Archive for October, 2016

Fingernails on glass

The visiting baby, almost two years old, sat alone and silent by the ribbed glass door of our row house in Egham, on the outskirts of London. He paid no attention to our chatty, energetic infant of the same age, nor even to his parents. Instead, he ran his tiny fingers obsessively over the ribs of the glass. Watching him as I fixed tea for our guests, I was uneasy.

A letter to my parents dated 20 April 1965 says nothing of this unease. Instead:

We had visitors on Sunday – Steve & Derek Shirley & their little Giles, who is the same age as David. We hadn’t seen them for quite a while, & had a very pleasant day.

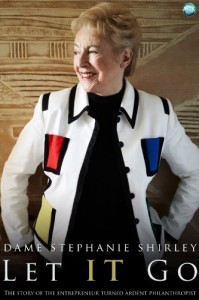

That was the last time we saw the Shirleys. Recently I have been reading Dame Stephanie (Steve) Shirley’s memoir Let IT Go, to try to understand what happened to our year-long friendship. The answer is devastating.

In early 1964 I had interviewed Steve by phone for an article that ran in the Guardian about women programmers and her new business Freelance Programmers. A few months later I gushed to parents:

30 April 1964

A couple of weeks ago we went to visit a very pleasant couple – the woman I interviewed (over the telephone) for my article on computer programmers. She has a baby the same age as David, and also works at home making up programmes – that is, the detailed instructions to be fed into a computer to do a required job. Anyway, we liked each other very much even over the phone, and she invited us to a meal to meet properly. They have a marvellous little stone cottage up in the Chilterns, right out in the country, with apple trees and daffodils, low oak beams, a huge log fire, and a grand piano squeezed into the front parlour. It sounds like a setting from a romantic novel, and that was the feeling even when we were there, that everything matched so well that it couldn’t be quite real. And a remarkable affinity too, between us as people. A bond to start with of course — it was the interest of her story that got me a place in the Guardian, and she credits me with the terrific boost to her business – she now has 20 other home-bound women working for her, and is forming herself into a limited company, and with giving her the confidence to get started. Then Derek is also a physicist [like Tony], reserved, very musical, and Steve and I found that our feelings and ideas agreed on all sorts of points.

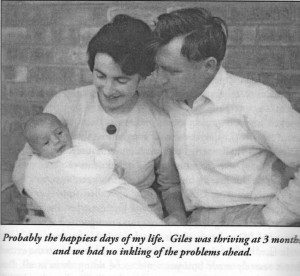

At that time Giles and our David were eleven months old. Steve writes in her memoir:

The catastrophe had crept up on us. It must have been in early 1964—when he was about eight months old—that we first began to worry, on and off, that perhaps Giles was a bit slow in his development: not physically, but in his behaviour. He was slow to crawl, slow to walk, slow to talk; he seemed almost reluctant to engage with the world around him. These concerns took time to crystallise—as such concerns generally do—and the first time I went to a doctor about them I couldn’t even admit to myself what was worrying me. …

My letters for the rest of 1964 are full of references to our new friends: visits back and forth, parties, conversations. In June I wrote: We liked them even more, if possible … isn’t it strange how people sometimes just click.

Meanwhile, Steve writes:

By the end of that year, however, there was no avoiding the observation that Giles was losing skills he had already learnt. … [He] had never become chatty. And now he fell silent. …

Months of desperate anxiety followed, in which there seemed to be little that we could do except fret. …

My lovely placid baby became a wild and unmanageable toddler who screamed all the time and appeared not to understand (or even to wish to understand) anything that was said to him…

By mid-1965 Giles had taken up weekly residence at The Park [the children’s diagnostic psychiatric hospital in Oxford] while the doctors there tried to work out what was wrong. Nothing I can write can capture the enormity of the sorrow that that short sentence now brings flooding back to me. …

Finally, in mid-1966, the specialists overseeing Giles’s case [at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children] delivered the devastating but unarguable verdict: our son was profoundly autistic, and would never be able to lead a normal life.

I understand now that our friendship with the Shirleys could not survive. Being with us would have been painful for them. There was too much unspoken, too much contrast between their child and ours. For a short time, we loved them. Even now, a sadness returns.

Postscript

Derek and Steve spent the rest of Giles’s short life seeking appropriate and supportive care for him. (He died at age 35.) Steve’s business flourished. She has poured her considerable wealth into philanthropy, primarily to support “projects with strategic impact in the field of autism spectrum disorders.”

Dame Stephanie Shirley: Let IT Go, Andrews UK Ltd., 2012

Furnishing a house, 1960s style

A magazine clipping tumbles from a November 1964 letter from England to my parents. It’s the picture of a dinner service I won in a menu-planning competition. Looking at the geometric pattern on the dishes, I realize that the way we furnished the row house we bought that year has many elements of what is now recognized as a distinctive 1960s aesthetic: bold shapes and strong colors.

