Archive for the ‘New Zealand’ Category

Rumblings in the socialist paradise

I sold this early 1970s article about feminism in New Zealand to a US magazine. Unfortunately, the journal folded just after I’d received the galley proofs. Disappointing, but hey, these things happen. Reading the galleys again, I recognize many of my own frustrations, and understand a little better why I had to leave. I realize, of course, that New Zealand society today is very different from what it was then.

Letter From New Zealand

In New Zealand we say it is the land that shapes the people.

The land is lovely, but aloof; it has not welcomed intruders. For a few square miles the forest and scrub have given way, but the houses sit impermanent as boxes on the clearings, and in the towns the raw suburbs perch in self-conscious rows.

Europeans have been here for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain they brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. Together these two strands wove a welfare state that, in providing an economic floor beneath which no family can fall, has codified the disparities between the sexes, and underlined the definition of woman as housewife.

In the 1930s and ‘40s the pattern of social experiment these pioneers began reached its flowering in a social security system that offered a minimum wage, compulsory arbitration of wage disputes, pensions for invalids and deserted wives, family allowances that can be capitalized into housing down payments, low interest housing loans, low rent state houses, and a national health service that provides free medicines and medical treatment. A school dental service provides free dental care for all children. Most recently, in April 1974, an accident compensation scheme went into effect that covers everyone on New Zealand soil, whether earning money or not.

It is a complacently comfortable floor. But at its foundation is the assumption that the only proper place for a woman is in the home taking care of the children.

The welfare of the child is the prevailing argument. Says Norman King, New Zealand Minister of Social Welfare: “The majority feel that a close relationship with its own mother is the birthright of the New Zealand child. We do not want to encourage the adoption of a lifestyle in New Zealand where it becomes normal for the care of very young children to be a specialist task carried out by trained staff in group situations away from the family.”

New Zealand women achieved the right to vote in 1893, second only to Wyoming. Otago University in N.Z. admitted women to degree courses in 1871, the first in the British Empire. There are today very few women Members of Parliament, and no women at all in the administrative levels of higher education. Those who have reached positions of authority in any field are regarded as exceptions to the norm. And in a country as small as New Zealand, to be different is to be disapproved. A friend who returned home after ten years in London says: “Everything in New Zealand presses on me to settle down, to conform, to live safely, not to take risks.” My elder sister, Evelyn Stokes, has a doctorate in geography from an American university. Hostile vibrations still echo in our family over her decision to place her two children in a day care nursery so she could continue her university teaching.

Official thinking assumes that a mother who goes out to work does so either from economic necessity or from disproportionate greed. The idea that women might have talents other than domestic comes hard to New Zealanders. It is certainly not fostered by our education system, which from the start locks children into rigid sex role definitions.

From six-year-old Donald, Evelyn Stokes’s son, comes a crumpled school paper.

Check what toys girls like, he is instructed.

Big and little dolls? Yes, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A train? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

A football? No, marks Donald. Correct, marks the teacher.

At the high school level the curriculum encourages vocational discrimination by sex: academic girls are steered towards the arts rather than the sciences, and average girls towards secretarial or home-craft courses.

But the winds of rebellion, fanned by global news services and travelers’ tales, are stirring the curtains at the kitchen windows. Women are staying at school longer and leaving with higher educational qualifications than ten years ago. The percentages of women and of married women in the work force are still lower than most western countries. But their numbers are increasing steadily, despite recent changes in the family benefit structure aimed at dissuading mothers from going out to work. Equal pay recently became law, and will be at least nominally applicable to all areas of the workforce by 1978.

Social custom compounds the problems of those married women who do go out to work.

Pat Brown has her own advertising agency. She told me that a company party with her husband, chief chemist at a freezing works, she attempted to discuss with his colleagues the implications of advertising and the sale of meat. Her husband’s boss took her firmly by the hand and led her to the far side of the room, where the other wives were discussing babies and knitting patterns. “This is your place,” he said.

Domestic duties are another stumbling block. Marriage counselor Marianne Thorpe says: “The difficulty is that women feel that they are responsible for the care of the home and children (and they get almost no help in this task), and this makes working outside the home a complicated business.” Evelyn Stokes and her husband Brian, head of math at a teachers’ college, share responsibility for housework and child care. It is an unusual set-up for a New Zealand family. More typical is Ray Lealand, now retired after a double career of clerical work and home-making, who says: “The most difficult problem I faced whilst working was non-cooperation from my husband.”

Role demarcation in some families is incredibly rigid. One friend recalls the raised eyebrows in her family when as a young bride she took on the vegetable garden. “That’s the husband’s job,” she was told. “The wife does the flowers.”

