End of an Era for Surfwood Barn

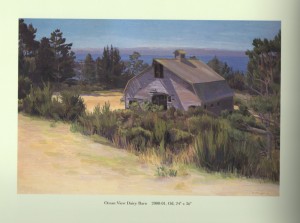

Our local landmark is being demolished. We’ve known it as the Surfwood Barn for the fourteen years we’ve lived here in the Mendocino Coast. It was originally part of the Joy Ranch, and then the Ocean View Dairy, which supplied milk to Mendocino from 1914 to 1939. Since then it has quietly decayed, and has been a favorite subject of plein air painters for decades. This 2001 painting by artist Kevin Milligan is from his book Mendocino: A Painted Pictorial.

The barn now sits on one of the parcels of the Surfwood IV development. We pass it daily on our walks around the neighborhood. We knew that the building, which has been held together for years by aircraft cable, was in a dangerous state, and the current owners of the property had received a demolition permit.

But the arrival of heavy equipment still came as a shock and a sadness.

Encounters with Newts

Now that our rains have finally started, the newts have come out of hiding. Last week I spent a couple of days at Green Gulch Farm, a Zen Buddhist retreat center and organic vegetable farm near San Francisco. California Newts were all over the paths. Their brown skin smooth, their underbellies a brilliant golden yellow, they were marching to the streams where they breed.

This morning we had to step around another California Newt on a path at the Mendocino Coast Botanical Gardens, a little one in its rough-skinned terrestrial phase. It was reluctant to move, since it was busy consuming a large earthworm; the last half-inch of the worm still hung from its mouth.

These encounters reminded me of visiting Montgomery Woods some years ago, when their close relatives the Red-bellied Newts were everywhere. I became fascinated with the story of their breeding migrations and wrote this poem, which was published in my 2007 chapbook, Quickening.

Red-Bellied Newt (Taricha rivularis)

What stirs, with the rain, that urge to return?

Some years she ignores the tingle in her nose,

the scent of that particular section of stream

where under a stone she hatched into a nymph,

then played for a year in the rippling water

before crawling transformed up the bank.

Summers she hides. Home is a secret hollow

under gnarled redwood roots in the ancient grove.

Some winters too. But once in a while, when the rains begin,

she emerges to make the journey to her breeding place.

Purposeful, she crawls, the red of her feet and belly

bright against the redwood duff,

navigating by smell to the rocky stream a mile away,

not home exactly, but the place she came from,

that pulls her back as it pulled her mother back.

Here she will mate, immersed in the water that gave her life,

deposit the fruits of her procreation under a stone,

then wander off to find good forage for the summer.

For thousands of years, as the giants grew overhead,

her kind have made this journey, secure in their faith

that the stream will still flow clear and fast over rocks.

They raise a question: what pulls us humans,

and to what deep places, and what is it we deposit,

like fertile newt eggs on the undersides of stones?

The Standing Still Beings

With enough imagination, any group of two or three lines or dots can become a face. Sunlight filtering through the forest one afternoon this week made me see faces in an old redwood stump I passed as I strolled down the service road to our neighborhood’s pump house in Jack Peters Creek. The “eyes” and “mouth” are actually slots hacked by long ago lumberjacks to cantilever the boards on which they would have stood to saw down the giant tree.

I was drawn to these “faces” because of a recent New Yorker article, “The Intelligent Plant” by Michael Pollan. In it, Pollan notes how wary many scientists are of any hint of parallels between animal senses and plant senses, or of suggestions that plants have intelligence, which he defines as “capable of cognition, communication, information processing, computation, learning, and memory.” Pollan goes on to describe a number of plant studies that do indeed demonstrate such capabilities.

The problem is language. The words we have for intelligence in the animal world (brain, neural networks, etc.) and for the tools of sensory information (ears, eyes, nose, etc.) don’t work for beings whose mode of communication is complex biochemicals: pheromones transmitted by leaves through the air, and electrochemical signals sent by root tips through a network of mycorrhizal fungi. It’s as if we were trying to comprehend and describe the lives of beings on an alien planet.

What I took away from Pollan’s article was a renewed respect for the beauty and complexity of our natural world, and a renewed awareness of how much we humans don’t yet understand. I know the “faces” are just human-made gashes in the trees. But they serve to remind me that I, who have legs to move around, live among the standing still beings, of whose lives I am ignorant.

Down by the Thames

Fifty years later, I’m startled to see the names of English villages I once knew show up on the BBC international news. Huge storms slamming the U.K. have flooded the Thames Valley west of London. I remember Datchet. My husband found his first job there when we moved from New Zealand to England in the early 1960s. On a map this area just west of Heathrow Airport shows more blue than green. The River Thames meanders through, making oxbows and loops. Manmade reservoirs, lakes and channels attempt to contain the water. The map shows the familiar stops on the railway line from London: Wraysbury, Sunnymeade, Datchet, Windsor, where we found a place to live. Today, princes William and Harry are helping to pile thousands of sandbags in Datchet. The weather map shows more floodwater coming.

