Archive for January, 2017

Fight or flight: an expatriate ponders

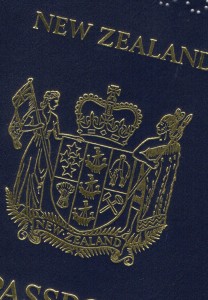

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

Since the election, my husband has been suggesting that we renew our New Zealand passports, expired nearly forty years. Though we are fortunate in having dual citizenship, I am reluctant. I love my life and my friends here in Northern California, and want to stay and fight for what I value. “It’s just an insurance,” he says. Just in case the unthinkable happens.

In this period of political unease in the US, when many have expressed a wish to go live somewhere else, I think back to our last few years in England in the mid-1960s, and how alienated we felt then.

An economics text for UK students cites several reasons for the dour mood of the country in those years. Author Tejvan Pettinger writes:

Despite higher economic growth, the UK performed relatively poorly compared to major competitors. UK productivity growth was relatively lower due to several factors. such as:

- Lack of willingness / ability to innovate

- Poor industrial relations with a growing number of days lost to strike action. Some argue this was exacerbated by Britain’s class system.

- Trade unions effectively blocked efforts at reform.

- Complacency.

- Lack of public sector infrastructure.

Even though we might have returned to New Zealand then, our lives did not take that turn. In my old black filing cabinet I found a letter to my parents that lays out the situation.

19 July 1966

… [W]e are still unsettled about what we are going to do with ourselves. We did have serious ideas of returning to New Zealand, but I am afraid that is now dropped through lack of interest on the part of N.Z. firms. We are feeling rather sour about the whole affair, especially as N.Z. is always griping about the country’s young brains staying away in their thousands. A year ago Tony made a private enquiry to I.C.T. (NZ) asking about the prospects of getting a job, and did not even get the courtesy of a reply. Then six months ago head office in London offered to arrange a transfer for him. After much prodding, official letters to N.Z. eventually got answered, but in such unsatisfactory terms that no-one knew quite what they wanted. It has taken six months for N.Z. to agree to take Tony, but they have made it plain that they consider he is being foisted on them by London, and that they are still suspicious of him. Their terms are that he is to have a year’s training in computer systems, and not until “they see how he gets on with the training” will they consider discussing position or salary. Since Tony is one of I.C.T.’s top authorities on computer tape, and already has a big general background in computer systems, he has taken this as a not-so-polite brush-off and told them what they can do with the job. If he were in his early twenties, without family, and determined to get back, it might have been different. But at his age—rising thirty is a critical age in his line of industry, since the job decisions he takes now will set the line his career is to take. So you see he just can’t afford to throw away yet another year on a job that might still not eventuate, and would probably be a frustrating backwater if it does. Other computer firms in N.Z. take much the same line—not interested enough to get him an interview in London, just “drop in when you get to N.Z. and we will see if there is anything doing.”

Meanwhile, he is still negotiating for a job with an American firm, which might mean going to live in California, but nothing has been settled yet, We feel it is time we got out of this country—the present economic crisis is just a symptom of a general decadence and backward-looking attitude, and we can’t see any future for Britain.

You mentioned your feelings towards Britain as a spiritual home—I can understand this, and think it is one of the main forces that pushes young people into coming over here. I think it is this thing about historical roots—it gives a wonderful sense of history and continuity to visit places that have been lived in for so long by so many different peoples. But it is necessary to distinguish between this feeling and the present political reality. Modern Britain doesn’t care two hoots about New Zealand—it is either confused with Australia (well, they are both on the other side of the world, what does it matter?) or else N.Z. is regarded as some sort of idealised paradise where it is never rainy or cold, and where they would like to go to escape from reality. As a political or economic entity it just doesn’t exist. And while N.Z.ers continue to believe that it doesn’t exist either, except as an offshoot of Britain, there is not much hope for its future, and the young brains will continue to stay away in their thousands.

Which makes us more or less permanent exiles, at least spiritually. But if we do go to America, it is probable that Tony will be earning enough money for us to afford the occasional holiday in N.Z. I feel very sad that the children do not yet know their grandparents, but that is one of the penalties of our decision. I hope you will understand.

Robin redbreast on a fence

I still ponder why it meant so much, that Christmas morning in England in the 1960s, that a robin sat on the back fence. The field behind the fence was white, the fence wires thick with hoar frost, and the little red-breasted bird made the scene perfect. Finally, I told myself, a ‘real’ Christmas.

I have tried for many years to clarify my feelings about the disconnect between the traditional trappings of the season and my experience of growing up in New Zealand, where the seasons are reversed. My childhood Christmas memories are of summer: the tree laden with oranges in my grandmother’s garden where we hung our presents and picnicked on the lawn; the scent of magnolia blossom outside the church on Christmas Eve.

Also the Christmas cards with their images of snow (which I’d never experienced) and yes, the English robin. I knew about robin redbreast from the old nursery rhyme, but until that Christmas I hadn’t seen one.

Now on the coast of Northern California, I have a different understanding of how to celebrate the winter season. Our multicultural society recognizes many winter festival stories and traditions: the birth of Jesus in a stable, the menorah candles of Hannukah, the Swedish light-bringer St. Lucia, the gift-bringer St. Nicholas (known also as Santa Claus), and many others. The celebration that holds the deepest meaning for me now is Winter Solstice, the return of the light. From summer to winter, I note where on the horizon the sun sets, and how the darkness grows. Even as clouds gather, the place where sun disappears into ocean fogbank moves steadily to the south. When the prevailing westerly wind shifts to the southeast, I know to expect the winter rains. Sometimes a shower or two, sometimes, such as this past week, a prolonged deluge that floods rivers, downs power lines, and closes roads.

Meanwhile, the earliest spring flowers are breaking bud, and over-wintering birds gather hungrily at my feeder: Steller’s jay, spotted towhee, hermit thrush, acorn woodpecker, hordes of white-crowned sparrows. I love them dearly. I am happy that I have learned to understand the connection between the flow of seasons and human efforts to explain them with stories and festivals. And I still have a place in my heart for the memory of that cheery robin redbreast who brightened an English winter.