Dolphins of Yesteryear

A 55-year-old news clipping brings back memories

An old black metal filing cabinet sits in my cluttered attic. Stuffed into its four drawers are fifty-five years of my stories, some published, most not. Sooner or later someone will have to dispose of all the dog-eared pages and travel-worn manuscript boxes. In the meantime, I’ve set myself a little project for this blog: go through the files and find pieces of my past that you, my readers, might find interesting.

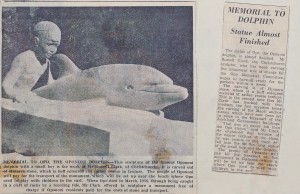

Here’s one, to start us off. On January 6, 1960, I was fresh out of college, and this was my first day on the job as a cub reporter at The Press, Christchurch, New Zealand’s morning newspaper. My boss, the city editor, handed me a four-year-old clipping about the death of Opo, a bottlenose dolphin who chose to join children at play in the surf at Opononi, a beach settlement in the Northland region. The grieving residents had commissioned a statue. “Here, update this story,” he said. “The sculptor lives in Christchurch. His phone number’s in the book. I’ve heard he’s nearly finished.”

I had a pleasant conversation with Russell Clark, the sculptor, who was making the sculpture free of charge as his tribute to Opo. It is of Hinuera stone, which is buff colored and coarse in texture. The sculpture was indeed nearly finished, and would be shipped to Opononi the following week. I was so proud when my little story appeared exactly as written, along with a nice photograph, in the next morning’s edition, having survived unscathed the eagle eyes of The Press’s copy editors, gruff eminences who ruled from a curved dais in back of the press room.

I did not meet Opo, but have my own dolphin memory. We were returning from a family vacation on Tuhua, an island offshore from Tauranga. The day was brilliantly sunny, the launch was bouncing through waves, and I had just learned that I’d been awarded a national scholarship to attend university. A school of dolphins surrounded the boat. Leaping joyously through the waves, they escorted us back to land. As I stood at the bow, I felt like a princess.

I am thankful

I am thankful today for my new refrigerator. Our old one died a few weeks ago. Its replacement, a New Zealand-made Fisher & Paykel, was delayed by labor problems at the Los Angeles docks and eventually had to be unloaded in Vancouver and trucked down to Mendocino. Meanwhile Canclini’s, our local appliance dealer, gave us a smallish loaner, which has been parked out in the garage. We have gotten used to traipsing back and forth carrying milk or butter, and had set up ice chests on the back porch in preparation for an overflow of drinks and produce to feed our visiting family and friends during the Thanksgiving holiday.

It would be inconvenient, but we would cope. We’ve survived worse holiday crises. There was that time thirty-five years ago when we were remodeling an old house in Palo Alto. The kitchen walls were stripped down to the studs. Crates of new kitchen cabinets filled the living room, blocking access to the fireplace. I noted in my journal: At least I did warn [our friend] Judi that we might be picnicking amongst the mess. … [Our teenage sons] moved the kitchen cabinets today so that the sitting room & fireplace are usable again. Until the gas lines are reorganized, we have no heat, and the weather is getting colder, so it was important to be able to have a fire in the fireplace. We have plenty of firewood at least. On 11-30-1979 I noted that we had a delightful ‘old-fashioned’ Thanksgiving with Judi and her son Mark, who had been friends with our sons since they were little boys.

Thanksgiving a year later, the second floor completely rebuilt, we were waiting for the new roof to be completed and keeping a wary eye on the weather.

Journal 11-24-1980: The disaster finally happened over the weekend – eight weeks good luck couldn’t last. It rained Friday evening. Trusting in the plywood sheathing, we didn’t cover the floor with plastic all that thoroughly – a mistake. Throughout the night new drips opened up in the ceiling, mainly in the places where old plaster joined with new or at best was sagging or cracked. Buckets and towels all over the floor. We had to move out our bed because of a drip above us, which turned into a downpour slightly further along the crack about 3:00 am. David’s room also, where old gable met new roof, had a line of drips. Nasty watermark on the ceiling (most of which we were going to redo anyway). No permanent damage to floor. Spent all Sat. cleaning up in preparation for Thanksgiving, which I suspect is going to be as improvised as it was last year, though in different ways. Kitchen is finished, though with temporary lighting (as is all of ground floor). Can’t use the fireplace – need extension flue, which is still being built. Will have to decorate at eye level, prevent people’s eyes from moving upward, because of water marks on ceiling and upper walls. Stairwell still a mess of lath and ladders.