Having limited funds, Tony and I refurbished or made many pieces of furniture. The dining table he made was a heavy white plastic-veneered slab with straight, varnished wood legs. He built, and I upholstered, a sofa and side chairs with squared-off, simple lines, a copy of a set we particularly liked, but whose price was prohibitive. I made all the curtains from fabric purchased at Heal’s of London, the store that carried the trendiest of household furnishings. I wrote:

8 August 1964

The sitting room curtains are quite magnificent – deep orange flame colour, with a pattern called “Armada,” the formalised ships’ hulls giving the impression of a dark horizontal stripe.

A shag (another 1960s design element) area rug that matched the curtain’s colors helped warm up the coldness of the room. After battling the developer over the house’s color scheme, we had compromised on gray vinyl tile floor and plain white walls. In the kitchen and dining area, we covered the white with a geometric wallpaper. A photograph reveals more geometrics: the gray and white kitchen curtains, the cups and saucers on the counter.

We still have one platter from that dinner service I won. A few other items, mainly metal, have survived the years. A pewter jug purchased on board ship during our emigration from New Zealand to England still sits on our kitchen windowsill. To the right of the dinner service picture, behind a porcupine of cheese chunks on skewers, are familiar objects: salt and pepper shakers just like the ones we still use every day. I guess we, like these furnishings, can all be labeled “vintage.”

A long, slow saga of first-time house buyers

In 1964 my husband Tony came into an inheritance, enough to put a down-payment on a small row house in a village on the outskirts of London. From first placing a ?50 holding payment on a partially-built structure to actually moving in took seven months. Today, with the purchase, remodeling and/or building of four subsequent houses behind me, I read my letters to parents from that period with wry sympathy, thinking how universal is the impatience of a young couple buying their first house.

The first letter in the series has a page or more of excited detail.

11 May 1964

… though still with the nagging doubt that it is all too perfect, that something is sure to go wrong. Points in favor: a brand new house within our price range (rare), architect-designed with imagination (also rare), less than a mile from Tony’s job, practically in the country with a charming view over open fields to woodland, closer to London (20 minutes by fast train to Waterloo) and won’t be finished for three months by which time we should have the means to pay for it…. Small, of course, but with ingenious use of space and attractive layout …

When I was growing up, my mother filled binder after binder with house design ideas and plans. We (my parents, three children, and succession of boarders – aunts, uncles, and family friends, often two at a time) lived in a rental Craftsman bungalow built about 1910: two bedrooms and a sleeping porch accessible only through the parents’ bedroom and through a laundry room in which a toilet was installed late in our tenure. (Before that, we used the outhouse back in the yard.) Mum eventually built her dream house when I was about thirteen. In the meantime, I learned a lot about building design and became very familiar with architectural drawing and its symbols. I drew her a sketch:

After a month of marking time, and a thickening correspondence file, a tirade about a building society (English equivalent of a mortgage company) to whom we had applied:

8 June 1964

… the building society wouldn’t consider our house for a mortgage because it was too contemporary in design – they stick doggedly to the deadly dull conventional things. We saw one the other day, part of an estate quite near here – good solid brick, appallingly bad planning, and claustrophobically tiny windows. Mortgages no bother.

A month later, good news on the offer of a loan from another building society. However, letters for the next several weeks report a battle with the developer:

30 July 1964

… One of the hazards of a speculative development – they are very reluctant to depart from the standard model, which in this case is decidedly murky – masses of dark grays, black, browns & blues. I’m getting a bit fed-up – sick of looking at samples & doing sums – I want some action round the place.

8 August 1964

… ran into trouble over the alterations we wanted to the colour scheme – we were met with a blunt ‘take-it-or-leave-it.’ However, eventually Tony rang up & told them they were a lot of bloody-minded so & so’s, & managed to get the most important concession – the colour of the tiles on the floor. The rest of the detailing we shall probably have to rip out & replace as we can afford it. Infuriating, but the housing situation being what it is, we daren’t tell them to go to hell.

Inevitably, construction delays kept postponing the finish date for the house:

26 Sept. 1964

We went up to London on Tuesday to sign the lease & mortgage documents for the house. Exciting, but still somewhat unreal. I am ceasing to believe in the existence of the house, and find it rather unsettling to go over every other weekend or so & find they have done a tiny bit. Still no idea when we can shift in – it will probably be weeks yet.

8 December 1964

It is still hard to believe that we have actually moved in. Up to 9:15 on Friday morning, with the carrier already piling boxes into the van, we still didn’t know if we could – it all depended on the cheque from the building society being in our solicitor’s post. A strange, unreal situation to live through. However, talking to some of the other people who have moved in, they seem to have had much more trouble than us, so we must be thankful.

Anyway, in all the chaos of cancellations, postponements, etc., it was too much trouble to cancel our housewarming party, so we held it as planned on Saturday night. The earliest arrivals were detailed off to put up curtain rails, shift packing cases from the middle to the sides of rooms, etc. Quite a successful party, I think. About a dozen people (& kids) stayed overnight, dossing down wherever for what was left of the night – we got to bed about 4 am, & a few more people dropped in for brunch the next morning. Needless to say by today we are both pretty worn out, but the house is more or less habitable. Strange what an effort, both physical & mental, to make a shell filled with boxes into a habitable room.