Since most women expect to stay home once they have a child, the idea of maternity leave is not widely accepted. When Evelyn Stokes applied for leave for the birth of her second child, the committee set up to look into the matter came back with a regulation that a mother who applies for maternity leave “is required to satisfy the university that her additional family duties are compatible with the continuation of her employment.”

Child care facilities for working mothers are inadequate, and though support for day care centers was a major plank in the ruling Labour Party’s 1972 election platform, its implementation has been whittled down to a subsidy to needy children in existing voluntary centers. Part-time employment coinciding with school hours is widely accepted, but employers will take on mothers of preschoolers only as a last resort, and use the argument of family responsibilities to pin women to the lower scale, “temporary” job classifications.

Sex role definitions still apply in employment. Six occupation groups employ 65% of New Zealand’s working women: clerical, sales, clothing manufacture, teaching, nursing, and domestic service. But there has been some movement into the traditionally male areas of drafting, electronics, and electrical work, and into the newer technological jobs like computer programming or systems analysis, where sex-exclusive traditions have not yet calcified. With a shortage of male labor in many fields, a few pioneers are braving the public ridicule and breaking down job opportunity barriers. One such incident, in 1972, even rated media coverage. Two girls applied for jobs in an Auckland factory as aluminum glaziers, only to be told this was not a woman’s job. When they asked “Why not?’ no answer could be found, and they were taken on.

This thread of social change is closely woven with another that is a constant in New Zealand life. Few in numbers, and isolated by thousands of miles from the sources of our culture, we have been almost pathologically dependent on the word from the outside world. I remember my first beat as a cub reporter; I scurried round the tourist hotels of Christchurch, winkling out startled visitors and begging them to express an opinion. Any opinion. Still the pattern continues. Articulate voices from abroad, no matter what their status, receive far more attention than local expects on the same subject.

The feminist movement is a case in point. Local groups springing up in the past few years have found a climate of hostility and ridicule. The ideas of American feminists, distorted by distance and by different cultural norms, have seemed to many to be irrelevant to the New Zealand experience. Then early in 1973 two visitors coincided: Evelyn Reed, an American Marxist feminist who advocated abortion law reform and improved child care facilities, and Dr. John Bowlby, a British psychiatrist know for his work on the deleterious effects of maternal deprivation on a child’s mental health. Both, basking in the aura of the magic words “from overseas,” were taken seriously by the local press. Margot Roth, editor of the Journal of the N.Z. Society for Research on Women, comments that the resulting controversy opened up a much wider range than usual of questions concerning women, and helped lay the foundation for the success of a United Women’s Convention held September 1973 in Auckland to mark the 80th anniversary of women’s suffrage.

The purpose of the convention, according to the organizers, was to correct the distorted view New Zealand women had of modern feminism, to raise the status and self-confidence of women, and to increase the numbers of women willing to work on behalf of women’s issues.

Statistics indicate that the fifteen hundred women who attended, while better educated and more likely to be employed than the average, nevertheless made up a remarkably accurate cross-section of New Zealand society. The issues discussed were those that concern women everywhere: job opportunities, control of their bodies, marriage and child care, sex stereotyping.

Press reportage of the Convention again sought to trivialize and ridicule. Afternoon TV revealed to local mums some of the hogwash poured down the verbal ducts at the United Women’s Convention, reported one city daily.

However, rage over press flippancy reinforced a feeling of unity at the conference, and the consensus of those who attended is that, for the first time, women from the whole range of backgrounds and interests in New Zealand life experienced a feeling of sisterhood.

The floodgates are open. Women with common interests are pooling resources. The prestigious National Council of Women, umbrella for all women’s organizations in New Zealand, and for long a stronghold of the traditional view, is now espousing the cause of equality and encouraging its affiliated groups to contribute.

It is hard to say what the future will hold. Though New Zealanders travel the world as casually as migrating godwits, jet planes cannot eliminate the sense of lonely isolation that makes us belittle our homegrown prophets. The land still broods, raw, stubborn, and the people it has bred still revere the sheep shearer above the artist. On embroidered tablecloths, housewives still set teas of cream cakes and scones, and rows of preserves still gleam on pantry shelves.

But the women of New Zealand have a stubborn streak too. Diffident, shy, self-conscious in proclaiming the ideas that come from an almost alien American culture, we are nevertheless gathering strength. The spirit that made New Zealand one of the most comfortable societies in the world may yet take a mattock to the scrublands of tradition, and graze the new fields of equality.

Fight or flight: an expatriate ponders

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

In this period of political unease in the US, when many have expressed a wish to go live somewhere else, I think back to our last few years in England in the mid-1960s, and how alienated we felt then.