We survived that Thanksgiving holiday too. But this year we had a last-minute rescue. The kind men from Canclini’s brought us the new fridge on Wednesday morning and also left us the loaner until after the weekend, just in case we needed extra space. The turkey sits there now. In a little while, I’ll head out to the garage one more time and bring it in to the oven.

Thank you, Canclini TV & Appliances, and Happy Thanksgiving everyone.

Going Dark

In 1966, my friend Diana Neutze developed multiple sclerosis (MS). She was not yet thirty years old.

I first met Diana about ten years before this, when we shared English Lit. classes as freshmen at Canterbury University in Christchurch, New Zealand. During school breaks we worked as kitchen hands at the same remote fishing camp. I was part of her wedding, and she of mine. We lived next-door to each other as young marrieds, and shared survival tips as penniless expatriate mothers of small children in London. Even after I moved to California and she returned to New Zealand, we stayed in touch as best we could.

For decades Diana’s illness came and went. She learned to live with it, devising ingenious stratagems for making sure she stayed mobile and independent. Whenever possible, she refused medications. All she had left, she said, was her mind, and her ability to find joy in music and the beauty of her garden. Painkillers took that clarity of mind from her, and this she could not allow. Right up until the end she was writing and publishing poetry. (I reviewed a recent book in these pages) I introduced her, via email, to a quadriplegic friend who got her started with voice recognition software. When she could no longer edit using one finger on a keyboard, or see to read, she dictated edits to a carer.

Diana and I traded poems and, as her body slowly but inexorably closed down, thoughts about death. She was in my mind when Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino invited local poets to respond to Wendell Berry’s poem “Going Dark” at a 2012 Winter Solstice event. I sent the poem to Diana, and included it in my new chapbook, Earthward. When I spoke to Diana via Skype in April 2013, three days before she died, she accepted my promise to dedicate Earthward, to her memory. At her request, my poem, “Going Dark,” was read at her funeral. Here it is:

Going Dark

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

— Wendell Berry

My friend’s body is a brown leaf,

shriveled and curled inward.

Pain is a constant, yet

the fierce flame of her will

refuses surrender.

It’s not death’s darkness she resists

but the loss of a self transfixed

by what is beautiful:

a Bach air, the light

through her walnut tree.

This dark she speaks of

has no scent of earth,

no draft from unseen wings,

no sudden rustle in the undergrowth.

What can I say to her, and to myself,

this season of gathering in

our lives against the rainy dark,

against the ancient fear

that light will not return?

Just this: a dry leaf

fallen to ground disintegrates,

becomes the food that nourishes

all that sweetly blooms and sings.

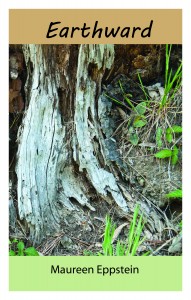

My chapbook Earthward is available from Finishing Line Press. The direct link is: https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

Some of Diana Neutze’s poems can be read on her blog site, Living With Multiple Sclerosis.

My new poetry collection

I am excited to announce that Finishing Line Press is now taking pre-publication orders for my new poetry collection, Earthward. It can be ordered now and will be printed and shipped in October. You can order online from the publisher at https://finishinglinepress.com/product_info.php?cPath=4&products_id=2129

The cost is $14 plus $2.99 shipping. The publisher bases the size of the print run on how many pre-publication orders they receive, so I hope you’ll consider adding to my tally. Please feel free to suggest this book to others you think might be interested too.

The poems in Earthward explore the cyclical patterns of life. Here is a sample poem:

Osprey With Fish

Undercarriage of leg and talon

joins two bodies similar

in sleekness,

twinned

as life and death conjoin

in a continuum

of nourishment.

Huge wings slow over forest,

a fading cry.

I’ve been honored to receive reviews from poets I admire:

With a naturalist’s eye for the precise and sensuous image and a writer’s care for the precise and sensuous word, Maureen Eppstein plants our human griefs into this book, roots them, and invites them to quicken into new life.

—Jane Hirshfield, author of Come, Thief

What captivates me about Earthward is the way Maureen Eppstein transforms ordinary landscapes into miraculous acts of affirmation. Turning compost becomes an opportunity to ponder death and resurrection, braiding garlic reminds us of the “pleasure taken in braiding the hair of the beloved”. This is poetry of quiet lyrical depth, that reconnects us with land and spirit. Earthward invites us to stand deeply rooted in each moment, “in awe and wild surmise at all this human brain can not yet comprehend.”

—Devreaux Baker, author of Red Willow People

In Earthward, Maureen Eppstein unites what would break us with what will bring us back to life. The wild ones, like us, must eat, and so kill. Lost sisters are mourned by proxy. Some things we love are transplanted and transplanted again, surviving and sometimes thriving. The tenacity Eppstein describes is the foundation of our lives. There are those who say that to write about the extraordinary one must look lovingly at the ordinary. Eppstein knows where, and how, to look.

—Camille T. Dungy, author of Smith Blue

Here’s a brief bio:

Maureen Eppstein is the author of two previous poetry collection: Rogue Wave at Glass Beach (2009) and Quickening (2007), both published by March Street Press. Quickening was also first runner-up in the 2007 Finishing Line Press/ New Women’s Voices competition. She has been a finalist in several other book contests. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including Poecology, Calyx, Basalt, Written River, Sand Hill Review, and Aesthetica 2014, and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Crossing the boundary between the arts and the sciences, her poems have been included in a textbook on computer graphics and geometric modeling and used in a university-level geology course.

Josh Weil novel launched

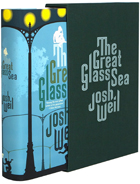

I’m so proud of young novelist Josh Weil, whom Mendocino Coast Writers Conference picked as a rising star and invited to be on faculty at our 2013 conference. Here’s news from Josh worth sharing:

literary prize, the most incredible first-edition program I’ve ever seen, my complete book tour schedule—but there are two reasons, above all else, that this issue of The Gazette is a pretty special edition.

literary prize, the most incredible first-edition program I’ve ever seen, my complete book tour schedule—but there are two reasons, above all else, that this issue of The Gazette is a pretty special edition.“[An] impressive debut…As broad as its themes are—touching on political, philosophical and historical divisions—Weil’s first novel is rooted in family and fine storytelling; it’s an engaging, highly satisfying tale blessed by sensitivity and a gifted imagination.”

“A tale of longing and sadness, threaded by Russian folklore and heavy with the weight of love…resplendent and incandescent.”

“A well-timed dystopian tale, the novel beautifully details both the politics of [an] hypothetical Russia—“oligarchs bred beneath the clamp of communism let loose upon loot-fueled dreams”—and its impact on one small family.”

And the first newspaper review (out even before the official publication date!) was even better:

“If complex literary novels really are done for, Josh Weil must’ve missed the text message. His formidable “The Great Glass Sea” knits together strands of traditional Slavic folklore and futuristic speculative fiction to create a passionate reflection on technology and personal happiness. Spanning almost 500 pages, the novel poses mind-bending questions about politics, ecology and the ambivalent closeness of siblings…Weil pulls off dazzling strokes of storytelling…His distinctive voice obliges readers to slow down and swish certain passages around before swallowing…While keeping the sophisticated themes afloat (science vs. nature, the state vs. the individual, family obligation vs. ambition), almost every page flows with respect for the flawed, endearing heroes, Dima and Yarik. Pushing the envelope on literary artistry even further, each chapter begins with a pen-and-ink illustration by the author….A genre-bending epic steeped in archetypal stories, “The Great Glass Sea,” rises above the usual Cain-and-Abel formula by way of sensitive, resourceful craftsmanship.”

And here’s me, now, signing off and saying thank you, again, for continuing to care about what that tyke’s grown up to love, what the writer he became now does, these words on a page that I am so lucky to be able to share with you.

Doing by Not Doing

I thought I was retired from running the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference. But life happens, and so do medical crises. So I’m back as Acting Executive Director, scrambling to pick up the threads of all the detailed tasks that make up a successful conference and continue weaving them into a sweetly patterned braid.

I’ve done it before, several years of befores. My challenge is to keep calm, level-headed, unstressed. I know that to do my job well, I need to take time to do nothing.

This morning Tony and I took one of our favorite walks: from Laguna Point at MacKerricher State Park south along the cliff edge to Virgin Creek Beach, then footprints on smooth wet sand to where the water of Virgin Creek ripples and glitters as it crosses the beach to the sea. There we leave the beach and, picking up our pace, take the weather-beaten old haul road back to the Laguna Point parking lot.

This afternoon as I sit on my front porch, a white-crowned sparrow is singing from a nearby bush. Hummingbirds are working over the purple Mexican sage and yellow sticky monkey flower in front of me. I hear chirps from newly hatched Stellar’s jay chicks as a parent flies in to their nest in the wisteria vine. A violet-green swallow has come and gone from the porch corner cavity where they’ve sometimes nested. Two stems of dry grass dangle from the cavity. Not a good place this year. I warn them in my mind to beware the predatory jays.

Inspired by a talk a year or two back by Lewis Richmond, author of Aging as a Spiritual Practice, I am learning to meditate. It’s hard to push away the clutter of to-do lists, but I think I am making progress.

The mission of the Mendocino Coast Writers Conference is to offer a place where writers find encouragement, expertise and inspiration. As executive director, my encouragement comes from the support and expertise of a wonderful team of volunteers, some of whom have been helping to run the conference for nearly all of its twenty-five years. My inspiration comes from the beauty of the pattern I braid from all these threads of tasks in my hand, its colors imbued with the memory of sea and headland, forest and garden, its thread tension even, unmarred by crises.

For the sake of all the writers who leave Mendocino Coast Writers Conference inspired by the supportive atmosphere the conference team creates, I can do this.

The Doll

As a child, I was a trial to my mother. Throw epithets at me and I’ll own them: mean, resentful, difficult. I was jealous of my sister Evelyn, one year older than me. She was the beautiful one, with the blue eyes and golden ringlets my mother adored, the one with the heirloom china doll with its own blue eyes and golden hair, handed down from some relative or other.

Another word: ungrateful. That describes me this week, when an email from my youngest sister Alison arrived. She and my other sister, Patricia, had been doing a spot of spring-cleaning and had found my childhood doll. Did I want it? No, I replied, flooded with guilt about that unloved “child.”

A memory. I am maybe five or six. I am lying on my parents’ bed, sobbing and sobbing. I have been put there on time out for fighting with my cousin. Lee was a few months younger than me. She was then an only child, with parents who doted on her. Lee had a fancy new baby doll. Evelyn had the exquisite china doll. We played mothers and babies, but all I had for a baby was a yellow knitted creature of indeterminate parentage. I picked a fight. Lee and I came to blows. Time out. I sobbed at being hauled in from play, at the unfairness of life.

The door opens and Lee creeps in.

“What do you want?” Surly, still angry.

“I know a secret. You’re not supposed to know. Your Dad’s fixing Sally.” Sally was another heirloom, a celluloid baby doll so fragile she was constantly on Dad’s workbench with a broken limb.

An adult arm reaches through the half-open door and drags Lee out. It gives me satisfaction to hear her being slapped and scolded. A few minutes later my mother appears. “You might was well come out, then. It was supposed to be a surprise.”

Dad’s repair to Sally lasts no longer than usual. But at least I have a glimmer that someone cares. For my birthday I receive a large package from my parents. It is a doll who can close her eyes in sleep. But not a beautiful doll. She looks like me: straight dark hair cut into bangs like mine, brown eyes, a tiny mouth, her features molded in some coarse composition material. I play with her, of course, but do not cherish her.

