The Language of Plants

Have you ever wondered whether trees talk to each other about what’s going on in the forest? Can they show compassion or motherly love? Do they team up to ward off an attack?

Recent research has shown that plants communicate using an electrochemical “language.” Taking a break from exploring my old black filing cabinet, I’d like to share a poem about this discovery. It’s from my new collection, Earthward, available from Finishing Line Press.

The Language of Plants

We who move about are at a loss.

We do not know what words to use

for speech that has no metaphor

in the human tongue.

We have ways to speak of learning,

words for memory, decision-making words.

We speak of synapses of neurons in our brains,

name the organs that receive our senses—

ears, eyes and noses, taste buds, fingertips—

words all based on human forms.

The standing-still ones

message their pheromones into the air:

Aphid invasion. Deploy toxin defenses.

Send for the predator wasp to counter-attack.

Roots zing with electrochemical charge

as through their internet—

a mycorrhizal tangle of yellow threads—

they share resources with their kin,

and even with neighbors of other ilk:

Fir borrows summer sugar from birch,

pays it back in the time of barren twigs.

We need new definitions to embrace

the beings who feed on light

not in some alien galaxy

but close at hand:

Does intelligence mean to have a brain

or problem-solve?

New ways of standing in a bean patch

or a forest grove

in awe and wild surmise at all

this human brain can not yet comprehend.

A Kiwi at the Top

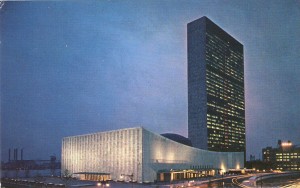

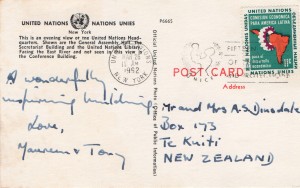

It felt like being in a fairytale. There I was, a country bumpkin on the 37th floor of the United Nations Building in New York, interviewing a man second only to Secretary-General U Thant himself.

When I left my job at The Press, Christchurch’s morning newspaper, to go abroad in 1962, the paper’s editor handed me a list of names. “These are New Zealanders who have done something interesting with their lives. Track them down and send me back some interviews,” he said.

On the list was Bruce Turner, Controller of the UN Secretariat. In a letter to parents, I described him as “A typical Kiwi c haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

haracter, in spite of the smooth polish of diplomacy. Very shrewd, and a hard-case sense of humour. We waited in his beautifully appointed office on the 37th floor while he concluded an urgent meeting on the Congo, and even while we were there, there were at least 10 interruptions – news coming in all the time of countries deciding to buy bonds to support the Congo operations, missions to authorise and statements to sign. He has control of all the financial side of U.N. – which in effect means the whole show. Meanwhile we joked about where in N.Z. he would retire – decided on Tauranga [my home town] because it was near his friend in Hamilton who owned a brewery.”

Here’s a transcript of the interview.

