Archive for the ‘nature’ Category

Death of a Christmas Tree

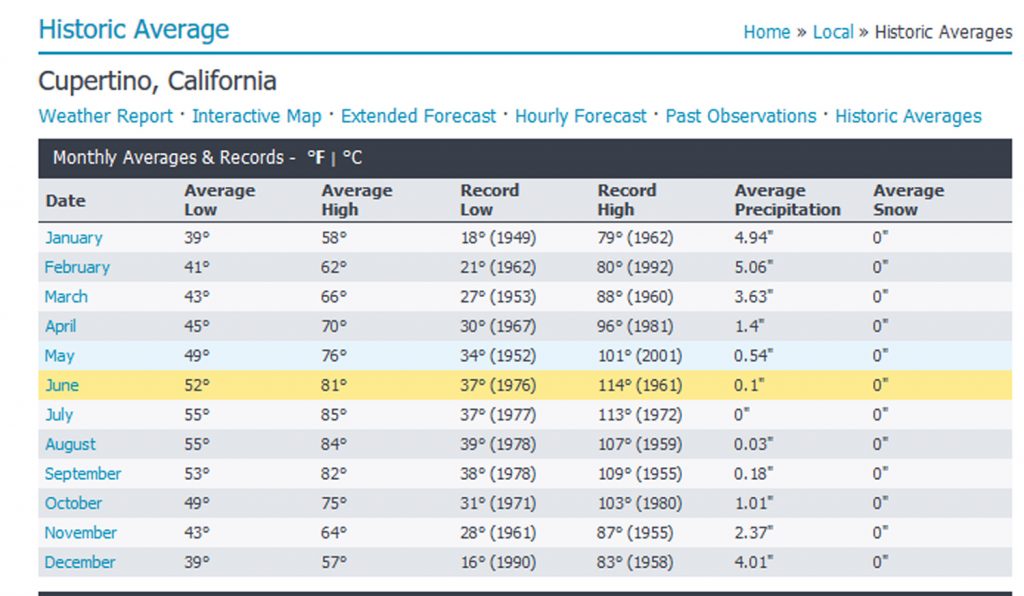

We’d bought the young spruce in a fit of environmental consciousness when we still lived in Cupertino, CA. and it served as our Christmas tree for several years. In 1973 it survived our move to Santa Barbara, carefully bolstered in the U-Haul truck so it wouldn’t get smushed. It put up with a year or so of Santa Barbara sunshine, had even come into the house one holiday season. But that year, 1975, the temperature spiked into the 80s just after Christmas and hot sun streamed into the house. I was too busy with holiday guests and activities to think about moving the tree outside into the shade, so it stayed inside far too long. By the time we disburdened it of its decorations and lugged it back outside, the damage was already done. Months later, when I could no longer bear to look at pathetic brown needles, I removed it from its pot. The roots were tightly bound around each other.

One received wisdom is that you buy a potted tree for the holidays, then plant it in your garden. But this is not realistic if the tree’s grown size will overpower existing plantings, or if its natural habitat is elsewhere. I found a curious example of this when a few decades later we moved to Mendocino. In the patch of native forest on our property I found two trees with silvery needles. A naturalist friend identified them as some kind of spruce, definitely not native. She told me the story of how they most likely got there. The original developer had been hauled into court for illegally logging the property to create a “view development” and was ordered to replant. She speculated that he picked up a job lot of leftover Christmas trees to fulfill this requirement. Our two spruces, crowded out by redwood and Douglas fir, did not survive much longer.

So what to do about a Christmas tree? Over the years we’ve tried various approaches. We’ve gone to cut-your-own tree farms. But sawing into a young tree felt like committing murder. We’ve bought a cut tree from a lot and kept it outside in a tub of water for as long as possible. Even so, it would be shedding needles even before it came into the house. It would have been been cut weeks before, and shipped hundreds of miles from where it was grown. We’ve thinned out young firs from our own property. But they’ve been spindly little things, too likely to topple.