Seventy years later, the doll’s portrait shows up in my email in-box. Where on earth has she been all these years, I ask my sisters. It turns out they found her among the effects of our eldest sister, Evelyn, who died several years ago. Had Evelyn kept her safe all these years? Or had she rescued her from our mother’s cluttered house when she helped move Mum into an assisted living apartment? We’ll never know. But it humbles me to think that both of them cared enough to keep the doll safe when her oblivious “mother” abandoned her.

The doll is now officially an antique, sister Pat tells me. She’s somewhat the worse for wear. Her hair is gone. It looks like she’s fallen on her face a few times. I feel a rush of tenderness for the forlorn creature she has become. I’ve asked my sisters to find her a good home.

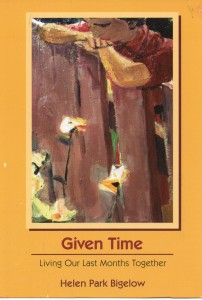

Given Time

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

Given Time: Living Our Last Months Together by Helen Park Bigelow, which I’ve just finished reading, is an unflinching look at the emotional and physical landscape a care-giving spouse or partner must traverse in those last months before death. Helen’s husband Ed had a melanoma removed in 2005. The surgery seemed successful, and regular follow-up tests and scans at first came out clear. But three years later the melanoma returned and metastasized throughout his body.

To offer a flavor of the book, I can’t do better than to quote the blurb by Fithian Press, the book’s publisher: “The book deals honestly with the process of dying, an ordeal shared by both of them. It also deals with the process of staying alive and in love until the ordeal is over… [Bigelow] writes with brutal honesty about her anger and grief over what has become of her husband and herself. The book isn’t a manual about how to take care of a dying man, but it makes the reader well aware of what a grueling job it is. “So this is it,” she writes. ‘This chemo routine is the rest of our lives together…and goddamn it, it’s going to be as good for both of us as I can make it.’ ”

Reading this book set me to thinking about my husband’s and my circle of friends. We’re all of an age where we’re facing mortality, both our own and our partners’. Physical infirmities creep up on us. Memories start to fail. The mechanisms of the heart become clogged. I know we’ll all do what we have to do, to the best of our abilities, when loved ones need our care, and that, if we are the ones whose lives are ending, we hope to have someone as caring as Helen to tend our passage. I’m grateful that services such as hospice are available. Most of all, I am inspired by Helen’s love of beauty to seek it out in my own life. Whether my time is counted in decades or years or even months, I want every day to be touched by grace.

Word Art

I spent this morning thinking about the intersection of writing and art — how we can be moved by a piece of art that involves words, even when the writing is undecipherable. Or when you are ignorant of the language, as I was recently in Istanbul, where I was captivated by the Arabic script that decorated walls of mosques and palaces.

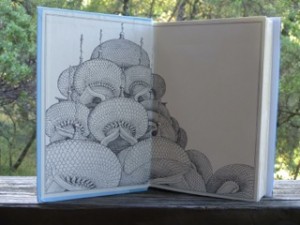

Last night was the opening celebration in Mendocino for the show “Boundless: Art of Letter, Word and Book,” which curator Janet Self describes as a “hands-on conversation about art, language, books, and engagement in the modern age.” I have several pieces in the show: a poem collaged onto a cast paper fish, the poetry box from my vegetable garden, a handmade book that employs a complex flower-fold structure (suggested by Alisa Golden in “Making Handmade Books”), plus some broadsides and tiny chapbooks.

As I looked around the room, I saw uses of the written word that sparkled with creativity. Janet has posted some pictures on her Flockworks blog site. Among my favorites were “House of Cards,” a walk-in house shape whose walls were linked postcards from all over the world, sent years ago to members of the same family, and inherited by the house-maker. I chatted with Harry Van Ornum, a calligraphy student who, having filled his practice paper with lyrics by a favorite singer, turned the paper sideways and continued, making of the words an abstract form. Janet Self, faced with a huge collection of her father’s Reader’s Digest Condensed Books that no thrift store would take, repurposed the pages into large, flowing geometric sculptures.

My favorite encounter was with a young man who stood entranced in front of a calligraphic painting by the late Jim Bertram, one of the artists who helped found the Mendocino Art Center in the 1960s. It was part of a collection being sold as a fund-raiser for Flockworks, the tiny nonprofit that creates such community art projects as the “Boundless” show.

“Excuse me,” he said. “Can you tell me if that calligraphy is in some language?”

Having met and written about Jim Bertram not long before he died, I was able to tell the young man that no, the beautiful shapes were not words. I told him about the quote I found while researching this artist: Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.

“Now I really want that painting,” the young man responded. “I don’t have any money. But next payday, I’m coming back to buy it.”

At Gallipoli

The Anzac Day memory floats up from my childhood: gray dawn in a small New Zealand town, plod and shuffle of marching feet, old men in uniforms button-stretched across their chests. The oldest of the veterans lays a wreath at the foot of a cenotaph where names are inscribed: casualties of the First World War.

When the war started in 1914, New Zealand was a British colony of less than a million people. Eager to come to the aid of the mother country in her time of need, more than 100,000 men signed up, and well over half of these were killed or wounded. A place name that crops up often on the marble tablets of small New Zealand towns is Gallipoli, Turkey. Seeking to take Constantinople, Winston Churchill, who was then First Lord of the Admiralty, sent the Australia and New Zealand Expeditionary Force (the ANZACs) to storm the Gallipoli Peninsula, which overlooks the Dardanelles, a channel connecting the Aegean Sea to the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea. Writing in Slate, journalist Andrew Curry comments: “Though Gallipoli was a small conflict compared with landmark battles of the first world war like the Somme, the battle for the narrow peninsula contains the story of the war in microcosm: the fatal bravado, the futile fighting, the error-prone assumptions made by politicians and generals, and the killing fields that decimated a generation of young men.”

At dawn on April 25, 1915, the ANZACs landed at a small cove surrounded by steep cliffs. They met stiff resistance from Turkish troops. For nearly nine months the two sides fought and died, until finally the ANZACs withdrew. The website for the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage comments: “It may have led to a military defeat, but for many New Zealanders then and since, the Gallipoli landings meant the beginning of something else – a feeling that New Zealand had a role as a distinct nation, even as it fought on the other side of the world in the name of the British Empire.”

The rugged landscape of the peninsula is now a Turkish national park, filled with cemeteries and monuments to the dead of both sides. I was there last week, almost ninety-nine years after that tragic venture. At every memorial site, huge semi-circles of temporary bleachers were being set up for the Anzac Day ceremonies, which will be attended on April 25 by tens of thousands of Turks, Australians and New Zealanders.

With us also at Gallipoli last week was a group of New Zealand high school students. We had met them the previous day in Troy where, in the shadow of a modern Trojan Horse sculpture, and with “ancient Greek” costumes rented from a nearby stall, they were having an exuberantly good time re-enacting battle scenes from Homer’s Iliad.

This day at Anzac Cove the mood was markedly different. With solemn steps the students inspected the graves, where the ages of the dead were little different from their own: seventeen, eighteen, twenty-four. One young man passed out red lapel poppies to visitors, including our American tour group. We watched as one by one the students approached the cenotaph, placed their poppy at its base, and stood a moment with bowed head.

A New Zealander by birth, I have not lived in my home country for fifty years. Nevertheless, that day of pilgrimage I carried with me a small New Zealand flag. Following the students’ example, I attached my poppy to the flag and placed them both in the drift of red poppy emblems that lay like fallen petals at the cenotaph’s base. I thought of the stories from Gallipoli of Turkish and ANZAC soldiers who bombed each other by day and in the evening shared cigarettes and rations and helped tend each other’s wounded. I thought of the kindness of our Turkish tour guide who reorganized the tour schedule so that my husband and I could visit the New Zealand memorial site. I thought of the words of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who led the Turkish troops, and later went on to become the founder of the Turkish Republic. They are engraved in stone at Gallipoli:

Those heroes that shed their blood

And lost their lives.

You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country.

Therefore, rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies

And the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side

Here in this country of ours,

You, the mothers,

Who sent their sons from far away countries

Wipe away your tears,

Your sons are now lying in our bosom

And are in peace

After having lost their lives on this land they have

Become our sons as well.