Red is the color of lost empire

In the 1940s, when I was a schoolchild in New Zealand, we used our red pencils to color in maps of the world. Great Britain, of course: England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (Eire was gone by then). Huge chunks of the African continent that still had their old names and boundaries: Sudan, Gold Coast, Cameroons, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Rhodesia, South Africa are just some I remember. The Indian subcontinent with neighboring Ceylon and Burma. Pieces of the East Indies archipelago. Australia, our nearest neighbor. Little red dots, lots of them, for Pacific island dependencies. The big swathe of Canada. More dots in the Caribbean, and a dab for British Guiana on the South American mainland. We pressed our red pencils hardest for New Zealand, the furthest outpost of the British Empire, on which, it was said, the sun never set.

This website has a fascinating time lapse view of

the rise and fall of the British Empire.

Even as we children beamed with pride at our splendid red maps, our world was changing. By the time I moved to England in 1962, the political geography I knew as a child was obsolete. The British had retreated from the Indian Empire, leaving behind a land painfully divided between Hindu and Moslem. The red chunks of Africa rearranged themselves into separate nations. South Africa, Canada, Australia and New Zealand declared themselves a Commonwealth, still recognizing the Queen, but independent of British rule.

Old loyalties die hard. The Union Jack still fills the top left corner of the New Zealand flag. In 1962, New Zealanders still looked to England as the “mother country” and I could write to my parents, in my first letter from London: “[W]e have finally arrived in the Heart of the Empire.”

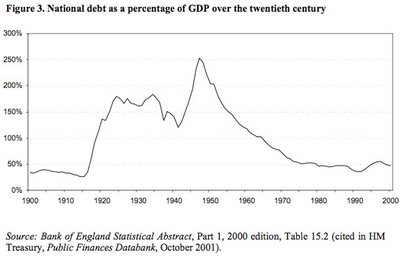

The mood I encountered in the old empire’s capital was bleak. Great Britain had survived World War II, but at an enormous financial cost, and the national debt hung like a shadow over the economy.

After the austerity of the 1950s, living standards were improving, but the country’s wealth, prestige and authority had been severely reduced. Economically, Britain was slipping behind its competitors. Relations between management and labor were bad; the newspapers were full of reports of strikes and unrest. It did not feel like a good place to be starting a new adventure.

Love of Place

This week I learned a new word, soliphilia, which means love of place. I’m inviting you to read a beautiful essay about place by my friend Sharman Apt Russell, who lives near the Gila National Forest in New Mexico. She starts:

I walk out of my house onto a country road. If I go north two miles, I’ll be in the Gila National Forest, 3 million acres of pure New Mexico: ponderosa pine, pinon pine, scrub oak, juniper, yucca, prickly pear. The names of familiar species are like the beads on a rosary: mountain lion, black bear, javelina, coati. If I walk south five miles, I can turn onto Highway 180 and find my way to anywhere, Dallas or Paris or Bangkok. By God (and here comes my first imitation of Walt Whitman) I live in the best of places!

Click here to read on, and enjoy her lovely pictures.

Discovering the familiar

When I first went to London, I already knew it, or thought I did. The literature I studied growing up was English literature – novels by writers who lived in England and wrote about English life. From them I learned to find my way around London in my imagination. When I finally walked the London streets in 1962, I recognized names every time I glanced at a signpost. From Dickens I’d learned about the Inns of Court and Chancery Lane. I knew that Savile Row was filled with bespoke tailors, though I had only a vague idea what “bespoke” meant. Bond Street was where expensive jewelry was purchased by upper crust people who visited expensive doctors on Wimpole Street. Carnaby Street was where fashionable young people bought the latest fashions. As a newspaper reporter, I revered Fleet Street, where the great London dailies were headquartered.

The BBC world news, which in New Zealand we listened to on the radio every day, opened with the chimes of Big Ben, the clock at the Palace of Westminster, where the British Parliament met. I knew the sound, but still could write in amazement to my parents: When Big Ben strikes the whole street reverberates.

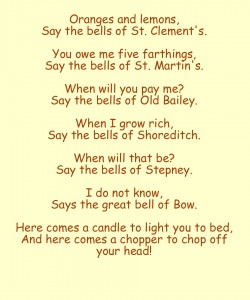

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

A big thrill was hearing the bells of St. Clement Danes in the Strand sing “Oranges & Lemons” as we strolled past for the first time. Back came the singing game we played as children, racing through an arch made by two of our playmates, trying not to get caught.

Here’s a Wikipedia page that includes a recording of the St. Clement Danes bells.

I wrote in my notes:

[V]ery difficult not to associate names of places in London with famous songs about them – find myself starting to hum the songs as I read the names.

We went to Buckingham Palace, of course, and I thought of my childhood book-friend Christopher Robin:

They’re changing guard at Buckingham Palace –

Christopher Robin went down with Alice.

Alice is marrying one of the guard.

“A soldier’s life is terrible hard,”

Says Alice.

My memory of those first few days in London is a sense of wonder and excitement as places became real. At the same time, there was a disconnect. I had to let go of expectations that special buildings, Sir Christopher Wren’s St. Paul’s, for instance, were set off from other buildings, up on a pedestal, giving off a radiant glow. Reality was grimy walls and a crushed cigarette packet in the gutter. I wrote:

Peculiar sensation frequently of almost having been here before – not the usual one, connected with place, but connected with names – so familiar, and the outlines themselves so familiar, except that until now we had not known how they stood in the context of the rest of the city. –so this is Big Ben – so this is St. Paul’s – and we know they are, we have always known them, but we did not know that we would find them just here, with this office building on this side, and that park or square on the other. To walk down to the Embankment, and just happen to come upon Cleopatra’s Needle, standing so casually by the river. Somehow I had expected the great tourist attractions to be set apart, and gazed at always in awe. It is a jolt to realise that millions of people live and work alongside them every day of their lives, and take them so much for granted that they hardly see them. They leave the gawking to the tourists, who pour in by the busload, scatter their trash, and depart. The permanent thing is the life that goes on all around these not so very sacred objects, and of which they form a part.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Navigating the spider web

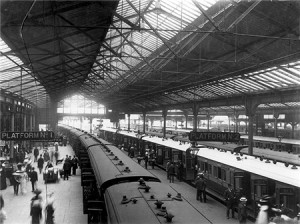

When Tony and I finally arrived in London after our weeks-long journey, our college friends Bill Moore and Robert Ludbrook met us at Waterloo Station. I felt like hugging them both, but thought they might be embarrassed, I wrote in my notes. New Zealand men of our time did not go in for overt displays of emotion.

An early 20th century view of Waterloo Station. It looked much the same in 1962. Image from http://www.heritage-explorer.co.uk/

Robert spoke of his and his wife Miriam’s “traumatic experience” when they arrived. They sat for three hours in the huge Waterloo station, not knowing whether they were on the right platform, not sure what to do, or even if they could get to Derby, in the middle of the country, where Miriam’s parents lived. Their ten-month-old baby was crying from hunger – none of them had eaten for three hours. They knew no-one in the city. “I decided then that no-one I called my friend should suffer the same fate,” Robert said.

Waterloo Station is part of a transportation network that on a map looks like a giant spider web with the heart of London at its center.

The trains link to London’s famous Underground system, with which I became very familiar in the next few weeks as I searched for short-term accommodation while Tony job-hunted. I found these notes in my black filing cabinet:

Several days [after our arrival] I returned to Waterloo, and could not remember ever having seen the concourse of the station before, yet we must have passed through it on our way to the underground platform. I can remember the way the train came into the main platform – rows of long platforms jutting out into the track, with the entrance at the head of them, and the high wrought iron and glass ceiling, very dirty, overhead.

And I can remember standing on the underground platform, although that memory rapidly becomes confused with standing on other underground platforms, all confusingly similar. Always the same smell, compounded of dust and disinfectant and human bodies, always the same roar of the escalators, the same draughts of air rushing in or out, and the airless feeling when a train has passed, the rattle and screech of the trains grating on the ear-drum and jangling the nerves. The hypnotic movement, grinding to a halt at stations, and the doors swishing open. Some go in and some go out, but they are always the same people.

It is very easy to miss your own station if you do not concentrate very hard. The signs are easy to follow – in the station itself you do not get lost unless you are very blasé and think you know where you are going – but all the stations appear exactly the same – it is just that in each the maze of tunnels is different. But once on the right train you feel that you are safe, that you can relax for a while from the struggle of finding your way about. This is the most dangerous of all, as before you know what has happened, the train will have swished past your station while you were still dreaming.

Stereotypes and misconceptions

When I lived in England in the 1960s it bugged me that, when they learned where I was from, people would typically have one of three responses:

1) They had no idea where New Zealand was.

2) They thought it was part of Australia.

3) They knew of it as that pastoral paradise they’d dreamed of emigrating to when they were younger.

Reading my old notes about coming to England in 1962, I realize that I too had huge misconceptions about what my new home would be like. Here is the account of our arrival:

First view of England – not counting faint views through the foggy channel – picturesque houses of Isle of Wight – only we thought it was Southampton and decided England must be charmingly antique and folksy, with church spires peeping through the trees and glowing green fields running down to the sea. but we were a little perturbed that we couldn’t get our geography right. Fascinated by the light – very soft, still a little hazy after the rain and fog of the day before, but with the sun coming through in pale golden streaks.

Our ship anchored off the Isle of Wight and passengers were sent ashore by tender. We managed to miss the boat train by being held up at Customs – a fuss over a lens Tony had bought in New York. But were well looked after by the railway porters, who rushed to get us into a taxi to catch the same train at the central station. On the way, the taxi-driver casually pointed out the old Roman wall of the town. As we gazed in amazement at something 2000 years old, and taken for granted, we began to realize the sense of history about the place, which confirmed even more the feeling of newness about New Zealand. My notes continue:

As the train pulled out of the centre of Southampton we discovered the slums. Obviously not the worst of the slums, but up till then we haven’t really believed that they existed, although we could mention them matter-of-factly. England from New Zealand looked a golden land, a land of opportunities, a land that housed the rich heritage of the old world. It definitely did not mean rows and rows of dreary brick buildings exactly alike, and behind them rows and rows of exactly similar yards, with blackened paling fences and rubbish tins. But occasionally we recognised the cry of a human spirit – from among the debris would rise a patch of golden daffodils dancing in the pale sun, cultivated by loving hands. And for a time we passed through farmland, with pussy-willow growing fat by the railway track, and small boys ambling cheerfully by hedges. Even one or two thatched cottages and barns, and we felt with a sentimental rush that we really were in England. But as we neared London the houses grew thicker and more dreary, their bricks blackened with smoke and soot, their monotony more grey. But even here people were making the best of their situation with window boxes full of bright flowers.

As well as misconceptions, I had opinions. I was amused to find in my notes that, with no knowledge of English social attitudes and no background whatsoever in urban planning, I laid out an argument about high density housing:

I have not yet resolved the problem of what is the best form of high density housing for such a city. Most people are housed in these old row houses, a monotonous block, but at least with some little bit of ground, however filthy and untidy, that they can call their own. The other alternative seems to be tall apartment blocks in their own parks. The disadvantage of these seems to be that the people shifted into them lose their sense of community – they no longer feel that their home is their castle, for they share it and its services with dozens of other families. I would feel the lack of a bit of ground of my own to cultivate, or just sit in. A semi-public park is all very well, but it gives no opportunity for creative contact with the earth. I have seen a few modern blocks of row houses, some of which are quite pleasant, but others will obviously become the future counterparts of the present monstrosities – pleasing to look at now because they are new, but once the newness has worn off little of artistic value will remain. Others, particularly a small block seen near Primrose Hill, had a cheerful friendly atmosphere that appeared more durable.