For the past couple of years, we’ve not bothered with a tree at all. I’ll maybe clip some low-hanging conifer branches to make a big arrangement in a bowl on the dresser or a wreath for the door. But that’s about it. I like my trees living. Like this baby Grand Fir that workers clearing a drainage channel a few weeks ago rescued from an overgrown coyote bush and saved for me.

Sitting down with lions

In many cultures, humans see themselves as siblings to other living beings. In Aotearoa New Zealand, where I grew up, the Māori people recognize landforms such as mountains and rivers as their relatives. Even in Western Judeo-Christian societies, where humans are believed to have been make in God’s likeness and to have dominion over all creatures (Genesis 1:26), people with beloved domestic pets may discover that their relationship is closer to that of peers than of master and subject.

My own views, which come closer to those of scientific pantheism, had a formative moment one summer day in the early 1970s, when my friend Judi and I took our children to the Oakland Zoo. I tell about it in a letter to my parents:

A lion cub recently born at the Denver Zoo. Image from the Denver Post.

The biggest thrill of the day, I got to cuddle a lion cub. Little 7 week-old roly-polies, they had been separated from their mother – I gather the father was threatening to harm them in the cramped quarters of the adult lions. We happened to be there at bottle time, and the keepers brought them out to a low platform in the children’s zoo. They obviously need lots of affection. I was sitting on the platform, and one of them just crawled into my lap, like a kitten or a puppy.

I will remember always the roughness of the cub’s fur under my hand, the warmth of his tiny body, the loudness of his purr, the overwhelming sense of awe that this wild creature trusted me. Here’s a poem about the incident:

The Lion Cub

In the dusty heat of the zoo

a lion roars.

I conjure a dream of Africa

an endless veldt

an alien majesty

concealed in yellow grass.

At the petting zoo

three lion cubs

explore a patch of dirt.

I sit.

One crawls into my lap

nuzzles my hand.

Under thick baby fur

muscles ripple, relax

curl up for a nap.

Wide-eyed, the children watch

and touch.

Distance evaporates.

We are earth family

connected deep in time

in mother love.

Making acquaintance with snakes

Growing up in Aotearoa New Zealand, a country with no native snakes, I never learned the phobia many people have about these creatures. Since moving to California I’ve learned to keep rattlesnakes at a respectful distance, but can only listen, fascinated, as friends tell stories of the poisonous slithery ones of their childhoods.

Our family had a fine introduction to the harmless garter snake in 1972, when we went camping at Big Sur during spring break. I tell about it in a letter to parents:

27 April 1972

We had a lovely trip to Big sur. The coastline there is really spectacular – a romantic tumble of cliffs and waves, with the highway carved out of the side of the cliff. …The campground is back in the valley of the Big Sur River, a lush, green, woodsy place, with the river bronze-gold over its boulders. We camped right on the edge of the river, and as you can imagine the kids [our two plus their friend Mark, ages nine, eight and seven] had a ball messing about in the water. … Lots of wildlife for us to observe. One day, coming back from the beach at the mouth of the river, we met a man who had caught a huge garter snake, and was taking it home to his daughter, who collected reptiles. Both he and the snake were very obliging about letting the kids play with it and handle it, and it was a very contemplative, envious trio that walked back across the river meadow where he had found it. It’s interesting to observe the effect of the nature programs they have attended on these kids. A lot of emphasis is put on the phobias and misconceptions that many people have about snakes. The children learn how to watch out for rattlesnakes, but they also learn to value the many other useful and beautiful snakes we have here. Following their example, I even held a snake for the first time, a baby Santa Cruz garter snake that Tony had found by the campsite. A pretty little thing, striped lengthwise yellow and black, and warm and wriggly in the hand.

We have had other snakes in our lives. In Santa Barbara, where we lived in the late 1970s, a huge king snake took up residence in our garden. Since king snakes eat rattlers, we were happy to make it welcome. Less welcome were the pair of caged garters one of our sons and a visiting friend brought back in guilty triumph from a local pet shop. My son assured me that he would be responsible for feeding and taking care of them. Yeah, right! Fortunately, both snakes managed to escape within a few days.

Here on the Mendocino Coast I often see garter snakes, either on a walking trail or in the garden. I have learned to live with the cycles of nature that make them both predator and prey. Here’s a poem about that:

Learning Detachment

Mirror black, raven on the wall

lifts limp coils of garter snake

its skin striped red and brown

in intricate pattern like a carpet

loomed in some ancient sunlit place

maybe the same snake I saw

near where a tree frog

shiny as sun on a wet spring leaf

leaped into shadow

sadness for lost beauty

rises and dissipates

the snake has eaten

the raven eats

How we came to live in Mendocino

We’d never been camping before as a family when, in the summer of 1971, Tony and I decided to take our children, then eight and five, on a short trip to explore some of the northern part of California. On our return, I wrote an ecstatic letter to my parents:

The beach at Russian Gulch State Park, looking under the bridge to the sea. Image by David Eppstein, Wikimedia Commons.

25 August 1971

I guess I haven’t told you about our camping trip. We had a marvellous time, and are really sold on camping. We hired a 9×9 tent, and bought a pup tent for the boys, a propane stove and lantern, and a very nice ice box, so we were pretty well set up, and the state park campgrounds are really very civilised, with your own picnic table and food cupboard, and running water, bathrooms and showers not too far way. We spent five nights at Russian Gulch, which is on the Mendocino coast, about 200 miles north of here. This really is a delightful spot. The sea coast here is very rugged, with steep cliffs and caves and tumbled rocks, and grassy meadows on the headlands, with pine and redwood forests behind. The gulch is made by a lush little creek that flows into a tiny cove, making a perfect beach for the children, and the campsites are straggled along the edge of the creek, sheltered from the sea wind, and with a view of redwoods high above you. The weather was beautiful – only a trace of fog a few mornings, and it can be thick all the time. The children got very used to going for long walks, and we also spent a lot of time just sitting and unwinding and watching the wildlife – lots of jays, rabbits, chipmunks and garter snakes. The anchovies were running in the cove, so thick they were being hauled in by waders with nets, and of course they attracted the bigger fish. We were sitting on the beach one afternoon when a group of scuba divers came along with a huge catch, and offered us some, so we had fresh cod for supper.

After describing our impressions of Mendocino village – “splendid weather-beaten old buildings, many of them fine examples of carpenter Gothic, very similar to New Zealand colonial period architecture” – the letter continues:

From Russian Gulch we went on up the coast highway then inland to the Humboldt Redwoods. These are very lovely and impressive, but I think our hearts were still at Russian Gulch.

Here’s where the story takes a mythic turn. Here’s how I tell it now:

Once upon a summer afternoon a man and a woman sat on a beach. As the couple sat and gazed, a young man emerged from the sea. He was beautiful, with golden hair that hung to his shoulders and a body that had known good exercise. From each of his hands hung a fish, whose scales shone wet and silvery.

The woman called out, “Nice catch!” to the fisherman as he passed.

He paused. “Would you like one?”

The woman’s fingers flew to her blushing face. “Oh no, no, I didn’t mean …”

The fisherman lingered. “Please. I have more than I need.” He held out one of the fish.

The man sitting with the woman rose slowly to his feet. The fisherman placed the fish in his out-stretched hands. The man bowed his head and murmured his thanks. That evening, the man and the woman cooked the fish over their campfire and ate its sweet flesh.

After the man and woman returned to the city, every now and then they would feel a tug, as if they were being played on an invisible line. They would say to each other, “We need to go back to that place.” So they would rent a house on the coast for a week or two. The sea sang to them, and each evening a golden light would seep like an enchantment across the drowsy headlands. When their time was up, they would return sadly to the city.

