Archive for the ‘nature’ Category

A cool way to help restore a forest

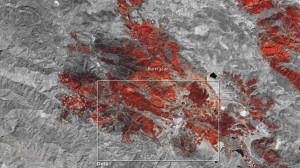

In neighboring Lake County this past summer, wildfire destroyed 76,000 acres of forest (about seven million trees) and nearly 2000 homes, businesses and other structures. Mendocino Coast Botanical Gardens has stepped up with their Lake County Giving Project. One component of the project encouraged people to purchase potted trees and other plants for their holiday decorations, then bring them back to be donated to Lake County residents rebuilding their homes.

Zoomed-in false-color shortwave infrared satellite image showing the Valley Fire burn scar near Middletown, California on September 20, 2015. Burned areas appear orange or dark red. (NASA Earth Observatory)

The other component of the Giving Project is seed balls. With advice on plant species from the USDA Resource Restoration Project and the Natural Resources Conservation Service, Wild Jules is crafting seed balls of wild grasses, perennials, and annual wildflowers for habitat restoration in the fire-ravaged areas. According to the Wild Jules website, “Individual varieties of seed are proportionately mixed with red clay and compost to provide a self contained method of spreading native varieties. The ball protects the seed from birds and rodents. The seed cannot dry out or blow away. The best part is, you can cast these ‘jules’ (jewels) out on top of the soil any time of year. The seed within the clay balls will wait patiently to germinate until adequate water is applied by way of rain or irrigation.”

A Wild Jules seed ball. The balls being prepared for Lake County habitat restoration are a little more flattened so that they stay put on steep hillsides.

Tony and I were intrigued enough to stop by the Garden Store to donate a few dollars to the seed ball purchase fund.

Julie Kelly, founder of Wild Jules, says: “It’ll take many years but every bit counts. The perennials won’t bloom this year, but the annuals will. They will help feed foraging insects and birds and lift the spirits of the folks so terribly impacted.”

Rooftop solar panel program at risk

I’ve just done my citizen activist stint for the week: fired messages to the California Public Utilities Commission, Governor Brown, and my state assemblyman and senator regarding a proposal by big utility companies to gut the rooftop solar panel business by increasing infrastructure fees and drastically reducing the credit solar panel owners get paid for releasing the surplus electricity they generate. It seems that letting consumers generate their own electricity is cutting into big business’s profits. The CPUC is expected to make a decision by mid-December.

Here’s what I wrote to the CPUC. If you’re interested in adding your voice, you can find more information at:

http://mendocinosolar.com/ (our vendor)

http://www.saverooftopsolarca.com/

TO: California Public Utilities Commission

In this time of global climate change, I urge you to reject a proposal by utility companies to gut the solar “net metering” program by increasing infrastructure fees and severely reducing the credit solar panel users earn by selling their daily surplus to utility companies. The utilities’ proposal privileges company profits over responsible citizens’ response to the challenge of global warming.

When my husband and I had solar panels installed on our house nearly two years ago, we contracted with PG&E to pay a monthly service fee, which we assumed was based on a reasonable calculation of our share of infrastructure costs. We also contracted to sell back our excess power at a reasonable market rate. If allowed to charge excessive fees, and/or short solar panel owners as vendors of electricity, PG&E and other utility companies will not only discourage other people from installing rooftop solar systems, but also discourage users of existing solar panel installations to be frugal and responsible in their use of electricity, since there will be no incentive to conserve.

The issues raised by global warming are so huge that we cannot allow any backsliding on conservation. Again, please reject the utility companies’ proposal.

Love of Place

This week I learned a new word, soliphilia, which means love of place. I’m inviting you to read a beautiful essay about place by my friend Sharman Apt Russell, who lives near the Gila National Forest in New Mexico. She starts:

I walk out of my house onto a country road. If I go north two miles, I’ll be in the Gila National Forest, 3 million acres of pure New Mexico: ponderosa pine, pinon pine, scrub oak, juniper, yucca, prickly pear. The names of familiar species are like the beads on a rosary: mountain lion, black bear, javelina, coati. If I walk south five miles, I can turn onto Highway 180 and find my way to anywhere, Dallas or Paris or Bangkok. By God (and here comes my first imitation of Walt Whitman) I live in the best of places!