What I remember most about Datchet is a cricket match. Our first summer in England, and we marveled that the sun did not set until about 10:00 pm. We were exploring the village one evening, and happened on the Datchet Cricket Club. Sunlight was golden across the grass, bathing the white flannels of the players and the trees surrounding the pitch in a romantic glow. Cricket is played in New Zealand, so we knew the game and appreciated its stately pace and formal rituals. The scene has stayed in our minds as the exemplar of the England we imagined when we left New Zealand.

Mousebags

For the third time since we moved to the Mendocino Coast, we’ve had an expensive car repair caused in part by mice chewing on the electrical cables. Time for another garage clean-up, and time to get serious about deterring the little darlings. We hied ourselves down to Mendocino Hardware to check out our options. Mousetraps? No. The field mice have a right to live, just not inside the building. Tony spied a gizmo that emits an ultrasonic squeal, which they’re supposed to not like. I was dubious; ultrasonic stakes installed in the vegetable garden a while back had no effect whatsoever on the gophers and voles. I picked up a can of something called Nature’s Defense. Organic, the label said. I scanned the ingredient list. Garlic, cinnamon, clove, white pepper, rosemary, thyme, peppermint. Hmmm! Interesting combination of smells. We decided it was worth a try.

On opening the can, we discovered that the smelly material was in granules that tended to clump together. The next challenge was how to contain it under the hood. I remembered that when I was a child, a favorite gift to sew for my grandma was a lavender bag. While the clipped lavender dried in the shed, I would rummage through my mother’s box of fabric scraps, drawing pieces of voile and dimity through my fingers, feeling their softness, hearing their colors sing to each other. I would stitch my neatest stitches to make a tiny bag, decorated with fragments of lace and a ribbon to draw in the top.

I figured the mice wouldn’t appreciate dimity and lace. But there was an old undershirt of Tony’s in the rag bag. I pulled out my sewing basket, threaded a needle, and set to work. Memories came flooding back as I sewed.

Filled and tied with string, the little bags are now fastened with duct tape around the engine. The car smells a bit garlicky, especially when we switch on the fan, so we’re trying to remember not to. It’s too early to tell how effective the repellant will be. I’ll let you know in a few months.

Pruning the Wisteria

I spent the morning pruning the wisteria vine that grows along our front porch. Up and down the tallest stepladder, leaning over the porch beam to reach the longest stems, I snipped and thinned. Each time I do this task, I remember with gratitude the workshop I attended years ago at the Elizabeth F. Gamble Garden in Palo Alto. “Be ruthless if you want flowers,” the instructor said. Ruthless I am. Otherwise the new growth pushes between the porch beam and ceiling, wraps itself round the lamp above the front door and seeks to enter the house itself.

Wisteria is not for the faint of heart. In May, as soon as the magnificent double purple flowers have bloomed and dropped, the new stems start growing. If left their own devices, they can reach ten feet in a year. As soon as they threaten to strangle visitors at the front door, I whack back as many as I can reach with my pole pruner. I may have to do this several times during the summer. In fall I haul out the big stepladder and take back all the foliage to somewhere near its supporting wire. However, in our mild coastal climate, the leaves don’t drop until well into the winter. It’s only then that I can see the structure I have trained over the years and can scrutinize each branch that sprouts from the main stem, looking for crossed twigs, dead wood, and stems facing back toward the house.

It’s a strenuous task. But when it is done, the prunings composted and the porch swept, there’s such a sense of satisfaction in looking up at the vine and seeing the shape of it against the house.

A Little House for Poetry

The idea came from an article in the Sept.-Oct. 2013 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine about a project to erect small installations, called poetry boxes, in public places. Their purpose, according to the artist, is to “connect people to landscape by combining poetry, visual art, and nature observation.”

The idea came from an article in the Sept.-Oct. 2013 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine about a project to erect small installations, called poetry boxes, in public places. Their purpose, according to the artist, is to “connect people to landscape by combining poetry, visual art, and nature observation.”

I decided to design a poetry box for myself. A simple little house, with just a touch of decoration: a carved spiral to symbolize the continuity of life, and a line of chevrons to signify water. I have no skill at woodwork, but my husband Tony does, and he readily agreed to take my plan and build it.

Here it is, mounted on the 6” x 6” gatepost of my fenced vegetable garden. The laminated text is thumbtacked to the back of the box, so that I can change it whenever I want to. For its debut, I placed an empty seed packet on the floor of the house and pinned up a few lines from my poem “Winter Greens,” which is published in my collection Rogue Wave at Glass Beach.

This is the gesture of hope:

to remember the taste of fresh-cut salad greens

and act on it.