Ah, the certitude of youth.

The Rain in Spain and all that

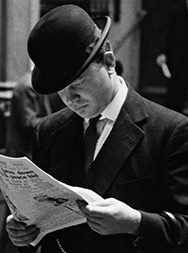

In April 1962, fresh off the boat from New Zealand, I stood on a railway platform in Southampton, on England’s south coast. All around me the sound of voices, English voices. In notes written a few days later, and saved in my old black filing cabinet, I wrote:

Railway platform – probably much the same as those in NZ, but had a sense of Englishness about it – hard to define, but probably due to the language spoken – correct English accents as if they were the most normal thing – this takes a bit of getting used to. … Here on the Southampton platform we heard the ‘jolly hockey sticks’ manner of speech for the first time. In all cases, it is difficult to distinguish in the mind between the real thing and the caricature which up to now is all we have known. The same with men in bowler hats and umbrellas.

Reading these notes fifty-three years later, I see in them the ambivalences and ambiguities that filled my formative years. Europeans had been in New Zealand for scarcely a hundred years. From the industrial ferment of 19th century Britain, the English, Irish and Scots immigrants brought a legacy of radical socialism, and from the obduracy of the land they grew a people that glorified the strong men, the rough, the plain-spoken, and left to its women the care of the arts and the domestic hearth. For my father and his friends, a man was considered useless unless he was good at working with his hands. An Englishman, especially if he had a “posh” accent, was teased about being a “Pom” and eyed with suspicion until he could prove himself as one of the blokes.

On the other hand, well-spoken Englishwomen dominated the social life of the resort town where I grew up. English bone china teacups clinked in parlors where pictures of thatched cottages might grace the walls, and genteel conversation was made about making the trip “Home” to the old country.

Prejudices about accent can cut both ways. The longer I stayed in England, the more I realized that how one speaks was critically important in that class-bound society. I quickly dropped all the Kiwi slang I ever knew. But, unlike Eliza Doolittle in “My Fair Lady,” I could not get my tongue around the inflections and tonalities that signified “proper” English. My accent slotted me into a pigeonhole labeled Colonial, from which I could escape only by leaving.

Westernesse in the rain

An Aran Island scene on a sunnier day. This aerial photograph by Aongus O’ Flaherty is from http://www.aerarannislands.ie

My first glimpse of the British Isles was the Aran Islands, at the mouth of Galway Bay, where our trans-Atlantic ship stood off to land a few passengers. It was an emotional moment. The destination of our long sea journey at last become visible. Vague romantic dreams faced with reality. I was shocked by the bareness and bleakness of the landscape. Heavy rain was falling, and wind lashed waves onto the shore. The bare rock of the grayish white hills (karst limestone, I later learned) was dotted with tiny scraps of green that glowed brightly in the rain-sodden air. A few white cottages of plain design: four walls and a pitched roof, a door in the middle and small windows at each side.

In notes written at the time, I tried to capture my sense of the place:

Centuries old, yet timeless. Feeling of age and solidity of a way of life that has gone on for centuries – the grimness of it, the few rewards. Can imagine the people to be tough and dour. Weather-beaten faces of seamen who brought the tender out to pick up passengers. No-nonsense faces, with a wry sense of humour.

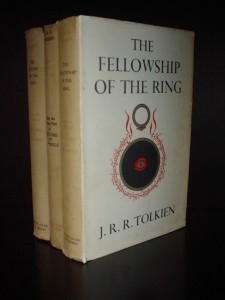

The Lord of the Rings trilogy in its original format as published by George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. in the mid-1950s.