Click here to read on, and enjoy her lovely pictures.

Cycles of life

This week’s post is reprinted from the Arts & Entertainment section of the May 29 Palo Alto Weekly. Henri and I are very excited about our upcoming reading.

Cycles of life

Two poets return to Palo Alto for shared reading

by Elizabeth Schwyzer / Palo Alto Weekly

Poets and friends Henri Bensussen, left, and Maureen Eppstein will read their work in Palo Alto on Friday, June 5, at Waverley Writers. Photo by Tony Eppstein.

“My friend’s body is a brown leaf,” writes Maureen Eppstein in “Going Dark,” a poem from her recent chapbook, “Earthward.”

” … the fierce flame of her will/refuses surrender./ It’s not death’s darkness she resists/but the loss of a self transfixed/by what is beautiful.”

That same enthrallment with life she witnesses in her dying friend is evident throughout Eppstein’s collection of 26 poems. Beguilingly simple, founded in close observations of nature, these poems unfurl to reveal the writer’s keen sensitivity, sense of humor and clear acknowledgment that every life ends with death.

On Friday, June 5, the former Palo Alto resident and Stanford University employee will return to town to read from her new collection. She’ll be joined by fellow poet Henri Bensussen, also formerly of Stanford. Both longtime attendees of Palo Alto’s hallowed Waverley Writers — a free, monthly poetry reading founded in 1981 — Eppstein and Bensussen separately retired to Mendocino County, where they’re each active in the writing community. Their Palo Alto visit marks more than 15 years since their departures — Bensussen and her partner left the region in 1999, Eppstein and her husband in 2000 — yet both are well-remembered by area poets.

Janice Dabney, who shared a writing group with Bensussen and Eppstein and worked alongside Eppstein both on the Waverley Writers Steering Committee and at Stanford, spoke of both writers as “very good people” and recalled not just Eppstein’s poetry but also her humanity.

“She was very supportive of me being a gay person,” Dabney recalled. “She made a point of putting her money where her mouth is, which is a good summary of Maureen: She’s not a person who sits idle and spouts philosophies; she gets out there and acts and makes the world a better place.”

Those on the Mendocino Coast speak in equally glowing terms about both women and their work. Norma Watkins, secretary of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference and creative-writing instructor at Mendocino College Fort Bragg campus, explained of Bensussen, “Henri was my student in the past and writes this delightfully quirky prose and poetry. She has a very odd and wonderful imagination so that when you begin reading one of her poems, you never know where it’s going to go.”

Director of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference, Karen Lewis, said of Eppstein, “You can tell from her work that she has a daily, connected presence in nature. Her nature metaphors are especially remarkable.”

Lewis also described a new project of Eppstein’s: a collection of short essays based on her youth in New Zealand and her immigration to the United Kingdom. Those essays can be found at maureen-eppstein.com.

Bensussen, too, mines her own past for material. In “Chimney Rock,” a poem from her new and first chapbook, “Earning Colors,” birds of prey serve as metaphors for partnership and a departure point for a meditation on separation and divorce:

“Peregrine falcons nest in a hollow/under the cliff’s rim. They mate/for life, unlike us or elephant seals.”

Later, she shows herself, standing alone as birds swoop overhead:

“Vultures hunt the dead, veer close/when they notice me. I stare them off. Pose — /Still Life: Woman in Love, Once.”

Both Bensussen’s “Earning Colors” and Eppstein’s “Earthward” are published by Finishing Line Press, a small publisher based in Georgetown, Kentucky. Bensussen explained that she entered the manuscript in a poetry contest with Finishing Line, and though she did not win, they offered to publish the chapbook anyway.

As for the collection’s title, “When you send in a poetry manuscript, it has to have a thread or theme,” she explained. “I realized I had quite a number of poems centered around the idea of color.”

