Archive for May, 2015

Cycles of life

This week’s post is reprinted from the Arts & Entertainment section of the May 29 Palo Alto Weekly. Henri and I are very excited about our upcoming reading.

Cycles of life

Two poets return to Palo Alto for shared reading

by Elizabeth Schwyzer / Palo Alto Weekly

Poets and friends Henri Bensussen, left, and Maureen Eppstein will read their work in Palo Alto on Friday, June 5, at Waverley Writers. Photo by Tony Eppstein.

“My friend’s body is a brown leaf,” writes Maureen Eppstein in “Going Dark,” a poem from her recent chapbook, “Earthward.”

” … the fierce flame of her will/refuses surrender./ It’s not death’s darkness she resists/but the loss of a self transfixed/by what is beautiful.”

That same enthrallment with life she witnesses in her dying friend is evident throughout Eppstein’s collection of 26 poems. Beguilingly simple, founded in close observations of nature, these poems unfurl to reveal the writer’s keen sensitivity, sense of humor and clear acknowledgment that every life ends with death.

On Friday, June 5, the former Palo Alto resident and Stanford University employee will return to town to read from her new collection. She’ll be joined by fellow poet Henri Bensussen, also formerly of Stanford. Both longtime attendees of Palo Alto’s hallowed Waverley Writers — a free, monthly poetry reading founded in 1981 — Eppstein and Bensussen separately retired to Mendocino County, where they’re each active in the writing community. Their Palo Alto visit marks more than 15 years since their departures — Bensussen and her partner left the region in 1999, Eppstein and her husband in 2000 — yet both are well-remembered by area poets.

Janice Dabney, who shared a writing group with Bensussen and Eppstein and worked alongside Eppstein both on the Waverley Writers Steering Committee and at Stanford, spoke of both writers as “very good people” and recalled not just Eppstein’s poetry but also her humanity.

“She was very supportive of me being a gay person,” Dabney recalled. “She made a point of putting her money where her mouth is, which is a good summary of Maureen: She’s not a person who sits idle and spouts philosophies; she gets out there and acts and makes the world a better place.”

Those on the Mendocino Coast speak in equally glowing terms about both women and their work. Norma Watkins, secretary of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference and creative-writing instructor at Mendocino College Fort Bragg campus, explained of Bensussen, “Henri was my student in the past and writes this delightfully quirky prose and poetry. She has a very odd and wonderful imagination so that when you begin reading one of her poems, you never know where it’s going to go.”

Director of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference, Karen Lewis, said of Eppstein, “You can tell from her work that she has a daily, connected presence in nature. Her nature metaphors are especially remarkable.”

Lewis also described a new project of Eppstein’s: a collection of short essays based on her youth in New Zealand and her immigration to the United Kingdom. Those essays can be found at maureen-eppstein.com.

Bensussen, too, mines her own past for material. In “Chimney Rock,” a poem from her new and first chapbook, “Earning Colors,” birds of prey serve as metaphors for partnership and a departure point for a meditation on separation and divorce:

“Peregrine falcons nest in a hollow/under the cliff’s rim. They mate/for life, unlike us or elephant seals.”

Later, she shows herself, standing alone as birds swoop overhead:

“Vultures hunt the dead, veer close/when they notice me. I stare them off. Pose — /Still Life: Woman in Love, Once.”

Both Bensussen’s “Earning Colors” and Eppstein’s “Earthward” are published by Finishing Line Press, a small publisher based in Georgetown, Kentucky. Bensussen explained that she entered the manuscript in a poetry contest with Finishing Line, and though she did not win, they offered to publish the chapbook anyway.

As for the collection’s title, “When you send in a poetry manuscript, it has to have a thread or theme,” she explained. “I realized I had quite a number of poems centered around the idea of color.”

Like Eppstein, Bensussen has a deep connection to nature, one fostered by her studies in biology and many years of birding and gardening. Upon moving to Mendocino, she explained, “I became immersed in the natural history of the area, and also fascinated by how people interact. Often, someone says something and it sends me off on a poetic journey.”

“Earning Colors” is full of evidence of such journeys. Friends’ stories and strangers’ cast-off comments pepper the collection, giving the sense of a writer moving through a crowded room, picking up on snippets of conversation. In “Blood Test,” it’s an “overly friendly” nurse whose question about the origins of Bensussen’s name sends the writer into reflections on “disruptive history,/as tubes fill with dark pulses of my life.”

Life and death draw close in both Bensussen and Eppstein’s work.

“Earthward,” Eppstein’s third poetry chapbook, is “really about the cycles of life and death,” she explained. “It’s centered around the poem ‘Going Dark,’ which was written for a friend in New Zealand as a memorial. She suffered from multiple sclerosis for 40 years, gradually losing more and more of her use of her limbs. Toward the end of her life, we would have conversations about how she was afraid of losing the self that could be moved.”

The self that can be moved is on full display throughout “Earthward,” and the scenes that move the poet are often those drawn from nature. In “Osprey with Fish,” Eppstein writes with simple power of three lives: the bird, the fish and the woman who watches their flight:

Undercarriage of leg and talon

joins two bodies similar

in sleekness,

twinned

as life and death conjoin

in a continuum

of nourishment.

Huge wings slow over forest,

a fading cry.

“Earning Colors” and “Earthward” are available at Books Inc., Town & Country Village, Palo Alto, and online at finishinglinepress.com.

What: A reading by poets Maureen Eppstein and Henri Bensussen

Where: Waverley Writers, Palo Alto Friends Meeting House, 957 Colorado Ave.

When: Friday, June 5, 7:30 p.m.

Cost: Free

Info: Go to tinyurl.com/l4lvwgh or call ![]() 650-424-9877.

650-424-9877.

The Language of Plants

Have you ever wondered whether trees talk to each other about what’s going on in the forest? Can they show compassion or motherly love? Do they team up to ward off an attack?

Recent research has shown that plants communicate using an electrochemical “language.” Taking a break from exploring my old black filing cabinet, I’d like to share a poem about this discovery. It’s from my new collection, Earthward, available from Finishing Line Press.

The Language of Plants

We who move about are at a loss.

We do not know what words to use

for speech that has no metaphor

in the human tongue.

We have ways to speak of learning,

words for memory, decision-making words.

We speak of synapses of neurons in our brains,

name the organs that receive our senses—

ears, eyes and noses, taste buds, fingertips—

words all based on human forms.

The standing-still ones

message their pheromones into the air:

Aphid invasion. Deploy toxin defenses.

Send for the predator wasp to counter-attack.

Roots zing with electrochemical charge

as through their internet—

a mycorrhizal tangle of yellow threads—

they share resources with their kin,

and even with neighbors of other ilk:

Fir borrows summer sugar from birch,

pays it back in the time of barren twigs.

We need new definitions to embrace

the beings who feed on light

not in some alien galaxy

but close at hand:

Does intelligence mean to have a brain

or problem-solve?

New ways of standing in a bean patch

or a forest grove

in awe and wild surmise at all

this human brain can not yet comprehend.

A Kiwi at the Top

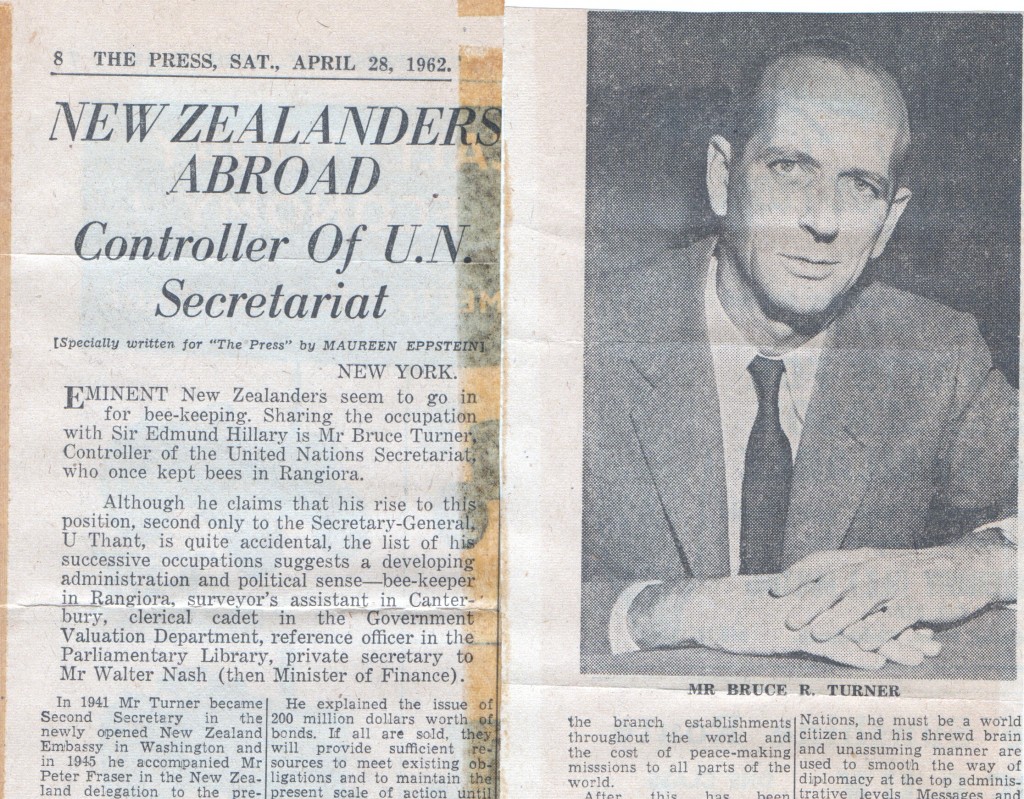

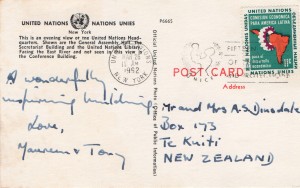

It felt like being in a fairytale. There I was, a country bumpkin on the 37th floor of the United Nations Building in New York, interviewing a man second only to Secretary-General U Thant himself.

