Archive for February, 2015

Inside a 1960s newspaper office

In graduate seminar at the University of Canterbury, Professor Neville Phillips fixed me with a stern eye as he returned my latest effort. “You are getting through your history papers, Miss Dinsdale, on your writing style, not on your knowledge of history.” I flinched, and worried. Graduation was coming up, and I planned to apply for a job on The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. Within the next week or two I needed to ask him for a letter of reference. Not only was Prof. Phillips head of the history department, he was a former newspaperman himself, and still had deep connections at The Press.

I needn’t have worried. Not only did he write me a nice reference, he also penned a personal note to the paper’s editor, Arthur Rolleston (Rollie) Cant, that opened the door to my dream job.

Press Building, Cathedral Square, Christchurch, NZ. Photo by Michael Whitehead from

http://www.nzine.co.nz/features/150years_the_press.html

I had known since childhood that writing was what I wanted to do. Movies about newspapers such as While the City Sleeps (1958), Deadline – U.S.A. (1952) and Ace in the Hole (1951) filled me with fantasies about the drama and excitement of the reporter’s life. Here was my chance to prove myself.

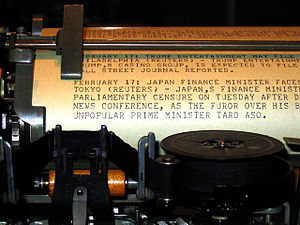

I loved working at The Press. A great Gothic pile on Cathedral Square, in the heart of Christchurch, the Press Building was a newspaper office out of one of those Hollywood movies: a cavernous newsroom that smelled of newsprint and dust, where telephones jangled, the chief reporter barked commands and the urgent clatter of the Teletype machine signaled a breaking story somewhere in the world.

Picture of Merganthaler linotype machines in a compositing room from the archives of the Nieman Foundation http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/

Sometimes I would be sent on an errand out back to the compositing room, a shadowy cave where enormous Mergenthaler Linotype machines made a deafening clatter. Deeper into the heart of the building, the throb and rumble of the great press itself, and the bustle of loading trucks in the small hours of the morning for long distance runs. When The Press celebrated its 100th anniversary in May 1961, its circulation was 62,000, with subscribers throughout the South Island.

It felt glamorous to work late into the evening, rushing back from meetings to meet the deadline for next morning’s paper. I shared dreams with the other young reporters, all of us with a few scratched notes tucked away for what each of us was sure would be the Great New Zealand Novel. We all had the sense of being part of an old tradition.

Among my notes I found this description of the office, written in 1960. Christchurch at that time was a sleepy provincial city of 193,000 people, and exciting news stories didn’t happen all that often.

I described the office as a jumbly assortment of rooms, all dirty and uncared for, and with space saving nonexistent.

I particularly appreciated my desk in the women’s department, by a window where I could gaze out across Cathedral Square. I’ve written about this view in an earlier post.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Alas, the old Press Building is no more, a victim of the February 22, 2011 Christchurch earthquake, four years ago today. The staff now report the news from a new modern building nearby.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Cooking for 120 in a remote fishing camp

The Curious Cove camp, now known as Kiwi Ranch. It looks much the same as when I worked there in the late 1950s.

If you take the ferry from Wellington, New Zealand across Cook Strait and through the Marlborough Sounds to Picton, at the northern end of South Island, you will sail past the entrance to Curious Cove. At the tip of that narrow inlet is the tiny fishing camp where I worked through all my college vacations. Reachable only by boat, Curious Cove was a magical little world. The job, passed down through word of mouth by University of Canterbury women students, was perfect for this impoverished student, with board and lodging provided, nothing but a tiny tuck shop to spend money in, and a nice paycheck at the end of the season. I started off as a kitchen hand and was later promoted to second cook.

The guests, about 120 at a time, would come in for a couple of weeks. We would feed them a full breakfast, then scramble to pack lunch sandwiches for those going out fishing. Those who stayed behind got freshly baked scones with their mid-morning tea, and a salad and cold cuts lunch. By late afternoon, when the launch, “Rongo” hove into view with Charlie the skipper at the helm, the kitchen crew was already at work on the evening meal. It would be plain, traditional New Zealand fare: a roast with gravy and several vegetables, plus a dessert such as apple shortcake with custard.