Like Eppstein, Bensussen has a deep connection to nature, one fostered by her studies in biology and many years of birding and gardening. Upon moving to Mendocino, she explained, “I became immersed in the natural history of the area, and also fascinated by how people interact. Often, someone says something and it sends me off on a poetic journey.”

“Earning Colors” is full of evidence of such journeys. Friends’ stories and strangers’ cast-off comments pepper the collection, giving the sense of a writer moving through a crowded room, picking up on snippets of conversation. In “Blood Test,” it’s an “overly friendly” nurse whose question about the origins of Bensussen’s name sends the writer into reflections on “disruptive history,/as tubes fill with dark pulses of my life.”

Life and death draw close in both Bensussen and Eppstein’s work.

“Earthward,” Eppstein’s third poetry chapbook, is “really about the cycles of life and death,” she explained. “It’s centered around the poem ‘Going Dark,’ which was written for a friend in New Zealand as a memorial. She suffered from multiple sclerosis for 40 years, gradually losing more and more of her use of her limbs. Toward the end of her life, we would have conversations about how she was afraid of losing the self that could be moved.”

The self that can be moved is on full display throughout “Earthward,” and the scenes that move the poet are often those drawn from nature. In “Osprey with Fish,” Eppstein writes with simple power of three lives: the bird, the fish and the woman who watches their flight:

Undercarriage of leg and talon

joins two bodies similar

in sleekness,

twinned

as life and death conjoin

in a continuum

of nourishment.

Huge wings slow over forest,

a fading cry.

“Earning Colors” and “Earthward” are available at Books Inc., Town & Country Village, Palo Alto, and online at finishinglinepress.com.

What: A reading by poets Maureen Eppstein and Henri Bensussen

Where: Waverley Writers, Palo Alto Friends Meeting House, 957 Colorado Ave.

When: Friday, June 5, 7:30 p.m.

Cost: Free

Info: Go to tinyurl.com/l4lvwgh or call ![]() 650-424-9877.

650-424-9877.

The Language of Plants

Have you ever wondered whether trees talk to each other about what’s going on in the forest? Can they show compassion or motherly love? Do they team up to ward off an attack?

Recent research has shown that plants communicate using an electrochemical “language.” Taking a break from exploring my old black filing cabinet, I’d like to share a poem about this discovery. It’s from my new collection, Earthward, available from Finishing Line Press.

The Language of Plants

We who move about are at a loss.

We do not know what words to use

for speech that has no metaphor

in the human tongue.

We have ways to speak of learning,

words for memory, decision-making words.

We speak of synapses of neurons in our brains,

name the organs that receive our senses—

ears, eyes and noses, taste buds, fingertips—

words all based on human forms.

The standing-still ones

message their pheromones into the air:

Aphid invasion. Deploy toxin defenses.

Send for the predator wasp to counter-attack.

Roots zing with electrochemical charge

as through their internet—

a mycorrhizal tangle of yellow threads—

they share resources with their kin,

and even with neighbors of other ilk:

Fir borrows summer sugar from birch,

pays it back in the time of barren twigs.

We need new definitions to embrace

the beings who feed on light

not in some alien galaxy

but close at hand:

Does intelligence mean to have a brain

or problem-solve?

New ways of standing in a bean patch

or a forest grove

in awe and wild surmise at all

this human brain can not yet comprehend.

Other people’s weather

An ethereal music filled the air as Tony and I stepped down from the Greyhound bus at Niagara Falls in March 1962, a music so sweet and high it seemed to come from some magical place. I gazed about me. Nothing but bare trees and an almost empty parking lot. A wind that stung my ears. Then I saw them: icicles, many inches long, hanging from every twig and tinkling against each other with every gust.

Growing up in the subtropical north of New Zealand, I did not see snow until I was an adult. Our winters had heavy rain and an occasional frost, enough to whiten the grass and form thin sheets of ice on puddles. But nothing like this: the gigantic falls themselves half frozen and the temperature the coldest I had ever known. Historical records tell me it was probably about 30°F. (though the wind chill factor would have made it seem colder), and that the winter was pretty much a normal one.