In this way thirty years passed. Each year the tugs grew stronger, the city more and more unbearable. At last they could resist no longer. They left the city. In a house close to where they had eaten the fish, where the scent of the sea came to them, they quietly lived out their days.

The Easter Bunny mystery

How could my husband and I be so mean as to deny our kids the Easter Bunny? I frowned as I reread the letter to my parents stashed in my old black filing cabinet.

12 April 1971

The kids are back at school today after their week of Easter vacation. The weather has been so beautiful and spring-like. This is something I couldn’t really understand until I came to the northern hemisphere—the significance of Easter as a spring festival—the death and rebirth of the god that is an important part of almost every religion there has ever been. Here a big thing at Easter is the Easter Bunny, who is alleged to bring baskets of candy eggs and goodies to kids on Sunday morning. This Tony and I just can’t go along with—somewhat to the kids’ disappointment, I think, though we do buy them a fancy Easter egg, and of course we have the fun and mess of dyeing hard-boiled eggs and hiding them in the garden for an egg hunt. I did allow Simon to share our pet rabbit at school one morning. Bun-Bun was less than enthusiastic about the whole project, but the children were ecstatic.

Part of the reason for our rejection of the Easter Bunny was that Tony and I grew up in New Zealand, where rabbits were despised as pests. Brought by early settlers to a place with no natural predators, their population quickly reached plague proportions, causing major erosion problems. We did have Easter eggs, but given that we celebrated the festival in the Southern Hemisphere autumn, they had no significance other than as a source of sugar and chocolate. Even living in California, we couldn’t see any connection between rabbits and the Christian celebration of the Resurrection. I decided this week to look into the question. I quickly found myself down a fascinating rabbit hole of customs, beliefs, and theories, many of them contradictory.

How the Easter Bunny came to the U.S. seems pretty clear. According to several sources, the creature first arrived in America in the 1700s with German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania and transported their tradition of an egg-laying hare called “Osterhase” or “Oschter Haws” who brought colored eggs to good children at Easter. As the custom spread across the U.S. the hare somehow transformed itself into the more familiar rabbit and its Easter morning deliveries expanded to include chocolate and other types of candy and gifts.

The hare’s (or rabbit’s) connection with Christianity are more complicated. For the first few centuries, the Christian festival coincided with the Jewish Passover, which is when the historical events surrounding Jesus’s death occurred. Though the Christian calendar has since been modified, both festivals are still close to each other in spring. Both are based on a lunar calendar; the date of Easter was defined in 325 CE by the Council of Nicaea as the first Sunday after the first Full Moon occurring on or after the vernal equinox. In Anglo-Saxon regions of Northern Europe, the Christian festival seems to have merged with a pre-existing equinox festival honoring Eostre, the goddess of spring, and Christians continued to use the name of the goddess to designate the season. Since hares and rabbits give birth to large litters in early spring, they have long been recognized as symbols of the rising fertility of the earth at the vernal equinox.

No, no, no, say some Catholic writers. The Easter Bunny has Christian origins. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle observed that the hare could conceive again while pregnant, thus shortening the time between litters and delivering more offspring during a breeding season. Later Greek writers such as Pliny and Plutarch expounded the notion that hares (and rabbits, by association) were hermaphrodite, and thus could self-impregnate and reproduce as virgins. During the medieval period, hares and rabbits began appearing in illuminated manuscripts and paintings depicting the Virgin Mary, serving as an allegorical illustration of her virginity.

Two pregnancies at once? Intrigued, I veer into another passageway of my research rabbit warren. It turns out that, as the Smithsonian Magazine put it, “Aristotle got it right: the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) can get pregnant while it’s pregnant.” In 2010, scientists of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW) in Berlin, Germany, led by Dr. Kathleen Roellig, published the results of their study. Using selective breeding and high-resolution ultrasonography, they showed that a male hare can fertilize a female during late pregnancy. The resulting embryos will develop around four days before delivery of the first pregnancy. To quote from the Smithsonian article: “The embryos don’t have any place to go at that time, however, since the uterus is occupied by the embryos’ older brothers and sisters. So the embryos hang out in the oviduct, rather like when you wait in your car for a parking space to open up. Once the uterus is free, the embryos move in.”