Here’s a classic New Zealand apple shortcake recipe.

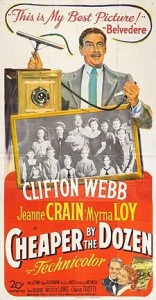

Almost everything was made from scratch. The 1950 movie Cheaper by the Dozen, the story of time and motion study experts Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and their twelve children, was as big a hit in New Zealand as it was in the U.S. Following the Gilbreths’ methods, the Curious Cove kitchen crew, being university students, amused ourselves by figuring out more efficient ways to do things.

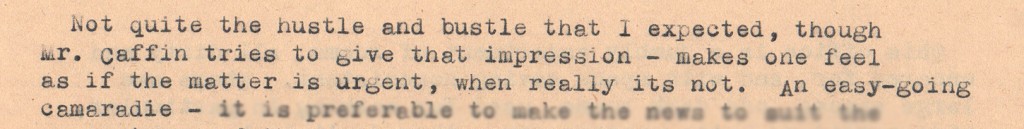

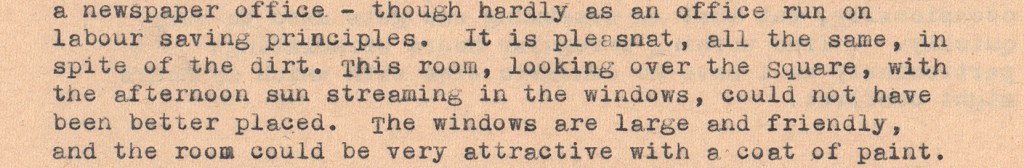

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

I wrote this little column in 1960 or ’61 as a filler for the women’s page of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

How I scooped the sports department

Chat with famous race car driver’s mother

Bruce McLaren in the 1969 German Grand Prix. Photo by Lothar Spurzem, via Wikimedia Commons

Getting the interview was easy. The mother of race car driver (and later designer) Bruce McLaren was my Great-Aunt Ruth, whom had known since I was a kid.

In January 1961 my cousin Bruce was back in New Zealand after an impressive debut on the Formula One circuit, where he had joined his mentor Jack Brabham on the Cooper racing team. In December of 1959, at the age of 22, he had become the youngest-ever winner of a Formula One race, capturing the U.S. Grand Prix at Sebring. He became a star overnight.

Here is a Pathé newsreel clip from that race.

The following year, Bruce came in second only to Brabham in the standings for the Formula One World Championship. Understandably, all New Zealand was agog.

Knowing via family that Auntie Ruth and Uncle Les planned to be in town to act as staff for Bruce as he worked the New Zealand racing circuit, I arranged to visit them at their hotel. Perched on the bed with our cups of tea, my aunt and I settled in for a cosy chat. Auntie Ruth was a great raconteur, and since I already knew the family history, it took little prompting on my part for her to re-tell her best stories.

The interview ran much longer than usual, but the editors at The Press published it in full. The day it was published, almost all the men from the sports department and the general reporting pool stopped by the women’s department to congratulate me. “How on earth did you get that interview?” the sports editor asked. I just smiled.

Bruce went on to establish Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Ltd. Unfortunately, in June 1970, he was killed while testing a McLaren CanAm car at his company’s site in England. His company lived on and today enjoys the reputation as one of the world’s foremost racing teams. Bruce was inducted into the International Motorsports Hall Of Fame in 1991.

I’ve appended a transcription of the interview with Great-Aunt Ruth.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

The Press, Saturday Jan 21, 1961

Car Racing Dominates McLaren Household

Car parts on the kitchen table, race tracks round the backyard, nothing but gear ratios and car performances for conversation and sleepless nights waiting for results from Europe have been the lot of Mrs Ruth McLaren, the mother of the racing driver Bruce McLaren, ever since her marriage more than 30 years ago.