1962 Bruce Turner interview

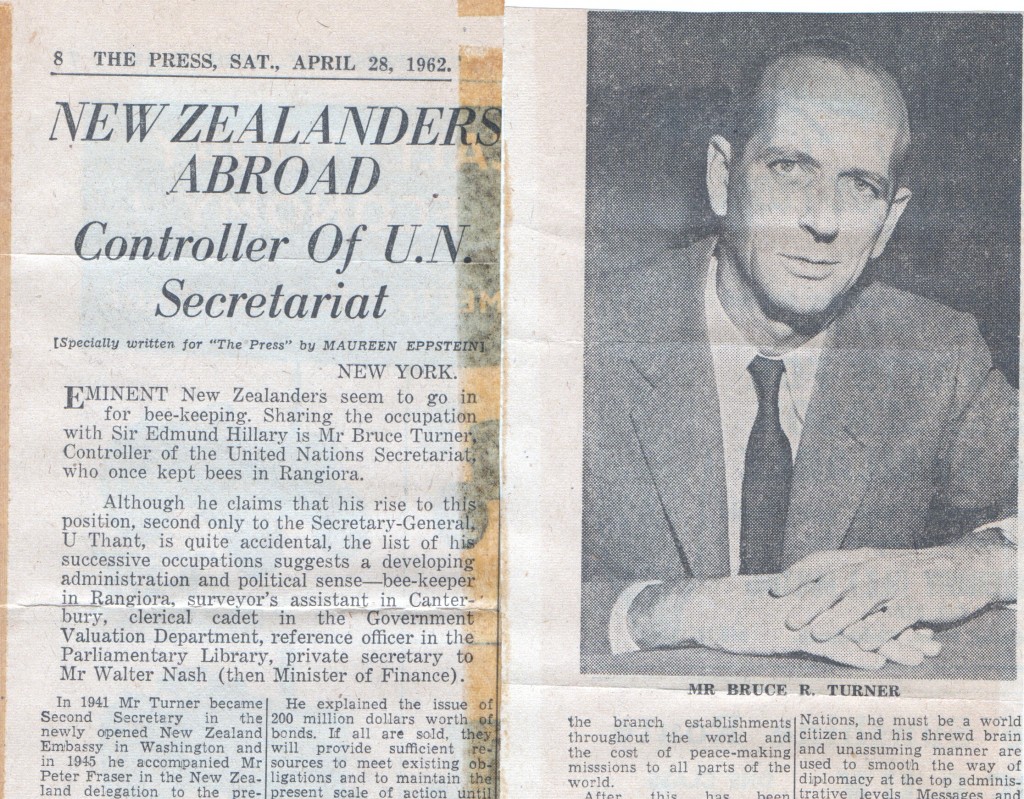

Eminent New Zealanders seem to go in for bee-keeping. Sharing the occupation with Sir Edmund Hillary is Mr Bruce Turner, Controller of the United Nations Secretariat, who once kept bees in Rangiora.

Although he claims that his rise to the position, second only to the Secretary General, U Thant, is quite accidental, the list of his successive occupations suggests a developing administrative and political sense—bee-keeper in Rangiora, surveyor’s assistant in Canterbury, clerical cadet in the Government Valuation Department, reference officer in the Parliamentary Library, private secretary to Mr Walter Nash (then Minister of Finance).

In 1941 Mr Turner became Second Secretary in the newly opened New Zealand Embassy in Washington and in 1945 he accompanied Mr Peter Fraser [the NZ Prime Minister] in the New Zealand delegation to the preparatory commission on the first session of the new United Nations.

“Here Mr Fraser had the misguided generosity to lend my services to the first Secretary-General, Trygvie Lie, and I haven’t been able to get out of it ever since,” Mr Turner said recently in New York.

Vast Responsibility

On him rests the responsibility for all financial aspects of the organisation’s activities. “And since everything we do involves money, this means, in effect, the whole lot. The position would be comparable in New Zealand to that of the Treasury, the Auditor-General and in some respects the Public Service Commission, all rolled into one. Sometimes I suspect that I don’t know entirely what the job involves myself,” he said.

His department prepares in advance a budget of regular expenditure. This includes the administration of the secretariat in New York and the branch establishments throughout the world and the cost of peace-making missions to all parts of the world.

After this has been approved by the Administration and Budgetary Committee of the General Assembly, commonly known as the Fifth Committee, the money is collected on a quota system, based on the capacity of each member government of the United Nations to pay. This quota is periodically revised by a committee of ten experts.

But for extraordinary expenditures, such as the United Nations Emergency Force sent to the Middle East in November 1956 and the force sent to the Congo in July, 1960, a separate budget is required, although the proportion borne by each country remains the same.

A Major Problem

Here lies one of Mr Turner’s biggest headaches. Certain countries claim that they have no legal liability for their quota of this extraordinary budget. Meanwhile, funds are running low, but the need for maintaining forces in the Congo continues.

He explained the issue of 200 million dollars worth of bonds. If all are sold, they will provide sufficient resources to meet existing obligations and to maintain the present scale of action until the end of 1963.