From halfway across the world, the reality of the British Isles was also mixed with romantic fantasy. Before we left New Zealand, copies of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, with the device on its cover of Sauron’s eye within the Ring, surrounded by Elvish script, were passing from hand to hand among our friends. As I looked across the sea to this westernmost part of Ireland, I couldn’t help thinking of Tolkien’s Westernesse, the place to which the fairy people set out when life on Middle Earth became impossible for them.

The curtain of rain swept down again. The ship moved on, headed for Southampton, the end of our journey and the beginning of our new life.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Doomed romance on the high seas

Observing one’s fellow passengers is a major pastime on board a ship crossing the Atlantic, especially for someone with dreams of making her name as a writer. Among the yellowing notes in my old black filing cabinet I found a brief sketch of a man who shared our dining table when Tony and I crossed from New York to Southampton in April 1962.

Gerry was a young American playwright off to Dublin to try his luck on the Irish stage. He told us he lived in a shack on Santa Monica beach, where his wife supported him while he wrote plays. The plays had been performed by amateur groups, but not professionally. He has left the wife in the shack on the beach with her dog for company, while he tries find work in Dublin – anything to do with theatre – stage hand, etc. I wrote:

Tall, lean, dark-haired, glasses, rather dreamy abstracted look, well-cut clothes. Gives the impression that his plays are about the grave problems of the world, though he never spoke of their content. Did not appear to be very interested in the people around him – hardly noticed most of them – except a blonde who had engaged the deck chair next to his. Tall, well-built girl, clear-cut features, thick mane of soft fair hair piled seemingly carelessly on top of her head. Poise and assurance. Swiss. Appeared to laugh at his moonstruck attitudes. He came when she commanded to the bar with her, and sat until far into the night. But on the last night, she refused to come to the empty chair at our table to join him in coffee and liqueurs – pleaded another engagement. So he had a liqueur brought to her at her table. Conspicuous mark of favour, as no-one else at that table was drinking liqueurs. Gerry utterly miserable until he left the ship – followed her with his eyes like a dog, and spent as much time as possible with her. She tolerated this, but obviously not as heart-broken as he.

My writer instincts set me to imagining the wife and creating motivations for Gerry and the blonde woman:

Can infer probably wife G. left at home was too devoted, believing too much in his great abilities. Probably small and neat, shiny dark hair, possibly cut short, light blue eyes. Quite happy to provide material needs so that he can have peace to get on with his writing. Likes to discuss his plays with him as he writes, but believes everything he does is so good that she is unable to provide stimulus by disagreeing with him.

By contrast, the blonde doesn’t give a damn about him, is contemptuous of his writing ability, but still allows him to flatter his ego a little by accepting attentions from him. G. confused in his own mind. Talks a great deal about his wife – not about what she is like, but her abilities at cooking, etc. – providing him with comfort, pampering him, giving him the security that a child needs, and that he is now missing. At the same time tormented by the physical attractiveness of the blonde, and by her superiority to him, not only assumed by her, but actually so: she is more sure of her place in the world. He finds her indifference to his art stimulating and at the same time humiliating; he believes very seriously in his art, but as yet has nothing to prove it to himself or others – no success as a practical yardstick. Believes he can see new horizons of human experience opening for him in the duality of his relationship to her, excited by the effect this will have on his art, though as yet it does not occur to him how he will put this into words, and is more attracted to her because of this.

Most of his actions a form of posing, related to his belief in himself as an artist, e.g., self-conscious staying up drinking far into the night, arriving half an hour late for meals, with the obvious inference that he has been too lost in his art to notice the time, or else too busy drinking his life away at the bar – those around are expected to take the explanation that appears to them the most romantic.

I don’t know how the rest of Gerry’s life turned out. Googling his name turned up no clues. All that remains is this little story of a doomed shipboard romance and a young man with a dream.