An economics text for UK students cites several reasons for the dour mood of the country in those years. Author Tejvan Pettinger writes:

Despite higher economic growth, the UK performed relatively poorly compared to major competitors. UK productivity growth was relatively lower due to several factors. such as:

- Lack of willingness / ability to innovate

- Poor industrial relations with a growing number of days lost to strike action. Some argue this was exacerbated by Britain’s class system.

- Trade unions effectively blocked efforts at reform.

- Complacency.

- Lack of public sector infrastructure.

Even though we might have returned to New Zealand then, our lives did not take that turn. In my old black filing cabinet I found a letter to my parents that lays out the situation.

19 July 1966

… [W]e are still unsettled about what we are going to do with ourselves. We did have serious ideas of returning to New Zealand, but I am afraid that is now dropped through lack of interest on the part of N.Z. firms. We are feeling rather sour about the whole affair, especially as N.Z. is always griping about the country’s young brains staying away in their thousands. A year ago Tony made a private enquiry to I.C.T. (NZ) asking about the prospects of getting a job, and did not even get the courtesy of a reply. Then six months ago head office in London offered to arrange a transfer for him. After much prodding, official letters to N.Z. eventually got answered, but in such unsatisfactory terms that no-one knew quite what they wanted. It has taken six months for N.Z. to agree to take Tony, but they have made it plain that they consider he is being foisted on them by London, and that they are still suspicious of him. Their terms are that he is to have a year’s training in computer systems, and not until “they see how he gets on with the training” will they consider discussing position or salary. Since Tony is one of I.C.T.’s top authorities on computer tape, and already has a big general background in computer systems, he has taken this as a not-so-polite brush-off and told them what they can do with the job. If he were in his early twenties, without family, and determined to get back, it might have been different. But at his age—rising thirty is a critical age in his line of industry, since the job decisions he takes now will set the line his career is to take. So you see he just can’t afford to throw away yet another year on a job that might still not eventuate, and would probably be a frustrating backwater if it does. Other computer firms in N.Z. take much the same line—not interested enough to get him an interview in London, just “drop in when you get to N.Z. and we will see if there is anything doing.”

Meanwhile, he is still negotiating for a job with an American firm, which might mean going to live in California, but nothing has been settled yet, We feel it is time we got out of this country—the present economic crisis is just a symptom of a general decadence and backward-looking attitude, and we can’t see any future for Britain.

You mentioned your feelings towards Britain as a spiritual home—I can understand this, and think it is one of the main forces that pushes young people into coming over here. I think it is this thing about historical roots—it gives a wonderful sense of history and continuity to visit places that have been lived in for so long by so many different peoples. But it is necessary to distinguish between this feeling and the present political reality. Modern Britain doesn’t care two hoots about New Zealand—it is either confused with Australia (well, they are both on the other side of the world, what does it matter?) or else N.Z. is regarded as some sort of idealised paradise where it is never rainy or cold, and where they would like to go to escape from reality. As a political or economic entity it just doesn’t exist. And while N.Z.ers continue to believe that it doesn’t exist either, except as an offshoot of Britain, there is not much hope for its future, and the young brains will continue to stay away in their thousands.

Which makes us more or less permanent exiles, at least spiritually. But if we do go to America, it is probable that Tony will be earning enough money for us to afford the occasional holiday in N.Z. I feel very sad that the children do not yet know their grandparents, but that is one of the penalties of our decision. I hope you will understand.

Oh, to be shoe-less in the summer sun

My sister Alison’s family, gathered in New Zealand for Christmas. It’s summer there, that time of year. Note the absence of shoes.

My old black filing cabinet has yielded a treasure: the carbon copy of a 1960s letter to a newspaper editor. Reading it again, I’m struck by how much it reveals about my homesickness for the more casual lifestyle of New Zealand and my resentment of the strictures of English custom. I was reminded of these differences when my sister Alison, who lives on a beach north of Auckland, posted on Facebook a photo of her gathered family, and American friends of the family joked about the lack of shoes. Here’s the 1964 letter:

The Women’s Editor

The Guardian

Manchester

Dear Madam,

As a fellow colonial I share [Guardian feature writer] Geoffrey Moorhouse’s feelings about English clothing habits. The conformity begins at an early age. This summer my one-year-old toddler and I have been subjected to cold stares and even sarcastic comments from total strangers. The cause is his shoe-less feet. I am obviously considered a poor mother, for not providing leather for his feet, and looking round, I noticed that even during the hottest days, while my infant sat comfortable in only napkin and sunhat, most of his contemporaries were firmly laced into heavy shoes, and many were even inflicted with neatly buttoned shirt and tie.

I am not against shoes on principle. Now that the weather is turning cold, my son wears shoes and socks with his long trousers. But I do object to this pressure to dress young children according to society’s idea of respectability, disregarding the dictates of the weather.

