Summer of 1967: an immigrant’s view

San Francisco, 1967. Sunday afternoon at Maritime Park. About twenty young black men sit on a low sea wall, bongo drums between their knees, thrumming an intoxicating rhythm. A crowd has gathered. Picnicking on the beach, my husband, children and I listen too, enthralled by the joyous sound. We have spent the morning exploring the old ships at the Hyde Street pier. Later in the day we explore the new tourist attraction of Ghiradelli Square.

In a letter to parents I wrote: … an old chocolate factory now converted into an arty plaza and shopping centre with fountains, outdoor restaurants, etc. … One of the most interesting places was the Children’s Art Centre – just a little gallery for exhibitions of children’s paintings, and free paper and crayons for any infant who felt like drifting in and drawing a bit.

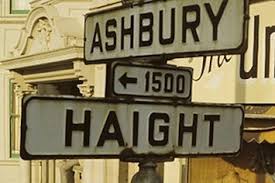

New to California, we had heard of the hippies in the Haight/Ashbury district, so on our way home to Cupertino we detoured along Haight Street. Sure enough, we passed storefronts with funky signage, long-skirted young women with hair held by braided headbands, long-haired and bearded young men in tie-dyed tee-shirts, a group playing music on a corner. Like travelers viewing exotic fauna, we gawked and drove on.

It is only now, looking back, I realize how little we understood of what we were seeing. The flower children who poured into San Francisco in what is now known as the Summer of Love were an eclectic group, revolutionary in their rejection of consumerist values, opposition to the Vietnam war, and embrace of free love, drugs, art and music. But this counterculture had a historical context, and this as immigrants we did not possess. I remember where I was when I learned in 1963 that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Like my English neighbors, I was shocked. But I did not experience that communal sharing of grief my American contemporaries remember. On British television I saw newsreel images of civil rights marchers being attacked by snarling dogs, fire hoses, and baton-wielding cops. But that was in some barbaric, far-off country. From the BBC news reports about Vietnam, it was obvious that American military involvement was a disaster, bound to fail as the French had before them. I’d not yet grasped the deadly impact of the draft on young American men.

Over the decades that followed our first summer in the US, I gradually filled in my knowledge gaps, mainly through snippets of personal information: a teacher who dodged the draft by moving to Canada, a veteran who came back from the war physically and psychologically maimed, a man who as a student registered voters in the Mississippi Freedom Summer of 1964, a doctor and his poet wife who were cast out of their New England village because of their opposition to the Vietnam war. I took part in fair housing studies, and learned first-hand the effects of racism. I read histories of the period. But there has always been for me a sense of distance, a sense of being an outsider when my contemporaries discuss the experiences of their youth. I believe this sense of distance is true of all immigrants who come to this country as adults. Try as we might to ‘become Americans,’ we simply cannot share in the memory of those collective experiences that have shaped the early lives of our American-born neighbors and friends.

However, it has been fifty years since our arrival as new immigrants, since that summer of 1967. Over the years, new national crises and issues have unfolded. We have reacted to them, talked about them with friends, shared in community actions. We learned to belong. We too have finally become part of the American story.

The rain in Camelot

When I arrived in California from England’s green and rainy land, I thought I must have landed in Camelot. Remember that song from the 1960 Lerner & Loewe musical?

The rain may never fall till after sundown

By eight, the morning fog must disappear

In short, there’s simply not a more congenial spot

For happy-ever-after-ing than here in Camelot

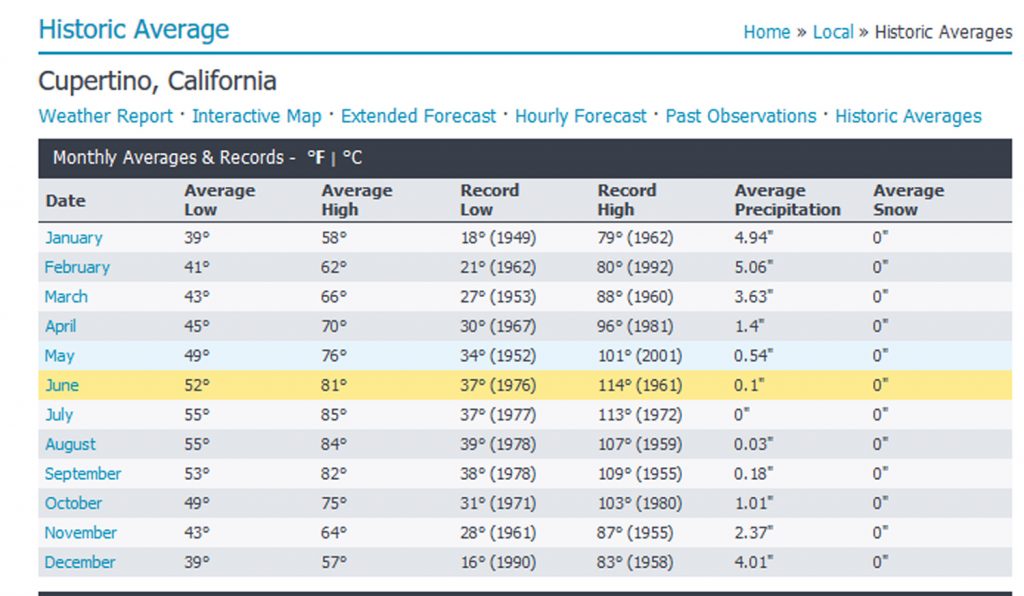

It rained for a week or two after we arrived, from late May into early June. My new neighbors kvetched, “Enough already!” After a normal rainy winter, early spring had been dry. Now the rains had started back up, and they didn’t like it. I, however, was enchanted. It truly only rained at night; the days were warm and sunny.

Eventually the rain stopped. Grass on the hills turned from green to gold. I had learned about Mediterranean climate in geography class at school: how it occurs only in five parts of the world, on the western sides of continents, between roughly 30 and 45 degrees north and south of the Equator. How it is associated with rotating high pressure zones that migrate through these sub-equatorial latitudes depending on the angle of the sun, bringing clear skies in summer and moving equator-ward to allow frontal cyclones to bring rain in winter.

A classic California landscape: Mt. Hamilton, to the east of Cupertino. Image from http://www.pleinairmuse.com/

Now I was living this rare climate. Warm sunshine day after day. Golden hills faded to a dusty tan. As summer crept toward fall, I found myself longing for the rain and dark I had hated in England. I discovered that my neighbors, too, eagerly awaited the first rain of the season. We celebrated together as the sky darkened and the first drops fell. I was learning to be a Californian.

The shapes of family

I still remember the tongue-lashing my teenage cousin and I received when we defended our widowed grandmother’s decision to file for divorce from her second husband. If the two of them couldn’t get along, we saw no reason why they should have to stay together. Mothers and aunts rounded on us. We didn’t know what we were talking about, they scolded. Grandma was a disgrace to the family. The Mother’s Union of our Anglican Church was going to throw her out, and her daughters were ashamed to show their faces in town.

Tauranga, New Zealand, was a tightly traditional little town in the 1940s and 50s, when I was growing up. Fathers worked, mothers stayed home with children. I didn’t know any single parent families. If there were divorcees, they were invisible. So were lesbians and gays.

My social environment in England was almost as sheltered. My friends were other young marrieds with small children. Our close of new row houses was filled with intact families like ours.

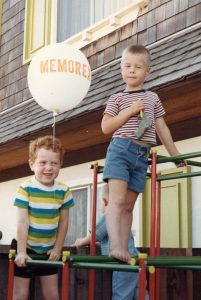

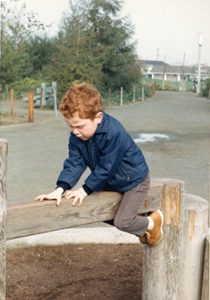

When we moved to Cupertino, CA in 1967, we lived in a complex of townhouse apartments. Each apartment had a 20 ft. by 10 ft. fenced yard. Our yard was filled with a climbing tower, a sand box, sundry tricycles, pushcarts, and other paraphernalia to keep our two small boys entertained. The neighbors helped open my eyes to other family structures: single parents, grandparents raising kids, abusive relationships.

The memory of my grandmother’s divorce comes back to me as I read a letter to my parents. After thanking them for our two-year-old’s birthday gift, I wrote:

17 Nov. 1967

Simon had a lovely little birthday party – a lunch for three little friends – after school the apartment is invaded with older kids, which would have caused problems. We seem to run a regular play centre here, what with the climbing tower and sandbox, and the new easel, with apparently unlimited supply of crayons & paper. However, the opportunities for recreation are so limited in these apartments, and so many of these kids from broken or otherwise mixed-up homes, that I guess its our contribution to the community.

There’s a self-righteousness tone to this comment, an indication of my awakening to the variety of household shapes in this new environment. A hint of defiance too. I wonder, was I getting back at my mother and aunts for their dismissal of my grandmother’s decision so many years ago?

Wide-eyed with wonder at the sights

Who can forget their first view of the Golden Gate Bridge? Or their first visit to California’s wine country. A breathlessly enthusiastic October 1967 letter to my New Zealand parents about a one-day excursion offers this immigrant’s impressions.

…We finally got away about ten, and headed north on the Nimitz Freeway, which runs up the east side of San Francisco Bay, past Oakland and Berkeley. Our destination was the Napa Valley, which is at the northern end of the bay. This is one of the most important wine growing districts of California, specialising mainly in dry wines similar to those of the Rhine Valley in Germany. A lovely day, and the air in the valley so crisp and clear – a pleasant change after the usual hazy smog of this valley. We went up through Napa itself – interesting little market town, with houses very reminiscent of New Zealand colonial architecture. We got a bit lost getting through the town, which made it more interesting – back streets are always more interesting than the usual bypass highway.

Our first stop was at Yountville – just a tiny hamlet with a huge old winery building, now disused, and converted into an art centre – fascinating little booths selling antiques, objets d’art, etc. One of the latest crazes here is digging up old bottles and other trash from the old mining towns – some of these fetching fantastic sums in such markets! We sat on the terrace of a little café nearby and had coffee and watched the vineyards and the hills. The café used to be the old Wells Fargo stage stop, now converted. We then took a side road across to the other road that runs up the valley, the Silverado Trail – very quiet and empty, and beautiful scenery. The valley is long and narrow, with mountains on either side, and vineyards covering the flat valley floor. We stopped off by a dry river bed to have our lunch, then went on to visit a winery. We chose Beaulieu, a fairly small one, where the emphasis is on quality rather than mass-production. It was rather nice, too, in that it was not at all touristised, unlike another that we stopped at later – a German one, with a replica of the family home on the Rhine – a fantastic German high Gothic mansion, entirely over-run with tourists and touristy gimmicks. By contrast, the reception and tasting room at Beaulieu was a simple stone building under plane trees, very simply and sparsely furnished with red brick floor and wooden benches. We were taken on a tour of the winery – wonderful aromatic smell of the freshly picked grapes going through the crushers, and the coolness, and row upon row of vast redwood settling tanks, some of them holding up to 20,000 gallons.

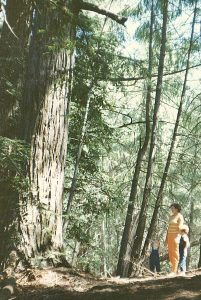

We took an interesting route home – partly because David [our four-year-old] has been breaking his neck to go over the Golden Gate Bridge. We climbed up the mountains on the west side of Napa – magnificent panoramic view of the valley floor – then dropped down the other side into Sonoma Valley at Glen Ellen, another tiny sleep hamlet, with even some original log cabin buildings. Near Glen Ellen is Jack London’s ranch, now a state park. None of us knew much about Jack London, but found it a delightful place to have a picnic tea, then walked up a little path through the trees to a revelation of a house. It was built by his widow of big fieldstones found in the grounds, as a memorial to him, and now used as a museum. From the odds scraps of manuscripts that were there I was quite impressed by his style. Probably you know more about him than we do. He died in 1916, wrote during the early 1900’s, “The Call of the Wild,” and “The Cruise of the Snark” among others. But that house was just wonderful, especially the exterior – I have never seen a place that so perfectly fitted into its surroundings.

The sun was going down as we drifted down the Sonoma – the Indian name means ‘valley of the moon’ – making the layers of hills distinct in different tones of gold. Over a few more hills into Marin County, past the gay houseboats in the artists’ colony of Sausalito, then suddenly, there was the most extraordinary view, just over the crest of a hill. Just below us the huge red towers of the Golden Gate Bridge, and across the water the skyline of downtown San Francisco, all pink and pastel in the setting sun. The huge golden sun was dropping slowly into the waters of the Pacific as we drove across the bridge, and by the time we had got through S.F. it was dark, with car headlights making thick ribbons of light on the freeway interchanges.

An arithmetical awakening

From my old black filing cabinet, a letter to my parents:

Cupertino CA, 18 August, 1967

I have enrolled for an evening class. There is a very new (actually still under construction) junior college about 5 min. drive away, so have decided to prove or disprove a long-held theory of mine that I could have done maths if I had been given the chance.

In my New Zealand high school in the 1950s, academic-streamed students were divided into two programs: languages/arts or science/maths. Since I was a girl, with strong writing skills, the choice was obvious to the decision-makers. I was given a year of basic arithmetic with some beginning algebra thrown in, and that was it. I’d struggled with long division in elementary school, and learned math tables by rote, as everyone did. In college I infuriated my math student friends by continually asking “Why?” when they tried to explain math concepts. “That’s just the rules,” I was told.

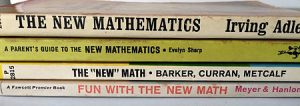

The class I took at the brand-new De Anza College in Cupertino was titled “Structure of Arithmetic”. It had a subtitle: “For Parents Who are Confused about the New Math.” New Math was a short-lived school curriculum in the 1960s that emphasized understanding the rule-systems that underlie numbers, writes Fred Martin, computer science professor at University of Massachusetts Lowell, blogging on the Computer Science Teachers Association site. He remembers it from personal experience and loved it. I learned that the decimal system is arbitrary and numbers could be expressed in any base. That was fascinating. Of course, I was the kid who learned his times tables for fun.

A Wikipedia overview notes:

Parents and teachers who opposed the New Math in the U.S. complained that the new curriculum was too far outside of students’ ordinary experience and was not worth taking time away from more traditional topics, such as arithmetic. The material also put new demands on teachers, many of whom were required to teach material they did not fully understand. Parents were concerned that they did not understand what their children were learning and could not help them with their studies. In an effort to learn the material, many parents attended their children’s classes. In the end, it was concluded that the experiment was not working, and New Math fell out of favor before the end of the decade, though it continued to be taught for years thereafter in some school districts. New Math found some later success in the form of enrichment programs for gifted students from the 1980s onward.

In a New York Times essay on the politics of math education, Carnegie Mellon historian Christopher J. Phillips writes:

Debates about learning mathematics are debates about how educated citizens should think generally. Whether it is taught as a collection of facts, as a set of problem-solving heuristics or as a model of logical deduction, learning math counts as learning to reason.

I was excited about the prospect of learning how the rules of arithmetic worked. Another motivation for taking the course was that I had a four-year-old son who was already showing signs of mathematical genius, and I knew I would soon be called upon to help him with homework. In a 2 Nov. 1967 letter I wrote:

The math course has already been useful in giving me a clearer idea of basic math concepts to help David. That child is incredible. For instance, we had a very interesting discussion at breakfast this morning on relative proportion, and I scarcely had to show him how to divide numbers into unequal proportions, e.g., 2 to 1, then subtract from each in such a way that the proportion remained the same.

I did well in the class. Receiving an A in Structure of Arithmetic was a huge boost to my self-esteem. More confident of my analytical skills, I went on to a satisfying career as a writer, editor and business systems analyst. The four-year-old grew up to be a computer science professor. I recently offered to copy edit the manuscript of his book on computational geometry. Though I didn’t have the skill to check his math, I was pleased that I could follow the logic of his argument. I even found a few typos.

In Praise of Parks

Having spent all their little lives in a place where parks had prim Keep Off The Grass signs and irate men in bowler hats with sticks enforced The Rules, my children were enchanted to discover the parks and playgrounds of their new home.

In the 1967, when we arrived in California from England, California State Parks was going through a huge expansion. Appropriations from the General Fund and a 1964 recreation bond provided well over a hundred million dollars for land acquisition and development. The government budget analysis for 1967 comments:

In the immediate future, the most pressing need of the state park system will be to provide funds for access and minimum development to enable the public to use lands now owned or currently being acquired. The existing state park system has a potential for development of about four times that of existing facilities.

With an expanding population, local governments in the Santa Clara Valley were also opening new parks and playgrounds as rapidly as they could. It was a fine time to be kids. They had their choice of playgrounds within easy driving distance: the one with the great swings, or the one with the good bars to climb on?

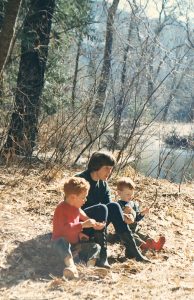

Cooking out at a forest park was one of our favorite activities. We bought a cheap little hibachi, loaded up a picnic and were off to explore.

At weekends, if the weather was hot in the valley, we might go over the Santa Cruz Mountains to the beach, remembering to take warm jackets since the fog was likely to roll in. Again choices, choices: Pescadero State Beach, or San Gregorio, or Half Moon Bay, Natural Bridges, Seacliff, Manresa…? Well before the California Coastal Act of 1976 declared that the permanent protection of the state’s natural and scenic resources is a paramount concern to present and future residents of the state and nation and that it is necessary to protect the ecological balance of the coastal zone and prevent its deterioration and destruction, the beach parks in our part of the state were already a beloved treasure.

Looking back, I recognize how innocent we were about land use politics, environmental pollution issues, climate change. Now more than ever, those parks and beaches, and the creatures living in them, need our support.

For love of a bug

A 1961 VW Beetle, the same year as mine. Image from https://vwsinportland.wordpress.com

I didn’t learn to drive until I was 29 and living in California. I had managed pretty well without a car until then. During my university years, I spent practically all my vacation time working at a fishing camp accessible only by boat. One year when I spent a week at home, my father gave me a few driving lessons. However, he lost interest when, while practicing backing in a field, I indented the shape of a tree trunk into the back bumper of his car.

Public transport worked just fine for my job in Christchurch, New Zealand, and for getting around when we lived in England. When my husband bought a Triumph Herald for his commute to work, I had twinges of conscience that I should learn to drive it. But then we’d take an excursion into London, and the huge traffic circle at Hyde Park, with its multiple lanes and multiple exits, would do me in for another six months.

Then we moved to California. One child was just four, the other eighteen months. Between our apartment and the distant shops were no sidewalks, just the weedy, lumpy verges of old orchards. I scurried to find a driving school and a babysitter. My letters to parents chronicle the story, which is probably familiar to readers who learned to drive as teenagers:

30 May, 1967

Tony has been out car-hunting tonight. He has been driving a rented Ford Mustang, & has been so pleased with it that has decided to buy one for himself. Here there is no fixed price for new cars – it’s a sort of Eastern market of haggling & bargaining, & a buyer’s market at that, so it’s a matter of going round the various dealers to see what they will offer.

18 June, 1967

I have passed the written part of my driving test. Margie Mandeville (neighbour with whom I have got very friendly) took me down to the Dept. of Motor Vehicles on Friday morning & looked after the kids in the car. Quite a good system – before you start learning to drive you have to get an instruction permit, which requires passing a written test on the Highway Code, & eyesight test. I’m a bit apprehensive about starting lessons, but guess I shall get over that.

30 June, 1967

My driving lessons are going quite well – I have an hour nearly every day, will probably take my test later next week. Very concentrated course, a bit of a strain, but am apparently managing quite well.

10 July, 1967

I am now the proud holder of a California driver’s license – passed my test this morning, with quite a good mark, considering nervous tension – 81%, passing grade is 70%. Quite a sensible system – you start off with 100 points, & get docked a set number of marks for each kind of error. Mind you, Tony passed the test the other day with 95%! Anyway, I am feeling very pleased with myself.

I am now itching to get my hands on the wheel of that Mustang – Tony has promised to let me have a go at it, provided I don’t mash it up. As I learned on a Mercury Comet, which is slightly larger, it shouldn’t be much problem. We are also going car-hunting for an elderly VW for me – they are very popular around here & have a good reputation for reliability & dealer service – this is a problem with many imported cars. What do you think, Dad, about maintenance costs on a VW of say, 1958? This is available at about $500; compared with a 1964 at about $1,000 (can’t afford anything more recent). I am really looking forward to being more mobile, & Tony is too – he finds weekend shopping a drag, when we could be swimming or sunbathing or going somewhere interesting.

20 July, 1967

I have been having fun playing with my new toy – a bright red 1961 VW. It is in very nice condition, & the engine runs beautifully – the dealer had just spent $200 on it, including a big valve job – I gather that this is the thing most likely to go wrong with these VWs. It seems your advice to go to a VW dealer is just as valid here, Dad – is it true that they are responsible for getting the car into decent running order before they sell it? We took it out & checked it for all the usual faults, could find nothing wrong but a non-functional speedo, which Tony fixed with $2 worth of cable, & talked them into throwing in a new set of tires. Tony is going to take it into an auto-probe centre next week & have it thoroughly checked out, but so far we are very happy about our $850 worth. I have had one lesson from the driving school, & managed the gear shift quite well, & now it’s just a matter of practice. I have been getting in a bit of practice on the Mustang too – just as well, as we landed up in East San Jose on Sunday, buying this car (left the kids with a babysitter) & finished up with two cars to bring home, so I was landed with the Mustang. There seemed an awful lot of car for one scared little me – much more than when I had someone with me, but quite enjoyed myself once I got over being scared.

I loved my little bug. The upholstery was torn, so I made slipcovers from brightly striped canvas. I quickly mastered the freeway system, and went everywhere I needed to go. It wasn’t until some years later, when we traded in the VW for a Mercury Montego station wagon, that I discovered some cars get more respect on the freeway than others. No longer was I being cut off by trucks, or prevented from making a lane change. Interesting, the social hierarchy of the roads.

They paved paradise

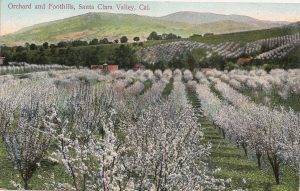

Golden fruit clings to leafy branches. Golden-skinned men climb orchard ladders, old metal harvesting pails in hand. Close to the road, a huge billboard: FOR SALE FOR COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT. The scene has stayed in my mind, my first introduction to the landscape of my new home.

I moved, with husband and children, to Cupertino, in Santa Clara County, California, in late May of 1967, just as the apricot harvest was beginning. Between our apartment, off N. Blaney Ave. by Interstate 280, and the nearest food market, on Stevens Creek Blvd., was a mile of apricot orchards. In other directions were acres of cherries, almonds and prunes. The Santa Clara Valley, a fertile alluvial plain, was until the 1960s the largest fruit production and packing region in the world. The beauty of all that spring blossom gave rise to the nickname “Valley of Heart’s Delight.”