“But I wouldn’t have missed a bit of it,” she said in Christchurch yesterday.

Even before her marriage, Mrs McLaren knew she would have a life in which racing played a big part. It was motor-cycles then. Her husband, Mr Les McLaren, and his two brothers were all motor-cycle racing enthusiasts – and highly successful ones.

In 1936 a dislocated should made Mr Les McLaren give up motor-cycles. Two or three years later he became interested in racing cars.

World War II ended all racing, but after the war Mr McLaren did a great deal of club work in hepolite trials and hill climbs.

Bruce, aged eight at the time, was interested even then, and two years year, when he entered Wilson Home with a hip disease, he insisted on regular reports from his father.

Muddy Clothes

After Bruce came out of the home, at the age of 12, he spent 12 months with a hip sling and crutches. Football was out, much to his disappointment, but Mrs McLaren still found her share of muddy clothes to wash when Bruce and his father went on hill climbs and mud trials.

Bruce’s first car was an Austin seven, which he acquired and “hotted up” at the age of 14. That was the end of Mrs McLaren’s garden. Too young for his driver’s licence, Bruce could not drive it on the roads, so he made a race track round the backyard and through the orchard. “No garden, and no branches left on the trees, either,” Mrs McLaren recalled.

Every visitor to their Remuera home was initiated to the track, and had to endure a hair-raising and head-ducking ride round the course.

From driving-licence age on there was a series of gymkhanas, hill climbs and mud trials, Mrs McLaren said. “It was a great thrill seeing him win—we used to go everywhere with him.”

Parts in Kitchen

When Bruce was 16 his father acquired an Austin Healey, which had something special about its engine. Although Mrs McLaren has picked up a great deal of motoring jargon, she cannot remember exactly what it was. All she remembers is the gloating and loving care with which the parts in question were polished on her kitchen table, and the piles of engine parts on the back porch, which she dared not disturb.

Many motoring friends would drop in, and the men would sit for hours discussing the finer points of their machines. “I would just sit there, getting their food for them when it was a meal time—but I don’t think they even noticed what they were eating,” said Mrs McLaren.

By this time both Bruce and his father were driving the Austin Healey. There came a day when the son drove it faster than the father. that was the day when the father decided it was about time he quit.

Waiting for News

The news that Bruce had won the driver-to-Europe award caused great excitement in the McLaren household. Later, when he had gone, came the terrific strain of waiting for results.

“I just lived on my nerves the week-ends he was racing,” said Mrs McLaren. Always at the back of her mind was the fear of a crash. “We have great faith in Bruce’s driving ability, but there are always things beyond his control. But he has not had an accident yet—touch wood.”

The McLarens waited anxiously for the first B.B.C. news in the morning, since the results of the championship races were always announced, and the news would come faster than a cable.

Visit to Europe

Two seasons ago, Mr and Mrs McLaren went to Europe and followed Bruce around the championship circuit. “We had a wonderful time—the racing fraternity accepted us as one of themselves, and looked after us wonderfully,” said Mrs McLaren.

During the races in New Zealand Mrs McLaren acts as lap scorer, but this was Mr McLaren’s job on the European tour. Mrs McLaren’s job was to stand by with wet towels and warm pullovers.

With the wives of drivers and team managers, she would go shopping and sightseeing in the towns of Europe. “Usually someone in the party would speak the language, which helped a lot,” she said.

Language difficulties often caused panics on the racing circuits. “The turns of phrase were often confusing in the commentaries, and often we could only pick out the names. Once we heard ‘McLaren, wheel of Cooper’—we had visions of all sorts of accidents, but they only meant that he was driving the Cooper,” she said.

Brabham’s Crash

When Jack Brabham crashed in Portugal, Mrs McLaren was with his wife Betty in the pits. “It was dreadful—it was only half-way through the race, and we had to wait till the end of the 72 laps to get across the track to find out whether he was all right.”

