Archive for April, 2018

Liberation by Strobe Light

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

From my battered black metal filing cabinet I retrieve a handful of yellowing sheets, my journal notes from the day I attended my first women’s movement event, a day-long self-discovery workshop sponsored by the Office of Continuing Studies for Women at Foothill Community College in Los Altos Hills, California. Saturday Oct. 14, 1972, all day with lunch, $7.50 reads the opening line, along with a list of workshop leaders.

At the opening forum, my friend Judi and I recognize a few women we know. There is a feeling of bonhomie among the attendees, I have written in my notes. After the introduction we are shown a women’s lib segment from the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family”. Women roar with approval at Gloria’s feminist attitudes, chatter noisily during commercials.

The surroundings for my first breakout session are inauspicious. Out of the rain and into a Foothill College classroom plod two dozen women like myself, suburban housewives, thirtyish to middle-aged, dripping umbrellas. The desks have been pushed back against the cream-colored walls, and the chalkboards are still scribbled with students’ assignments. Self-consciously we obey the call to take off our shoes and sit on the floor. The instructor, in powder blue leotards, is already making pumping movements with her arms.

In formal dancing, she explains, the woman is led by her male partner. But today’s kids dance apart, doing their own thing. We are going to pretend like we are kids. We heave up our sagging muscles. The lights go out. The music comes on, a strong rock beat. A strobe light flickers. I have never seen a strobe before. I am fascinated by the jumping shadows. Impossible to see any other person clearly. The classroom is disappearing, and we are no-place. Though we are crowded together, we are each alone, in our own darkness. At first we copy the movements of the instructor, but imperceptibly private fantasy takes over.

From my mother I learned to fear my sexuality. Now I am doing a sexy dance, gyrating my body in a collage of distant memories. I see again the smoky crush of teenage bodies glimpsed through a basement doorway at a country club near Syracuse, NY. It was 1962; the Twist was just coming in. Terrifying, beautiful, and my fear was mixed with envy of these kids little younger than myself, who could accept their bodies’ needs and express them freely.

My fingers flicker in the strobe light, twenty fingers instead of ten, flying over the keyboard of an imaginary concert grand. I am strong. I am ambitious. I am free. The beat of the music rises to a climax. My body is soaring to a rhythm of its own. I have flown back fourteen years, back to Syracuse, NY, back to the doorway of the smoky basement. I enter the door and mingle with the grease and sweat of the dancers. I am no longer afraid. The tape ends, the lights come on, and we flop exhausted onto the schoolroom floor.

My next workshop is titled “Changing Images.” A large wood-floored room in a gymnasium complex, walled with mirrors at both ends. Again we take our shoes off, and lie on the floor to do a relaxation exercise. “Breathe … out. Now let’s see what happens when we loosen our clothes. Those of us that have belts on, let’s undo them. Let’s unbutton our slacks. There now, isn’t that more comfortable?” We are given a little pep talk on the influence of other people on our fashion choices, then break up into small groups to discuss how we feel about our clothes. I tell about my conservative wool suit, and how mod and worldly and competent I felt when I dressed it up with cream opaque pantyhose and body-shirt to go out and do an interview. A striking single girl confesses that she usually winds up wearing a sexy dress to go to a party where there may be new men. A matron in trim blue slacks and floral shirt tells how she automatically thought of wearing a knit suit to this workshop, until she read in the paper the invitation to wear “comfortable” clothes. She wishes she could find her own style – everything she buys turns out to be too conservative for what she thinks may be the real her, yet very suitable for her role as wife and mother, church-goer, active member of the PTA at her kids’ school. We try on a few wigs and clothes. It’s fun, but inconclusive – there are not enough things to do much with.