We had broken our journey from New Zealand to England in New York to visit my elder sister, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University. As we rode the Greyhound bus upstate to Syracuse, what fascinated me as much as the landmarks my sister pointed out were the piles of dirty snow everywhere. I began to comprehend the northern hemisphere stories I had grown up with, where winter was a time of death and darkness, the weather something to be feared, and the spring thaw a time of great rejoicing.

Having recently passed through the tropical miasmas of Panama, I was also discovering that people could learn to live in places where the climate was not friendly, though the strategies they used to deal with the climate sometimes left us puzzled. In Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for example, where our ship had berthed for a day on its way to New York, we were stunned by the difference between the searing heat outdoors and the air-conditioned iciness inside the big stores.

Tony and I realized then that that we were just starting on the great adventure of learning how the rest of the world lives.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Scrabble and other equatorial diversions

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

After the storms and seasickness of the first week, we had perfect weather: sunny days, calm seas, and just enough breeze to keep things cool. I decided that ocean voyages were not so bad after all.

I had time to dream. When my husband Tony and I carried our bags up the gangplank of the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” earlier that month, bound for New York and then England, I felt I was walking in the steps of my role model, the great New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield, who also went abroad at a young age to pursue a literary career.

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

The Sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out;

At one stride comes the dark

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

I haven’t played Scrabble in years, and don’t remember what happened to our old game set. But this week we bought ourselves a new one. Nostalgia filled my heart as I pulled out from the bag a handful of little wooden tiles.

JVO photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet, which contains 55 years of letters, notes and memorabilia.

Hurricane at Sea

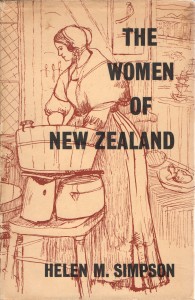

We skirted a hurricane (known as a cyclone in the South Pacific) for the first several days after my husband Tony and I left Wellington, New Zealand, bound for New York on the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt.” For most of that time I lay on my bunk, so seasick I wished I were dead just to get the misery over with. In a letter to parents I scrawled: “Mountainous heaps of water piling up all over the place, wind changing direction all day …Steady old JVO bobbing around like a cork. Thank goodness I have got my sea legs at last – after the first few days of utter misery in a very stuffy cabin. Am still on a largely dry bread and water diet – lost a terrific lot of weight. But have been reading Women of New Zealand today and decided that my lot is not too bad after all. What those women had to put up with on their voyage out to NZ makes me feel rather ashamed of myself.”

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The Ship “Kenilworth” Outward Bound for New Zealand. An illustration in Helen M. Simpson’s The Women of New Zealand, it is a reproduction of a painting by J.C. Richmond, now in the possession of the National Art Gallery, Wellington.

An early chapter describes conditions on board the emigrant ships for the four- to six-month journey from the British Isles to New Zealand. Simpson comments: “Cramped quarters ashore are difficult enough to deal with; at sea, when with every lurch of the ship ‘all things animate and inanimate’ were hurled about, children and chairs in terrifying and noisy confusion …”

Our quarters on the JVO were certainly cramped. Our lower-deck cabin had two bunks and a tiny washbasin in a space so narrow we had to take turns getting dressed. Outside in the corridor, the airless heat was rank with smells from the nearby galley. But unlike those early emigrants, we didn’t have to cook for ourselves, or bring along our own cabin furnishings.

I think of my own ancestors who braved the outward journey. A hundred years before Tony and I walked up the JVO’s gangplank, my newly-married great-great grandparents, Bernard and Sarah Donnelly, set out from County Leitrim in Ireland to join hundreds of other Irish immigrants on the New Zealand goldfields. My paternal grandfather, Charles Dinsdale, emigrated from Yorkshire, England in the early 1900s. By then steam had replaced sail, but he would have set out for his new life half-way across the world with the same sense of adventure.

In her book, Simpson tells of a shipboard fire, when passengers & crew took to the lifeboats. A woman passenger wrote that, when told of the fire, ‘I folded up my knitting, put on my bonnet and shawl, and went up.’ Simpson comments: “So figuratively hundreds of other women folded up their knitting, and, putting on bonnets and shawls, quietly faced these and other perils, and all the acute discomforts of the long voyage to the new land where their hopes rested. Dangers and discomforts were accepted without fuss.”