This is the act of reconciliation:

muscle rhythm of shovel and wheelbarrow,

load upon load to fill the planting box.

This is the sound of faith:

a rake tamping down soil over new plantings—

snap peas, bok choi, lettuces—

tines on the diagonal, first one direction

then crisscrossed down the line.

Citizen/Science

A king tide this morning, and we’d heard that it would be useful for people to document how high the water came, so that we’d have some idea what to expect as climate change brings rises in sea level. An excellent excuse to amble down to Big River Beach in Mendocino with my new camera and practice getting my horizons horizontal.

We’ve had no major rainstorms yet this winter to wash out the sandbar that builds up at the mouth of the river. From a vantage point on the cliff, we watched the tide creep over the bar, then took the old steps down to the beach to check on the tide height at the bridge. Yes, the water was high, too high to walk on sand and touch the bridge pier, as we can usually do.

Strolling back along the tide line, we were enjoying the peace and quiet beauty of the scene when I noticed something that set my teeth on edge: a plastic dog poop bag discarded by a driftwood log. I’ve seen such offerings frequently around this region: beside a signpost, on the edge of a trail. I want to shake the humans who leave them, who are so unclear on the concept of citizenship they have no thought for the environmental mess they are causing. It’s no wonder the sea level is rising.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I plan to read this poem at tonight’s Solstice event at Gallery Bookshop in Mendocino. Obviously it was written in a year other than 2013. We’ve had no rain all month, and none in the extended forecast, so face the likelihood of a drought year. I think of this piece as a kind of prayer.

Canticle for the Winter Solstice

I honor the rain that plummets from a leaden sky

on this day when the dying sun returns to life.

I honor the wet earth where fungi lift

the smells and secrets of their darkness

into forms potent with wildness

and fallen leaves grow slimy with decay.

I honor the sudden green suffusing

the face of the sun-scorched hill,

like the blush of knowledge in a woman’s face

after her first coupling.

I honor the flame of candle and hearth

that draws to itself the breaths

of all whose lives have sometime crossed,

mingles and transmutes them into warmth

and sends them out into the rain

where they caress the tender growing tips of trees.

Texts

Searoad, a story collection by Ursula K. LeGuin, has a permanent place on my bedside table. It’s there because every now and then I need to reread a certain story. A very short story, less than three pages, it is titled “Texts,” and tells of an older woman who, bombarded by messages and calls to action, retreats to the coastal Oregon village of Klatsand for a month-long winter break. As she walks on the deserted beach, she notices that the waves have left messages in the lines of foam, messages she can almost decipher. The laciness of the foam leads her to speculate that crochet work and lace might also be legible. In a handmade lace collar she reads a message that seems directed to her: “my soul must go, my soul must go … sister, sister, light the light.” There the story ends, with the woman not knowing “what she was to do, or how she was to do it.”

I think of this oddly moving little story every time I walk on Ten Mile Beach, as I did last Sunday. The receding waves left undulating lines of bubbles, iridescent in the hazy sunlight, that popped to form patterns of foam. Scattered across the beach were strands of bull kelp, dried into coils and loops that lay like a cursive script on the sand.

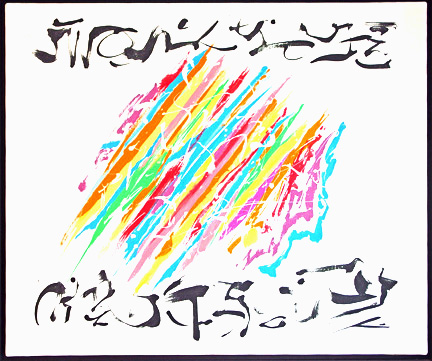

Yesterday, when the wind was brisk and the sea streaked with white caps, I remembered an interview I did for the Mendocino Art Center magazine. It was part of a series I wrote on artists who helped found the art center in the 1960s. By the time I met Jim Bertram in the early 2000s, he was senile and nonverbal, so I had to rely on material in the art center archives for information about his background and artistic vision. Nevertheless, Jim and I spent a wonderful afternoon together. I think a poem I wrote at the time sums it up:

MESSAGES

For JB

“Line expresses the inner thought. It is a narrative of what we really want to tell each other but somehow can’t seem to verbalize.”

– Jim Bertram

These bright spring days, when the wind

scribbles its white calligraphy

on a wash of aquamarine,

I think of the artist in his studio

upstairs of a weathered storefront

overlooking Mendocino Bay.

Sheet after curling sheet he showed me, canvas

after canvas, covered with calligraphic forms

that could have been words, but were not.

In our shared silence I understood his drift:

how sometimes what matters most is inarticulate:

like the line of spray from a lifting wave,

the hand of an old man painting messages of love.

On my way downstairs from Jim’s studio, I fell in love with one of his paintings, which now has a place of honor in my house. I smile when I read its message.