And the end they dashed across the track, jumped into Bruce’s car and to the hospital, where they found after much difficulty and confusion that Brabham was not hurt, but was being kept under observation.

On another occasion in France, when the temperature was 96 degrees in the shade, and 136 degrees on the race track, Bruce came into the pits after the race badly cut with flying stones.

Now Mr and Mrs McLaren wait through the year for the few crowded weeks when Bruce is home. “It makes up for all the time he is away,” said Mrs McLaren. The house is always full of drivers and friends, and is besieged by young autograph hunters.

“It’s very hectic, but very exciting. I wouldn’t miss it for anything,” said Mrs McLaren of her life as mother of a racing car driver.

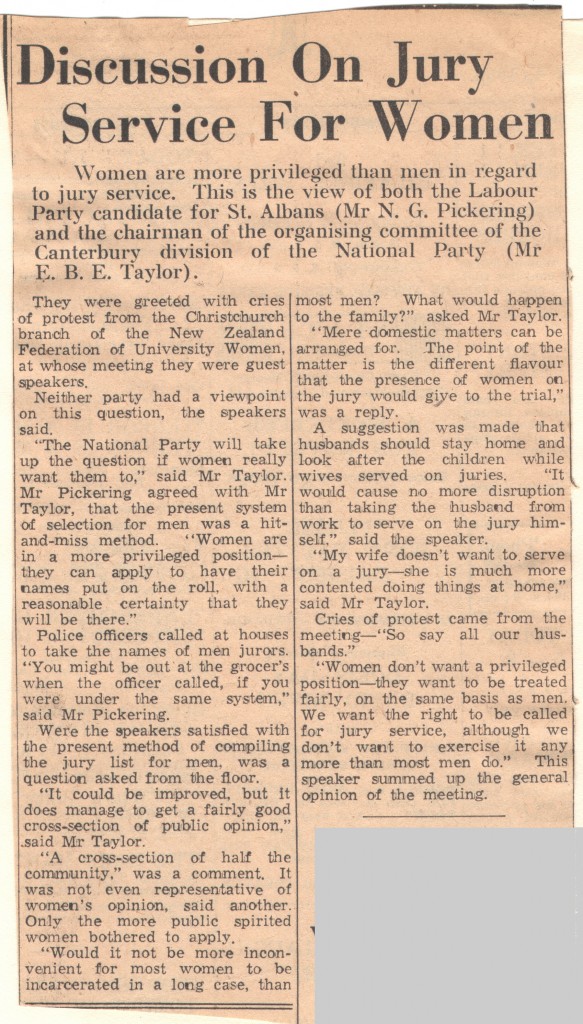

Jury Service for Women

We were a subversive bunch in the Women’s Dept. of The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper, even though the editorial stance of The Press was socially and politically conservative. In the early 1960s a big issue for women was the right to serve on juries on an equal basis with men. Until 1942, New Zealand women were denied the right to sit on juries, and even after that date, they had to apply to have their names put on the rolls. Only the most civic-minded women, referred to in some quarters as battleaxes and stickybeaks, volunteered to do so. The official view was that compulsory jury service might interfere seriously with the home-making responsibilities of women.

I remember the glee with which I returned to the office from a meeting of the Christchurch branch of the New Zealand Federation of University Women and regaled my colleagues with the drubbing the guest speakers, two male politicians, received concerning this attitude.

I followed up with a survey: Was there a “strong and clearly expressed” desire by Christchurch women for this equality of status? I’m probably guilty of compromising the survey’s objectivity by giving prominent coverage in my report to a woman with strong egalitarian views, but am comfortable my conclusion is valid:

A petition to Parliament in 1963 resulted in a compromise: the Juries Amendment Act of 1963 made women liable to be included in the roll in the same way as men, but gave a woman an absolute right to have her name withdrawn on request. This right was cancelled in 1976. Jury service for men and women then became completely equal.

NOTE: The issue of jury service for women in the United States followed a similar trajectory, though complicated by variations among states. In 1979 (three years after New Zealand) the U.S. Supreme Court overturned automatic exemptions for women.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.