I meet Judi at the cafeteria for lunch, and we trade notes. At her clothing workshop, the first of her day, two women had stood conspicuously at the side, refusing to soil their clothes by lying on the floor. Everyone now is very chummy. The cafeteria is crowded. I hadn’t realized there were so many women here. The luncheon speaker gives a brief potted history of the women’s movement. Her voice is rather flat, and I have read it all before anyway. I look at the mural from the morning’s painting session. It is very militant. I look for the positive, affirmative images. Not many. In a flash I know what I want to paint.

My last workshop of the long, full day is a painting session. In theory, we are to paint our reaction to the clip we were shown of the Archie Bunker show “All in the Family,” in which Archie’s wife Gloria expresses feminist attitudes and Archie berates her. But that was early this morning, at the introductory forum. A lot has happened since then.

Most women paint their reactions to the day. One painting is of a huge orange cloud, turbulent, stormy, but beautiful, and raining golden rain onto a green hillside. This was how she saw what was happening today, says the painter. The stirring of new ideas was exciting, but also scary, and in the long run it would benefit humankind.

Many women paint themselves. “This is me when I can’t cope,” writes a mother from a wealthy suburb, whose dark green and black picture shows a figure in bed under the covers, surrounded by black smoke and scary faces. Another draws a bright fire arched over by a brown form. “The brown shape is her man,” says the painter. He is both protecting her from the outside world, and smothering her fire so it can’t get out.

My image comes out fast, so fast I keep running out of paint on my brush. I draw the arms first, in dark, strong red, reaching up, hands wide open. A smiling face, a body, a quick angle of a dress to show that she is female. “Reach out!” I shout in red paint underneath. Then quickly back to the table to find some yellow paint. Bright yellow light scribbles itself behind the figure. She looks too sketchy. Pour the yellow paint into a remnant of blue to give her a green dress. Green hair? Why not? “This is where I am at,” I tell my fellow painters. “I have broken out of my chains.”

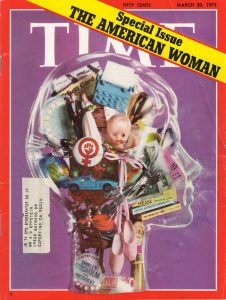

Time Magazine on women, 1972

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

Tucked between two bulging folders in my old black filing cabinet, I find a yellowing treasure: the March 20, 1972 special issue of Time Magazine titled “The American Woman.” Skimming its pages, I’m drawn back to my memories of the early 1970s, when I lived in Cupertino, CA. Oh yes, I think to myself, this is what it was like.

The issue starts, as usual, with letters to the editor. These are from female readers responding to the magazine’s invitation to “write to us about their experiences and attitudes as women, and to tell us how their views on this subject have changed in recent years.” I tabulate the responses. Twenty enthusiastic about the new feminism, three ambivalent, and six tending negative, arguing that, since very few higher level jobs are available to women, by going out to work they “trade the drudgery of housewifery for the drudgery of an office job.” Or, as another writer put it: “Rush out each day to that exhilarating, high-paid position; rush home to that hot-cooked supper (cooked by whom?); relax in that nice clean living room (cleaned by whom?). Most likely, dearie, you’ll hold down two jobs—‘cause when you get home from that executive job in the sky, there ain’t gonna be no unliberated woman left (and certainly no man) to do your grub work.” Sidebars titled “Situation Report” in the various sections of the issue reflect these caveats: prejudice is rampant against allowing women into higher paid or managerial professions.

Time’s editorial attempts to define “the New Feminism” as “… a state of mind that has raised serious questions about the way people live—about their families, homes, child rearing, jobs, governments and the nature of the sexes themselves. Or so it seems now. Some of those who have weathered the torrential fads of the last decade wonder if the New Woman’s movement may not be merely another sociological entertainment that will subside presently.”

Subsequent pages offer a history of the currents of social change that “have converged the make the New Feminism an idea whose time has come.” There are portraits of a range of American women, a piece on “the organizations, aims, difficulties and range of opinions that help make up Women’s Liberation in all its diverse forms,” a one-page snapshot of attitudes in Red Oak, a small Iowa town. Here’s a quote: “Many Red Oak women agree with Doctor’s Wife Jane Smith: ‘A woman’s place is in the home taking care of her children. If a woman gets bored with the housework, there are plenty of organizations she can join.’” A photograph shows Mrs. Smith entertaining friends at bridge. I have a flash of memory: one of my sisters saying the same words to me.