I don’t go barefoot in Mendocino. It’s cold here, and there’s burr clover and native blackberry underfoot. But sometimes I miss those carefree New Zealand summers of my youth.

My first cuckoo

Sumer is icumen in

Lhude sing cuccu

Listen to this Medieval rote song

An English oak woodland. Image from Open University on the BBC

My first spring in England, late afternoon in Windsor Great Park. Green-gold light through ancient oaks, the air rich with leaf-mold and violets. A cuckoo calls. I have heard the sound all my life, in music and poems, but never before in the wild.

Listen to the cuckoo calling in this recording from the British Library

As I stand listening, this spring in 1962, something shifts in my thinking. It is as if previously I saw the world through two mesh screens, one named Southern Hemisphere and the other Northern Hemisphere, half a year out of alignment with each other, so that my view was blurred by the moiré patterns their meshes made. The religious festivals my ancestors brought from the northern hemisphere when they emigrated to New Zealand lost their old association with the seasonal cycles of life and death when celebrated in the reversed seasons of the southern hemisphere. In consequence, I felt, even as a child, a subtle sense of having been cut off at the roots, of being, even after several generations, transplanted British.

Images float into my mind. Mid-morning, Christmas Eve, at All Saints Church in Tauranga, NZ. Strewn mounds of flowers deck the chancel steps. The Altar Guild ladies are filling shiny brass vases that stand either side of a red-draped altar. Bronze-purple foliage of copper beech, fans of gladiolus spikes, the tropical exuberance of canna. They add dahlias, roses, bougainvillea until the reds vibrate.

Sunlight through stained glass glitters on the sharp points of holly springs that I strew along the dark wood windowsills, hiding jam jars filled with red geranium flowers. The holly bears no berry here, this time of year, and the carol I hum under my breath echoes in an empty place inside me. Later, at midnight services, the congregation sings of light in darkness and the falling of snow. We emerge to warm air, misty moonlight, and the scent of magnolias. This Christmas is not real, I think to myself. It’s pious make-believe.

Easter: after morning church and family lunch, I gather with siblings and cousins on the porch to smash the Easter eggs we have all been given. Molded of hard sugar, they are pastel pretty, with piped-on decorations of flowers and leaves, the symbols of spring. Having gorged ourselves, we scamper off to scuffle through autumnal leaves.

Cuckoo image from

Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

My reading in college, particularly J.G. Frazer’s The Golden Bough, helped me recognize that Christian festivals have pagan roots: the ritual victim dies at planting time; the winter birth is the rebirth of the sun. As the cuckoo calls again, cu-coo, over and over, quietly, the blurred meshes of my hemispheres resolve and I see through: myself and my people bound by tangled apron strings to the life our forbears left, and to the earth itself, an old reality, almost forgotten.

What I learned at Stanford

The New Zealand high school I went to, Tauranga College, recently celebrated its 70th anniversary and hosted a reunion for those who attended the college before 1957, the year it split into two single-sex schools. I was one of four alums invited to give a five-minute talk on some aspect of our lives. I was in prestigious company: an emeritus professor of chemistry, the manager of New Zealand’s cricket team during many of its World Series tours, and a researcher doing impressive work in health economics. I chose to talk about my 20 years as an administrative writer and editor at Stanford University, a relatively low-level job, but one in which I had considerable personal satisfaction.

Later that day, many women came up to me to tell me how much they appreciated my words. “I felt affirmed,” one woman said. Our generation was taught rather firmly that a woman’s role in life was to marry and take care of husband and children. Many of course took on paying jobs and volunteer work, but “women’s work” was not highly valued in that strongly patriarchal society.

Here’s the text of my talk:

What I learned at Stanford

I’m sure most of you have heard of Stanford University. The name might bring to mind words like Silicon Valley, medical breakthroughs, prestigious think tank. There’s another, less visible part of the story: the staff work that keeps the university going.

I’m still amazed at how I found myself there in 1979. I was easing back into the job market after being a home-maker and struggling freelance writer. At a neighborhood gathering, I learned that the Stanford administration had a crisis. The federal government was changing the rules for how to calculate the indirect costs for research contracts and grants. (For instance, how much of the university’s electricity cost can reasonably be charged against a particular contract.) When the finance department and the research department put together task forces to figure out how to implement the new rules, they discovered that the faculty doing the research had no idea what the accountants were talking about. They needed someone to translate accounting-ese into English. Could I do it? my neighbor, a Stanford professor, asked. At that time my accounting knowledge was zilch. But what I did have, as a journalist, was the ability to ask the dumb questions that would get me a highly technical story in everyday language. So I was taken on, and within a couple of weeks was ghost-writing memos for the Controller and the Dean of Research.

