Archive for July, 2015

Navigating the spider web

When Tony and I finally arrived in London after our weeks-long journey, our college friends Bill Moore and Robert Ludbrook met us at Waterloo Station. I felt like hugging them both, but thought they might be embarrassed, I wrote in my notes. New Zealand men of our time did not go in for overt displays of emotion.

An early 20th century view of Waterloo Station. It looked much the same in 1962. Image from http://www.heritage-explorer.co.uk/

Robert spoke of his and his wife Miriam’s “traumatic experience” when they arrived. They sat for three hours in the huge Waterloo station, not knowing whether they were on the right platform, not sure what to do, or even if they could get to Derby, in the middle of the country, where Miriam’s parents lived. Their ten-month-old baby was crying from hunger – none of them had eaten for three hours. They knew no-one in the city. “I decided then that no-one I called my friend should suffer the same fate,” Robert said.

Waterloo Station is part of a transportation network that on a map looks like a giant spider web with the heart of London at its center.

The trains link to London’s famous Underground system, with which I became very familiar in the next few weeks as I searched for short-term accommodation while Tony job-hunted. I found these notes in my black filing cabinet:

Several days [after our arrival] I returned to Waterloo, and could not remember ever having seen the concourse of the station before, yet we must have passed through it on our way to the underground platform. I can remember the way the train came into the main platform – rows of long platforms jutting out into the track, with the entrance at the head of them, and the high wrought iron and glass ceiling, very dirty, overhead.

And I can remember standing on the underground platform, although that memory rapidly becomes confused with standing on other underground platforms, all confusingly similar. Always the same smell, compounded of dust and disinfectant and human bodies, always the same roar of the escalators, the same draughts of air rushing in or out, and the airless feeling when a train has passed, the rattle and screech of the trains grating on the ear-drum and jangling the nerves. The hypnotic movement, grinding to a halt at stations, and the doors swishing open. Some go in and some go out, but they are always the same people.

It is very easy to miss your own station if you do not concentrate very hard. The signs are easy to follow – in the station itself you do not get lost unless you are very blasé and think you know where you are going – but all the stations appear exactly the same – it is just that in each the maze of tunnels is different. But once on the right train you feel that you are safe, that you can relax for a while from the struggle of finding your way about. This is the most dangerous of all, as before you know what has happened, the train will have swished past your station while you were still dreaming.

Stereotypes and misconceptions

When I lived in England in the 1960s it bugged me that, when they learned where I was from, people would typically have one of three responses:

1) They had no idea where New Zealand was.

2) They thought it was part of Australia.

3) They knew of it as that pastoral paradise they’d dreamed of emigrating to when they were younger.

Reading my old notes about coming to England in 1962, I realize that I too had huge misconceptions about what my new home would be like. Here is the account of our arrival:

First view of England – not counting faint views through the foggy channel – picturesque houses of Isle of Wight – only we thought it was Southampton and decided England must be charmingly antique and folksy, with church spires peeping through the trees and glowing green fields running down to the sea. but we were a little perturbed that we couldn’t get our geography right. Fascinated by the light – very soft, still a little hazy after the rain and fog of the day before, but with the sun coming through in pale golden streaks.

Our ship anchored off the Isle of Wight and passengers were sent ashore by tender. We managed to miss the boat train by being held up at Customs – a fuss over a lens Tony had bought in New York. But were well looked after by the railway porters, who rushed to get us into a taxi to catch the same train at the central station. On the way, the taxi-driver casually pointed out the old Roman wall of the town. As we gazed in amazement at something 2000 years old, and taken for granted, we began to realize the sense of history about the place, which confirmed even more the feeling of newness about New Zealand. My notes continue:

As the train pulled out of the centre of Southampton we discovered the slums. Obviously not the worst of the slums, but up till then we haven’t really believed that they existed, although we could mention them matter-of-factly. England from New Zealand looked a golden land, a land of opportunities, a land that housed the rich heritage of the old world. It definitely did not mean rows and rows of dreary brick buildings exactly alike, and behind them rows and rows of exactly similar yards, with blackened paling fences and rubbish tins. But occasionally we recognised the cry of a human spirit – from among the debris would rise a patch of golden daffodils dancing in the pale sun, cultivated by loving hands. And for a time we passed through farmland, with pussy-willow growing fat by the railway track, and small boys ambling cheerfully by hedges. Even one or two thatched cottages and barns, and we felt with a sentimental rush that we really were in England. But as we neared London the houses grew thicker and more dreary, their bricks blackened with smoke and soot, their monotony more grey. But even here people were making the best of their situation with window boxes full of bright flowers.

As well as misconceptions, I had opinions. I was amused to find in my notes that, with no knowledge of English social attitudes and no background whatsoever in urban planning, I laid out an argument about high density housing:

I have not yet resolved the problem of what is the best form of high density housing for such a city. Most people are housed in these old row houses, a monotonous block, but at least with some little bit of ground, however filthy and untidy, that they can call their own. The other alternative seems to be tall apartment blocks in their own parks. The disadvantage of these seems to be that the people shifted into them lose their sense of community – they no longer feel that their home is their castle, for they share it and its services with dozens of other families. I would feel the lack of a bit of ground of my own to cultivate, or just sit in. A semi-public park is all very well, but it gives no opportunity for creative contact with the earth. I have seen a few modern blocks of row houses, some of which are quite pleasant, but others will obviously become the future counterparts of the present monstrosities – pleasing to look at now because they are new, but once the newness has worn off little of artistic value will remain. Others, particularly a small block seen near Primrose Hill, had a cheerful friendly atmosphere that appeared more durable.

Ah, the certitude of youth.

The Rain in Spain and all that

In April 1962, fresh off the boat from New Zealand, I stood on a railway platform in Southampton, on England’s south coast. All around me the sound of voices, English voices. In notes written a few days later, and saved in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

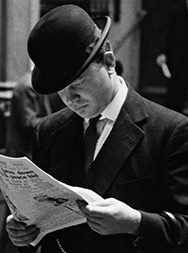

Railway platform – probably much the same as those in NZ, but had a sense of Englishness about it – hard to define, but probably due to the language spoken – correct English accents as if they were the most normal thing – this takes a bit of getting used to. … Here on the Southampton platform we heard the ‘jolly hockey sticks’ manner of speech for the first time. In all cases, it is difficult to distinguish in the mind between the real thing and the caricature which up to now is all we have known. The same with men in bowler hats and umbrellas.

Reading these notes fifty-three years later, I see in them the ambivalences and ambiguities that filled my formative years. Europeans had been in New Zealand for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain, the English, Irish and Scots immigrants brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. For my father and his friends, a man was considered useless unless he was good at working with his hands. An Englishman, especially if he had a “posh” accent, was teased about being a “Pom” and eyed with suspicion until he could prove himself as one of the blokes.

On the other hand, well-spoken Englishwomen dominated the social life of the resort town where I grew up. English bone china teacups clinked in parlors where pictures of thatched cottages might grace the walls, and genteel conversation was made about making the trip “Home” to the old country.

Prejudices about accent can cut both ways. The longer I stayed in England, the more I realized that how one speaks was critically important in that class-bound society. I quickly dropped all the Kiwi slang I ever knew. But, unlike Eliza Doolittle in “My Fair Lady,” I could not get my tongue around the inflections and tonalities that signified “proper” English. My accent slotted me into a pigeonhole labeled Colonial, from which I could escape only by leaving.