The “Politics” section of the magazine showcases some familiar names: Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, Martha Mitchell, and describes the bipartisan effort of the National Women’s Political Caucus to get more women elected, or selected, as delegates to the Democratic and Republican National Conventions.

The “Science” section describes the difficulties a woman astronomer faced. As a woman Margaret Burbidge, who helped develop a new explanation of how elements are formed in the stars, “found that she could get precious observing time at Mount Wilson Observatory only if her husband [a physicist] applied for it and she pretended to act as his assistant.” The Burbidges also ran into nepotism rules at the University of Chicago. “’The irony of such rules,’ says Mrs. Burbidge, who had to settled for an unsalaried appointment while her husband was named a fully paid associate professor, ‘is that they are always used against the wife.’” I think of women scientists I have known who suffered the same exclusion, such as Beatrice Tinsley, a British-born New Zealand astronomer and cosmologist whose research made fundamental contributions to the astronomical understanding of how galaxies evolve, grow and die. Beatrice had to divorce her husband, a Texas University professor, and move to Yale to gain the position she needed to do her work.

In many science fields, recognition for outstanding women is still abysmally low. I think of efforts by my son David, a mathematician, to redress the paucity of profiles of eminent women mathematicians in Wikipedia.

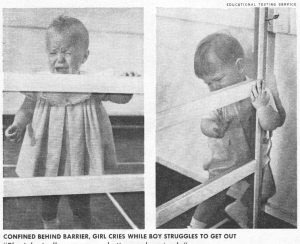

Section after section, the stories continue. “The Press” section is subtitled “Fight from Fluff,” how women’s pages are shifting to more general interest features. ”Modern Living” talks about efforts to find new pronouns, the opening of day care centers, and changes in marriage dynamics. The Situation Report for the “Law” section puts the number of women lawyers in the U.S. at 9000, 2.8% of the total number of lawyers. Of this small number, “less than 12% of them were making more than $20,000, as compared to 50% of the men.” Similarly depressing are statistics for recognition of women in the arts, in business, and in medicine. The “Behavior” section, which looks at research into sex-related differences in early childhood, seems to reinforce stereotypes: “Many researchers have found greater dependence and docility in very young girls, greater autonomy and activity in boys.” The accompanying pictures show two babies behind a barrier set up to separate them from their mothers. The little girl cries helplessly; the boy struggles to get out.

A keynote essay by Sue Kaufman, author of the novel Diary of a Mad Housewife, attempts to capture the feelings of a composite American woman, interested in the new ideas, admiring of feminist leaders, but cautious about jumping on the bandwagon. Kaufman describes an imagined scene: an admired leader is coming to town to speak. The woman arranges for a babysitter. “She will go, usually with friends. They will arrive … take their seats—and slowly it will begin to happen … she begins to feel the flickers and currents of a mass communion, a rising sense of excitement that she imagines parallels what one feels at a revival meeting … this powerful thing happening, this sweeping, surging, gathering-up-momentum feeling of intense camaraderie, solidarity movement.” After the meeting is over, Kaufman describes the woman driving home, paying the sitter, returning to the children and the kitchen “to take up the reins of her existence. Only—something is wrong. She is overwhelmed by a terrible sense of wrongness, of jarring inconsistency. There was that surging, powerful feeling in the hall, and now, stranded on the linoleum under the battery of fluorescent kitchen lights, there is this terrible sense of isolation, of walls closing in, of being trapped. …but she doesn’t burst into tears. …In spite of the desolation she feels, she knows that she is not alone…there is enormous comfort in knowing that. And knowing that is one of the big changes in her life.”