Archive for June, 2015

Westernesse in the rain

An Aran Island scene on a sunnier day. This aerial photograph by Aongus O’ Flaherty is from http://www.aerarannislands.ie

My first glimpse of the British Isles was the Aran Islands, at the mouth of Galway Bay, where our trans-Atlantic ship stood off to land a few passengers. It was an emotional moment. The destination of our long sea journey at last become visible. Vague romantic dreams faced with reality. I was shocked by the bareness and bleakness of the landscape. Heavy rain was falling, and wind lashed waves onto the shore. The bare rock of the grayish white hills (karst limestone, I later learned) was dotted with tiny scraps of green that glowed brightly in the rain-sodden air. A few white cottages of plain design: four walls and a pitched roof, a door in the middle and small windows at each side.

In notes written at the time, I tried to capture my sense of the place:

Centuries old, yet timeless. Feeling of age and solidity of a way of life that has gone on for centuries – the grimness of it, the few rewards. Can imagine the people to be tough and dour. Weather-beaten faces of seamen who brought the tender out to pick up passengers. No-nonsense faces, with a wry sense of humour.

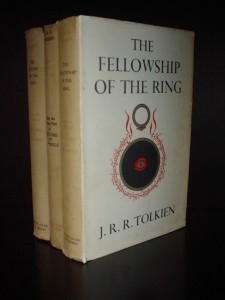

The Lord of the Rings trilogy in its original format as published by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. in the mid-1950s.

From halfway across the world, the reality of the British Isles was also mixed with romantic fantasy. Before we left New Zealand, copies of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, with the device on its cover of Sauron’s eye within the Ring, surrounded by Elvish script, were passing from hand to hand among our friends. As I looked across the sea to this westernmost part of Ireland, I couldn’t help thinking of Tolkien’s Westernesse, the place to which the fairy people set out when life on Middle Earth became impossible for them.

The curtain of rain swept down again. The ship moved on, headed for Southampton, the end of our journey and the beginning of our new life.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Doomed romance on the high seas

Observing one’s fellow passengers is a major pastime on board a ship crossing the Atlantic, especially for someone with dreams of making her name as a writer. Among the yellowing notes in my old black filing cabinet I found a brief sketch of a man who shared our dining table when Tony and I crossed from New York to Southampton in April 1962.

Gerry was a young American playwright off to Dublin to try his luck on the Irish stage. He told us he lived in a shack on Santa Monica beach, where his wife supported him while he wrote plays. The plays had been performed by amateur groups, but not professionally. He has left the wife in the shack on the beach with her dog for company, while he tries find work in Dublin – anything to do with theatre – stage hand, etc. I wrote:

Tall, lean, dark-haired, glasses, rather dreamy abstracted look, well-cut clothes. Gives the impression that his plays are about the grave problems of the world, though he never spoke of their content. Did not appear to be very interested in the people around him – hardly noticed most of them – except a blonde who had engaged the deck chair next to his. Tall, well-built girl, clear-cut features, thick mane of soft fair hair piled seemingly carelessly on top of her head. Poise and assurance. Swiss. Appeared to laugh at his moonstruck attitudes. He came when she commanded to the bar with her, and sat until far into the night. But on the last night, she refused to come to the empty chair at our table to join him in coffee and liqueurs – pleaded another engagement. So he had a liqueur brought to her at her table. Conspicuous mark of favour, as no-one else at that table was drinking liqueurs. Gerry utterly miserable until he left the ship – followed her with his eyes like a dog, and spent as much time as possible with her. She tolerated this, but obviously not as heart-broken as he.

My writer instincts set me to imagining the wife and creating motivations for Gerry and the blonde woman:

Can infer probably wife G. left at home was too devoted, believing too much in his great abilities. Probably small and neat, shiny dark hair, possibly cut short, light blue eyes. Quite happy to provide material needs so that he can have peace to get on with his writing. Likes to discuss his plays with him as he writes, but believes everything he does is so good that she is unable to provide stimulus by disagreeing with him.

By contrast, the blonde doesn’t give a damn about him, is contemptuous of his writing ability, but still allows him to flatter his ego a little by accepting attentions from him. G. confused in his own mind. Talks a great deal about his wife – not about what she is like, but her abilities at cooking, etc. – providing him with comfort, pampering him, giving him the security that a child needs, and that he is now missing. At the same time tormented by the physical attractiveness of the blonde, and by her superiority to him, not only assumed by her, but actually so: she is more sure of her place in the world. He finds her indifference to his art stimulating and at the same time humiliating; he believes very seriously in his art, but as yet has nothing to prove it to himself or others – no success as a practical yardstick. Believes he can see new horizons of human experience opening for him in the duality of his relationship to her, excited by the effect this will have on his art, though as yet it does not occur to him how he will put this into words, and is more attracted to her because of this.

Most of his actions a form of posing, related to his belief in himself as an artist, e.g., self-conscious staying up drinking far into the night, arriving half an hour late for meals, with the obvious inference that he has been too lost in his art to notice the time, or else too busy drinking his life away at the bar – those around are expected to take the explanation that appears to them the most romantic.

I don’t know how the rest of Gerry’s life turned out. Googling his name turned up no clues. All that remains is this little story of a doomed shipboard romance and a young man with a dream.

Music of the Elysian Fields

Growing up in New Zealand, the Metropolitan Opera House in New York was the stuff of dreams: the tragic drama of the opera plots, the names of the great stars, the LP disks in my mother’s collection played over and over. To actually be there was an extraordinary sensation. “The whole place just breathes atmosphere,” I wrote to my parents, “the opulent decorations of a former era, and the shades of the singers who rose to fame on its stage – portraits of the greatest everywhere. “

Thursday, March 29, 1962 was our last night in New York before my husband Tony and I took ship for England to continue our youthful adventures. My sister Evelyn treated us to the opera tickets as a grand finale to our visit with her. The performance that evening was Gluck’s “Orfeo ed Euridice,” a very quiet, 18th century version of the story, with a happy ending. To quote from the Metropolitan Opera synopsis:

“Overcome with grief and remorse, the poet cries that life has no meaning for him without Euridice (“Che farò senza Euridice?”). Preparing to take his own life, he resolves to join his wife in death. Before he can do so Amor appears and announces that Orfeo has passed the tests of faith and constancy and restores Euridice to life. The happy couple returns to the upper world, where they are greeted by friends, who perform dances of celebration. Orfeo, Amor and Euridice praise the power of love.”

What stays in my memory is the dancing. As I wrote to my parents: “The ballets, particularly in the scene in the Elysian Fields, are really beautiful. I think it is the ballets that really make the opera – the terrific contrast between this scene and the previous one – the Furies at the entrance to Hades – all dressed in torn black tights, writhing and twisting, outlined against eerie red flames.”

Here is a YouTube recording of Gluck’s Elysian Fields ballet music.

If you’d like to learn more about the performers, here is a page from Opera News, March 10, 1962

I also found this March 1962 review by Irving Kolodin in the Saturday Review:

“On the whole, the visual aspects of this ‘Orfeo’ were more absorbing than the aural, for Harry Homer’s settings (of 1938) still provide an atmospheric frame for the action and Violette Verdy (a replacement for the absent Alicia Markova) is an excellent dancer, as is Arthur Mitchell, who shared the place of prominence with her. John Taras designed the choreography, which was theatrically justifying if somewhat showy, in its lifts and leaps, for the repose of the Elysian Fields.”

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes