Archive for September, 2015

Translucent angels

The glass artist John Hutton was on the list of New Zealanders living abroad that my editor at the Christchurch, NZ Press handed me when I left the paper in 1962. “He’s been working for years on a project for the new Coventry Cathedral. Go check out how it’s going,” he said.

Also known as St. Michaels, the original cathedral in Coventry, England was constructed between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. It was gutted by incendiary bombs during World War II; only the tower, spire, the outer wall and the bronze effigy and tomb of its first bishop survived. After the war, a decision was made to build a new cathedral and to preserve the ruins as a constant reminder of conflict, the need for reconciliation, and the enduring search for peace. The architect, Sir Basil Spence, proposed that the new cathedral should be built alongside the ruins, the two buildings together effectively forming one church.

Spence commissioned many magnificent art works for the new modernist building. Hutton’s contribution was to be a great glass screen for the west end of the new cathedral.

This image of Hutton’s great glass screen was posted by ashleyniblock on http://www.vortis.com/blog/

Unfortunately, the text of my interview is lost, but I still have a letter I wrote about our visit to Hutton’s studio near London:

May 9, 1962

One of the vases made by Hutton for sale at Coventry Cathedral. It is decorated with figures which appear among the images in the Great West Screen. It is now in the University of Warwick Art Collection.

Another artistic experience of a quite different sort was on Monday – we went out to interview John Hutton, a New Zealand artist who has made the great glass screen for Coventry Cathedral, which is to be consecrated this month. The panels are engraved with saints and angels, in a very bold scribbly style that nevertheless has a rich Gothic quality about it. We were very impressed, and also with his other work that he has at his studio – more glass work, but also paintings, and many other media as well. Just wish we had a hundred pounds to spare – he is making a series of vases, each engraved with two of the angels, which the cathedral is selling to raise funds.

Revisiting this story feels particularly relevant today. From the window of my office at the Christchurch Press, I used to look out at ChristChurch Cathedral, which was destroyed in the earthquake of 2011. Arguments are still going on about whether to rebuild or replace a building that was the physical and spiritual center of the city.

Great music stays in the mind

I fell in love with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau when as a college student I heard his glorious baritone caress Schubert lieder in Christchurch’s boxy old Town Hall. I fell in love again when Mstislav Rostropovitch strode onto the same stage and plunged immediately into a Brahms cello sonata.

I fell in love with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau when as a college student I heard his glorious baritone caress Schubert lieder in Christchurch’s boxy old Town Hall. I fell in love again when Mstislav Rostropovitch strode onto the same stage and plunged immediately into a Brahms cello sonata.

From an early age, music has been an important part of my life. At the age of thirteen I was playing second violin in my home town’s municipal orchestra. We weren’t very good, but we were ambitious; the major work of my first concert was Beethoven’s 5th Symphony.

In Christchurch I played in the Canterbury University orchestra, and discovered the joys of playing Bach as an ensemble, of listening for the counterpoint of continuo and chorus in one of his great chorales.

I never seriously considered a career in music, but have continued to be an enthusiastic listener, going to as many concerts at budget allows. So it was with great excitement that my husband Tony and I explored London’s musical offerings when we arrived in 1962. Re-reading the letters to parents saved in my old black filing cabinet, I see that nearly every one contains mention of some musical event.

April 9

[At Westminster Abbey] While we were there a choir and orchestra were having a final rehearsal of Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion.”

April 28

On Good Friday we attended a performance in the Royal Festival Hall of Bach’s St. Matthew Passion by the London Choral Society. … We went there again on Wednesday evening for an all-Mozart concert, and we were sitting in the choir seats behind the orchestra – a favourite place for music students, as you get a wonderful view of the conductor, and feel right in the orchestra.

May 9

Last night we went to the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden – doesn’t that make your mouth water? It started off with a few divertimenti – rather pretty and fluffy, and the a very fine performance of “Les Sylphides” with the Russian dancer Nureyev stealing the show – you remember he defected from Russia some time ago. But the reason we went was for Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring” – tremendously exciting, jagged and violent. In spite of the narrow benches in the gods, where you knees dug into your neighbour’s back, it was a great thrill to be there. Covent Garden seems to be a place for the dedicated ballet enthusiast – you rarely hear an audience go quite so crazy at other forms of entertainment. Outside the opera house is fruit market – it was quiet at night, but the smell of fruit was everywhere, and we walked down through the trucks and piles of cases back to the Strand.

May 25

Went to Bertrand Russells’ birthday party last Saturday, in the Festival Hall. Concert by the London Symphony Orchestra – one of the finest performances of Mozart’s 39th Symphony that I have ever heard. Also Lili Kraus in a very impressive performance of a Mozart piano concerto. Lots of speeches etc. too – made us realise what an outstanding leader Russell is.

The music comes back to me as I re-read my letters, and I recall what a wealth of culture London had to offer.