The post-World War II economic boom and the rise of high-tech industry changed all that. My husband and I were part of a flood of new arrivals that forced out the fruit farmers and replaced orchards with tract houses, shopping centers, and business parks. It was a bittersweet time. On the one hand the energy and excitement of the new technological advances, the sense of living where the future started. On the other, sadness at the destruction of all those beautiful trees. Among my old notes I found a few lines of a poem I wrote in those early years:

The field is bare now where the orchard stood.

Apartment builders hammer at its brink.

How soon do we evict the meadowlarks

that saunter golden in the rainy dusk,

foraging through weeds by the highway’s edge?

In recent decades, with the growth of the environmental movement, there grew a collective sense that something important was being lost. Efforts were made to preserve at least the memory of that fruitful landscape. In 1994, the City of Sunnyvale preserved ten acres of Blenheim apricot trees “to celebrate the important contribution of orchards to the early development of the local economy” and created an interpretive museum beside it.

The Olson family, whose 100-acre cherry orchard was one of the last vestiges of cherry farming in the area, still retains a few acres of trees and the roadside fruit stand that began in 1899. Owner Deborah Olson commented: “We try to educate people just moving in to the area, who don’t know what it’s all about. They get a sense of place, about how it began here, and they kind of feel a part of the community.”

Blogger Lisa Prince Newman, whose family also moved to the valley in the 1960s, is collecting stories, pictures and apricot recipes from the few farming families still in the valley.

The chorus of Joni Mitchell’s song “Big Yellow Taxi,” written in the late 1960s, sums up the sense of profound loss:

Don’t it always seem to go

That you don’t know what you’ve got

Till it’s gone

They paved paradise

And put up a parking lot

Hear Joni sing “Big Yellow Taxi”

Immigrant arrival

According to archived weather records, the afternoon temperature at San Francisco Airport on Saturday May 20, 1967 hovered around seventy degrees. Fog had rolled in the previous night, but the mid-afternoon sky was clear, with visibility ten miles. As the British Airways plane dropped lower and lower over the waters of the bay, the surrounding hills became visible. Something about the quality of the light triggered a thought in my mind: this is the landscape of home.

It wasn’t the place where I grew up. Tauranga, New Zealand, is 6,500 miles southwest across the Pacific from California. But Tauranga’s distance from the equator, latitude 38 ? S, is the same as San Francisco’s to the north. The view from the air of San Francisco Bay and surrounding hills has similarities with Tauranga Harbour. Tauranga’s climate is subtropical and humid; it’s a rare day with no cloud in the sky. Even in the San Francisco Bay Area’s Mediterranean climate, with its clear summer skies, the ever-present offshore fogbank spreads a blue mistiness over the hills.

Part of the triggered thought was relief at finally coming back to terra firma. It had been a long flight, twelve hours over the pole from London. The journey had been made as comfortable as possible. The Silicon Valley company hiring my husband Tony had paid for first class tickets. The airline put us right up front, where there was plenty of legroom, and wall space to hook up a crib for our 18-month-old baby, who slept most of the way, sitting up occasionally to exclaim, “Airp’ane! Airp’ane!” The food was excellent, according to Tony. Our four-year-old son and I didn’t want to know. The two of us huddled together, miserable with airsickness.

Sight of the San Francisco Bay also signified something deeper: a recognition that this journey was the start of a new life. We were no longer in England, where the class system had us labeled as “colonials” and therefore outsiders. We were not heading back to our birth country, where the old baggage of family relationships and kiwi social assumptions would reassert their weight. We were free to find our own place in the rapidly growing, multi-cultural landscape of the exciting new high tech industry.

When we moved to England, we were unclear about how long we planned to stay. We stored boxes of belongings in New Zealand, as if we planned to return, and our mindset while we lived in England was that of visitor rather than permanent resident.

This move was different. We were immigrants, Resident Aliens in the terminology of our green cards. I knew there would be culture shock. I had experienced this phenomenon, unexpectedly, our first months in England. I had to drop all the slang I had grown up with, and was unsure how to correctly use English colloquial expressions. (Did to “go up to Oxford” mean to take the train from London or to attend the university? If the former, did one “go up” to other universities too?) This time I knew to expect that attitudes, ways of talking, and subtle social cues would be unfamiliar. Like caterpillars metamorphosing into butterflies, we would slowly take on the coloration of our new country.

When domestic and literary lives collide

Among the battered manuscript boxes in my old black filing cabinet, you won’t find the draft of my first novel. It’s gone, the victim of a long-standing conflict for women between the dream of a writing life and the urge to domesticity.

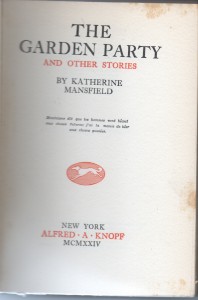

Katherine Mansfield was my heroine and role model. Born in New Zealand in 1888, she too had embarked for England as a young woman determined to make her name as a writer. Through privation and illness she continued to write and publish story collections that made her famous. I could do that too, I told myself.

But there was a variation to our respective histories I had not counted on. In New Zealand before we left, I had given birth to a stillborn daughter. Looking back, I understand that depression fueled by guilt and buried grief over this loss exacerbated the homesickness and culture shock I experienced that first year in England. My unsuccessful search for a writing job did not help. In traditional wifely fashion, I had held off until Tony found work, in a company based west of London, then scrambled, in an unforgivingly tight rental market, to find us somewhere to live nearby. By the time we were settled, a lengthy daily commute into London seemed overwhelming.

I also ran into a catch-22: even though I had been a member in good standing of the New Zealand journalists union, no paper or magazine in London would hire me unless I was a member of the British journalists union, and it was not possible to join that union without first having a job on a paper. When the local newspaper in Windsor turned me down for a posted job because I refused to promise not to get pregnant and ‘waste their time,’ I decided the best thing to do was to start work on my novel and to have another child. I believed, naively, that I could handle taking care of a child and having a writing career. In retrospect, any kind of job would have made better economic sense. We were desperately poor, but the dream of making my way as a writer still held.

I don’t remember much of the plot of that first novel. Two main characters were New Zealand immigrants to England, like ourselves. There was also another couple, and some symmetry of cross-coupling, probably influenced by the Iris Murdoch novels I was reading. I remember feeling uneasy that the plot line was uncovering a sense of dissatisfaction and disillusionment in my own life and that I didn’t know how to resolve the story.

By the time we left England five years later, my world revolved around our two small sons. I found it harder and harder to find time to work on my novel. I pushed aside the dissatisfactions with my own life that the novel echoed. In California things would be different, I told myself. I would devote my life to being a good mother. One bleak winter afternoon as we were packing up to leave the tiny house we had bought in Egham, Surrey, I came to a decision. I was alone, Tony at work, our older son playing at a neighbor’s house, the baby asleep upstairs. Outside under a lowering sky, the baby’s nappies, frozen into boards, hung motionless on the clothesline. Inside, a small coal fire burned in the grate. I sat on the floor in front of the fireplace and fed the unfinished draft of my novel page by page into the flames.

By the time we left England five years later, my world revolved around our two small sons. I found it harder and harder to find time to work on my novel. I pushed aside the dissatisfactions with my own life that the novel echoed. In California things would be different, I told myself. I would devote my life to being a good mother. One bleak winter afternoon as we were packing up to leave the tiny house we had bought in Egham, Surrey, I came to a decision. I was alone, Tony at work, our older son playing at a neighbor’s house, the baby asleep upstairs. Outside under a lowering sky, the baby’s nappies, frozen into boards, hung motionless on the clothesline. Inside, a small coal fire burned in the grate. I sat on the floor in front of the fireplace and fed the unfinished draft of my novel page by page into the flames.