Archive for December, 2017

The turning of the year

Here we are at the turning of the year. It’s been a hard year in many ways. My particular concern has been the environment and natural resources. I’ve had to witness oil and gas interests take precedence over the protection of fragile landscapes, sacred cultural resources and vulnerable water supplies. Wildfires have devastated Northern California, where I live, including parts of Santa Rosa, the city where we go for many services. A huge fire now threatens Santa Barbara, in southern California, where I lived in the 1970s. Here on the northern coast, warming ocean temperatures have wrought havoc on the kelp forests and the sea creatures that depend on them. Throughout the world, as starving people flee drought-stricken lands, tribal hostilities are increasing.

Meanwhile, the days follow each other. The sun’s arc rises lower and lower in the sky, its rising and setting further and further to the south, and the darkness of longer duration. There will be a pause, a solstice or sun-standing-still, and then a return of the light, and we will celebrate, in our various spiritual traditions, a return of hope.

May you all find hope and joy in the days to come.

The place of art

What is art, and what place has it had in my life? This was the assigned topic for the first set of high school student essays I graded in my first paying job in California. In those days, the late 1960s, California schools had enough money to hire readers to relieve teachers of the time-consuming task of grading papers. I worked primarily with Millicent Rutherford, the Humanities teacher at Lynbrook High School, in the Cupertino Union School District. Over time, we developed a warm friendship.

I was saddened to learn that Millicent died last October, at the age of 91. Her obituary notes: “She will be remembered for her glittering sense of style, her sharp wit, and her boundless energy.” A 1991 Los Angeles Times article on remembering teachers who made a difference includes an anecdote by Stephen Bennett, CEO of AIDS Project Los Angeles:

“We’d study Italian art and [Ms Rutherford] would get . . . photographs from some of the Pompeian paintings that are not typically looked at—the parts of Pompeii they won’t show you because the graphics on the wall are what Americans would consider lewd. And she’d show up in a Pompeian red dress to start the day.”

To honor Millicent’s memory, I’ve been thinking about how I might respond to her essay topic.

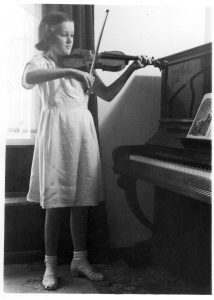

When I was the age of Millicent’s students, music was my passion. I played second violin in my town’s municipal orchestra. At my first concert, the orchestra tackled Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5. It must have sounded decidedly amateurish. But the experience of being a part of that magnificent work, of sharing the language of music with my fellow musicians and with an audience, is a thrill that has always stayed with me.

Tauranga Municipal Orchestra at rehearsal in the high school assembly hall, c. 1952. I am in the front row, just to the left of the podium.

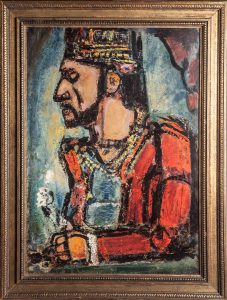

Painting too speaks a language without words. On the wall of my office is a reproduction of Georges Rouault’s “The Old King.” I saw the original fifty years ago, at the National Gallery in London. Friends I had come with moved to another room without me as I sat on a gallery bench, weeping. I still weep inside when I look at it.

Concerts, theatre, dance performances and visits to art galleries have always been a major part of my life. The written word has been my personal art form. To struggle with the lines of a poem, to convey emotional meaning through images, leads me to a personal answer to the question: “What is art?” For me, it is a way of sharing what is meaningful in our lives.