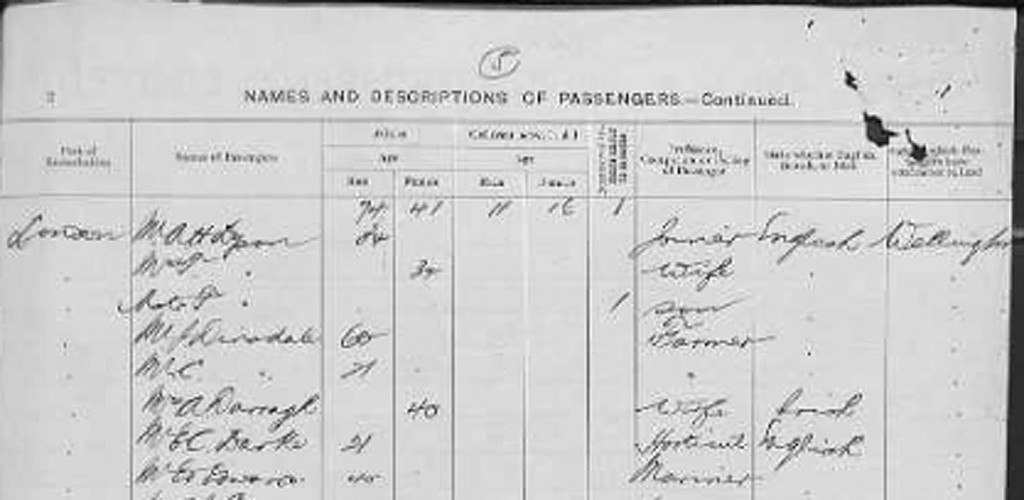

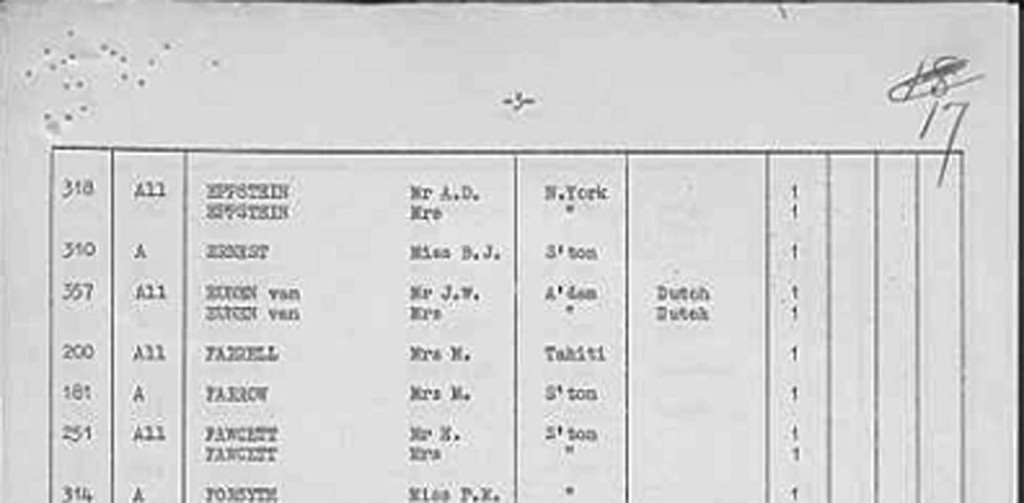

Passenger list for the SS “Corinthic” 1904. The 21-year-old C. Dinsdale (fifth name down) is probably my grandfather. From https://familysearch.org

Simpson’s standard of appropriate behavior is typical of the New Zealand society I grew up in, where we were expected to just deal with whatever hardships came our way. This is why I felt so chagrined for feeling sorry for myself.