I stayed at Stanford for twenty years, working on projects related to administrative systems and policies, and support networks for department administrators. During that time, Stanford administration was going through a sometimes painful transition to the world of computers. Imagine if you will a dark basement in an old stone building. Rows of desks are filled with elderly women, most of whom have been there forever, processing Accounts Payable by hand. They’ve never touched a computer, and they’re terrified.

I was part of a group doing our best to help ease this transition. For instance, when I became editor of Stanford’s annual financial report, the entire $450 million of income and expenditures was typed up and tallied by hand. I brought in someone familiar with a computer spreadsheet program to reduce the manual labor. As editor of administrative policies, I headed up an Information Technology skunk works to fulfill a dream of making all the university’s policy and procedure documentation available online. (This was in the early 1990s, before the World Wide Web took off.) I also designed and implemented support programs to gently persuade computer-phobic department administrators to give up their paper copies and use the new system. These programs were the topic of papers that I presented at national conferences.

Sometimes I would ask myself: Does anyone really understand how much power I have? How is it that I, a relatively low level administrative analyst and editor, am dictating annual report deadlines to Stanford’s prestigious external auditors, or leaning on vice-presidents to update their policies, or even writing the policies for them?

The answer is that there are two kinds of power. One is hierarchical: you’re the boss, so you have the right to tell those under you what to do. The other kind of power is interpersonal: if people trust and respect you, they will willingly help you implement a common goal. I learned at Stanford that trust and respect are really all that matter.

A taonga returns home

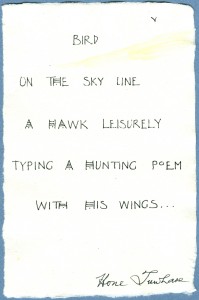

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

This week, when I fly to New Zealand on a family visit, I will have with me a small sheet of drawing paper. In a top corner is a drawing of a bird flying over a hill, with a delicate watercolor wash. The rest of the sheet contains a tiny poem, hand-written in beautiful calligraphy, and signed by the poet/artist, Hone Tuwhare.

The manuscript is one my treasured possessions. I have pangs of regret about parting with it, but know I am doing the right thing. In New Zealand Tuwhare’s work is considered a taonga, a treasure. He was the first M?ori poet writing in English to win widespread acclaim. His best-known book, “No Ordinary Sun.” first published in 1964, was reprinted ten times over the next thirty years, becoming one of the most widely read individual collections of poetry in New Zealand history. The title poem is a response to French nuclear testing in the Pacific. Many more collections followed. His work has a conversational tone and incorporates both M?ori and biblical rhythms; the subjects range from the political to the personal and often powerfully evoke the beauties of nature. He won several New Zealand book awards, and was poet laureate of New Zealand in 1999–2000. He died in 2008, at the age of 85.

The M?ori concept of taonga also includes the story that goes along with the item. My little manuscript was a gift from Jean McCormack Tuwhare, Hone’s ex-wife. She and my mother-in-law were friends. On a visit to New Zealand in 2000, I spent a delightful afternoon with Jean at Mother’s house discussing poetry and literature. Mother had shown Jean my first poetry collection, “A Place Called Home,” and later suggested I send her a copy. Enclosed in Jean’s thank-you letter for the book was the Tuwhare manuscript. Unfortunately the letter is lost, but as I recall, Jean wrote that Hone (with whom she was still close friends) liked to practice calligraphy and had given her several of these small pieces to dispose of as she wished. She thought I might appreciate having one.

[Update 6/2/1016: While in New Zealand, I learned from Rob Tuwhare, Hone and Jean’s son, that Jean herself did the calligraphy, and Hone signed her work.]

I am of an age when I need to make decisions about my stuff. Knowing that the manuscript could easily get overlooked among our mountains of paper and art works, I sought professional help. I told Malcolm Moncrief-Spittle of Renaissance Books (New Zealand) , who deals in rare and out-of-print books, that I thought my taonga should be returned to New Zealand. Which university or cultural institution in New Zealand already houses a collection of Tuwhare material and would be a suitable recipient? I asked. He recommended the Hocken Library at the University of Otago in Dunedin.

Staff at the Hocken Library responded to my query with enthusiasm. We’ve arranged a meeting on May 9, when I will hand over the carefully packaged manuscript. I know it will be a happy/sad occasion.

Airline pilot: a loyal expat

Among the New Zealanders Abroad series I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper in the 1960s is a lengthy interview with airline pilot Captain Ronald Hartley. His celebrity in 1962 was as commander of the airliner taking Princess Margaret and the Earl of Snowdon to Jamaica for the independence celebrations. Later that decade he flew Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh to Canada.

