Archive for July, 2016

Pregnancy under a national health system

My old black filing cabinet has yielded up a statistical treasure: an article I wrote for my New Zealand newspaper about the National Health Service’s maternity benefit program in England in 1963. I was pregnant at the time, and financially stressed, so the detailed information was particularly relevant to me. I was also young and impatient with bureaucracy, hence my railing about what seemed excessive form-filling. Keep in mind that the British pound numbers need to be multiplied by 30 to get an approximate equivalent in current US dollars.

A CHILD OF THE WELFARE STATE

Having a baby in England is a (welfare) state occasion. From the moment that a pregnancy is confirmed, an expectant mother can expect to be cared for by the state in practically every detail, down to a monetary allowance for buying clothes.

The services provided are similar in many respects to those in New Zealand [which also has a national health system]. The main difference seems to lie in the number of forms requiring to be filled out for every aspect of care. When she goes to her doctor, the woman will have already filled out a form applying to be placed on the doctor’s list, and she will have received a national health card, which she presents at each visit.

It will have to be decided where the baby is to be born. Unlike New Zealand, where admission to a maternity hospital is practically automatic, most babies in Britain are born at home. Recent reports have suggested that the infant mortality rate could be greatly reduced if more babies were born in hospital, but this raises the problem of inadequate bed space. Some effort is being made by the government to increase the number of hospitals, but it is clear that for many years yet admission to a maternity unit will be restricted to those who have good medical reasons for being there. Next in order of preference are those whose homes are inadequately provided with such facilities as running water. It is usually considered advantageous to have a first baby in hospital, although this is not always possible, and space is provided where possible for mothers having their fourth or later children.

If the baby is to be born at home, ante-natal care is provided by the family doctor and the midwife who will be attending. If the mother is granted a place in a hospital, she goes to the clinic which is run by a team of doctors and nurses from the hospital. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Expert specialised attention is given at the clinics, compared with a family doctor who may, or may not, be deeply interested in obstetrics. Against this are the advantages of seeing the same person at each visit. It is quite possible to see a different doctor at each visit to a large clinic, with the resultant irritating repetition of questions. This lack of rapport, as well as the great pressure of time on the clinics, hinders many women from asking the questions that may be troubling them. The government recently released plans to set up more clinics, which may relieve the pressure a little, but it is difficult to see how much of the mass-production atmosphere can be avoided.

During her pregnancy a mother is provided with several benefits from the state. She receives free dental treatment: normally dental patients contribute the first ?1 of their dental bills, and the health service pays the rest. She receives welfare foods—a pint of milk a day at about half price during her pregnancy, and until her child is five years old. The health service’s own brand of dried milk is provided where necessary. She is also offered cheap orange juice, cod liver oil, or vitamin A and D tablets. These products are free to those who apply to the National Assistance Board claiming hardship.

The state also provides cash benefits. To allay the hardship often suffered when a married woman gives up her job to have her first baby, and to make it easier for her, in the interests of herself and her baby, to give up work in good time before the birth, the state pays her an allowance of ?3 7s 6d a week. To qualify, she must have been paying the full rate of national insurance. It should be explained that health benefits are not paid directly from taxation, as in New Zealand, but from regular weekly contributions to a national insurance scheme. It is possible for a woman, when she marries, to contribute only a nominal sum to the scheme, and to claim on her husband’s contributions for medical benefits. However, if she chooses, she can continue to pay at the single rate, and thus become eligible for these extra benefits.

All mothers, whether working or not, are given a cash grant of ?16 to help with the general expenses of having a baby. A further sum is paid if more than one child is born. In addition to this, those women who have their babies at home are given a home confinement grant of ?6 towards the extra equipment needed.

Needless to say, all these benefits depend on the filling in of forms, and presenting them at the right time. The time limit for each benefit varies, but local national insurance offices are usually helpful about coping with the confusion.

Once the baby is born, the state’s child welfare service, under the local Medical Officers of Health, takes over. This provides a service similar to New Zealand’s Plunket Society, on a nationalised level. The child welfare service is notified by the hospital or midwife of the birth, and within a few days a health visitor calls to take particulars. (Why do they always want to know the husband’s occupation?) She also gives details of the local child welfare clinic, which provides a weighing service, and advice on feeding and other problems.