My head is spinning. I think I need chocolate.

The way we learn to belong

Once more we are at that seasonal turn familiar in California history: after a winter of great rains, floods and mudslides, the promise of an extraordinary blaze of color as wildflowers burst into bloom. My first experience of this magical transition was in 1969, my second spring in this new country. I describe it in letters to parents:

Feb. 28, 1969

It has actually stopped raining for the past hour. Another shower on the way, of course, but such a respite to see the sun. We have been averaging one sunny day a week for the past two months, and the general situation is already critical. We are not doing too badly in the Santa Clara Valley. All the creeks are contained by reservoirs up in the hills, and although the largest one, Anderson, is spilling over the top and flooding parts of east-side San José, the others are still holding their own. Fortunately the weather-man had predicted a respite for the next four or five days, i.e., drizzle instead of a deluge, and the authorities are hoping to get enough water away through the sluices of the other six dams during this time to make room for next week’s storms. Where we live is on relatively high ground anyway, so it is unlikely that we would be affected. The really big headache though is Central Valley, which drains the whole of the Sierra Nevada range. The Sacramento-San Joachim delta has flooded twice already in the past two months, and the river levels are still dangerously high. But in the high Sierra the snow fall is already twice the annual average, and we are only one third through the rainy season. Sooner or later that stuff is going to thaw, and if there is a warm rain up there, the effect will be sudden and disastrous. Meanwhile, it is still raining, with violent storms rolling in from the Pacific with tedious regularity. For some vast meteorological reason, the storm belt has swung further south than normal this year—so we are getting what Alaska usually gets. (They say it’s a mild winter in Alaska this year!)

A field of mixed wildflowers: Arroyo Lupine, Baby Blue-eyes, Purple Owls Clover and Tidy-tips. Image from Mother Nature’s Backyard.

And a few weeks later:

April 14, 1969

[After a visit to the Lick Observatory on Mt. Hamilton] We decided to see what it was like on the other side of the mountain. We found ourselves in a charming little valley, the San Antonio, which we followed back to Livermore and the freeway home. The land in this part is lightly wooded, and very sparsely populated—we saw a few ranch houses, occasional small herds of cattle, the odd horseman and dog, and that’s all. And at this time of year, the earth between the trees is covered with fresh grass, so scattered and strewn with wildflowers that it looks like some magic carpet.

I think it is one of the most wonderful sights I have ever seen. Great swathes of colour, of every shade. One they call Sunshine, or Goldfields, a tiny daisy-like flower, brilliant yellow. It grows only a few inches high, but in such profusion that, as its name implies, it makes a great field of colour. And on the slopes of Mt. Hamilton we thought for a while the snow was still lying, there were such patches of a snowy white flower. But other colours too, pinks and blues right through to the purples and reds. And down in the lower valleys, the California poppy, a brilliant orange. …I love these flowers so much.

An interviewer recently asked me what moved me toward writing about nature. I replied that as an immigrant, learning about the land was a big part of learning to belong to my adopted country. I’ve found this be particularly true when I moved from the Bay Area to the Mendocino coast. I’ll always be grateful to Dr. Teresa Sholars, whose College of the Redwoods wildflower identification class gave me the names of beloved beauties. Here’s a poem about them:

California Wildflowers

It seems a simple joy

to greet the flowers by name

Tidy Tips, Goldfields, Blue-Eyed Grass,

Crane’s Bill and Cream Cup,

Sticky Monkey Flower,

Mule’s Ears, Owl’s Clover,

Sun Cups glossy by the path,

Milkmaids in shade,

Lupine and Poppy on the slope,

but to the immigrant who after 40 years

still speaks with foreign intonation,

these are pet-names for familiars

precious as friends,

who speak in a language without words

of soils: clay and serpentine,

of rains and drought,

the way the lineaments of the land

impress themselves,

the way we learn to belong.