Princess Margaret dancing with Sir Alexander Bustamente at the Jamaican Independence Day celebrations. From http://blogs.jamaicans.com/

A World War II Royal Air Force hero, Hartley helped form an airline that amalgamated with B.O.A.C. He was one of the first B.O.A.C. pilots to train on Britannia aircraft, and in 1962 was deputy flight manager of the Britannia 102 flight. Much of his work involved the planning of new aircraft, such as the Vickers VC10.

“We are surrounded by experts who know what is possible – it is our job to stand in the middle of the argument and tell them exactly what we require.” In such things as the layout of cockpits pilots can bring practical experience, and Captain Hartley and his colleagues are at present working for a standardization of cockpit design. This is so that a pilot can if necessary step into a strange place and know where all the instruments are likely to be on the panel.

Captain Hartley was born in Auckland in 1909. When he was 19 years old his parents returned to England, taking him with them. Although he never returned to New Zealand, Captain Hartley was still very proud of being a New Zealander.

“There is something about the land of one’s birth that makes you always loyal to her,” he said. He is proud of New Zealand’s social legislation, and the high reputation that New Zealanders have in England, a reputation gained, he thinks, from their service during the two world wars.

His memory of New Zealand is a picture of beaches and bush. “When I was a boy we used to jolt down a dirt road to the beach at Muriwai or Piha, and when we got there we would have the whole place to ourselves – not like the noisy, overcrowded holiday places here in England.” He remembers Boy Scout camps on the shores of Manakau Harbour, with the bush coming down to the water, and long hot summers with warm water for swimming. Now he has a cottage in Devon, but even in mid-summer the water could only be described as “bracing.”

He found the different way of life in England hard to get used to at first. “In my first year I rushed around joining clubs – tennis clubs, athletics clubs, anything to make friends.” He was conscious of the class distinctions in English society. ”It sometimes worried me that I didn’t know much about things like wines, or the right brand of cigars or caviar. Now that I am older, and know more about me, I have learned better.”

He had come to realize that most people needed his help and friendship more than he needed theirs, and he has worked on this assumption throughout his career.

“I have tried to bring up my children the same way too. When they showed signs of shyness at an early age, I used to tell them, if they were going to a party: “Now don’t you dare have a good time until you see some little boy or girl who looks lonely and make friends with him.”

For the new immigrant to England such as myself, his comments about not being able to return permanently to his birthplace were an uncomfortable revelation, and one we quickly discovered for ourselves. He was having too much fun, he said.

“I enjoy dealing with people, and I love the clash of personalities and opinions that you get in such a huge and complex organization as this.”

Postscript: on Nov. 21, 1969, Captain Hartley was killed when as a passenger on a Nigerian Airlines flight, the new Vickers VC10 crashed on its landing approach to Lagos airport.

Translucent angels

The glass artist John Hutton was on the list of New Zealanders living abroad that my editor at the Christchurch, NZ Press handed me when I left the paper in 1962. “He’s been working for years on a project for the new Coventry Cathedral. Go check out how it’s going,” he said.

Also known as St. Michaels, the original cathedral in Coventry, England was constructed between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. It was gutted by incendiary bombs during World War II; only the tower, spire, the outer wall and the bronze effigy and tomb of its first bishop survived. After the war, a decision was made to build a new cathedral and to preserve the ruins as a constant reminder of conflict, the need for reconciliation, and the enduring search for peace. The architect, Sir Basil Spence, proposed that the new cathedral should be built alongside the ruins, the two buildings together effectively forming one church.

Spence commissioned many magnificent art works for the new modernist building. Hutton’s contribution was to be a great glass screen for the west end of the new cathedral.

This image of Hutton’s great glass screen was posted by ashleyniblock on http://www.vortis.com/blog/

Unfortunately, the text of my interview is lost, but I still have a letter I wrote about our visit to Hutton’s studio near London:

May 9, 1962

One of the vases made by Hutton for sale at Coventry Cathedral. It is decorated with figures which appear among the images in the Great West Screen. It is now in the University of Warwick Art Collection.

Another artistic experience of a quite different sort was on Monday – we went out to interview John Hutton, a New Zealand artist who has made the great glass screen for Coventry Cathedral, which is to be consecrated this month. The panels are engraved with saints and angels, in a very bold scribbly style that nevertheless has a rich Gothic quality about it. We were very impressed, and also with his other work that he has at his studio – more glass work, but also paintings, and many other media as well. Just wish we had a hundred pounds to spare – he is making a series of vases, each engraved with two of the angels, which the cathedral is selling to raise funds.

Revisiting this story feels particularly relevant today. From the window of my office at the Christchurch Press, I used to look out at ChristChurch Cathedral, which was destroyed in the earthquake of 2011. Arguments are still going on about whether to rebuild or replace a building that was the physical and spiritual center of the city.

