Archive for August, 2017

Uncles & cousins & aunts, oh my!

Recently, while reading Michael Krasny’s new book, Let There Be Laughter, I came across the Yiddish word naches, which Krasny defines as “the joy and pride a parent derives from a child’s accomplishments.” High on a mother’s list of accomplishments for her daughter would be the production of beautiful grandchildren. It was an ‘Aha!’ moment. I’d been re-reading some of my 1967-68 letters to parents (my mother saved them all and gave them back to me) and thinking about the strained mother/daughter relationship the letters revealed.

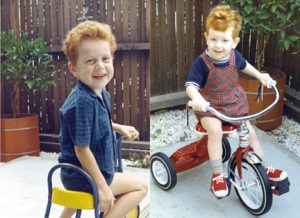

The occasion was our first visit back to New Zealand. It had been seven years since we left our birth country, and twelve years since I had spent more than a week or two with my parents. In the meantime I had earned an advanced degree, begun a career as a writer, married, moved to England, had a couple of children, moved to California. I had kept in touch faithfully through fortnightly letters but had had none of that face-to-face interaction that helps define a relationship.

I was wildly excited about the trip:

18 Sept. 1967

I have a bit of news that I have been saving up, partly because I still scarcely believe it myself – we are hoping to come for a visit to NZ about the middle of next year, probably in May. It will only be for a month – you get a cheaper excursion rate for 28 days – but hope that will be long enough to see everybody again, & for the children to sort out who all the vague names of grandmas, uncles, etc. are – David [our 4-year-old] has them hopelessly confused at the moment.

1 Oct. 1967

[On news that sisters & cousins were having babies] It will be fun to meet all these new members of the family – they certainly seem to be mounting up.

31 Oct. 1967

[re Christmas presents] Like you, finance is a bit low this year – as you can imagine, we are needing to save very hard for this trip.

My next letter has a firmer tone. With the help of a marriage & family therapist friend (thank you, Linda G.), I’ve been researching the psychology of mother/daughter relationships and discovered the Jungian concept of individuation, the process of becoming aware of oneself as a being separate from one’s parents. I also learned that tensions are normal in the parent and adult child relationship during this process of separating and setting boundaries.

17 Nov. 1967

I gather that preparations are already being made for our homecoming in May. I hope you realise that our time is going to be extremely limited. We hope to divide most of it between you & [my husband’s mother], but also must go to Christchurch for a few days, and also have friends around the country that we hope to visit. So you would do well to reckon on about a week (don’t forget flying time is included in the 28 days). This week will have to include relations too. The plan for an open day or weekend sounds a good one. I had better make it plain from the start that, apart from our immediate brothers & sisters, and possibly grandparents if they are too infirm to travel, we are not going to do any relation-visiting. For one thing, it wouldn’t be fair to the kids, dragging them round from one set of strange faces to another. If you are going to get to know them at all, which from our point of view is the purpose of the visit, we will need a quiet domestic atmosphere with as few strange faces as possible. It took David four months to adjust to living in this country. Also, two days of being an exhibition piece is about as much as T. or I could stand – we are pretty unsociable types!

Here’s where the Yiddish concept of naches comes in. Looking back, I realize now that it mattered deeply to my mother to be able to show us off. She had never seen our children, her first grandchildren, other than in photographs, and she had idealized them. But as a young mother, I was having none of it:

5 Dec. 1967

Glad you see my point about visiting relations, though reading your letter again I have a suspicion that you intend to have them turning up all the time anyway. If this is so, please think again. I know, Mum, you love to have your family about you, and find it hard to understand my attitude. But to me my family is my husband and children, and next, my parents and brothers and sisters. Now I shall be delighted to meet all my uncles and my cousins and my aunts, but since practically all of them are almost total strangers, it would be much easier on us to restrict their visits to a definite two days, and leave us free for the rest of the time to do what we came for, which is to visit you.

In my psychology reading I came across another concept, filial maturity, explained as:

1) By early adulthood, particularly in the 30s, taking on the responsibilities and status of an adult (employment, parenthood, involvement in the community), the child begins to identify with the parent.

2) Eventually, the parent and child relate to each other more like equals.

When I wrote these letters about our forthcoming trip to New Zealand I was 29. After fifty years of being a mother and a grandmother, I now understand why my mother and I were at odds. I’m sorry she had to deal with such a difficult and demanding daughter. I also know this was the way it had to be.

What place have we come to?

I grew up in a country with strict gun control laws. In New Zealand in the 1940s and ‘50s, you needed a permit and a “proper and sufficient purpose” to acquire a firearm, and all weapons had to be licensed and registered. Automatic pistols were outlawed altogether. My dad kept a rifle in a locked closet, taking it out occasionally to go hunting for feral pigs with his friends. But guns were not part of my small town landscape. Even today, New Zealand police officers do not routinely carry firearms.

Imagine my state of mind then, when the newspapers of my newly adopted country ran daily news stories about firearm-related deaths. Looking back now at government statistics, I see that in 1968 the US, with a population of 200.7 million, had about 31,400 firearm deaths. (Since the Center for Disease Control bundled multiple years 1968-1980, this is an average.) CDC, in a 1994 report, predicted that people killed by firearms would by 2003 outnumber vehicle crash-related deaths. Louis Jacobson, in a PunditFact article, verifies Nicholas Kristof’s 2015 statement that “More Americans have died from guns in the United States since 1968 than on battlefields of all the wars in American history.”

On April 4, 1968, our family had been in the US less than a year. My husband Tony was in Washington, DC for an international magnetics conference. On March 30 I wrote to my parents: He is very excited about this, especially as he hopes to meet some of his friends from England who are expected there.

About a week later I wrote again:

10 April 1968

Tony also got involved last week in America’s other big trauma – the race riots following Dr. King’s assassination. He had great difficulty getting out of Washington on Friday [April 5], but fortunately the flight crew of his plane had the same problem, so managed to catch his correct flight a couple of hours late. I gather that the conference was very successful and useful, if somewhat exhausting.

Reading these words again today, I notice the calm, distancing tone. I couldn’t tell my parents that I was terrified. Tony had described to me the view from the night sky: cities in flames all across America.

Two months later, on June 5, 1968, presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy was fatally shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, shortly after winning the California presidential primaries in the 1968 election.

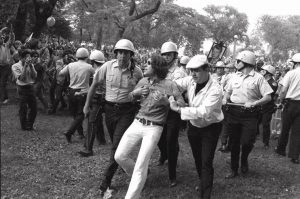

Police lead a demonstrator from Grant Park during demonstrations that disrupted the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in August 1968. (AP) Image from https://www.washingtonpost.com/

Yet more public and political mayhem was to come. In August we endured reports of the violent clashes between police and protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. In its report Rights in Conflict (better known as the Walker Report), the Chicago Study Team that investigated the incident stated that the police response was characterized by:

…unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence on many occasions, particularly at night. That violence was made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat. These included peaceful demonstrators, onlookers, and large numbers of residents who were simply passing through, or happened to live in, the areas where confrontations were occurring.

I have to agree with Haynes Johnson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who was covering the convention. He wrote in a 2013 Smithsonian Magazine story that the convention was

…a lacerating event, a distillation of a year of heartbreak, assassinations, riots and a breakdown in law and order that made it seem as if the country were coming apart.