Home help services are also provided, to look after children while the mother is in hospital, or to help the mother in the home.

For those who can afford to dislike the mass production methods of the national health service, there is an alternative in private treatment. Private maternity hospitals are not subsidised as they are in New Zealand, and attention by an obstetrics specialist and delivery in a private hospital would cost at least ?100 in England, and probably much more. But even with private attention, the patient is still entitled to the maternity grants and welfare foods.

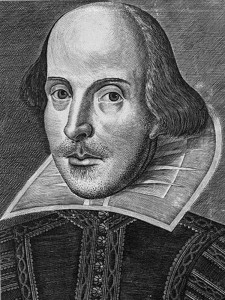

A Shakespearean ghost and an old tree

Herne’s Oak, Windsor Park circa 1799

Etching with hand colouring, attributed to Samuel Ireland (1744-1800). The two Merry Wives of Windsor, Mistress Page and Mistress Ford, are standing with Falstaff at Herne’s Oak.

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

In the grounds of Windsor Castle in England stand thousand-year-old oaks so huge and gnarled and blasted it’s easy to imagine them haunted by spirits. Shakespeare used this conceit in his play “The Merry Wives of Windsor.”

When I was a Windsor wife in the early 1960s , I attended a performance by the Windsor Repertory Theatre of “Merry Wives” one summer evening in the castle gardens. Probably written to amuse Queen Elizabeth I, the play uses as its setting then-familiar Windsor landmarks, such as the 14th century Garter Inn on High Street and Herne’s Oak in Windsor Great Park.

The play centers around the drinker and gambler Sir John Falstaff, known from the plays Henry IV part 1 and part 2. Short of money, he comes to Windsor where he attempts to seduce both Mistress Page and Mistress Ford in hope that at least one of them will share her husband’s wealth with him. He writes each wife an identical letter, but the two women, who are close friends, immediately show each other their letters and are outraged.

The wives decide to teach Falstaff a lesson, and pretend to lead him on while planning his downfall. He is dumped from a laundry basket into the muddy River Thames, and beaten while disguised as the Old Woman of Brentford, who is believed to be a witch. With their husbands in on the secret, they concoct a final revenge for his clumsy insults to their virtue. Mistress Page sets the scene:

There is an old tale goes that Herne the hunter,

Sometime a keeper here in Windsor Forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree, and takes the cattle,

And makes milch-kine yield blood, and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner.

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Receiv’d, and did deliver to our age,

This tale of Herne the hunter for a truth.

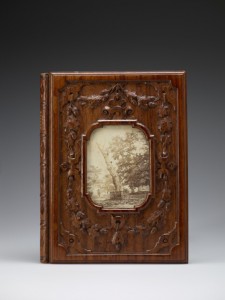

Cover of William Perry’s “A Treatise on the Identity of Herne’s Oak, Shewing the Maiden Tree to Have Been the Real One”

Probably presented to Queen Victoria by William Perry, c. 1867

Drawings Gallery, Windsor Castle

Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2016

The Royal Collection website notes:

Perry’s treatise claiming the authenticity of this tree echoed Queen Victoria’s own belief, though his view was not entirely unbiased since he had been given portions of the wood to carve into souvenirs, which include the binding of this book. A photograph of the tree shortly before its fall is inserted in the front board.

Falstaff is induced to dress as the ghost of Herne the Hunter and wait for the two women at Herne’s Oak, where he is pinched and tormented by local children dressed up as fairies.

Since Herne’s Oak has now fallen, exactly which tree it was—the one that fell in 1799 or the one in 1863—remains in dispute. Also unclear and undocumented are the origins of the myths about Herne the Hunter. Shakespeare was the first writer to mention him. His purported connection to ancient archetypes representing the primal power of nature may be an artifact of Victorian story-makers. Some evidence suggests there was a real game-keeper in Windsor Great Park named Herne or Horne, possibly in Elizabeth I’s time, possibly earlier, who, having committed some great offence for which he feared a dreadful punishment, hanged himself on an oak tree. Maybe Mistress Page had it right: the memory of such an event at a scary-looking tree could be enough to start a legend about a ghost.