Passenger list for the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” 1962. Our names are at the top of the page. From https://familysearch.org

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The End of a Great White Ship

The memoirist Judith Barrington and I have a ship in common. Her memoir Lifesaving has at its center the cruise ship “Lakonia,” which departed Southampton on December 19, 1963, on a Christmas voyage to the Canary Islands. Three days later, a fire broke out. In the ensuing confusion and panic, a small group of passengers, including Judith’s parents, were left stranded without lifeboats and drowned.  Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

On February 13, 1962, the previous year, my husband Tony and I left New Zealand on that same ship. At the time her name was the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt,” of Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN), also known as the Netherland Line. It was not quite her last round-the-world voyage under this flag; the maritime historian Reuben Goossens notes that her final departure from Wellington, NZ was in January 1963.

“What was it like on board?” Judith asked me. “I know my parents were on a cruise ship, but I can’t get a picture in my head of those staterooms or of being on that deck.”

I told her as best I could of the richly carved dark wood paneling that decorated the staircases and staterooms. Reuben Goossens notes that the décor was the work of famed Dutch artist Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945) and sculptor Lambertus Zijl (1866-1947). Lion Cachet “took a great delight in using some of the most exotic timbers and then mixing them with a range of materials, from marble, polished shell to tin and other unique materials. Décor throughout the ship reflected the colonial links between the Netherlands with the Far East.” Lambertus Zijl created many fine sculptures and reliefs that were to be found throughout the ship.

Cover of a JVO dinner menu. We collected and framed several of these, each showing a different bird.

Tony and I also had the sense of being on a ship with a long history. The JVO, as we lovingly called her, was launched in 1929, and was one of the most luxurious ships to be placed on the international trade route to the Dutch East Indies. She was requisitioned as a troop ship during world War II. After the war, she brought large numbers of British and Dutch immigrants to New Zealand under a government-sponsored program that provided free or assisted passages.

Refitted as a one-class cruise ship in the late 1950s, the JVO offered round-the-world and trans-Tasman cruises. Competition from airlines was by then reducing the demand for ships as a standard mode of passenger transport across seas, though airfares were still way beyond the means of most young New Zealanders. We obtained a lower level berth on the JVO for about $160 each. According to a 1963 Pan Am schedule an airline ticket from Auckland to London would have cost about $900.

So the JVO was sold in March 1963 to the Greek Line, and renamed the “Lakonia.” The cruise on which Judith Barrington’s parents perished was her maiden voyage under her new flag.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Tooth Fairy Tests for Strontium-90

While he was completing his degree, my husband Tony worked as a physicist at New Zealand’s National Radiation Laboratory in Christchurch. One of his tasks was testing for the presence of the radioactive isotope Strontium-90 in children’s milk teeth This 1960 photograph shows him working in the lab.

Since the end of World War II in 1945, the United States, along with its allies France and Britain, used the Pacific region north of New Zealand as a testing ground for nuclear weapons. By the mid-1950s, casual attitudes about fallout from these tests had given way to concern. In 1957 the New Zealand Government charged its Department of Health with monitoring environmental radioactive contamination in New Zealand and the Pacific areas with which New Zealand was associated. Since the National Radiation Laboratory in Christchurch was already monitoring radioactive pollution and controlling the safe use of ionizing radiation in medicine, education, research and industry, it seemed a logical extension to extend its responsibilities to collecting samples, analyzing and interpreting data on environmental levels of radioactivity.

The idea of using of children’s milk teeth most likely came from the Baby Tooth Survey. This project was started in the US by the Greater St. Louis Citizens’ Committee for Nuclear Information, in conjunction with Saint Louis University and the Washington University School of Dental Medicine, and inspired similar initiatives in other parts of the world.

Strontium-90, which is chemically similar to calcium, is absorbed from water and dairy products into bones and teeth, and has been linked to bone cancer and leukemia.

In New Zealand, evidence from the National Radiation Laboratory’s monitoring efforts helped moved the country toward opposition to French nuclear tests at Mururoa and to American warships’ visits to New Zealand.

In New Zealand, evidence from the National Radiation Laboratory’s monitoring efforts helped moved the country toward opposition to French nuclear tests at Mururoa and to American warships’ visits to New Zealand.

—–

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.