Hurricane at Sea

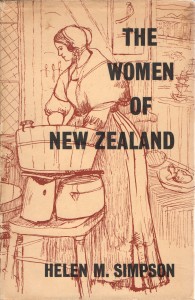

We skirted a hurricane (known as a cyclone in the South Pacific) for the first several days after my husband Tony and I left Wellington, New Zealand, bound for New York on the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt.” For most of that time I lay on my bunk, so seasick I wished I were dead just to get the misery over with. In a letter to parents I scrawled: “Mountainous heaps of water piling up all over the place, wind changing direction all day …Steady old JVO bobbing around like a cork. Thank goodness I have got my sea legs at last – after the first few days of utter misery in a very stuffy cabin. Am still on a largely dry bread and water diet – lost a terrific lot of weight. But have been reading Women of New Zealand today and decided that my lot is not too bad after all. What those women had to put up with on their voyage out to NZ makes me feel rather ashamed of myself.”

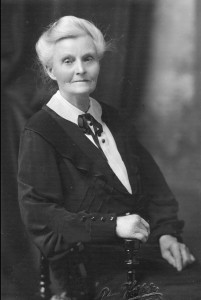

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The book I referred to, The Women of New Zealand by Helen M. Simpson, had been a parting gift from my parents, who had come to Wellington to see us off. First published in 1940, it was a vivid description of the lives of pioneer women.

The Ship “Kenilworth” Outward Bound for New Zealand. An illustration in Helen M. Simpson’s The Women of New Zealand, it is a reproduction of a painting by J.C. Richmond, now in the possession of the National Art Gallery, Wellington.

An early chapter describes conditions on board the emigrant ships for the four- to six-month journey from the British Isles to New Zealand. Simpson comments: “Cramped quarters ashore are difficult enough to deal with; at sea, when with every lurch of the ship ‘all things animate and inanimate’ were hurled about, children and chairs in terrifying and noisy confusion …”

Our quarters on the JVO were certainly cramped. Our lower-deck cabin had two bunks and a tiny washbasin in a space so narrow we had to take turns getting dressed. Outside in the corridor, the airless heat was rank with smells from the nearby galley. But unlike those early emigrants, we didn’t have to cook for ourselves, or bring along our own cabin furnishings.

I think of my own ancestors who braved the outward journey. A hundred years before Tony and I walked up the JVO’s gangplank, my newly-married great-great grandparents, Bernard and Sarah Donnelly, set out from County Leitrim in Ireland to join hundreds of other Irish immigrants on the New Zealand goldfields. My paternal grandfather, Charles Dinsdale, emigrated from Yorkshire, England in the early 1900s. By then steam had replaced sail, but he would have set out for his new life half-way across the world with the same sense of adventure.

In her book, Simpson tells of a shipboard fire, when passengers & crew took to the lifeboats. A woman passenger wrote that, when told of the fire, ‘I folded up my knitting, put on my bonnet and shawl, and went up.’ Simpson comments: “So figuratively hundreds of other women folded up their knitting, and, putting on bonnets and shawls, quietly faced these and other perils, and all the acute discomforts of the long voyage to the new land where their hopes rested. Dangers and discomforts were accepted without fuss.”

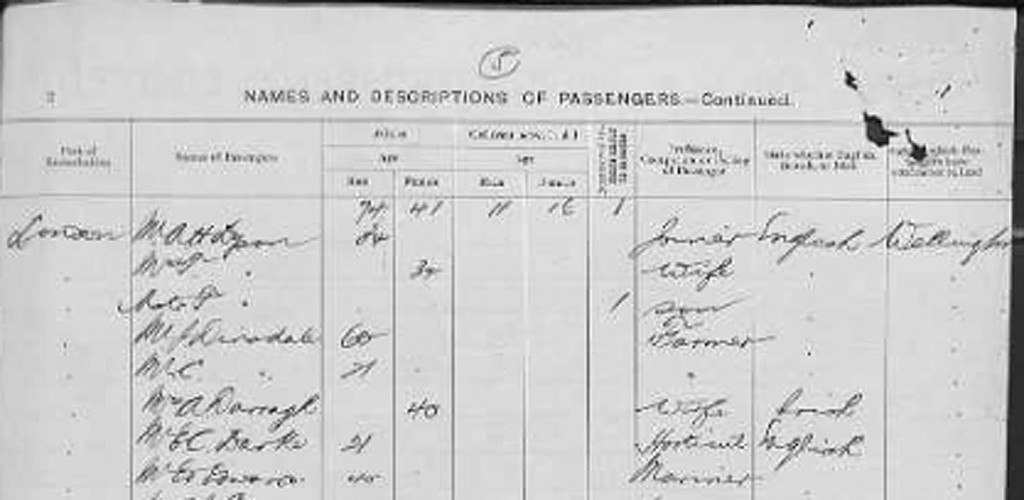

Passenger list for the SS “Corinthic” 1904. The 21-year-old C. Dinsdale (fifth name down) is probably my grandfather. From https://familysearch.org

Simpson’s standard of appropriate behavior is typical of the New Zealand society I grew up in, where we were expected to just deal with whatever hardships came our way. This is why I felt so chagrined for feeling sorry for myself.