Mr Turner put the problem in the smoothly rounded language of diplomacy and press statements: “On the success of this bond issue depends the future of the whole organisation and its peace-keeping operations.” He broke off to joke grimly: “Oh well, if it fails, this place will be blown up and I will be out of a job.”

He spread his hands lightly round the pleasant wood-panelled room with its quiet beige and jade upholstery. Heavy curtains hid a view of the East River and Brooklyn in the early evening. On a low table, beside a bowl of spring flowers, a handsome Maori carving gave a hint of the occupant’s country of origin.

“Some day I might retire to New Zealand—that would be the normal procedure for any expatriate New Zealanders,” he said. “It would be somewhere with a warm, mild climate. Tauranga perhaps—that is not too far from my friend in Hamilton who owns a brewery.”

Meanwhile, like all other employees of the United Nations, he must be a world citizen and his shrewd brain and unassuming manner are used to smooth the way of diplomacy at the top administrative levels. Messages and telephone calls continued to pour into his office, telling of Government decisions on the bond issue. The maintenance of forces in the Congo, while still a grave problem, seemed a little more hopeful.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Art stuns like a hammer blow

With gold velvet drapery as backdrop, the newly acquired Rembrandt, “Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer,” stood on an easel in the foyer of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. Spotlights accentuated the golden glow of the painting’s surface. As I gazed, I felt a resonance with the feelings of the person depicted, my thoughts drawn into his as if into a dizzying vortex. I was astounded that brushstrokes and pigment could have such power to move me.

I had not seen great art before, except in books of reproductions. I had devoured the collection of large format books in my high school art room, and spent hours browsing the art section of secondhand book shops when I was in college. When we left New Zealand in 1962, Tony and I had as a priority to visit art museums and see the work of artists we admired. But nothing had prepared us for being in the presence of the real thing. Upstairs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art we found a whole room of Rembrandts. Dancing down a broad staircase, a whole series of bronze sculptures by Edgar Degas. We saw so many great works we discovered the phenomenon we named “mental indigestion” and wished we had more time in the city so that we could come back. We knew it would take weeks, months even, to absorb all this museum had to offer.

We visited other art museums during this stopover in New York on our way to England. Some we loved, some less so. In a letter to parents I wrote: “Sunday afternoon we went out to The Cloisters, which is right up at the northern tip of Manhattan. This is a religious museum. Parts of the remains of many old churches of Europe have been brought across and incorporated into the present structure, which keeps as closely as possible to the original styles. In a sense it is a success – some of the old fragments of stonework are very fine, and there are some very fine paintings, altar ornaments, and some magnificent tapestries – the highlight of the whole exhibition. But in spite of their attempts to reproduce chapels, all sense of reverence has been lost – the things are a curiousity for the locals to gawp at, and even sacrilegious.”

As I look back on these youthful letters and these memories, I see opinions about what matters to me already forming and clarifying. Many more experiences of the power of art would come in future years: sitting on a bench in a crowded London gallery, weeping over Georges Rouault’s “The Old King;” gazing in awe at the rose window in Chartres Cathedral; feeling the silence of the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Always, enriching these experiences, the memory of that stunning awakening in New York.

Country bumpkins in New York

The friends we were traveling with chose the hotel, the cheapest they could find. It was on W. 46th Street, just off Times Square. Only one thin hand towel in the grungy bathroom. What to do? We called the desk. A maid appeared, to tell us the towels were not yet back from the laundry. In hindsight, a tip might have made towels magically appear. But we knew nothing about tipping; it wasn’t a part of the culture we knew.

Breaking our 1962 journey from New Zealand to England as young married couple off to see the world, Tony and I had disembarked in New York to visit my sister Evelyn, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University in upstate New York. From there the three of us traveled by Greyhound bus to Baltimore to spend a few days with her friends Brian and Jennifer Wybourne and visit Washington, DC.

Driving with the Wybournes back to New York, where we were to board another ship bound for England, we were wide-eyed at our first glimpse of the New Jersey turnpike. In a letter to parents I wrote: “…one of the most famous of the turnpikes – 150 miles of unhindered 6-lane highway. Then navigating the streets of the city – practically all are one-way, which makes it complicated, and you can imagine the traffic.”

The letter continues: “The next morning we went up to the top of the Empire State building – early, before the mist got up. The view from the top is terrific – you can see the whole extent of New York city – which is saying something.” I look back in memory and see the young woman I was, neck stiff from craning upward at rows of skyscrapers that made deep canyons of the streets, mind agog at the level of luxury displayed in store windows. I remember wandering through several of the huge department stores, feeling lost and out of place.

One day we walked to the tip of Manhattan and back, excited to see Wall St. and Greenwich Village, and to walk on Broadway. I wrote: “We were really footsore by the time we reached the hotel, but then we had the big experience of our trip – riding the New York subway during rush hour. That was some experience. We held each other tightly, and shoved with the rest. Sardines in a can had nothing on the train – but you had to make sure you weren’t pulled out with the rush at each station.” Evelyn, who was taking us out to the Bronx to dinner with the family she was staying with, wrote in her letter home: “I deliberately engineered it to be at Grand Central Station about 5 past 5 at night. It was quite an eye-opener for them…”

On each of the other nights we had the new experience of dining in a restaurant of a different nationality, all quite cheap by New York standards, and all in the same block as the hotel – Greek, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, as well as American – hamburgers and doughnuts.

For lunch Evelyn introduced us to automats. I commented: “We found foreign food much more interesting than American – they process it and vitaminise it, and goodness knows what – the result is rather tasteless.”

In future weeks I’ll talk about other aspect of our first visit to New York: the art, the music, the experience of visiting the heart of the United Nations secretariat.

And yes, a few more threadbare towels did eventually show up in our hotel room.

Other people’s weather

An ethereal music filled the air as Tony and I stepped down from the Greyhound bus at Niagara Falls in March 1962, a music so sweet and high it seemed to come from some magical place. I gazed about me. Nothing but bare trees and an almost empty parking lot. A wind that stung my ears. Then I saw them: icicles, many inches long, hanging from every twig and tinkling against each other with every gust.

Growing up in the subtropical north of New Zealand, I did not see snow until I was an adult. Our winters had heavy rain and an occasional frost, enough to whiten the grass and form thin sheets of ice on puddles. But nothing like this: the gigantic falls themselves half frozen and the temperature the coldest I had ever known. Historical records tell me it was probably about 30°F. (though the wind chill factor would have made it seem colder), and that the winter was pretty much a normal one.

We had broken our journey from New Zealand to England in New York to visit my elder sister, who was completing her doctorate at Syracuse University. As we rode the Greyhound bus upstate to Syracuse, what fascinated me as much as the landmarks my sister pointed out were the piles of dirty snow everywhere. I began to comprehend the northern hemisphere stories I had grown up with, where winter was a time of death and darkness, the weather something to be feared, and the spring thaw a time of great rejoicing.

Having recently passed through the tropical miasmas of Panama, I was also discovering that people could learn to live in places where the climate was not friendly, though the strategies they used to deal with the climate sometimes left us puzzled. In Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for example, where our ship had berthed for a day on its way to New York, we were stunned by the difference between the searing heat outdoors and the air-conditioned iciness inside the big stores.

Tony and I realized then that that we were just starting on the great adventure of learning how the rest of the world lives.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

Old age has its advantages

I’m taking a break this week from tales of my youthful travels to share a poem I wrote as homework in a Stanford Online class: 10 Pre-Modern Women Poets, taught by Eavan Boland. This week we studied “Saturday: The Smallpox” by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Written in 1747 in the voice of Flavia, a young beauty whose face is disfigured by the disease, the poem is a sad satire on the priorities of that era’s fashionable society. Our assignment was to write a poem using the heroic couplet form in which “Saturday: The Smallpox” was written.

Lady Mary, who was herself afflicted with smallpox, was a pioneer in vaccination for this dreaded disease. I find it particularly discouraging that 267 years later, people are still arguing about the value of vaccination against measles, a disease that nearly killed my father when he was a child.

However, my poem isn’t about the ravages of disease, but rather the emphasis on fashion still rampant today. It was a lot of fun to write.

A Grandmother Responds to Flavia

Advancing age has this one recompense,

That I can clothe myself with common sense.

Invisible already to the young,

I’m from the prison of convention sprung,

At last to dress as I have lately dressed,

I don’t wear heels; I’ve never seen the point

Of teetering at risk to ankle joint.

My fingernails are bare of chip-prone paint,

My hair goes where it wills, without restraint.

When grayness first revealed itself, I bought

Some dye, but soon discovered what I thought

Was beauty was instead a bathroom mess,

Despite my brave attempts at carefulness.

For lack of make-up, blame my allergies,

My nose rubbed naked every time I sneeze.

For lack of lipstick, blame Ms Magazine,

Which in the Seventies proclaimed with spleen

That face paint was an INEQUALITY;

If men don’t have to do it, why should we?

So now my silver hair surrounds a face

Where age’s wrinkles have an honored place.

I am content with plainness; jeans and boots

Shall walk me earthward to my simple roots.

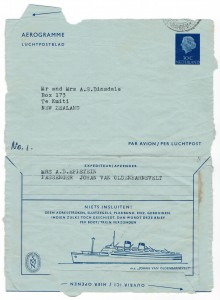

The Mechanical Mules of Panama

My father had a lifelong love affair with things mechanical. When he was in his seventies, I sat him down with a tape recorder. One of his memories was of passing through the Panama Canal. The year was 1920, six years after the canal was officially opened. Dad was eight years old, traveling from New Zealand with his parents and younger siblings to visit relatives back in England. He told me: “I was fascinated with these … I think they call them donkeys. A locomotive type of thing that ran on a rack – rails and rack drive, and those things pulled the ship through from one lock to the other. We had to climb up the steep climb at the end of the lock up to the next level or down.“

Standing at the rail of the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt” in 1962, I shared Dad’s enthusiasm. In a letter to parents I wrote: “I did not realise how exciting [going through the canal] would be. It is an incredible piece of engineering, and extremely efficiently run by the Americans. We got up on deck just as we arrived at the first lock, with Balboa still in the distance, so we really saw the whole trip. We were pulled through the canal by teams of little trains called mules, that ran on a cogged track. It only took ten minutes for the huge locks to fill and empty. It was more impressive too because several other ships were going through the other way at the same time – as we went down they went up, and vice versa. From the time we approached the canal we saw lots of big ships – a wonderful change after seeing nothing at all but sea across the Pacific.“

Standing at the rail of the “Johan von Oldenbarnevelt” in 1962, I shared Dad’s enthusiasm. In a letter to parents I wrote: “I did not realise how exciting [going through the canal] would be. It is an incredible piece of engineering, and extremely efficiently run by the Americans. We got up on deck just as we arrived at the first lock, with Balboa still in the distance, so we really saw the whole trip. We were pulled through the canal by teams of little trains called mules, that ran on a cogged track. It only took ten minutes for the huge locks to fill and empty. It was more impressive too because several other ships were going through the other way at the same time – as we went down they went up, and vice versa. From the time we approached the canal we saw lots of big ships – a wonderful change after seeing nothing at all but sea across the Pacific.“

Dad mentioned seeing an alligator on the bank of Lake Gatun. I did too. My letter continues: “Through the centre of the canal we go through a big artificial lake with dozens of islands covered with jungle. Saw at least two alligators, and many beautiful birds. We were served lunch up on deck so that we wouldn’t miss anything – at the time we were going through the Gatun Locks, which is the biggest group – three locks together.

“The countryside changes very much through the canal. On the Panama side it is all lumpy hills, some of them quite high – the Gaillard cut goes through a fairly low part – about 250 ft. Then on the other side you descend to steamy swamps – now fortunately cleared of the mosquitos that ruined the first attempt at making a canal – the remains of the French project are still visible in parts. Even though this is the dry season, the jungle still looked hot and sticky – I would hate to be there in the wet season.”

The ill-fated French attempt to build a canal began work in 1881, but ground to a halt in 1884 because of engineering problems and high mortality due to disease. The United States took over in 1904. A decade later, by far the largest American engineering project to date was completed, and the canal was officially opened in August 1914.

As the JVO slipped smoothly through the canal, I felt I was part of history, both of the canal itself and of my own family, as I followed my father’s journey and shared his enthusiasm for those mechanical mules.

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes

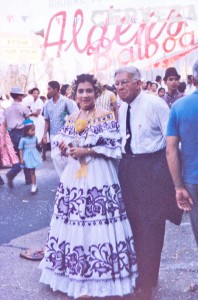

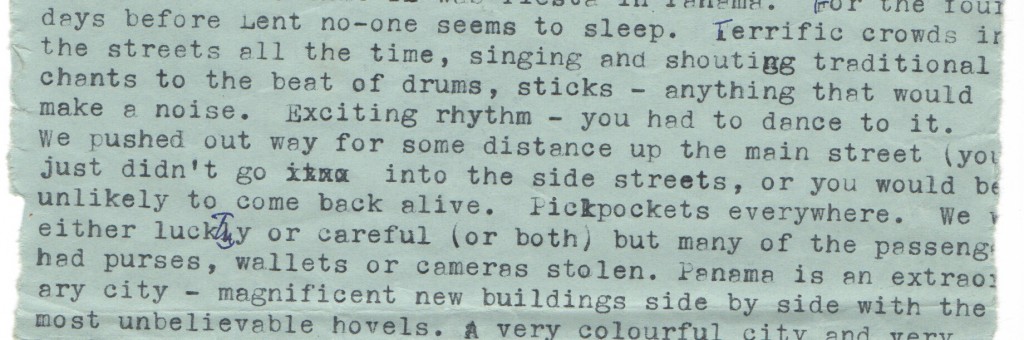

Encountering Carnival in Panama

Panama City, March 1962

I had no idea that we’d arrive in Panama during Carnival. Even as our ship sidled into port at the end of the Pacific crossing, we could hear the sounds of it, the ramshackle city pulsing to a beat like none I’d ever heard. Once docked and allowed to disembark, we passengers pushed our way through dense crowds of people, among which wove decorated floats, costumed dancers, bands crowded onto the beds of battered trucks, men on the street beating drums or, lacking drums, the metal sides of the trucks, all singing and shouting to the heady Latin American rhythms. Sometimes a figure in fantastic costume would pass, surrounded by a group of friends singing and shouting together.

Everyone dresses up for Carnival. I was fascinated to see women wearing the pollera, the Panamanian national costume. Spanish in origin and atmosphere, the dress is of white cambric, embroidered in a bold floral pattern in a contrasting color, usually red, black or blue, each frill trimmed with a border of hand-made lace.

At roadside stalls we watched Panamanian boys scrape blocks of ice for the local sweet. They pressed the ice shavings into a paper cup, and poured over it a bright colored syrup and condensed milk. A bit tasteless, but very refreshing.

Passengers had been warned before we disembarked about the level of crime on Panama’s streets. There’s a hint of bravado in my letter to parents: “You just didn’t go into the side streets, or you would be unlikely to come back alive. Pickpockets everywhere. We were either lucky or careful (or both) but many of the passengers had purses, wallets or cameras stolen.”

What I didn’t write about was the effect on me of the incessant drums, the shouts and snatches of tune, the rhythm syncopated, hypnotic. I wanted to drown in it, swirl with the dancers forever into the glittering ocean of color and sound. But like the hawsers holding the ship to the dock, my past tethered me: syrupy fifties songs about marriage and children, strictures on proper behavior, appropriate dress. We wandered in the crowd for a day, then moved on.

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.

Scrabble and other equatorial diversions

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

“This shipboard life is curiously hypnotic,” I wrote to my parents a few days out from Wellington in February of 1962. “Absolutely nothing to do all day but sit & watch the waves go by. You soon find it practically impossible to do any thing else.” The ‘what else’ we found as we sailed for two weeks across the tropical Pacific was the game of Scrabble. Every afternoon we gathered on the deck with a group of shipmates, one of whom had a Scrabble game in her luggage. While the nautical miles accumulated, we bonded over the game, and have continued to stay in touch with some of them over the many years since.

After the storms and seasickness of the first week, we had perfect weather: sunny days, calm seas, and just enough breeze to keep things cool. I decided that ocean voyages were not so bad after all.

I had time to dream. When my husband Tony and I carried our bags up the gangplank of the “Johan van Oldenbarnevelt” earlier that month, bound for New York and then England, I felt I was walking in the steps of my role model, the great New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield, who also went abroad at a young age to pursue a literary career.

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

As the familiar constellations of the Southern Hemisphere receded southward, we discovered the truth of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s lines in “Rime of the Ancient Mariner:”

The Sun’s rim dips; the stars rush out;

At one stride comes the dark

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

My letters comment on the group of people we got to know: “… Mainly the crowd from our table. We have had some very good discussions and arguments about all sorts of things. The brain needs some exercise after sitting looking at the sea most of the day. So does the body – we are getting good at deck tennis (our own rules), and have spent quite a bit of time in the swimming pool. When the sea was rough the water in it sloshed back and forth terrifically, but is better now.”

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

A few highlights of the voyage float into my mind. A visit to the bridge, where I was allowed to steer the ship. Watching flying fish and dolphins leap out of the water close to the ship. The obligatory visit from King Neptune the day we crossed the equator. But mostly I remember playing Scrabble on deck with our new friends, while Indonesian stewards in white jackets rattled tea-trolleys.

I haven’t played Scrabble in years, and don’t remember what happened to our old game set. But this week we bought ourselves a new one. Nostalgia filled my heart as I pulled out from the bag a handful of little wooden tiles.

JVO photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet, which contains 55 years of letters, notes and memorabilia.

Magical Day on a Tropical Island

I have never returned to Tahiti. I prefer to remember it as it was one special day in February, 1962. When I think of that day, a melody from the musical “South Pacific” fills my head.

I have never returned to Tahiti. I prefer to remember it as it was one special day in February, 1962. When I think of that day, a melody from the musical “South Pacific” fills my head.

In a letter to my parents I described coming in to port: “We got up early in the morning, in time to see us come through the passage between Moorea and Tahiti. Moorea is the most enchanted shape of any island – fantastic contorted peaks rising up out of a faint mist, and shimmering in the morning sunlight. … The sea perfectly calm, glassy inside the reef, and a sparkling sunny day.“ We had plans to explore the island by motor scooter, so after wandering around Pape’ete until we found the rental place, we “followed our noses and found ourselves on the coast road.

In a letter to my parents I described coming in to port: “We got up early in the morning, in time to see us come through the passage between Moorea and Tahiti. Moorea is the most enchanted shape of any island – fantastic contorted peaks rising up out of a faint mist, and shimmering in the morning sunlight. … The sea perfectly calm, glassy inside the reef, and a sparkling sunny day.“ We had plans to explore the island by motor scooter, so after wandering around Pape’ete until we found the rental place, we “followed our noses and found ourselves on the coast road.

“Took a turning up into the hills – very steep, narrow winding road up to a lookout point – excellent view over Pape’ete and out to Moorea. Hibiscus everywhere, vivid red, pink, yellow – any colour you can think of. The vegetation is all a bright yellowish green, and the soil is bright red.

“Coming down – discovered that scooter’s brakes were practically nonexistent – slightly hazardous! Continued along the coast road, looking for somewhere to swim, asking the way in our best French. We were agreeably surprized all day that we could understand and make ourselves understood. Of course they speak much more slowly than the French of Paris – hotter climate.