Music of the Elysian Fields

Growing up in New Zealand, the Metropolitan Opera House in New York was the stuff of dreams: the tragic drama of the opera plots, the names of the great stars, the LP disks in my mother’s collection played over and over. To actually be there was an extraordinary sensation. “The whole place just breathes atmosphere,” I wrote to my parents, “the opulent decorations of a former era, and the shades of the singers who rose to fame on its stage – portraits of the greatest everywhere. “

Thursday, March 29, 1962 was our last night in New York before my husband Tony and I took ship for England to continue our youthful adventures. My sister Evelyn treated us to the opera tickets as a grand finale to our visit with her. The performance that evening was Gluck’s “Orfeo ed Euridice,” a very quiet, 18th century version of the story, with a happy ending. To quote from the Metropolitan Opera synopsis:

“Overcome with grief and remorse, the poet cries that life has no meaning for him without Euridice (“Che farò senza Euridice?”). Preparing to take his own life, he resolves to join his wife in death. Before he can do so Amor appears and announces that Orfeo has passed the tests of faith and constancy and restores Euridice to life. The happy couple returns to the upper world, where they are greeted by friends, who perform dances of celebration. Orfeo, Amor and Euridice praise the power of love.”

What stays in my memory is the dancing. As I wrote to my parents: “The ballets, particularly in the scene in the Elysian Fields, are really beautiful. I think it is the ballets that really make the opera – the terrific contrast between this scene and the previous one – the Furies at the entrance to Hades – all dressed in torn black tights, writhing and twisting, outlined against eerie red flames.”

Here is a YouTube recording of Gluck’s Elysian Fields ballet music.

If you’d like to learn more about the performers, here is a page from Opera News, March 10, 1962

I also found this March 1962 review by Irving Kolodin in the Saturday Review:

“On the whole, the visual aspects of this ‘Orfeo’ were more absorbing than the aural, for Harry Homer’s settings (of 1938) still provide an atmospheric frame for the action and Violette Verdy (a replacement for the absent Alicia Markova) is an excellent dancer, as is Arthur Mitchell, who shared the place of prominence with her. John Taras designed the choreography, which was theatrically justifying if somewhat showy, in its lifts and leaps, for the repose of the Elysian Fields.”

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Cycles of life

This week’s post is reprinted from the Arts & Entertainment section of the May 29 Palo Alto Weekly. Henri and I are very excited about our upcoming reading.

Cycles of life

Two poets return to Palo Alto for shared reading

by Elizabeth Schwyzer / Palo Alto Weekly

Poets and friends Henri Bensussen, left, and Maureen Eppstein will read their work in Palo Alto on Friday, June 5, at Waverley Writers. Photo by Tony Eppstein.

“My friend’s body is a brown leaf,” writes Maureen Eppstein in “Going Dark,” a poem from her recent chapbook, “Earthward.”

” … the fierce flame of her will/refuses surrender./ It’s not death’s darkness she resists/but the loss of a self transfixed/by what is beautiful.”

That same enthrallment with life she witnesses in her dying friend is evident throughout Eppstein’s collection of 26 poems. Beguilingly simple, founded in close observations of nature, these poems unfurl to reveal the writer’s keen sensitivity, sense of humor and clear acknowledgment that every life ends with death.

On Friday, June 5, the former Palo Alto resident and Stanford University employee will return to town to read from her new collection. She’ll be joined by fellow poet Henri Bensussen, also formerly of Stanford. Both longtime attendees of Palo Alto’s hallowed Waverley Writers — a free, monthly poetry reading founded in 1981 — Eppstein and Bensussen separately retired to Mendocino County, where they’re each active in the writing community. Their Palo Alto visit marks more than 15 years since their departures — Bensussen and her partner left the region in 1999, Eppstein and her husband in 2000 — yet both are well-remembered by area poets.

Janice Dabney, who shared a writing group with Bensussen and Eppstein and worked alongside Eppstein both on the Waverley Writers Steering Committee and at Stanford, spoke of both writers as “very good people” and recalled not just Eppstein’s poetry but also her humanity.