In a couple of days I’m off to Portland, OR for the Associated Writing Programs (AWP) conference. I was invited to be part of a group representing Scarlet Tanager Books, publisher of the anthology Fire & Rain: Ecopoetry of California, in which I have several poems. We’re hosting a reception at the conference, and doing a reading at a neighboring bookstore. Being recognized as an “ecopoet of California” makes me feel that, after what is now 52 years, this beautiful state is home. Enjoy this season’s flowers.

The turning of the year

Here we are at the turning of the year. It’s been a hard year in many ways. My particular concern has been the environment and natural resources. I’ve had to witness oil and gas interests take precedence over the protection of fragile landscapes, sacred cultural resources and vulnerable water supplies. Wildfires have devastated Northern California, where I live, including parts of Santa Rosa, the city where we go for many services. A huge fire now threatens Santa Barbara, in southern California, where I lived in the 1970s. Here on the northern coast, warming ocean temperatures have wrought havoc on the kelp forests and the sea creatures that depend on them. Throughout the world, as starving people flee drought-stricken lands, tribal hostilities are increasing.

Meanwhile, the days follow each other. The sun’s arc rises lower and lower in the sky, its rising and setting further and further to the south, and the darkness of longer duration. There will be a pause, a solstice or sun-standing-still, and then a return of the light, and we will celebrate, in our various spiritual traditions, a return of hope.

May you all find hope and joy in the days to come.

A tale of a sparrow

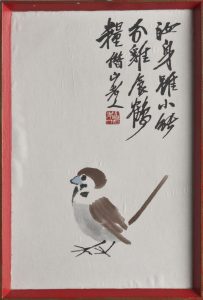

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

In the late 1950s, when my husband Tony was a student, he strolled into a junk shop in the small town of Hawera, New Zealand. A charming image of a sparrow caught his eye. Fast forward ten years. Tony was by then an engineer at a high tech company in Silicon Valley. The sparrow pops up again in a letter I write to parents:

14 April 1969

A friend of Tony’s from Memorex came to dinner. A Korean boy … He is really charming, and we had a pleasant evening. One interesting thing that came out of it – Yun also reads and writes Mandarin Chinese, so was able to translate the inscription on our sparrow picture for us. Do you remember our sparrow? It is a little brush drawing that Tony picked up in a junk shop in Hawera when he was a student, shortly before reading in a magazine a story about a famous Chinese artist who was objecting to a government campaign to kill off the sparrows to improve the wheat production. He made these little posters, inscribed with sentimental stories about the sparrow. And this, as far as we can tell, is what we have got.

With the help of the Internet, I’ve been piecing together my fragments of knowledge about this period in Chinese history. What I discovered is a familiar story about well-intentioned interference with nature leading to ecological disaster.

In the First Five-Year Plan of the newly-founded People’s Republic of China, families were each given their own plot of land. In the Second Five Year Plan, begun in 1958, a new agriculture system was announced. Family farms were grouped into collective farms, making each village a single production entity in which everyone would have an equal share. Food would be provided in a communal kitchen.

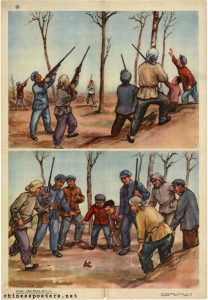

In theory, a collective farm where resources were centrally controlled should be more efficient and yield higher productivity. In practice, agricultural production figures fell. Food shortages were exacerbated by flood and drought. Believing that getting rid of sparrows, who ate grain, would improve production, Chairman Mao Zedong launched the Four Pests Campaign, which encouraged citizens to kill them, along with three other pests: rats, flies, and mosquitoes. Sparrow nests were destroyed, eggs were broken, and chicks were killed. Many sparrows died from exhaustion; citizens would bang pots and pans so that sparrows would not have the chance to rest on tree branches and would fall dead from the sky. Citizens also shot the birds down from the sky. These mass attacks pushed the sparrow population to near extinction.

In hindsight, the result was inevitable. Too late, Chinese leaders realized that sparrows didn’t only eat grain seeds. They also ate insects. With no birds to control them, insect populations boomed. Locusts, in particular, swarmed over the country, eating everything they could find, including crops intended for human food. People, on the other hand, quickly ran out of things to eat, and tens of millions starved.

Night of the cane toads

I recently asked my son Simon, now in his fifties, if he remembered anything of our visit to New Zealand when he was two. He thought for a moment. “I remember the frogs.” Ah yes, the frogs. Actually they were cane toads, but a two-year-old doesn’t bother with such distinctions.

Our flight from San Francisco to Auckland had a six-hour layover at Nandi, Fiji. When we arrived in Nandi at 4:00 am, we learned that the airline had very kindly provided a motel room so that we and the children could get a little rest. Tony and I looked forward to this. We were flying Qantas Airlines, and a bunch of young Australians partied all night in the rows behind us, oblivious to the flight attendant’s efforts to keep them quiet. The children, however, would have none of this going-to-bed nonsense. Their circadian rhythms completely out of whack, Simon and his brother were bright-eyed and ready for adventure.

We heard the toads first, a continuous high-pitched purring that filled the warm tropical night like the sound of a smoothly running motor boat. Then we saw them. Near the motel swimming pool stood a pole with a bug-zapping lamp attached. On the ground below, hundreds of cane toads clustered, waiting for the next flying creature to drop. The children were enthralled. Fortunately we did not allow them to go near the creatures, who can secrete a toxic poison.

The cane toad (Rhinella marina) is native to South and Central America. In 1935 they were introduced to Fiji and other places to control beetles on sugarcane plantations. The trouble was, the toads couldn’t jump high enough to eat the beetles, which live on top of cane stalks. With no natural predator in their new home, the cane toads bred in large numbers, and have proved to be an environmental disaster. They have voracious appetites, and will feed on almost any terrestrial animal and compete with native amphibians for food and breeding habitats. Their toxic secretions are known to cause illness and death in wildlife and in domestic animals that come into contact with them.

The cane toad disaster is a classic example of humans disturbing an ecological balance, inadvertently creating a new problem as they try to solve an existing one. Thinking about that tropical night makes me realize how little we still know about the complex interactions of the natural world. But on a personal, selfish note, the Fiji motel toads did provide entertainment for two rambunctious little boys.

The rain in Camelot

When I arrived in California from England’s green and rainy land, I thought I must have landed in Camelot. Remember that song from the 1960 Lerner & Loewe musical?

The rain may never fall till after sundown

By eight, the morning fog must disappear

In short, there’s simply not a more congenial spot

For happy-ever-after-ing than here in Camelot

It rained for a week or two after we arrived, from late May into early June. My new neighbors kvetched, “Enough already!” After a normal rainy winter, early spring had been dry. Now the rains had started back up, and they didn’t like it. I, however, was enchanted. It truly only rained at night; the days were warm and sunny.

Eventually the rain stopped. Grass on the hills turned from green to gold. I had learned about Mediterranean climate in geography class at school: how it occurs only in five parts of the world, on the western sides of continents, between roughly 30 and 45 degrees north and south of the Equator. How it is associated with rotating high pressure zones that migrate through these sub-equatorial latitudes depending on the angle of the sun, bringing clear skies in summer and moving equator-ward to allow frontal cyclones to bring rain in winter.

A classic California landscape: Mt. Hamilton, to the east of Cupertino. Image from http://www.pleinairmuse.com/

Now I was living this rare climate. Warm sunshine day after day. Golden hills faded to a dusty tan. As summer crept toward fall, I found myself longing for the rain and dark I had hated in England. I discovered that my neighbors, too, eagerly awaited the first rain of the season. We celebrated together as the sky darkened and the first drops fell. I was learning to be a Californian.