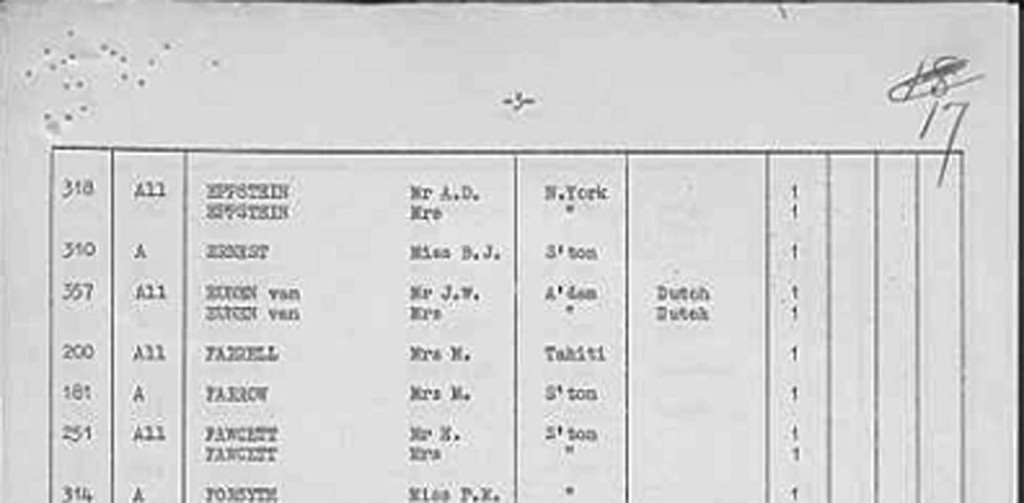

Passenger list for the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” 1962. Our names are at the top of the page. From https://familysearch.org

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The End of a Great White Ship

The memoirist Judith Barrington and I have a ship in common. Her memoir Lifesaving has at its center the cruise ship “Lakonia,” which departed Southampton on December 19, 1963, on a Christmas voyage to the Canary Islands. Three days later, a fire broke out. In the ensuing confusion and panic, a small group of passengers, including Judith’s parents, were left stranded without lifeboats and drowned.  Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

Lifesaving is the story of a young woman struggling to become an adult in the shadow of this loss.

On February 13, 1962, the previous year, my husband Tony and I left New Zealand on that same ship. At the time her name was the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt,” of Stoomvaart Maatschappij Nederland (SMN), also known as the Netherland Line. It was not quite her last round-the-world voyage under this flag; the maritime historian Reuben Goossens notes that her final departure from Wellington, NZ was in January 1963.

“What was it like on board?” Judith asked me. “I know my parents were on a cruise ship, but I can’t get a picture in my head of those staterooms or of being on that deck.”

I told her as best I could of the richly carved dark wood paneling that decorated the staircases and staterooms. Reuben Goossens notes that the décor was the work of famed Dutch artist Carel Adolph Lion Cachet (1864-1945) and sculptor Lambertus Zijl (1866-1947). Lion Cachet “took a great delight in using some of the most exotic timbers and then mixing them with a range of materials, from marble, polished shell to tin and other unique materials. Décor throughout the ship reflected the colonial links between the Netherlands with the Far East.” Lambertus Zijl created many fine sculptures and reliefs that were to be found throughout the ship.

Cover of a JVO dinner menu. We collected and framed several of these, each showing a different bird.

Tony and I also had the sense of being on a ship with a long history. The JVO, as we lovingly called her, was launched in 1929, and was one of the most luxurious ships to be placed on the international trade route to the Dutch East Indies. She was requisitioned as a troop ship during world War II. After the war, she brought large numbers of British and Dutch immigrants to New Zealand under a government-sponsored program that provided free or assisted passages.

Refitted as a one-class cruise ship in the late 1950s, the JVO offered round-the-world and trans-Tasman cruises. Competition from airlines was by then reducing the demand for ships as a standard mode of passenger transport across seas, though airfares were still way beyond the means of most young New Zealanders. We obtained a lower level berth on the JVO for about $160 each. According to a 1963 Pan Am schedule an airline ticket from Auckland to London would have cost about $900.

So the JVO was sold in March 1963 to the Greek Line, and renamed the “Lakonia.” The cruise on which Judith Barrington’s parents perished was her maiden voyage under her new flag.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.