“She was very supportive of me being a gay person,” Dabney recalled. “She made a point of putting her money where her mouth is, which is a good summary of Maureen: She’s not a person who sits idle and spouts philosophies; she gets out there and acts and makes the world a better place.”

Those on the Mendocino Coast speak in equally glowing terms about both women and their work. Norma Watkins, secretary of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference and creative-writing instructor at Mendocino College Fort Bragg campus, explained of Bensussen, “Henri was my student in the past and writes this delightfully quirky prose and poetry. She has a very odd and wonderful imagination so that when you begin reading one of her poems, you never know where it’s going to go.”

Director of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference, Karen Lewis, said of Eppstein, “You can tell from her work that she has a daily, connected presence in nature. Her nature metaphors are especially remarkable.”

Lewis also described a new project of Eppstein’s: a collection of short essays based on her youth in New Zealand and her immigration to the United Kingdom. Those essays can be found at maureen-eppstein.com.

Bensussen, too, mines her own past for material. In “Chimney Rock,” a poem from her new and first chapbook, “Earning Colors,” birds of prey serve as metaphors for partnership and a departure point for a meditation on separation and divorce:

“Peregrine falcons nest in a hollow/under the cliff’s rim. They mate/for life, unlike us or elephant seals.”

Later, she shows herself, standing alone as birds swoop overhead:

“Vultures hunt the dead, veer close/when they notice me. I stare them off. Pose — /Still Life: Woman in Love, Once.”

Both Bensussen’s “Earning Colors” and Eppstein’s “Earthward” are published by Finishing Line Press, a small publisher based in Georgetown, Kentucky. Bensussen explained that she entered the manuscript in a poetry contest with Finishing Line, and though she did not win, they offered to publish the chapbook anyway.

As for the collection’s title, “When you send in a poetry manuscript, it has to have a thread or theme,” she explained. “I realized I had quite a number of poems centered around the idea of color.”

Like Eppstein, Bensussen has a deep connection to nature, one fostered by her studies in biology and many years of birding and gardening. Upon moving to Mendocino, she explained, “I became immersed in the natural history of the area, and also fascinated by how people interact. Often, someone says something and it sends me off on a poetic journey.”

“Earning Colors” is full of evidence of such journeys. Friends’ stories and strangers’ cast-off comments pepper the collection, giving the sense of a writer moving through a crowded room, picking up on snippets of conversation. In “Blood Test,” it’s an “overly friendly” nurse whose question about the origins of Bensussen’s name sends the writer into reflections on “disruptive history,/as tubes fill with dark pulses of my life.”

Life and death draw close in both Bensussen and Eppstein’s work.

“Earthward,” Eppstein’s third poetry chapbook, is “really about the cycles of life and death,” she explained. “It’s centered around the poem ‘Going Dark,’ which was written for a friend in New Zealand as a memorial. She suffered from multiple sclerosis for 40 years, gradually losing more and more of her use of her limbs. Toward the end of her life, we would have conversations about how she was afraid of losing the self that could be moved.”

The self that can be moved is on full display throughout “Earthward,” and the scenes that move the poet are often those drawn from nature. In “Osprey with Fish,” Eppstein writes with simple power of three lives: the bird, the fish and the woman who watches their flight:

Undercarriage of leg and talon

joins two bodies similar

in sleekness,

twinned

as life and death conjoin

in a continuum

of nourishment.

Huge wings slow over forest,

a fading cry.

“Earning Colors” and “Earthward” are available at Books Inc., Town & Country Village, Palo Alto, and online at finishinglinepress.com.

What: A reading by poets Maureen Eppstein and Henri Bensussen

Where: Waverley Writers, Palo Alto Friends Meeting House, 957 Colorado Ave.

When: Friday, June 5, 7:30 p.m.

Cost: Free

Info: Go to tinyurl.com/l4lvwgh or call ![]() 650-424-9877.

650-424-9877.