Found a good beach after a ride down a track through a coconut grove – i.e., very large rough boulders – every so often the scooter would jam and we would have to get off and lift her over. Came out between the houses of two Tahitian families. Fishing nets hung along the beach to dry – used them as a changing tent – not that one would need to worry in Tahiti.  Just wallowed in the lukewarm water – crystal clear, and watched the tiny tropical fish nibbling at our toes. Pretty little things, mostly black and white, though some coloured ones, all spotted and striped. Eavesdropped on the Tahitian families at home – fascinating. A very happy, leisurely people – we were amazed with the genuine friendliness we met everywhere.

Just wallowed in the lukewarm water – crystal clear, and watched the tiny tropical fish nibbling at our toes. Pretty little things, mostly black and white, though some coloured ones, all spotted and striped. Eavesdropped on the Tahitian families at home – fascinating. A very happy, leisurely people – we were amazed with the genuine friendliness we met everywhere.  We saw a fishing canoe come in, manned by six men – and with an outboard motor. Also watched women fishing along the shore – four of them splashing about in their sarongs and laughing and singing as they pulled in the net.”

We saw a fishing canoe come in, manned by six men – and with an outboard motor. Also watched women fishing along the shore – four of them splashing about in their sarongs and laughing and singing as they pulled in the net.”

My letter goes on to describe people-watching at an outdoor café back in Pape’ete: “Easy to pick tourists from the ship – they stood out a mile – the footsore look, paler complexions, brand new plaited straw hats – we got one each too, very fine models for roughly 6/- [about $US 0.42] and were very glad of them all day.” Then an evening visit to a tourist hotel for a display of Tahitian dancing. I commented: “The tourist trade is thriving here, especially since the Americans have just finished making a film here, Mutiny on the Bounty. They have sent prices up. The hotel was one of these places that you know are touristy and a bit artificial, but exciting all the same. Guests sleep in native-style bungalows, and the dance floor was also in native style, with carved supporting poles, thatched roof, and open sides. Dimly lit with coloured lights inside bamboo fish traps. Tables both inside and outside on the grass on the shore of the lagoon – that was where we were. All round the edge, kerosene torches on poles to keep away the insects. A huge full moon shimmering on the water, a jetty to wander out and watch the fish. European dancing (Tahiti version) with floor shows – native dancing. The most exciting dancing I have seen. Fantastically fast hula to the urgent throbbing of native drums. Later in the evening the slower, more graceful hula to drums and singing.

“When the show closed – about 1 a.m., there was a general move toward “La Fayette,” which turned out to be a pretty low dive several miles the other side of Tahiti, and was the most terrific entertainment yet. Dim lights, floor jam-packed – mostly pretty well under the weather. Lots of people from the ship – stewards and passengers, with Tahitian girls. No inhibitions – man, what an education! Got back to the ship about 4 a.m. – shore leave finished at five – and wandered round on the wharf, where women were still sitting patiently at souvenir booths – they had been there all day. Spent our few remaining coins on postcards, etc. Many of the passengers waited up to see the boat out, but we piked and went to bed. Very hard to say goodbye to the place.”

In closing my description of the day, my first in a country other than New Zealand, I wrote: “We found it rather difficult getting used to being tourists – you feel so brash and raw, and totally ignorant, and tolerated by the local population mostly as a useful source of income. I think I would much rather go to a place to live for some length of time – it would give you a much better idea of what it is really like. We were lucky in getting a glimpse of Tahitian families about their ordinary life – that I think was the best part of the whole day. But it was only a tantalising glimpse – enough to whet the appetite.”

In closing my description of the day, my first in a country other than New Zealand, I wrote: “We found it rather difficult getting used to being tourists – you feel so brash and raw, and totally ignorant, and tolerated by the local population mostly as a useful source of income. I think I would much rather go to a place to live for some length of time – it would give you a much better idea of what it is really like. We were lucky in getting a glimpse of Tahitian families about their ordinary life – that I think was the best part of the whole day. But it was only a tantalising glimpse – enough to whet the appetite.”

All photographs are by Tony Eppstein.

Maureen is exploring the contents of an old black filing cabinet in her attic, which contains 55 years of her writing notes and memorabilia.