Movies for the intellectual set

“I’ve seen Last Year at Marienbad seventeen times already,” our college friend Bill told us as he showed us around London on our arrival in 1962. “I still haven’t figured out what really happened. I’ll have to go again this weekend.” This enigmatic movie, directed by Alain Resnais and Alain Robbe-Grillet, is considered a masterpiece of the French New Wave. The movie website rottentomatoes.com comments: “Elegantly enigmatic and dreamlike, this work of essential cinema features exquisite cinematography and an exploration of narrative still revisited by filmmakers today.”

For my husband Tony and me, it exemplified the rich cultural life we discovered in London. In New Zealand, where we grew up, to be an intellectual was to live as a small coterie on the outskirts of society, viewed with suspicion by the mainstream. To be an intellectual in London was to be part of a big vibrant conversation, fueled by articulate reviews of movies, books, art exhibitions, plays and dance performances in the Sunday Times and other papers. In between job hunting and flat hunting, we took the opportunity to participate as much as possible.

Reading again a letter to parents dated April 18, 1962, not long after we arrived, I note a distancing of myself from this new world of ideas, possibly a Kiwi reluctance to admit my eagerness to be part of it. I wrote:

London is chockfull of fascinating characters – you meet them everywhere – on the street, in the Underground. All sorts and shapes and sizes. We met the intellectual set last night – went up to a cinema at Hampstead Village – on the edge of the Heath – which is obviously run by and for the intellectual crowd – hard red and black in the décor, and the finishing touch a handsome beaten copper plaque for the exit sign. They have been showing a series of all Ingmar Bergman, the modern Swedish director’s films. The place was packed out with long hair and beards and intense faces. Almost as interesting to watch as the film. It was a very delicate and charming piece called “Smiles of a Summer Night.” We also saw another interesting film the other night – Alain Resnais’s “Last Year at Marienbad” – highly psychological (and apparently the intellectuals’ current talking-point!) The story (if you can call it that) is that a woman meets a man at a spa who tries to convince her that they were intimate there the previous year, but she thinks she has never seen him before. Scope for highly intriguing playing around with time and facts, with emotional distortions.

London is chockfull of fascinating characters – you meet them everywhere – on the street, in the Underground. All sorts and shapes and sizes. We met the intellectual set last night – went up to a cinema at Hampstead Village – on the edge of the Heath – which is obviously run by and for the intellectual crowd – hard red and black in the décor, and the finishing touch a handsome beaten copper plaque for the exit sign. They have been showing a series of all Ingmar Bergman, the modern Swedish director’s films. The place was packed out with long hair and beards and intense faces. Almost as interesting to watch as the film. It was a very delicate and charming piece called “Smiles of a Summer Night.” We also saw another interesting film the other night – Alain Resnais’s “Last Year at Marienbad” – highly psychological (and apparently the intellectuals’ current talking-point!) The story (if you can call it that) is that a woman meets a man at a spa who tries to convince her that they were intimate there the previous year, but she thinks she has never seen him before. Scope for highly intriguing playing around with time and facts, with emotional distortions.

Over the next few years, we saw almost all of Ingmar Bergman’s movies, which I still love, along with many by the French New Wave directors. I learned to accept that I too was an intellectual.

Over the next few years, we saw almost all of Ingmar Bergman’s movies, which I still love, along with many by the French New Wave directors. I learned to accept that I too was an intellectual.

Droplets in an immigrant wave

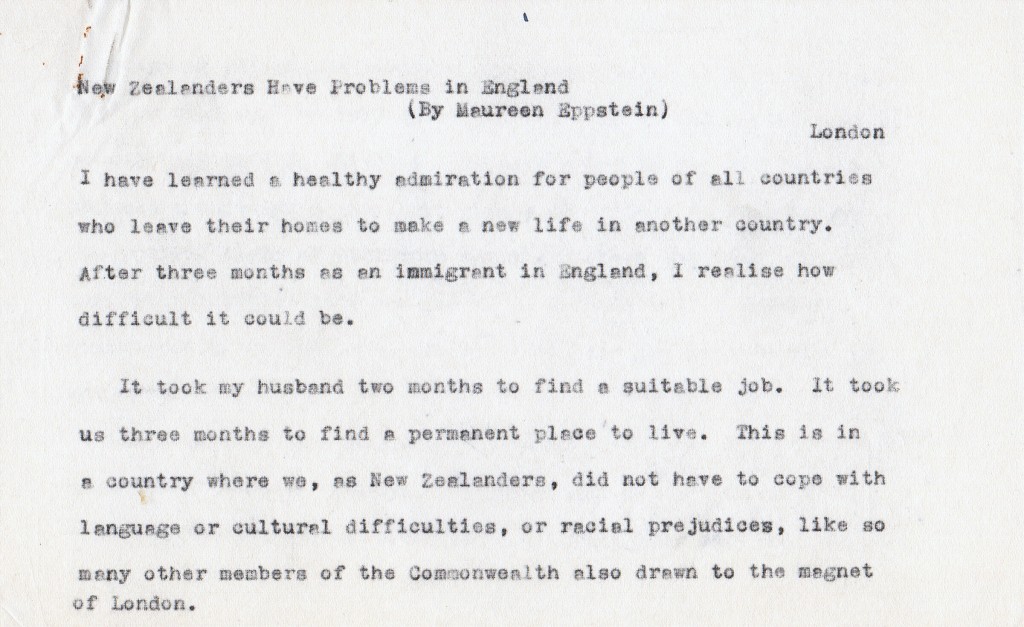

In a 1962 article I wrote for my old paper, the Christchurch (NZ) Press, a draft of which I found in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

I have learned a healthy admiration for people of all countries who leave their homes to make a new life in another country. After three months as an immigrant in England, I realize how difficult it could be.

