Archive for October, 2015

A single knitting needle

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The significance of the knitting needle did not dawn on me at first. I found it under the bath tub, buried in a mound of dust balls, while I was cleaning the flat we has just moved into, in Windsor, England, in 1962.

The flat was part of a semi-detached house dating from the 1870s. The bathroom could have been original. The floor was covered in black and white checkered linoleum, worn white in front of the chipped hand basin. Above the claw-foot tub was a rusty gas-fired contraption that roared to life when you turned on the faucet. The toilet was down the hall, in a more recent addition to the building.

That knitting needle haunted me, as gradually I came to realize it was probably the instrument of an attempted abortion. I longed to know the story of the woman who had pushed it through the crack between the tub rim and the wall. Did she survive?

The conservative New Zealand society in which I grew up had such deep silences around anything to do with sexuality that I was nineteen before I even encountered the word “abortion.” It was in a letter from my mother. “Look it up,” she wrote, her stock response to any question having to do with the body. Mum’s news was that a girl I knew in high school was dead: a move to the city, an affair with a married man, a botched back street abortion, septicemia, the police phoning her parents, saying contemptuously Come and get your kid.

I too have known the desperation of an unwanted pregnancy. I went into marriage in 1960 with what today would seem unbelievable ignorance about sex. The kind ladies at the Planned Parenthood clinic in Christchurch fitted me with a diaphragm and instructed me in how to use it. But the contraceptive methods of those days had a high failure rate. Within a month of the wedding I was pregnant. My new husband was furious with me for stymying his plans to go abroad and make his name in science. I was terrified of the alien life form taking over my body. I tried to recall from novels I’d read how female characters sought to make missed periods come. Scalding hot baths—I tried that. Long, long walks—tried that too, into the seedier parts of the city. If I were to find an abortionist, it would be here. But I had no idea how to find one, and no-one to ask. Besides, I didn’t want to die, like my high school friend.

In time my resistance eased. I was, after all, a respectably married woman. I began to look forward to having a baby. My husband and I postponed the date for our departure to England, and informed the shipping company that we would be traveling with an infant. When our daughter was stillborn, I was devastated, both by the loss, and by the thought that I was being punished for not wanting her in the first place. I buried my grief and guilt deep inside and got on with my life. It took me twenty-five years before I could speak about what had happened, and finally begin to mourn.

In California in the early 1970s I made the acquaintance of a lawyer who had filed an amicus curiae brief in Roe vs. Wade. Together we celebrated that important Supreme Court decision, which affirmed a woman’s right to control her own body. Today I am dismayed that so many people seem to have forgotten, or maybe never knew, what the options were for women when abortion was illegal. The decision to end a pregnancy is never easy. But I, for one, don’t want to go back to the days of the knitting needle hidden under the bathtub.

All a poet can do is warn

All a poet can do today is warn.

–Wilfred Owen

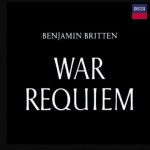

Cream plastic transistor radio close to my ear, I sat by the window of our London bedsitter, hearing familiar words set to brand new music: the premiere of Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem”. The May 30, 1962 performance was part of a festival to mark the consecration of St Michaels Cathedral in Coventry, a new modern building set alongside the bombed-out ruins of the old.

I had a personal interest in the cathedral, since one of my assignments for my New Zealand newspaper had been to interview the glass engraver John Hutton, one of the many eminent artists whose work graced the new building.

I was also caught up in the prevailing excitement about the completion of this significant architectural and spiritual project. Contained within the walls of the new cathedral was the idea of reconciliation, that it would be a place that would, in the words of the cathedral website, play a part in

Healing the Wounds of History

Learning to Live with Difference and to Celebrate Diversity

Building a Culture of Peace

But mostly my interest was in the poetry of this new musical work. I had been introduced to the poems of Wilfred Owen in high school. A soldier who died on the battlefield in the last week of the first World War, he wrote searing indictments of that war’s ravages. To me as a student, it was a revelation that poetry could be used to express such pain and anger.

I already had some familiarity with Britten’s music, but I was blown away by the “War Requiem”, which interweaves Owen’s poems with the traditional Latin of the requiem mass. I was brought to tears by Britten’s handling of Owen’s poem of reconciliation, “Strange Meeting,” in the concluding section of the work. In the poem, Owen imagines two dead soldiers, one English, one German, who meet each other

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined

They share life stories:

Whatever hope is yours,

Was my life also; I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world

…

I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled

…

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

The poem ends with the line Let us sleep now … which Britten repeats and extends in a hypnotically murmuring lullaby.

I have listen to the “War Requiem” many times since that memorable evening in London. It still brings me to tears.

A 1963 audio CD of the War Requiem, featuring the soloists for whom it was written, Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Galina Vishnevskaya, is available on Amazon.

A 1963 audio CD of the War Requiem, featuring the soloists for whom it was written, Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, and Galina Vishnevskaya, is available on Amazon.

The Poetry Foundation website has a good selection of Wilfred Owen’s poems.