When I left my job at The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper, to go abroad in 1962, the paper’s editor handed me a list of names. “These are New Zealanders who have done something interesting with their lives. Track them down and send me back some interviews,” he said.

On the list was Bruce Turner, Controller of the UN Secretariat. In a letter to parents, I described him as “A typical Kiwi c haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

Here’s a transcript of the interview.

1962 Bruce Turner interview

Eminent New Zealanders seem to go in for bee-keeping. Sharing the occupation with Sir Edmund Hillary is Mr Bruce Turner, Controller of the United Nations Secretariat, who once kept bees in Rangiora.

Although he claims that his rise to the position, second only to the Secretary General, U Thant, is quite accidental, the list of his successive occupations suggests a developing administrative and political sense—bee-keeper in Rangiora, surveyor’s assistant in Canterbury, clerical cadet in the Government Valuation Department, reference officer in the Parliamentary Library, private secretary to Mr Walter Nash (then Minister of Finance).

In 1941 Mr Turner became Second Secretary in the newly opened New Zealand Embassy in Washington and in 1945 he accompanied Mr Peter Fraser [the NZ Prime Minister] in the New Zealand delegation to the preparatory commission on the first session of the new United Nations.

“Here Mr Fraser had the misguided generosity to lend my services to the first Secretary-General, Trygvie Lie, and I haven’t been able to get out of it ever since,” Mr Turner said recently in New York.

Vast Responsibility

On him rests the responsibility for all financial aspects of the organisation’s activities. “And since everything we do involves money, this means, in effect, the whole lot. The position would be comparable in New Zealand to that of the Treasury, the Auditor-General and in some respects the Public Service Commission, all rolled into one. Sometimes I suspect that I don’t know entirely what the job involves myself,” he said.

His department prepares in advance a budget of regular expenditure. This includes the administration of the secretariat in New York and the branch establishments throughout the world and the cost of peace-making missions to all parts of the world.

After this has been approved by the Administration and Budgetary Committee of the General Assembly, commonly known as the Fifth Committee, the money is collected on a quota system, based on the capacity of each member government of the United Nations to pay. This quota is periodically revised by a committee of ten experts.

But for extraordinary expenditures, such as the United Nations Emergency Force sent to the Middle East in November 1956 and the force sent to the Congo in July, 1960, a separate budget is required, although the proportion borne by each country remains the same.

A Major Problem

Here lies one of Mr Turner’s biggest headaches. Certain countries claim that they have no legal liability for their quota of this extraordinary budget. Meanwhile, funds are running low, but the need for maintaining forces in the Congo continues.

He explained the issue of 200 million dollars worth of bonds. If all are sold, they will provide sufficient resources to meet existing obligations and to maintain the present scale of action until the end of 1963.

Mr Turner put the problem in the smoothly rounded language of diplomacy and press statements: “On the success of this bond issue depends the future of the whole organisation and its peace-keeping operations.” He broke off to joke grimly: “Oh well, if it fails, this place will be blown up and I will be out of a job.”

He spread his hands lightly round the pleasant wood-panelled room with its quiet beige and jade upholstery. Heavy curtains hid a view of the East River and Brooklyn in the early evening. On a low table, beside a bowl of spring flowers, a handsome Maori carving gave a hint of the occupant’s country of origin.

“Some day I might retire to New Zealand—that would be the normal procedure for any expatriate New Zealanders,” he said. “It would be somewhere with a warm, mild climate. Tauranga perhaps—that is not too far from my friend in Hamilton who owns a brewery.”

Meanwhile, like all other employees of the United Nations, he must be a world citizen and his shrewd brain and unassuming manner are used to smooth the way of diplomacy at the top administrative levels. Messages and telephone calls continued to pour into his office, telling of Government decisions on the bond issue. The maintenance of forces in the Congo, while still a grave problem, seemed a little more hopeful.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Art stuns like a hammer blow

With gold velvet drapery as backdrop, the newly acquired Rembrandt, “Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer,” stood on an easel in the foyer of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Spotlights accentuated the golden glow of the painting’s surface. As I gazed, I felt a resonance with the feelings of the person depicted, my thoughts drawn into his as if into a dizzying vortex. I was astounded that brushstrokes and pigment could have such power to move me.

I had not seen great art before, except in books of reproductions. I had devoured the collection of large format books in my high school art room, and spent hours browsing the art section of secondhand book shops when I was in college. When we left New Zealand in 1962, Tony and I had as a priority to visit art museums and see the work of artists we admired. But nothing had prepared us for being in the presence of the real thing. Upstairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art we found a whole room of Rembrandts. Dancing down a broad staircase, a whole series of bronze sculptures by Edgar Degas. We saw so many great works we discovered the phenomenon we named “mental indigestion” and wished we had more time in the city so that we could come back. We knew it would take weeks, months even, to absorb all this museum had to offer.

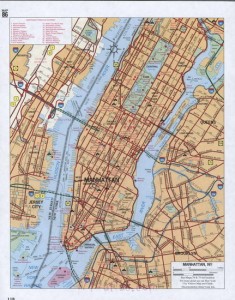

We visited other art museums during this stopover in New York on our way to England. Some we loved, some less so. In a letter to parents I wrote: “Sunday afternoon we went out to The Cloisters, which is right up at the northern tip of Manhattan. This is a religious museum. Parts of the remains of many old churches of Europe have been brought across and incorporated into the present structure, which keeps as closely as possible to the original styles. In a sense it is a success – some of the old fragments of stonework are very fine, and there are some very fine paintings, altar ornaments, and some magnificent tapestries – the highlight of the whole exhibition. But in spite of their attempts to reproduce chapels, all sense of reverence has been lost – the things are a curiousity for the locals to gawp at, and even sacrilegious.”

As I look back on these youthful letters and these memories, I see opinions about what matters to me already forming and clarifying. Many more experiences of the power of art would come in future years: sitting on a bench in a crowded London gallery, weeping over Georges Rouault’s “The Old King;” gazing in awe at the rose window in Chartres Cathedral; feeling the silence of the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Always, enriching these experiences, the memory of that stunning awakening in New York.

Country bumpkins in New York

The friends we were traveling with chose the hotel, the cheapest they could find. It was on W. 46th Street, just off Times Square. Only one thin hand towel in the grungy bathroom. What to do? We called the desk. A maid appeared, to tell us the towels were not yet back from the laundry. In hindsight, a tip might have made towels magically appear. But we knew nothing about tipping; it wasn’t a part of the culture we knew.

Breaking our 1962 journey from New Zealand to England as young married couple off to see the world, Tony and I had disembarked in New York to visit my sister Evelyn, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University in upstate New York. From there the three of us traveled by Greyhound bus to Baltimore to spend a few days with her friends Brian and Jennifer Wybourne and visit Washington, DC.

Driving with the Wybournes back to New York, where we were to board another ship bound for England, we were wide-eyed at our first glimpse of the New Jersey turnpike. In a letter to parents I wrote: “…one of the most famous of the turnpikes – 150 miles of unhindered 6-lane highway. Then navigating the streets of the city – practically all are one-way, which makes it complicated, and you can imagine the traffic.”

The letter continues: “The next morning we went up to the top of the Empire State building – early, before the mist got up. The view from the top is terrific – you can see the whole extent of New York city – which is saying something.” I look back in memory and see the young woman I was, neck stiff from craning upward at rows of skyscrapers that made deep canyons of the streets, mind agog at the level of luxury displayed in store windows. I remember wandering through several of the huge department stores, feeling lost and out of place.

One day we walked to the tip of Manhattan and back, excited to see Wall St. and Greenwich Village, and to walk on Broadway. I wrote: “We were really footsore by the time we reached the hotel, but then we had the big experience of our trip – riding the New York subway during rush hour. That was some experience. We held each other tightly, and shoved with the rest. Sardines in a can had nothing on the train – but you had to make sure you weren’t pulled out with the rush at each station.” Evelyn, who was taking us out to the Bronx to dinner with the family she was staying with, wrote in her letter home: “I deliberately engineered it to be at Grand Central Station about 5 past 5 at night. It was quite an eye-opener for them…”

On each of the other nights we had the new experience of dining in a restaurant of a different nationality, all quite cheap by New York standards, and all in the same block as the hotel – Greek, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, as well as American – hamburgers and doughnuts.

For lunch Evelyn introduced us to automats. I commented: “We found foreign food much more interesting than American – they process it and vitaminise it, and goodness knows what – the result is rather tasteless.”

In future weeks I’ll talk about other aspect of our first visit to New York: the art, the music, the experience of visiting the heart of the United Nations secretariat.

And yes, a few more threadbare towels did eventually show up in our hotel room.