It took my husband two months to find a suitable job. It took us three months to find a permanent place to live. This is in a country where we, as New Zealanders, did not have to cope with language or cultural difficulties, or racial prejudice, like so many other members of the Commonwealth also drawn to the magnet of London.

We had no idea at the time of the hugeness of the immigration wave in which we floundered. To aid in post-war reconstruction in the 1950s, Britain had recruited labor from its colonies, primarily the West Indies and the Indian sub-continent. At that time people from the Empire and Commonwealth had unhindered rights to enter Britain. However, by the late 1950s, with the British economy faltering, racial prejudice reared its violent head. The Conservative Party government proposed legislation to make immigration for non-white people harder. One aspect of the proposed bill was to deny entry to dependents of immigrant workers. Before the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 could go into effect, the entry of dependents into Britain increased almost threefold as families attempted to beat the deadline. Total immigration from what was known as the New Commonwealth swelled from 21,550 in 1959 to 58,300 in 1960 and a record 125,000 in 1961.

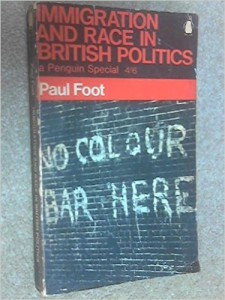

Statistics are from Paul Foot, Immigration and Race in British Politics (Penguin, 1965)

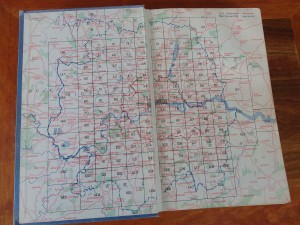

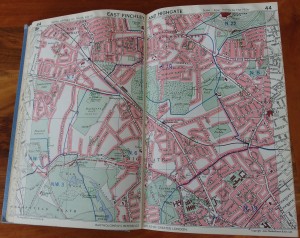

All these people needed somewhere to live. It is no wonder then that rents soared and accommodations of any sort were snapped up. While Tony job-hunted, I haunted rental agencies for a short-term apartment (or flat, as they’re called in England) and, the hefty Bartholomews Atlas of Greater London under my arm, braved the Underground and navigated the suburbs. My letters to parents are full of observations like this one:

It’s amazing how so many of the little villages that have been absorbed into the city still retain their village atmosphere – you pop up from an Underground station and could imagine yourself miles out in the country – unless you happen to be on a bit of a rise, when you see nothing but houses as far as the eye can see. One place I visited, for instance, Muswell Hill, you had to go by bus through a very extensive patch of woodland to get to it. That place I didn’t take, incidentally, because the bath was in the kitchen – covered by a lift-up board and a little frilly curtain. When I mentioned this to another English landlady she didn’t even raise an eyebrow.

My letter continues:

We have now moved out of our hotel into a bedsitter out at Hampstead, for which we are being grossly overcharged – I guess we just took it in a moment of desperation.

The rent was six and a half guineas a week (the same buying power as about $200 in current U.S. dollars.) Every piece of furniture was shaky about the legs, and the cooking facilities were two gas rings crammed into a cupboard with about six inches of counter surface. The shared bathroom was down the shabby hall. I described the landlady as

a bit of a social type – she was too busy preparing for her cocktail party last night to attend to our wants, which brassed me off considerably. Still we get on quite well with her little dog, so with a little careful handling relations might improve.

Relations did not improve. Still vivid in my mind is one of our shouting matches. I had returned from the local laundrette with clothes still damp, in spite of multiple coin feeds to the drier, and had strung clothesline around the room. In walked Mrs. Ashley-Davis. “My furniture! My furniture!” she wailed, hand to her heart. Other disputes must have followed. In a letter to parents dated May 25, after giving the news that Tony had accepted a job near Windsor, I mention that we have given notice

…after some somewhat violent disputes with the landlady, in which I managed to lose my temper – catastrophe!

Finding permanent housing proved even more frustrating. I told my parents:

…for the last three or four days we have been footslogging, railriding, bussing, and generally getting fed up in a wide arc around the area…

We moved out to a hotel near Tony’s new job. My letters for the next few weeks are full of the false hopes and discouragements of the search. Finally we got lucky: a second floor flat in a Victorian brick semi-detached house just down the hill from Windsor Castle. A roof over our heads at last!

Here’s a modern Google Maps street view of the neighborhood. It still looks much the same.