poetry of quiet lyrical depth, that reconnects us with land and spirit. Earthward invites us to stand deeply rooted in each moment, “in awe and wild surmise at all this human brain can not yet comprehend.”

—Devreaux Baker, author of Red Willow People

In Earthward, Maureen Eppstein unites what would break us with what will bring us back to life. The wild ones, like us, must eat, and so kill. Lost sisters are mourned by proxy. Some things we love are transplanted and transplanted again, surviving and sometimes thriving. The tenacity Eppstein describes is the foundation of our lives. There are those who say that to write about the extraordinary one must look lovingly at the ordinary. Eppstein knows where, and how, to look.

—Camille T. Dungy, author of Smith Blue

Here’s a brief bio:

Maureen Eppstein is the author of two previous poetry collection: Rogue Wave at Glass Beach (2009) and Quickening (2007), both published by March Street Press. Quickening was also first runner-up in the 2007 Finishing Line Press/ New Women’s Voices competition. She has been a finalist in several other book contests. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including Poecology, Calyx, Basalt, Written River, Sand Hill Review, and Aesthetica 2014, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Crossing the boundary between the arts and the sciences, her poems have been included in a textbook on computer graphics and geometric modeling and used in a university-level geology course.

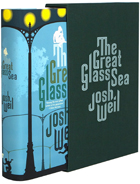

Josh Weil novel launched

I’m so proud of young novelist Josh Weil, whom Mendocino Coast Writers Conference picked as a rising star and invited to be on faculty at our 2013 conference. Here’s news from Josh worth sharing:

literary prize, the most incredible first-edition program I’ve ever seen, my complete book tour schedule—but there are two reasons, above all else, that this issue of The Gazette is a pretty special edition.

literary prize, the most incredible first-edition program I’ve ever seen, my complete book tour schedule—but there are two reasons, above all else, that this issue of The Gazette is a pretty special edition.“[An] impressive debut…As broad as its themes are—touching on political, philosophical and historical divisions—Weil’s first novel is rooted in family and fine storytelling; it’s an engaging, highly satisfying tale blessed by sensitivity and a gifted imagination.”

“A tale of longing and sadness, threaded by Russian folklore and heavy with the weight of love…resplendent and incandescent.”

“A well-timed dystopian tale, the novel beautifully details both the politics of [an] hypothetical Russia—“oligarchs bred beneath the clamp of communism let loose upon loot-fueled dreams”—and its impact on one small family.”

And the first newspaper review (out even before the official publication date!) was even better:

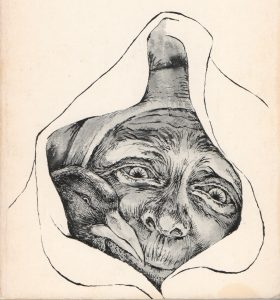

“If complex literary novels really are done for, Josh Weil must’ve missed the text message. His formidable “The Great Glass Sea” knits together strands of traditional Slavic folklore and futuristic speculative fiction to create a passionate reflection on technology and personal happiness. Spanning almost 500 pages, the novel poses mind-bending questions about politics, ecology and the ambivalent closeness of siblings…Weil pulls off dazzling strokes of storytelling…His distinctive voice obliges readers to slow down and swish certain passages around before swallowing…While keeping the sophisticated themes afloat (science vs. nature, the state vs. the individual, family obligation vs. ambition), almost every page flows with respect for the flawed, endearing heroes, Dima and Yarik. Pushing the envelope on literary artistry even further, each chapter begins with a pen-and-ink illustration by the author….A genre-bending epic steeped in archetypal stories, “The Great Glass Sea,” rises above the usual Cain-and-Abel formula by way of sensitive, resourceful craftsmanship.”

And here’s me, now, signing off and saying thank you, again, for continuing to care about what that tyke’s grown up to love, what the writer he became now does, these words on a page that I am so lucky to be able to share with you.

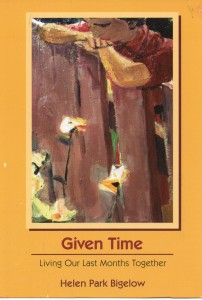

Given Time

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

To offer a flavor of the book, I can’t do better than to quote the blurb by Fithian Press, the book’s publisher: “The book deals honestly with the process of dying, an ordeal shared by both of them. It also deals with the process of staying alive and in love until the ordeal is over… [Bigelow] writes with brutal honesty about her anger and grief over what has become of her husband and herself. The book isn’t a manual about how to take care of a dying man, but it makes the reader well aware of what a grueling job it is. “So this is it,” she writes. ‘This chemo routine is the rest of our lives together…and goddamn it, it’s going to be as good for both of us as I can make it.’ ”

Reading this book set me to thinking about my husband’s and my circle of friends. We’re all of an age where we’re facing mortality, both our own and our partners’. Physical infirmities creep up on us. Memories start to fail. The mechanisms of the heart become clogged. I know we’ll all do what we have to do, to the best of our abilities, when loved ones need our care, and that, if we are the ones whose lives are ending, we hope to have someone as caring as Helen to tend our passage. I’m grateful that services such as hospice are available. Most of all, I am inspired by Helen’s love of beauty to seek it out in my own life. Whether my time is counted in decades or years or even months, I want every day to be touched by grace.

Texts

Searoad, a story collection by Ursula K. LeGuin, has a permanent place on my bedside table. It’s there because every now and then I need to reread a certain story. A very short story, less than three pages, it is titled “Texts,” and tells of an older woman who, bombarded by messages and calls to action, retreats to the coastal Oregon village of Klatsand for a month-long winter break. As she walks on the deserted beach, she notices that the waves have left messages in the lines of foam, messages she can almost decipher. The laciness of the foam leads her to speculate that crochet work and lace might also be legible. In a handmade lace collar she reads a message that seems directed to her: “my soul must go, my soul must go … sister, sister, light the light.” There the story ends, with the woman not knowing “what she was to do, or how she was to do it.”

I think of this oddly moving little story every time I walk on Ten Mile Beach, as I did last Sunday. The receding waves left undulating lines of bubbles, iridescent in the hazy sunlight, that popped to form patterns of foam. Scattered across the beach were strands of bull kelp, dried into coils and loops that lay like a cursive script on the sand.

Yesterday, when the wind was brisk and the sea streaked with white caps, I remembered an interview I did for the Mendocino Art Center magazine. It was part of a series I wrote on artists who helped found the art center in the 1960s. By the time I met Jim Bertram in the early 2000s, he was senile and nonverbal, so I had to rely on material in the art center archives for information about his background and artistic vision. Nevertheless, Jim and I spent a wonderful afternoon together. I think a poem I wrote at the time sums it up:

MESSAGES

For JB

“Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.”

– Jim Bertram

These bright spring days, when the wind

scribbles its white calligraphy

on a wash of aquamarine,

I think of the artist in his studio

upstairs of a weathered storefront

overlooking Mendocino Bay.

Sheet after curling sheet he showed me, canvas

after canvas, covered with calligraphic forms

that could have been words, but were not.

In our shared silence I understood his drift:

how sometimes what matters most is inarticulate:

like the line of spray from a lifting wave,

the hand of an old man painting messages of love.

On my way downstairs from Jim’s studio, I fell in love with one of his paintings, which now has a place of honor in my house. I smile when I read its message.